Whitehall Monitor 2023: Overview

This edition of Whitehall Monitor assesses the change, performance and priorities of the civil service.

Last year was another in which much of the work of the civil service was shaped by major external events. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the energy crisis and worsening global economic outlook demanded urgent responses from the UK government.

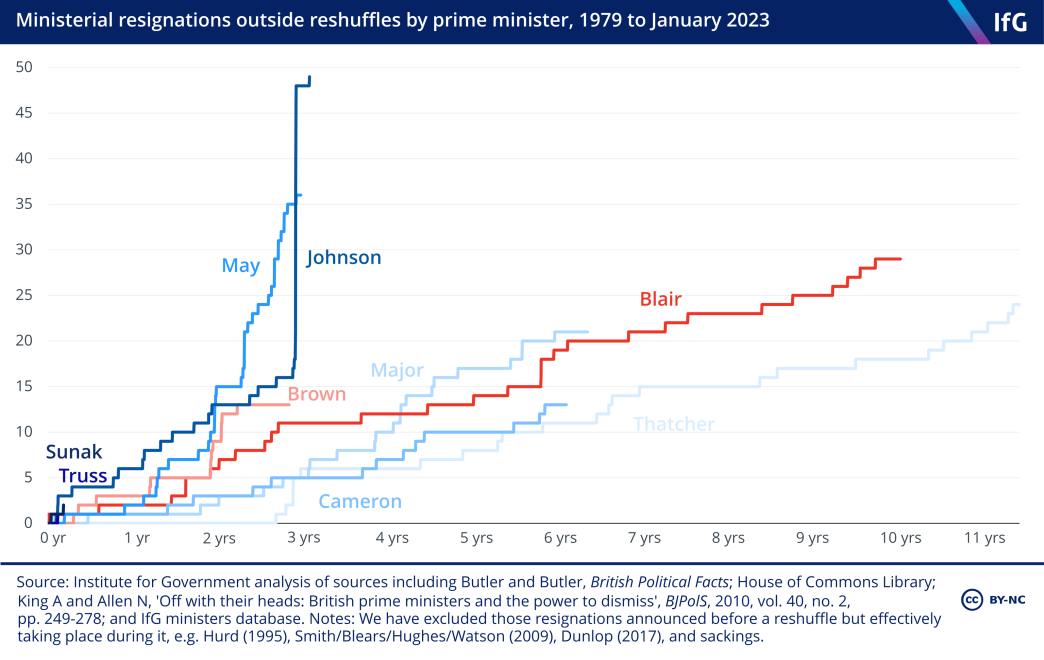

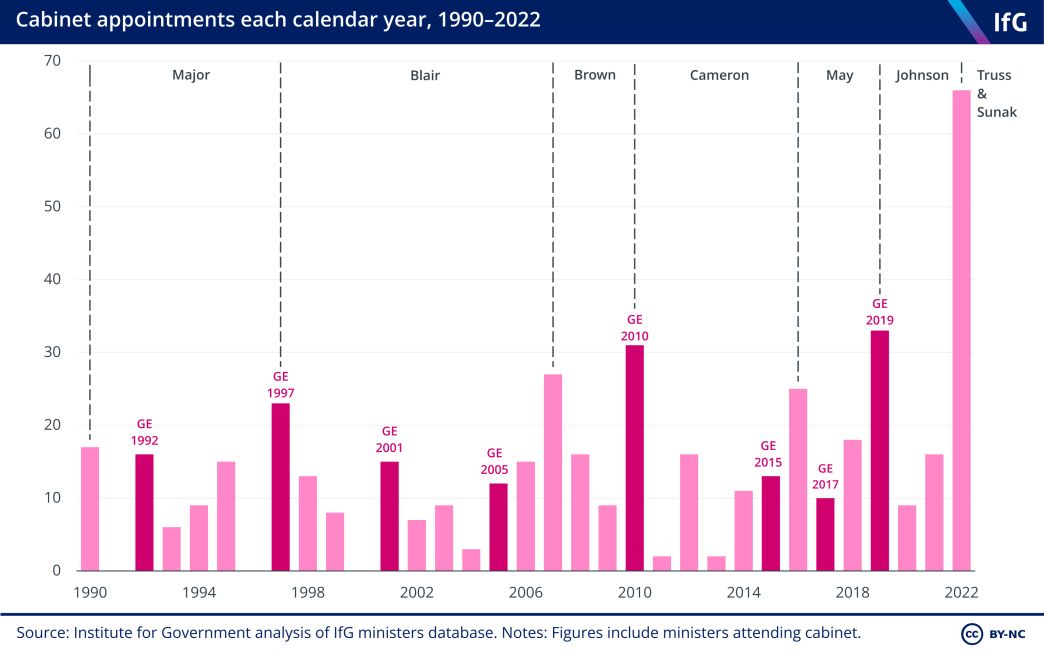

Meanwhile, domestic politics reached new levels of tumult in 2022, with three prime ministers, four chancellors and record-breaking numbers of ministerial resignations all within the calendar year.

Dealing with crises is a core part of the civil service’s role. But responses to international instability and domestic uncertainty must happen alongside work to address other, long-term problems facing the UK – of which regional inequality, low rates of housebuilding, or recruitment and retention problems in social care are just some examples. However, the political turmoil and ministerial churn of 2022 slowed decision making and jammed up policy making. Attempts to find solutions to long-term problems were delayed in favour of short-term fixes. The same was true for efforts to reform the civil service, which lost momentum and direction.

Civil service leaders face two big challenges in 2023. First will be managing the workforce. The civil service goes into 2023 with record levels of turnover, declining morale and disrupted by widespread industrial action. Much is to be done to repair the relationship between ministers and officials, still strained by unresolved disputes over pay and the workforce, hostile press briefings against civil servants and the reverberations of the ‘partygate’ scandal that erupted a year ago. Public trust in both ministers and civil servants continues to get worse.

Second, departments will need to manage increasingly tight budgets. Programme budgets, squeezed by high inflation, are set to rise very little beyond this financial year. And though the 91,000 headcount cuts target may have been dropped, administration budgets, used to staff the civil service, are still expected to be cut further. Department leads will struggle to manage these pressures through pay restraint, as this winter’s industrial action by many thousands of officials has shown. And they will have to balance cuts with the need to deliver an expanding portfolio of complex and expensive projects, while managing overstretched and in-demand public services.

Attempts to reform government, and specifically the civil service, took a back seat last year but remain critical to making government more effective in the future. Momentum needs to be revived in 2023. Civil service leaders need to safeguard the progress being made in some areas and push further in others.

In the wake of the pandemic, the civil service should make the case to be given a clearer responsibility for managing the long-term capability of government. Political turmoil is an inevitable facet of democracy, but should not be allowed to undermine the capacity of the state to address long-standing problems.

The civil service needs a greater say in managing its own capabilities – its workforce, assets and technology – across departments. And it would be beneficial for both politicians and officials for the institution to have a properly defined duty to provide high-quality, long-term policy advice to ministers.

As the next general election comes closer, the civil service should start to build a case for such long-term improvements that a refreshed Sunak government – or a new Starmer-led administration – could adopt and promote. To do this it should begin, as we do in this overview, by recognising the principal problems that have prevented government performing as well as it might in recent years: political turmoil and ministerial churn; the financial stresses of 2022 and what this means for department budgets in 2023; strained relations between officials and ministers; and inadequate clarity over the role and responsibility of the civil service.

Political turmoil and ministerial churn has made government less effective

After a November 2021 reshuffle, Boris Johnson made few changes to his ministerial team until the partygate and later Chris Pincher scandals came to a head the following summer, the latter prompting the resignation of 28 government ministers between 5 and 7 July 2022. 22 Institute for Government, ‘Ministerial resignations outside reshuffles since 1979’, retrieved 12 December 2022, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1gVHNx4kzXd947AFfQGiJg5zJrdNXrM81t2OC8UJFnw8/edit#gid=0 Johnson’s subsequent resignation was followed by a period of paralysis over the summer while the Conservative Party ran an eight-week leadership contest, eventually appointing Liz Truss his successor.

The collapse of Truss’s government just weeks later led to another change of prime minister before the end of the year, with Rishi Sunak taking over on 25 October. In her 49 days in office, Truss created further ministerial churn: appointing then replacing Kwasi Kwarteng as chancellor, after the disastrous September ‘mini budget’, and moving Suella Braverman out of the Home Office to be replaced by Grant Shapps following policy disagreements and the former’s violation of the ministerial code (Braverman would return just weeks later). This meant two of the great offices of state changed hands within a two-month premiership. 23 Doherty C, ‘Grant Shapps replaces Suella Braverman as home secretary, Civil Service World, 19 October 2022, retrieved 12 December 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/news/article/suella-braverman-resigns-home-secretary-grant-shapps-liz-truss

Sunak’s tenure as prime minister has so far managed relative ministerial stability – with the exception of Gavin Williamson’s forced resignation after a week. But three prime ministers in a year has led to extraordinary instability in the ministerial ranks. 24 Walker P, ‘Gavin Williamson resigns after chief whip messages scandal’, The Guardian, 8 November 2022, retrieved 12 December 2022, www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/nov/08/gavin-williamson-chief-whip-messages-scandal

Unsurprisingly, this political uncertainty has made the government and civil service less effective. On some issues, the Johnson, Truss and Sunak administrations held markedly different views. On others, the process of waiting for new ministers, inducting them and dealing with ministerial resignations simply meant policies were stuck in uncertainty.

The result has been policy beleaguered by delay and U-turns – including on social care, planning, onshore wind, public bodies reform and public appointments, health inequalities, local government finance, agriculture, online harms, foreign policy towards China and the EU and, lastly but importantly, civil service reform.

2022 was a year of financial stresses – in 2023 the civil service will have to manage on tighter budgets

A combination of a worsening global economic outlook and the fallout from Truss’s September 2022 ‘mini-budget’ means that a central challenge for the civil service in 2023 will be to manage increasingly tight budgets with less administrative resource.

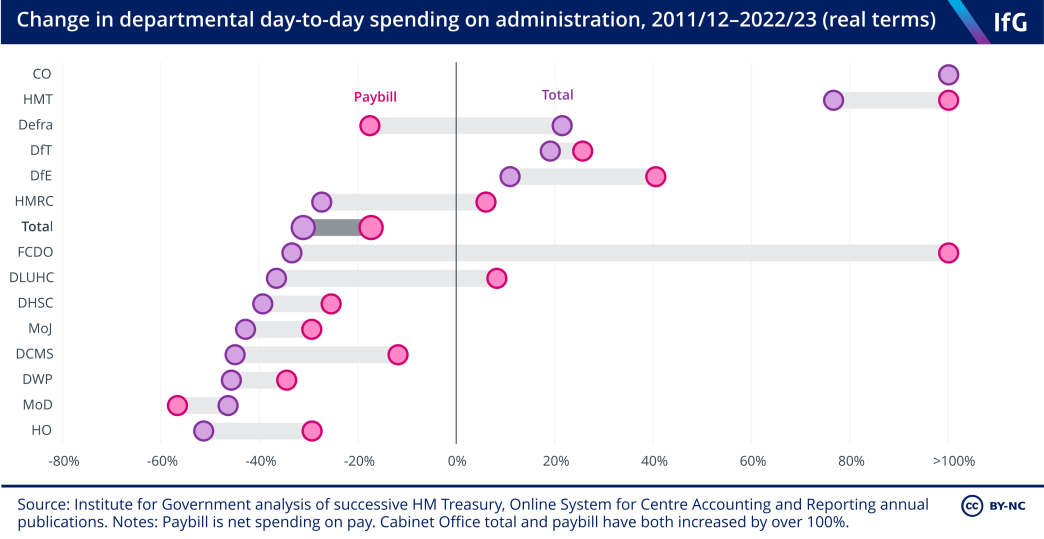

Most departments have seen their administration spending reduce by more than a fifth in the past decade. Current plans will see these budgets reduce further in 2022/23 and beyond. Departments will need to make difficult choices about how to reduce the cost of the civil service while minimising the extent to which those choices undermine the ability of government to get things done. They will need to do this against the backdrop of civil and public service dissatisfaction with pay and conditions, which led to strikes this winter and will make pay restraint a more difficult tool to deploy in search of cuts. And they will need to do this while mitigating the risks of cuts to delivering an expanding and important portfolio of major projects.

Meanwhile, for most departments, spending on programmes is set to fall or barely increase in real terms over the next few years. Meeting the public’s expectations for public services without new money will be difficult. As the resources of the civil service reduce, the problems it is tasked with managing remain. How senior officials address that tension will be an important test in 2023.

The relationship between ministers and civil servants has been strained

All of this will be made more difficult by strained relationships with ministers in 2022. Ministers, too, should concern themselves with their relationships with civil servants, because those relationships affect their ability to deliver their priorities.

Officials’ and ministers’ involvement in the ‘partygate’ scandal, more details of which came out across the year, raised serious questions about their respective standards, created negative publicity, harmed perceptions of civil service impartiality, and damaged the authority of the cabinet secretary, Simon Case. 25 Elgot J, Walker P and Stewart H, ‘Civil servants furious as Simon Case dodges sanction over Partygate’, The Guardian, 28 May 2022, retrieved 12 December 2022, www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/may/28/civil-servants-furious-as-simon-case-dodges-sanction-over-partygate

Jacob Rees-Mogg’s attempts to reform the civil service were undermined by his willingness to brief against civil servants in public. During her leadership campaign, Liz Truss similarly adopted ‘war on Whitehall’ rhetoric, which she put into practice by deciding to sack the Treasury permanent secretary, Sir Tom Scholar, striking a blow against perceived ‘Treasury orthodoxy’. 26 Scott J, ‘Liz Truss to ‘wage war’ on Whitehall waste, but Labour brands policy ‘race to bottom’ on public sector pay’, Sky News, 2 August 2022, https://news.sky.com/story/liz-truss-to-wage-war-on-whitehall-waste-but-labour-brands-policy-race-to-bottom-on-public-sector-pay-12663947

Truss and Kwarteng’s rejection of official analysis from the Office for Budget Responsibility and the Treasury ahead of the disastrous ‘mini budget’ in September undermined confidence in the UK’s fiscal credibility.

Sunak has so far adopted a different, more constructive, tone. He has dropped the headcount target for cuts and resumed the paused Civil Service Fast Stream, taking the opportunity to stress his appreciation for the work of the civil service while continuing to prioritise efficiency and value for money. 27 Nevett J, ‘Rishi Sunak: No 91,000 target for civil service job cuts’, BBC News, 1 November 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-63477209

But that does not mean his ministers’ relationships with civil servants are all in good shape. Officials in departments from across Whitehall took strike action over the winter in opposition to policy on pay and conditions. Questions surround the reappointment of Suella Braverman as home secretary just days after her resignation, and bullying allegations have forced an inquiry into the conduct of the deputy prime minister and justice secretary, Dominic Raab. Staff turnover has reached record highs following the pandemic. And the year ended with remarks from Simon Case recognising the problem of declining morale among the workforce. 28 Smith B, ‘‘The message is clear’: Cab sec acknowledges civil servants’ pay anger’, Civil Service World, 12 December 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/civil-service-pay-anger-people-survey-strikes-negotiations-union-priority

The civil service needs a long-term responsibility to steward government capability and advice

In times of political turbulence, or following unexpected events, it is more important than ever that the government makes the most of the permanent civil service, whose job should be to ensure the capabilities of government are maintained and the state can mitigate against long-term priorities being knocked off course. But it is hard to escape the view that, rather than helping to steward the government through the disruption of 2022, the civil service was at times paralysed by it.

That is why reform remains vital to improving the capability of government in the future. Now that the ministerial ranks have, at least temporarily, stabilised, Oliver Dowden and Jeremy Quin – the two ministers in the Cabinet Office responsible for reform – should re-commit to the programme of change outlined in June 2021’s Declaration on Government Reform. This will mean safeguarding progress being made in some areas, such as on relocating officials outside London, reviewing public bodies and training civil servants, but also pushing further in other areas, such as policy making, evaluation, external recruitment and interchange, and digital transformation.

But to improve the civil service’s ability to support government in future times of crisis and political instability, the civil service needs to be given a clearer responsibility to manage the long-term capability of government and the provision of long-term policy advice. Civil servants should be held accountable for undertaking that responsibility. As we have been arguing over the past year, ministers and the civil service should make the case for this stewardship function in 2023.

Report outline

This edition of Whitehall Monitor assesses the change, performance and priorities of the civil service in three parts. The first details how the civil service changed in 2022 and looks ahead to 2023. The second analyses what progress was made towards reforming government – and the civil service in particular – last year, as well as what is missing from current reform plans. The third assesses how well the civil service undertook its key roles and responsibilities in 2022, as well as ways it could improve its performance in these key areas in the future.

Part 1: The size, cost and make-up of the civil service

This part of the report analyses the ways in which the civil service changed in 2022. It identifies what these changes mean for the priorities of the civil service and the challenges it will face in 2023.

The size, structure, location and turnover of the civil service:

- slowing growth of the civil service

- record high levels of staff turnover

- stability in the structures of government departments

- changes to the number of public bodies and their employees

Budgets, spend and costs:

- the varying ways in which departments spend their budgets

- cuts to departmental administration budgets

- the rising proportion of government spending handled by public bodies

Diversity:

- the long-term trend towards a more representative civil service

- the civil service becoming simultaneously younger and more senior

- the working experience of civil servants with a disability

Skills, professions and functions:

- the continued growth of the policy profession

- the contrasting pressure on operational delivery teams

Part 2: Government reform

This part of the report analyses efforts to reform government, and the civil service in particular, last year. It identified where progress has and has not been made, where there are gaps in the government’s plans, and why the government should revive its focus on reform in 2023.

Efficiency and cuts:

- different approaches to the question of civil service headcount

- the difficulty of pay restraint in the context of industrial action and real-terms cuts

- plans to make savings from government property

- the principles of a long-term approach to efficiency

Recruitment, development and interchange:

- the Civil Service Fast Stream, its pause, resumption and prospects for reform

- progress made by the Government Skills and Curriculum Unit

- the civil service’s need to get better at external recruitment and ways it could do so

- capability-based pay

Improving diversity and inclusion:

- the risk of complacency regarding the representation of protected characteristics

- the socio-economic diversity of the workforce

- the importance of ‘inclusion’ to ‘diversity of thought’

Data and digital:

- the government’s new digital strategy

- the importance of stability in the leadership of digital reform

- progress made improving officials’ digital and data skills and on key digital priorities

- the role of legacy IT transformation in future efficiency

Public bodies and appointments reform:

- Progress made on the public bodies review programme

- Ongoing problems with public appointments

Devolution and decentralisation:

- The consequences of more English devolution and decentralisation for the civil service

- The relationship between the civil service and local government

Ministers and civil servants:

- The effect high levels of ministerial churn had on reform

- The consequences of a strained relationship between ministers and civil servants

- The case for the civil service having a long-term responsibility for government capability and high-quality advice

Part 3: Civil service effectiveness

This part of the report assesses the extent to which the civil service was effective at undertaking its key roles and responsibilities in 2022, and the ways in which it could improve its performance in the future. It includes:

Making and implementing policy:

- what 2022 showed happens when the relationship between ministers and officials at the heart of government policy making breaks down

- the need for the civil service to provide more long-term policy advice

- the case for publishing more evidence, advice and analysis

- ways in which the civil service can embed best practice methods of making policy

- next steps to improve government evaluation

Managing tight budgets:

- the pressure being applied to departmental budgets

- the importance of the government’s performance framework to making and managing difficult spending decisions

Delivering large projects:

- the growing size and cost of the government’s major project portfolio

- the risks created for major projects by squeezing departmental administration budgets

Working transparently and communicating effectively:

- declining trust in the civil service

- the role of communication in the government’s priorities in 2022 and 2023

- ongoing problems with government transparency

Leading an engaged, motivated workforce:

- problems with civil service morale

- Topic

- Civil service

- Keywords

- Civil servants Civil service reform Government reform Partygate Government transparency Government communications Cabinet

- Tracker

- Whitehall Monitor

- Publisher

- Institute for Government