Whitehall Monitor 2023 (Part 2): Government reform

This part of Whitehall Monitor 2023 analyses efforts to reform government, and the civil service in particular, last year.

Progress was made in some efforts to reform government last year, such as on the relocation of civil servants outside London, but in many areas the political turmoil of 2022 slowed down reforms and made future work uncertain. This part of the report analyses the reform work done in 2022, particularly to the civil service, looking at what was missing from current efforts, what the priorities should be for change and why the government should revive its focus on reform in 2023.

It covers attempts to reduce the cost of the civil service; progress on improving recruitment, development and interchange; the new civil service diversity and inclusion strategy; data and digital transformation; reviews of public bodies and appointments; decentralisation and devolution; and the relationship between ministers and civil servants.

Efficiency and cuts

Restrained public spending and 2022’s ‘efficiency’ drive will change how the civil service works in 2023

Responding to a deteriorating economic outlook the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, in November 2022 allowed planned borrowing to increase a little, introducing looser fiscal rules. But the downgrade to the forecast was so large that he also moved to increase taxes and cut planned spending in the medium term relative to the plans bequeathed to him by his short-tenured predecessor.

The decision to announce a big squeeze on departments’ spending beyond 2025, and only to top up plans over the next two years a little, means government departments will need to make difficult decisions over how to prioritise their spending on programmes, capital projects and administration.

The current and forecast squeeze on administration budgets in particular (already planned before autumn) means departments will need to decide how to reduce the cost of the civil service. This is having, and will continue to have, implications for the headcount of the workforce, civil service pay and the government’s estate.

Despite these pressures, Sunak was right to drop Johnson’s 91,000 headcount target

The Johnson administration’s approach to reducing the cost of the civil service centred on reducing its headcount to the size it was prior to the EU referendum in 2016 – a 91,000 job reduction.

This was an ill-conceived approach. Headcount targets lead to false economies: they encourage departments to reduce numbers through recruitment freezes and redundancies – meaning cuts come where vacancies happen to arise, rather than where would be most appropriate, creating additional cost. They can cause more talented, mobile staff to leave departments.

The target also led to ministers’ decision (since scrapped) to suspend the Civil Service Fast Stream, a move that would have cut off a valuable, and good value, stream of talent and created pressure for increased spend on external consultancies instead. 264 Clyne R, ‘Stopping the civil service fast stream is a short-sighted mistake’, blog, Institute for Government, 31 May 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/blog/civil-service-fast-stream

Setting a pre-Brexit 2016 benchmark was an arbitrary target that implied the civil service could return to resourcing the same responsibilities it held before the EU referendum. The government has changed a lot since 2016, not least because of the range of post-Brexit functions inherited from the EU. We estimate that approximately half the growth of the civil service relates to new, permanent functions the government needed to resource following Brexit.

265

Thomas A, Cutting the civil service: How best to slim down and save money, Institute for Government, 2022,

www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/cutting-civil-service

Rishi Sunak has taken a different approach since becoming prime minister. In November he confirmed in a letter to all civil servants that the 91,000 target would be dropped and the Fast Stream resumed, explaining that he did not believe “top-down targets for civil service headcount reductions are the right way” to ensure “every taxpayer pound goes as far as it possibly can”.

266

Dunton J and Markson T, ‘Civil service job-cuts target scrapped but 2% pay cap looms’, Civil Service World,

1 November 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/civil-service-91000-job-cuts-scrapped-2-

pay-cap-looms-sunak-hunt

Every department will instead be asked to “look for the most effective ways to secure value and maximise efficiency within budgets”. This will not avoid difficult budgetary decisions, but an approach that seeks genuine financial efficiency and value for money, rather than simplistic headcount reductions, is a welcome shift.

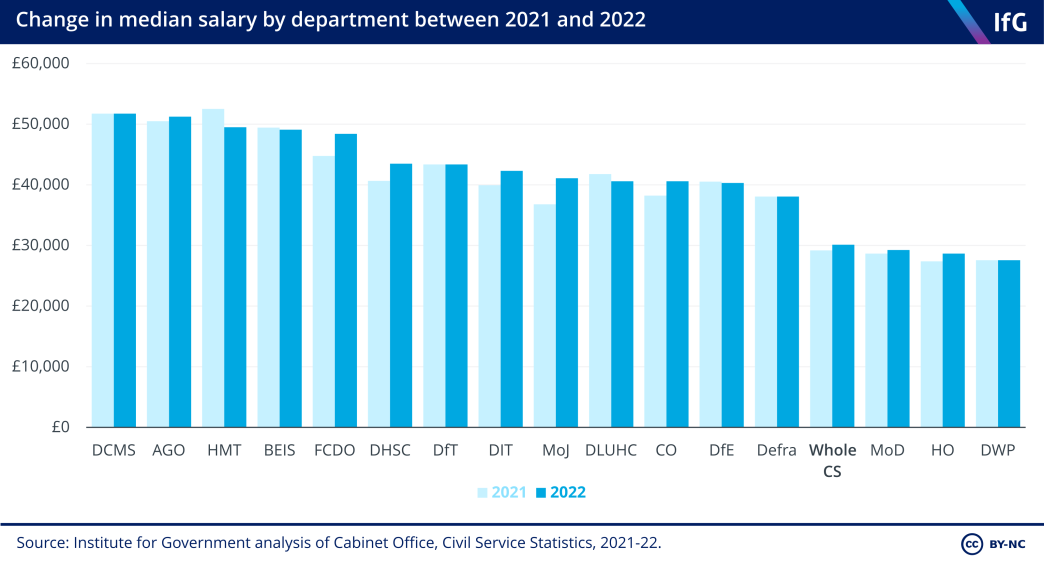

Pay at each grade has substantially decreased in real terms, posing difficult questions for 2023

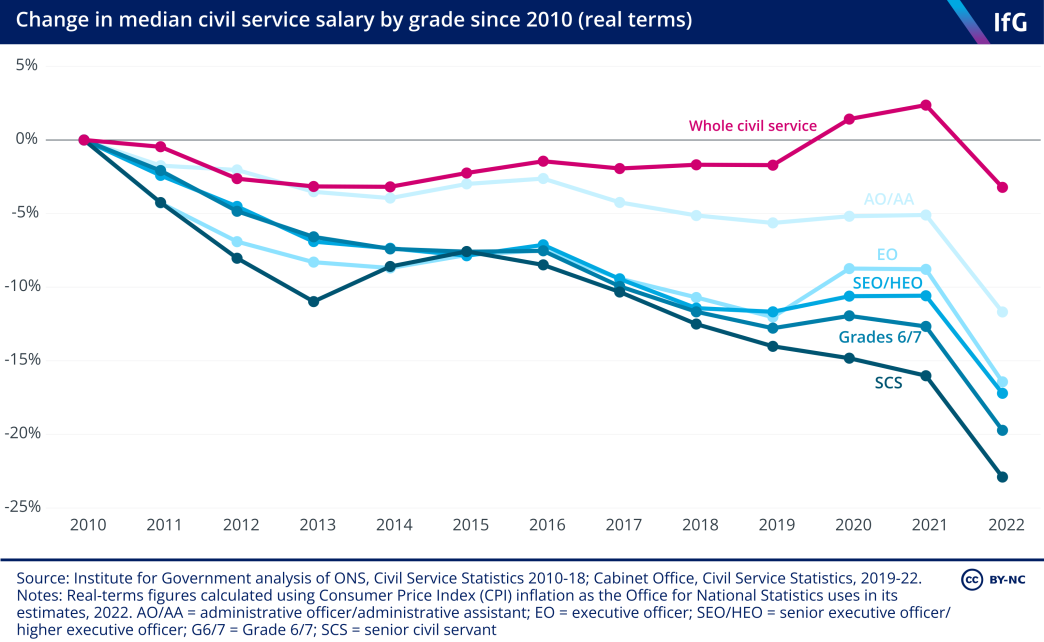

Civil servants’ median salaries at each grade have reduced in real terms by between 12% and 23% since 2010. This has consequences for the civil service’s ability to attract and retain talented officials, and affects the morale of civil servants. This worsened in 2022 as the cost of living crisis intensified.

But the overall median salary in the civil service has fallen by a much smaller 3% in real terms. The divergence between the overall median salary and the median salary at individual grades is being driven by the increased seniority of the civil service. It is likely that at least some of this is a genuine change in its composition. But it is also likely that some civil servants are being promoted to boost their salaries, to stop them from leaving the civil service and to manage morale, rather than because their skill-set and responsibilities demand it.

267

Nickson S, Thomas A, Vira S and Urban J, Pay reform for the senior civil service, Institute for Government,

9 November 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/pay-reform-senior-civil-service

This has distorted the management structure of some departments and meant that civil service pay restraint has not led to the overall savings that the government might have expected.

In 2022 civil service pay fell starkly in real terms and relative to the private sector

The current civil service pay remit guidance, covering non-senior civil servants, allows departments to make average pay awards up to only 2%.*,

268

Cabinet Office, ‘Civil Service Pay Remit guidance, 2022 to 2023’, 31 March 2022, www.gov.uk/government/ publications/civil-service-pay-remit-guidance-2022-to-2023/civil-service-pay-remit-guidance-2022-to- 2023#section4

For senior civil servants, the government rejected the Senior Salaries Review Body’s recommendation of a 3% across-the-board increase, instead announcing a 2% rise.** This increase is ungenerous even compared with other public sector workers, where most pay review bodies awarded 4–5% annual increases, and it is much lower than average pay increases in the private sector of over 6%.

269

Tetlow G and Hourston P, ‘Public sector pay and employment’, Institute for Government, 30 June 2022,

www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/explainer/public-sector-pay-and-employment

Civil servants expressed significant dissatisfaction with pay and benefits in the 2022 People Survey, which a report in The Times suggested showed only just over a quarter (28%) of officials felt their pay “adequately reflects” their performance, down from 38% in 2021.

270

Wright O, ‘Collapse in civil service morale after No 10 chaos’, The Times, 15 December 2022, www.thetimes.

co.uk/article/collapse-in-civil-service-morale-after-no-10-chaos-zwf75szj0

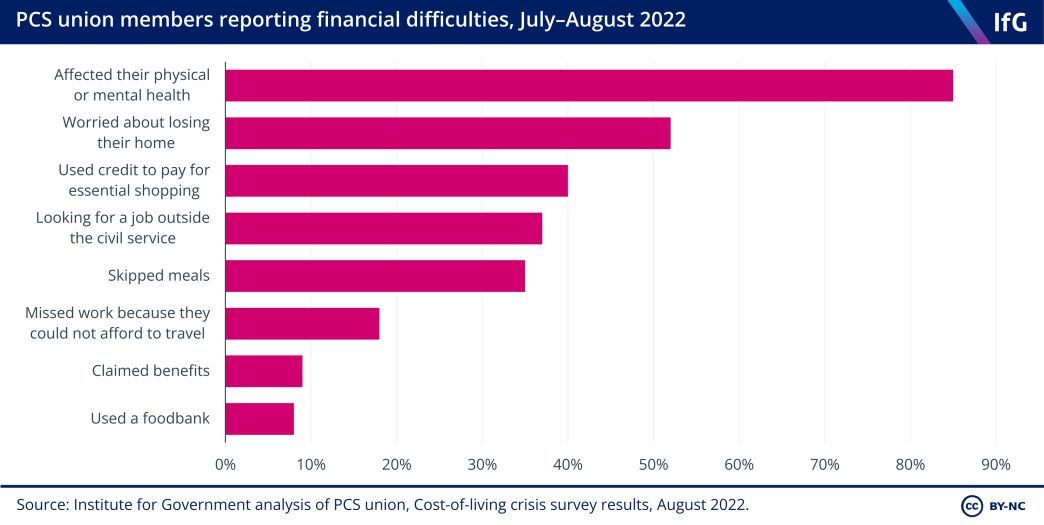

With inflation reaching more than 11% in 2022, such a large real-terms cut in civil service pay will have a serious impact on the living standards of some employees. In autumn 2022 the PCS union – the UK’s largest union representing civil servants – published evidence that among members responding to a survey about the impact of the cost-of-living crisis: 8% of respondents had used a food bank, 18% had missed work because they could not afford to travel and 35% had skipped meals.

271

‘Cost of living survey shows members’ struggles’, Public and Commercial Services Union, September 2022,

www.pcs.org.uk/campaigns/pcs-pay-campaign/cost-living-survey-shows-members-struggles

This is a problem for departments as employers with responsibility to support employees’ wellbeing. But it is a particular problem for the civil service because concern over pay during the cost-of-living crisis could fuel officials’ intention to leave the service in search of better-paid equivalent positions in the wider public or private sector, at a time when turnover is already at record highs.

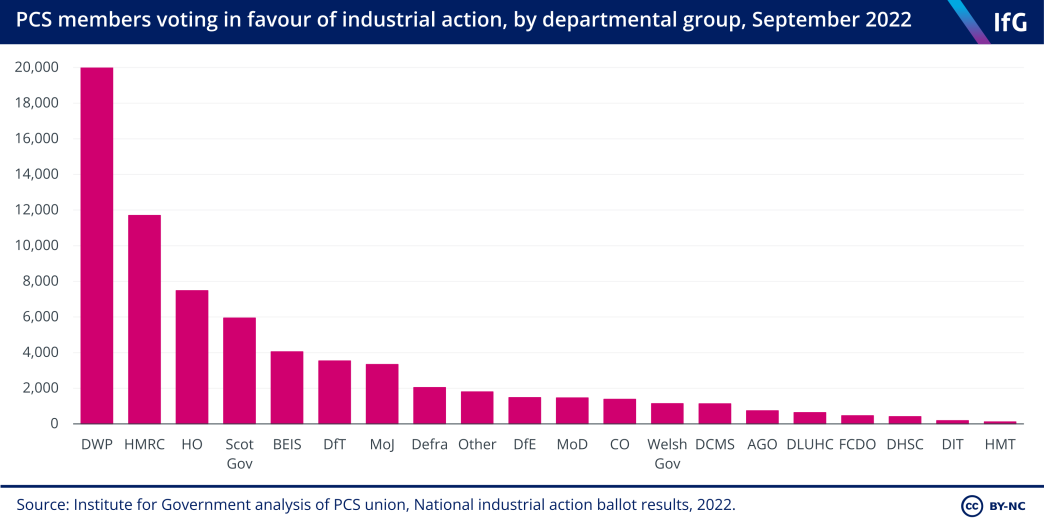

The difficulty the government will have holding down civil service pay has already been demonstrated by widespread industrial action. PCS members of at least four departments (the Home Office, DfT, Defra and DWP) went on strike in December 2022 and January 2023 over pay, pensions and conditions and a one-day all-member strike has been called for 1 February 2023. 272 Markson T, ‘Civil servants at three departments to strike from mid-December’, Civil Service World, 18 November 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/civil-servants-strike-home-office-department- transport-environment-borders-ports-december Officials on the civil service Fast Stream, who can be members of the FDA union, have voted for strike action for the first time in their history and the Prospect union intends to ballot its staff for strikes early in 2023. 273 Smith B, ‘Civil service strikes: second union moves closer to industrial action’, Civil Service World, 8 December 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/civil-service-strikes-prospect-union-ballot-industrial- action; Hughes D, ‘Cabinet Office urged to negotiate to avoid civil service fast stream strike’, Evening Standard, 17 January 2023, www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/cabinet-office-urged-to-negotiate-to-avoid-civil-service-fast- stream-strike-b1053542.html

* The 2022–23 Civil Service Pay Remit guidance notes that “departments also have additional flexibility to pay up to a further 1% where they can demonstrate targeting of the pay award to address specific priorities in their workforce and pay strategies”.

** With a further 1% to raise pay band minimums and address anomalies.

Civil service pay is not attractive enough to top talent

At the highest levels of the civil service, recent Institute for Government research has found that pay restraint has led to a decrease in the attractiveness of working as a civil servant, particularly for specialist roles – substantiating the Senior Salaries Review Body’s concern that “the government’s focus on keeping the annual pay increase low is eroding the attractiveness of the SCS proposition, which in turn will impact on the quality of those joining and remaining”. 274 Urban J and Thomas A, Opening Up: How to strengthen the civil service through external recruitment, Institute for Government, 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/civil-service-external-recruitment The senior civil service has faced the biggest real-terms pay cuts of any grade since 2010. This cannot be as readily mitigated by over-promotion to secure higher pay for directors, directors general and permanent secretaries – as it can at lower grades – because there are many fewer roles available at the most senior ranks of the civil service.

One recent example of the impact of uncompetitive pay at the top of the civil service was the government’s three-year hunt to recruit a chief digital officer, which concluded in July 2022. The civil service chief operating officer, Alex Chisholm, told the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee that while the proposed salary was “top whack” for the civil service, market research showed that “the sort of people we are looking for would be earning multiples of what we are able to pay” outside government. 275 House of Commons Public Accounts Committee, ‘Oral evidence: Specialist skills in the Civil Service’, HC 686, 2 November 2020, retrieved 22 November 2022, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/1207/ default, Q81.

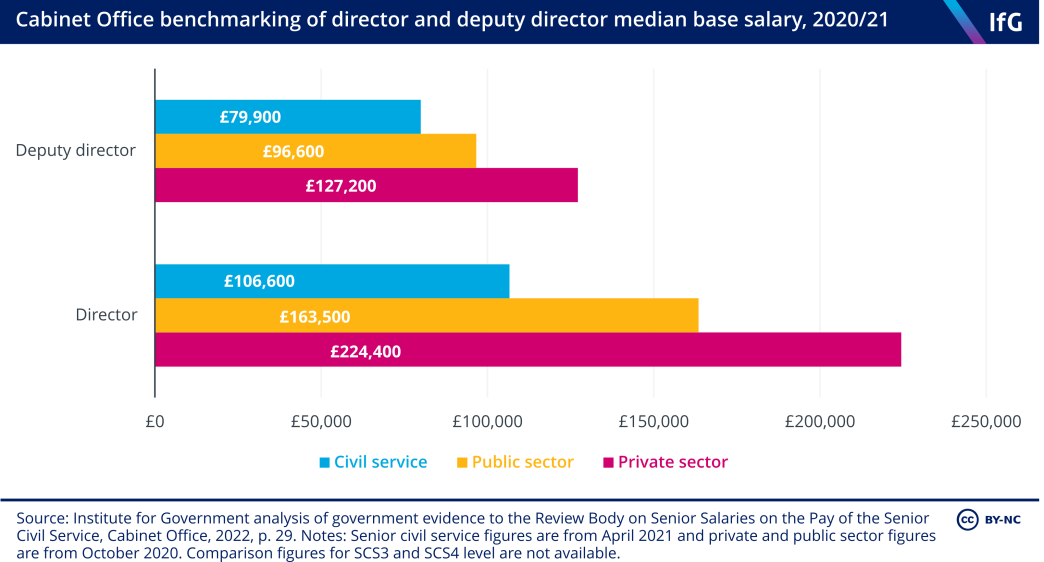

Cabinet Office benchmarking has found that the median director-level civil servant’s base salary is less than half of their private sector equivalent and only 63% of an equivalent in the wider public sector. This does not account for the relatively generous civil service pensions, but it also does not account for other benefits and payments that are larger in the private sector, from private health care and gym memberships to cash bonuses. At the highest levels, the median permanent secretary earns approximately 10% of the median FTSE 250 CEO.

276

Speke A, Window H and Hildyard L, Analysis of UK CEI Pay in 2021: High Pay Centre and TUC, 2022,

https://highpaycentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CEO-pay-report-2022-1.pdf

,

277

Review Body on Senior Salaries, Forty-Fourth Annual Report on Senior Salaries 2022 (Report no. 94), CP 727, The Stationery Office, July 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/ uploads/attachment_data/file/1092289/SSRB_44th_AR2022_accessible.pdf; table 3.2

Civil service salaries are unlikely to ever be able to compete directly with the private sector, especially at the top levels. But the size of the pay gap is a problem. Ministers need to be aware that continuing to hold down civil service pay in an attempt to save on administration budgets will worsen existing difficulties with the external recruitment and retention of the best talent – particularly of people with in-demand skills who could command much higher salaries outside the civil service. This runs contrary to their stated aim to make the civil service more ‘porous’ and “encourage entrants with specific, high demand skills”, and will have a negative impact on the efficiency and effectiveness of government. 278 Cabinet Office, Declaration on Government Reform, 15 June 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/ declaration-on-government-reform/declaration-on-government-reform

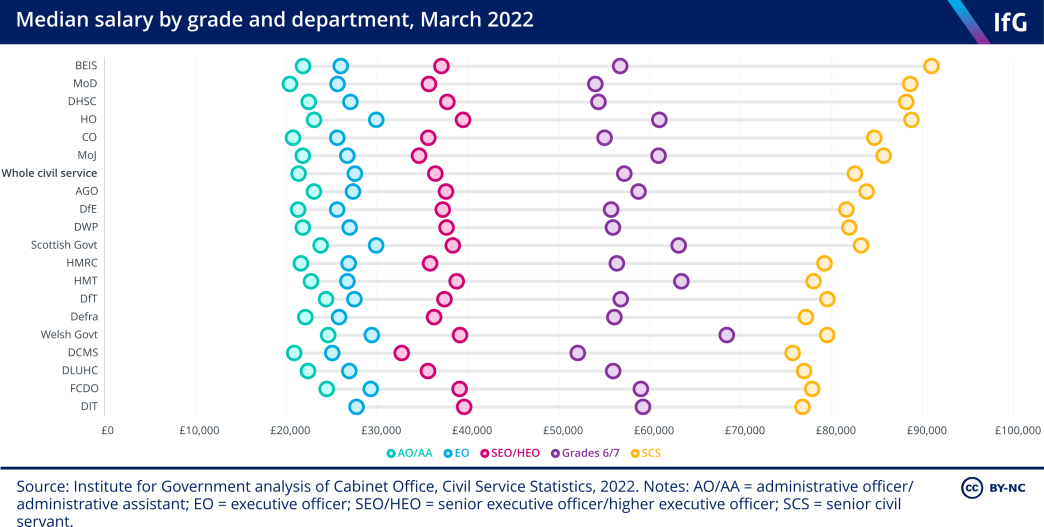

There continue to be differences in departments’ pay offers

Across Whitehall there remain differences between salaries at the same grade in different departments. This is a consequence of the government’s departmental structure and, to an extent, allows departments some flexibility to set pay to attract and retain talent. However, it also helps to drive the churn of staff at grade 6 and below, who are able – indeed incentivised – to ‘job hop’ in search of better salaries.

DCMS* is the department with the highest median salary, while the Treasury, which occupied that spot last year, has fallen to third. The departments with median salaries below the civil service median remain the MoD, Home Office and DWP – three large, operationally focused departments. Departments’ relative rank on this metric is largely determined by their grade structure. For example, the Treasury’s reputation is of a department with relatively low salaries, but it is ranked highly here because it is a disproportionately senior department, meaning the median staff member is of a higher grade (and therefore entitled to a higher salary) than in most other departments.

* A list of departmental initialisms is found in the Methodology of this report.

The government continues to seek savings from its property

The government estate is a further source of savings. In August 2022, the publication of the Government Property Strategy 279 Government Property Function, ‘Government Property Strategy 2022–2030’, 29 August 2022, www.gov.uk/ government/publications/government-property-strategy-2022-2030 showed that the size of the “central general purpose estate” had reduced by 30% since 2010, delivering annual running cost savings of £1.6 billion. Some £5.2bn was generated by property disposals between April 2015 and March 2020, with the number of central London offices, for instance, falling from 63 to 36 between 2018 and the strategy’s publication in 2022. This has had benefits beyond cost savings. The government says it had reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 57% in 2020/21 compared to 2009/10, with an estimated 38% of this due to improved management of the estate.

In terms of further cost savings, the strategy commits to cut £500 million in operating costs from the estate by 2025, as well as developing a pipeline of property disposals aiming to generate £500m in capital receipts each year. But there are too few details as to how either target will be achieved. In December 2022, the Public Accounts Committee described the operating costs target as “not sufficiently ambitious”,

280

House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, Managing central government property: Thirty-First Report of Session 2022–23, HC 48, 21 December 2022, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/33303/

documents/182733/default, p. 7.

noting that it represents roughly a 2% reduction. It also casts doubt on the feasibility of the property disposals target, noting that departments have previously been falling short of their targets on land disposals, and suggested that “recent market turbulence may also negatively impact the programme”.

281

House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, Managing central government property: Thirty-First Report of Session 2022–23, HC 48, 21 December 2022, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/33303/

documents/182733/default, p. 6

These are valid concerns – particularly around property disposals – to which the government should provide substantive responses.

Beyond property disposals, the government can also use office space more cost- effectively through greater co-location of teams and departments – which can boost performance by breaking down departmental siloes, as the Institute for Government research into the Darlington Economic Campus has found.

282

House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Written evidence from the Institute for Government to the ‘Planning for the future of the Government’s estates’, 10 January 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/114639/pdf

This is the purpose of the Government Hubs programme, which co-locates teams from different government departments in the same office, aiming to achieve “value for money for the tax-payer and creating a modern, flexible estate, facilitating smarter working for civil servants”.

283

House of Commons, Hansard, ‘Written questions’, 30 September 2019, https://questions-statements. parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2019-09-25/291132

The first phase of the programme has been completed, with HMRC delivering 14 hubs across the UK.

284

House of Commons, Hansard, ‘Written questions’, 8 December 2022, https://hansard.parliament.uk/ commons/2022-12-08/debates/D7736228-B576-4A8F-9C85-B67973F0D4C5/GovernmentHubs

The government says that through this greater efficiency of space, the department is on track to deliver around £300m of savings up to 2025.

285

Government Property Function, ‘Government Property Strategy 2022–2030’, 29 August 2022, www.gov.uk/

government/publications/government-property-strategy-2022-2030, p. 6.

Phase 2 of the programme, led by the Government Property Agency, is currently under way.

286

House of Commons, Hansard, ‘Written questions’, 8 December 2022, https://hansard.parliament.uk/ commons/2022-12-08/debates/D7736228-B576-4A8F-9C85-B67973F0D4C5/GovernmentHubs

The Government Property Strategy states that the programme is set to deliver up to 50 additional hubs by 2030.

287

Government Property Function, ‘Government Property Strategy 2022-2030’, 29 August 2022, www.gov.uk/

government/publications/government-property-strategy-2022-2030, p. 10.

As the government seeks to identify further efficiencies, reduce its office footprint and increase cross-departmental collaboration, it should also consider the impact of changing working practices since the pandemic. It is surprising that the Government Property Strategy does not acknowledge the impact that dramatically changed post- pandemic patterns of working will have on the way the government estate is used, nor set out plans to make strategic changes in response to this.

The government should take a long-term approach to efficiency

Real savings from administration budgets in the civil service can only be small in the context of wider public spending – the whole civil service pay bill is around 1% of total government spending. 288 HM Treasury, Public Expenditure: Statistical Analyses 2022, CP 735, The Stationery Office, 2022. And ministers will need to be clear, and make clear, that there are few fast, easy ‘efficiencies’ to be saved from the civil service. Cuts will mean the government not doing work it might otherwise have done.

But the civil service should not be immune to spending restraint and it should always aim to become more efficient. Sunak’s more constructive tone on civil service efficiency is welcome, and it is right that he has asked departments to target ‘pounds’ – in the form of actual budget savings – not ‘people’ in terms of headcount alone. But there are further steps he and his ministers should take to achieve genuine civil service efficiencies and make cuts with minimum damage to the government’s capabilities.

First, any cuts should be made over a long-term time frame. Few efficiencies are achievable in the short term. Instead ministers and senior officials should identify the workforce the government will need over the next five, 10 and 15 years rather than the next two to three. This will require the government to identify the skills it will need more and less of in years to come, to translate this into departments’ workforce plans and recruitment policies. Doing so will help to avoid the ‘boom-and-bust’ cycle of civil service expansion and retrenchment that has prevailed in recent decades.

Second, ministers should be prepared to invest to save. The most valuable savings require up-front spending. This is particularly true for digital investments, such as efforts to replace legacy IT infrastructure and create the GOV.UK One Login system,* which have potential to improve service provision, minimise duplication and enable officials to be reallocated to other tasks. Another example is the asylum system – improvements to speed up decision making will require up-front investment, but stand to save public spending elsewhere, such as on hotel accommodation for individuals awaiting decisions.

Without a long-term plan for efficiency and workforce management, the civil service risks another period of staffing retrenchment without the strategic decisions necessary to avoid additional costs and risks.

* A single sign-in system that would allow users of GOV.UK services to log in with a single email address, password and two-factor authentication, reducing the need to keep separate records for different government services.

Recruitment, development and interchange

It was right to resume the Fast Stream – now it should be improved

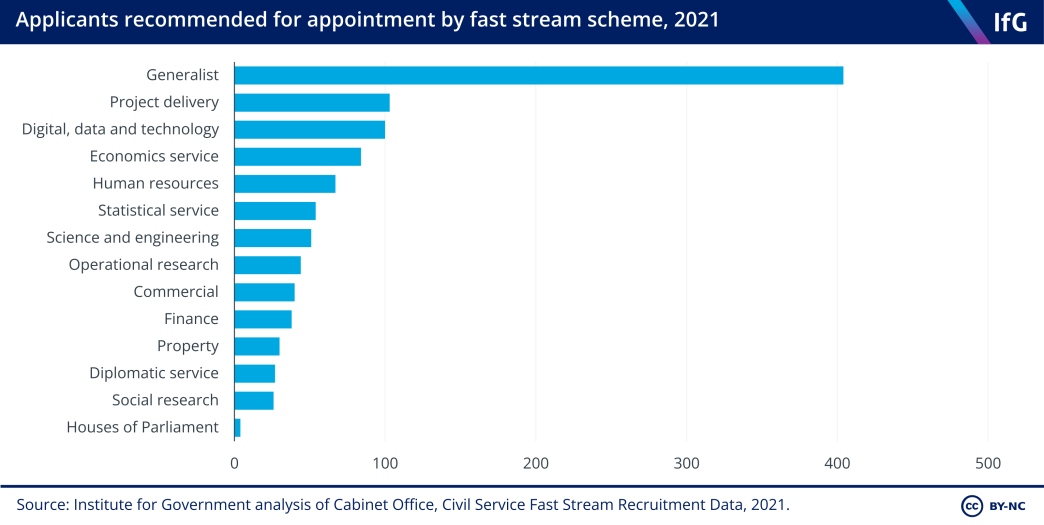

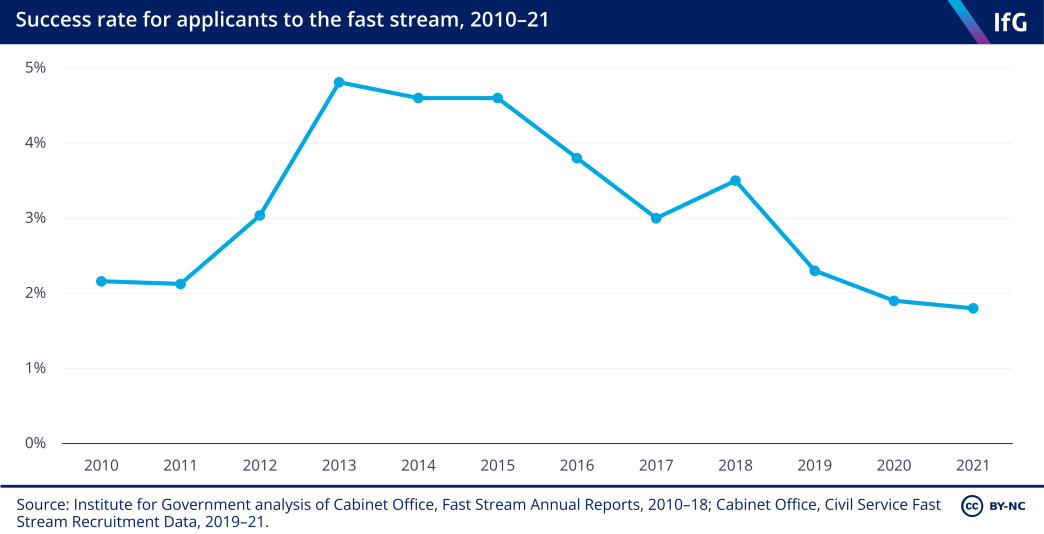

In May 2022 the Johnson administration announced it would pause recruitment to the Civil Service Fast Stream for at least one year, as part of efforts to meet the 91,000 headcount reduction target. 344 McGarvey E, ‘Civil service pauses fast-track graduate scheme to cut off staff numbers’, BBC News, 31 May 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-61641930 Later in the year, after becoming prime minister, Rishi Sunak reversed this decision and resumed the Fast Stream without a year’s recruitment being missed. Around 1,000 graduates are recruited on to the 16 ‘streams’ across the civil service each year, at a cost of approximately £41m. 345 Civil Service Fast Stream home page, GOV.UK, (no date), www.faststream.gov.uk; Clyne R, ‘Stopping the civil service fast stream is a short-sighted mistake’, blog, Institute for Government, 31 May 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/blog/civil-service-fast-stream The ‘generalist’ stream across departments is the biggest, taking in 38% of graduates in 2021. 346 Cabinet Office, ‘Civil Service Fast Stream: recruitment data 2019, 2020 and 2021’, GOV.UK, 10 December 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-fast-stream-recruitment-data-2019-2020-and-2021 Other streams focus on high-priority technical areas such as project delivery, data and economics.

While the Fast Stream can be improved, it is an asset to government. It is a highly competitive scheme, with a successful application rate of less than 2% in 2021, and has been named The Times’ top graduate employer for the last four years in a row. 347 The Times Top 100 Graduate Employers, 2022-23, www.top100graduateemployers.com Suspending the Fast Stream was a mistake and a good example of the false economies created by headcount targets.

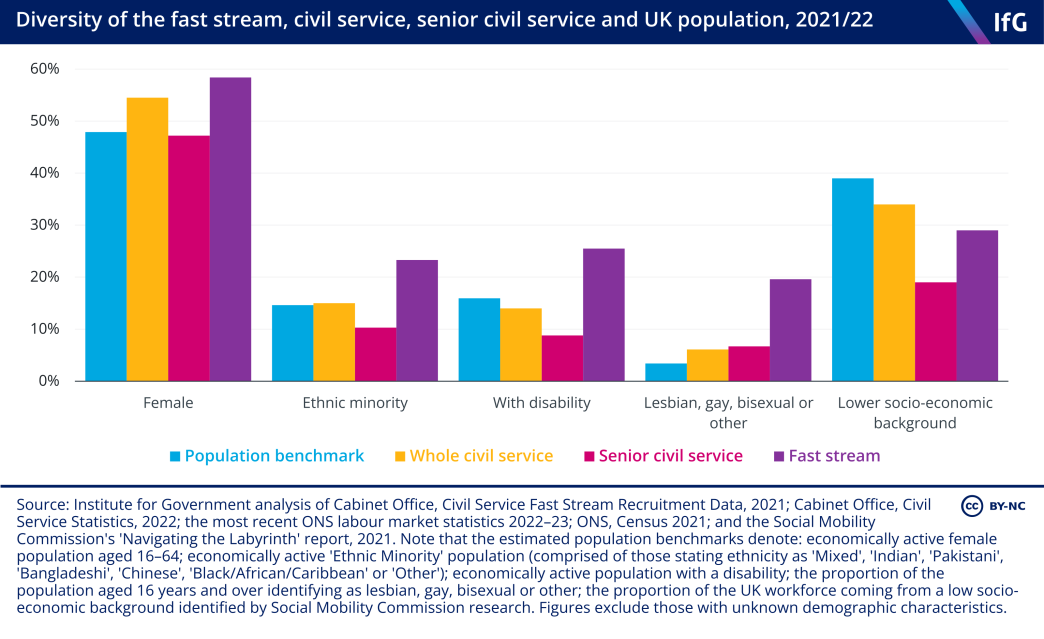

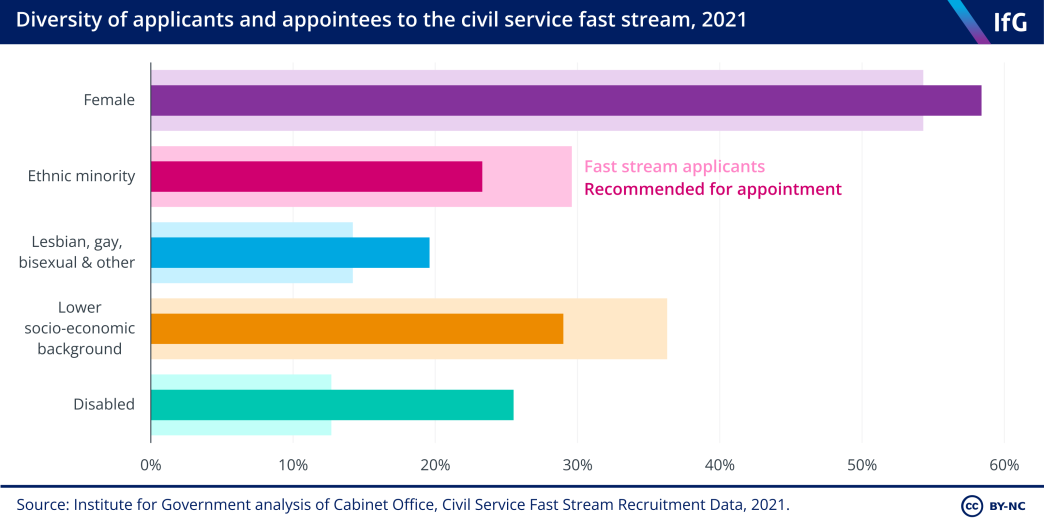

The Fast Stream is also an effective tool the civil service has used in recent years to make its workforce more representative of British society, to help bring fresh perspectives into departments and policy making. The scheme is at least as, or more than, representative of the working population on the grounds of sex, ethnicity, disability and sexual orientation. It also outperforms the wider civil service and senior civil service on these characteristics. However, the scheme continues to under- represent people from low socio-economic backgrounds, making up just 29% of Fast Streamers compared to 39% of the UK workforce.

Sunak’s decision to cancel the planned suspension of the Fast Stream will allow ministers and officials to focus on improving the programme. Progress has been made over the past decade; for example, with the introduction of dedicated, technical schemes in high-priority areas such as digital, data and technology, commercial and project delivery.

The Government Skills and Curriculum Unit (GSCU) has now been tasked with making further improvements. Recent work has included broadening outreach across universities and targeting STEM subject backgrounds in outreach, introducing a new STEM generalist stream, piloting new data and digital skills provision for graduates on the generalist scheme and a plan to change the management arrangements for new graduates. But there remains further to go.

The Fast Stream still struggles with a legacy dominated by white, middle-class Oxbridge graduates. In 2021 Oxbridge applicants to the scheme had a success rate of 2.8%, a full percentage point up on the overall success rate of 1.8%. 348 Cabinet Office, ‘Civil Service Fast Stream: recruitment data 2019, 2020 and 2021’, GOV.UK, 10 December 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-fast-stream-recruitment-data-2019-2020-and-2021 The scheme also under-represents people from lower socio-economic backgrounds.* The success rate for minority ethnic candidates, at 1.4%, was by contrast lower than both the average and the 2.1% for white applicants. Tackling these problems in recruitment should be a priority for the scheme.

The biggest stream by some margin remains the ‘generalist’ programme. This continues to incentivise generalist policy careers with rapid turnover between roles, at the expense of the accumulation of deeper subject matter expertise and operational experience. Recent Institute for Government research analysed this trend as a problem for policy making across the civil service and recommended ways in which it could be addressed, including by encouraging officials to ‘anchor’ policy careers in areas of specialisation.

349

Sasse T and Thomas A, Better policy making, Institute for Government, 3 March 2022,

www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/better-policy-making

Reflecting this in the Fast Stream and ensuring graduates undertake more operational placements would be a good next step. Plans to support generalist Fast Streamers to anchor their placements in climate policy are a welcome step in the right direction.

350

Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener, last updated

5 April 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/net-zero-strategy, p. 259.

The government also intends to increase the exchange of knowledge and talent between the civil service, other sectors and other parts of the public sector. 351 Cabinet Office, Declaration on Government Reform, 15 June 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/ declaration-on-government-reform/declaration-on-government-reform Doing so would help to improve the often poor working relationships between Whitehall and other parts of the state, in particular local government. 352 Thomas A and Clyne R, Responding to shocks: 10 lessons for government, Institute for Government, 23 March 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/responding-shocks-government This could be an opportunity for the Fast Stream and mutually beneficial with equivalent schemes. There are many other successful graduate schemes across the public sector, including the Local Government Association’s National Graduate Development Programme and the NHS Graduate Management Training Scheme.

As part of efforts to reform the Fast Stream, the GSCU should work with their counterparts in other parts of the public sector to develop a cross-public sector option between the Fast Stream and its public and social sector equivalents. Giving some graduates the chance to experience public service in local government, the NHS and other settings, as well as the civil service, would improve understanding between layers of government. It would have a lasting impact as those graduates develop their careers with a broader experience of public service.

* Applicants from ‘intermediate’ and ‘routine and manual’ socio-economic backgrounds had a success rate lower than the average (1.8%) and those from ‘higher managerial, administrative and professional’ backgrounds (2.1%), at 1.5% and 1.3% respectively.

The Government Skills and Curriculum Unit has real potential to improve training and development in the civil service

A high-quality training offer is essential if the civil service is to recruit and retain talented staff, while giving existing civil servants opportunities to develop. The GSCU was established to this end in 2020, as a ‘one-stop shop’ for all training in the civil service, including an induction for new civil servants and leadership programmes. The unit set out a new curriculum, launched online courses, and began piloting an online induction course and data masterclass for senior civil servants.

353

Lilly A, Clyne R, Thomas A and others, Whitehall Monitor 2022, Institute for Government, 2022,

www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/whitehall-monitor-2022, p. 67.

The GSCU continued to make progress in 2022. More than 10,000 new civil servants have now completed the online induction, recently fully launched. The unit established the Leadership College for Government in April 2022, with a prospectus following in June, and has tested a foundation management programme with five early adopter cohorts. It led the development of a new apprenticeship strategy. The unit is also responsible for the College for National Security, announced by the government in March 2022, and has secured seed funding for the college as it prepares a business case for later in 2023. The development of civil service-wide Campus Online, a new digital learning platform to replace existing, unpopular services, continues.

While this is overall a positive picture, building skills in the civil service is a long-term aim and has not yet been realised. It may not yet have been recognised by civil servants themselves: the 2021 Civil Service People Survey 354 Cabinet Office, ‘Civil Service People Survey: 2021 results’, 28 April 2022, www.gov.uk/government/ publications/civil-service-people-survey-2021-results [benchmark scores dataset, table 1]. showed no substantial increase in civil servants’ satisfaction with their learning and development opportunities since the unit was created.* And while the unit’s induction package is undoubtedly useful, it amounts to roughly six hours of online content.

The Institute has previously argued that the government should set its sights higher, particularly for new senior hires, and follow through on the recommendation of the Baxendale report

355

Civil Service, ‘Baxendale Report: How to best attract, induct and retain talent recruited into the Senior Civil

Service’, 27 March 2015, www.gov.uk/government/publications/baxendale-report-how-to-best-attract-induct-

and-retain-talent-recruited-into-the-senior-civil-service, p. 19.

(an independent report commissioned into how to attract, induct and retain talent into the senior civil service) to develop a standard five- to ten-day induction that all senior external hires attend.

It is also important the unit’s progress is treated as a positive start from which to build. Departments must make comprehensive use of the resources created, ensuring staff engage with them and managers understand professional development of their teams is an indispensable part of their role. Only by leading this kind of culture change more broadly across the civil service will the GSCU achieve the objectives for which it aims.

There are also risks to the future of the GSCU. Its headcount has already been reduced, raising concerns over whether it has the resources it needs to deliver its commitments, including its plans for the Fast Stream. As elsewhere funding pressures are a concern: in the recent autumn statement, Cabinet Office RDEL was scheduled to fall (excluding depreciation) from £700m in 2022/23 to £400m in 2024/25;

356

HM Treasury, ‘Autumn Statement 2022: documents’, 17 November 2022, www.gov.uk/government/

publications/autumn-statement-2022-documents, p. 20.

the impact on the unit’s funding allocation is not clear. If the civil service is to attract and retain the staff it needs, the GSCU needs stable and adequate resources.

* In the 2021 survey, across four questions related to learning and development, two questions saw an increase in the proportion of respondents expressing agreement or strong agreement with a positive proposition, compared to 2020. These proportions increased from 65.8% to 67.1%, and from 51.8% to 53.6%. Two questions saw a decrease – from 51.5% to 49.7%, and from 51.9% to 51.4%.

The civil service must get better at external recruitment

The government has said that it wants to bring in more external talent. June 2021’s Declaration on Government Reform contained specific actions to “establish new, appropriately and consistently managed, entry routes for professionals from outside government” and “encourage entrants with specific, high demand skills”. 357 Cabinet Office, Declaration on Government Reform, 15 June 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/ declaration-on-government-reform/declaration-on-government-reform The cabinet secretary, Simon Case, wrote in November 2021 that the government was intent on “bringing in more outside expertise from business, industry and academia”, a call he reiterated in an interview with Civil Service World in December 2022. 358 ‘Simon Case: “The thing I found most difficult in 2022? Telling the PM the Queen had died”’, Civil Service World, 12 December 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/in-depth/article/simon-case-hardest-2022-queen-died- telling-prime-minister-csw-perm-sec-roundup-2022 And the government strengthened its policy of advertising all senior civil service jobs externally by default in May 2022. 359 Cabinet Office, “All Senior Civil Service jobs to be advertised externally from today”, GOV.UK, 13 May 2022, www.gov.uk/government/news/all-senior-civil-service-jobs-to-be-advertised-externally-from-today

However, little progress has been made. The number of senior civil servants recruited externally in fact fell from 20% in 2019/20 to 18% in 2020/21. 360 Senior Salaries Review Body, Senior Salaries Review Body Report: 2022, 19 July 2022, www.gov.uk/government/ publications/senior-salaries-review-body-report-2022 And inward secondments still prove difficult to organise on an individual basis, let alone at scale, despite the government’s target that 2% of roles at grade 7 and above should be either on secondment or filled by a secondee by 2023.*

The civil service is particularly poor at bringing in specialists, especially into senior roles. More external recruitment of specialists would be especially beneficial for two main reasons. First, it would increase the technical expertise available to the civil service, making it better equipped to deliver ministers’ priorities. Second, as a result of hiring people with different professional experiences who have been trained to approach problems in different ways, it would increase the cognitive diversity of the civil service. A convincing body of research suggests that would improve the way it identifies problems and operationalises solutions. 361 Page S, The Difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools and societies – new edition, Princeton University Press, 2008; Page S, The Diversity Bonus: How Great Teams Pay Off in the Knowledge Economy, Princeton University Press, 2019; Mangelsdorf ME, ‘The trouble with homogeneous teams’, MIT Sloan Management Review, 2018, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 43–47; Reynolds A and Lewis D, ‘Teams Solve Problems Faster When They’re More Cognitively Diverse’, Harvard Business Review, 30 March 2017, retrieved 23 November 2022, https://hbr.org/2017/03/teams-solve-problems-faster-when-theyre-more-cognitively-diverse; Syed M, Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking, John Murray, 2019.

The Institute for Government has recommended changes the government should make to increase external recruitment, including establishing new senior specialist roles, making provision for exceptional external candidates to be ‘poached’ by the government without a full recruitment process where appropriate, reforming the recruitment process to level the playing field between internal and external candidates, and fixing problems with onboarding civil servants. 362 Urban J and Thomas A, Opening Up: How to strengthen the civil service through external recruitment, Institute for Government, 7 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/civil-service-external- recruitment

* An evolution of a previous target that 2% of roles grade 7 and above should be filled by secondees.

Capability-based pay reform has stalled

The Institute for Government has previously recommended reforms to how civil servants are paid to discourage churn, incentivise the acquisition of subject-specific knowledge, improve retention and make the civil service more attractive to external recruits. 363 Nickson S, Thomas A, Vira S and Urban J, Pay reform for the senior civil service, Institute for Government, 9 November 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/pay-reform-senior-civil-service

Salaries should be increased (where there is a business case) to facilitate the attraction and retention of staff with in-demand skills. A greater proportion of pay should come in the form of bonuses for good performance. Financial incentives should be used to help to reduce churn. And the government should introduce properly funded capability-based pay – increasing the base salary of civil servants as they become more capable at their job. This is something the Declaration on Government Reform committed would be delivered for senior officials by the end of 2021, but has not happened. While not a transformative reform on its own, a well-designed capability framework, if funded, would signal to civil servants that the government values deeper subject expertise and specialist skills and that these are helpful for career progression.

364

Nickson S, Thomas A, Vira S and Urban J, Pay reform for the senior civil service, Institute for Government,

9 November 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/pay-reform-senior-civil-service

However, the emphasis on pay restraint has meant that any system introduced now could not be funded properly – and Institute for Government research has found that introducing this model with inadequate funding would be counter-productive.

365

Nickson S, Thomas A, Vira S and Urban J, Pay reform for the senior civil service, Institute for Government,

9 November 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/pay-reform-senior-civil-service

Failing to match capability assessments with requisite pay levels will undermine confidence in the system and its ability to motivate staff to improve their capability.

With the government’s proposed limited average pay award of 2%, there is instead a stronger case for using any headroom in the civil service’s pay envelope to boost pay for roles that require in-demand skills and offer financial support to civil servants in precarious financial positions – with many struggling due to the cost-of-living crisis, as outlined above.

Improving diversity and inclusion

A broader definition of diversity in the civil service should not mean a reduced focus on protected characteristics

In February 2022 the Cabinet Office published its new Civil Service Diversity and Inclusion Strategy 2022–2025, with the aim of promoting fairness and better performance within the institution.

366

Cabinet Office, Civil Service Diversity and Inclusion Strategy: 2022 to 2025, 24 February 2022, retrieved

14 November 2022, p. 10, www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-diversity-and-inclusion- strategy-2022-to-2025

The previous strategy ran from 2017 to 2022 and concentrated on improving the representation and inclusion of staff based on legally protected characteristics such as disability, ethnicity and sexual orientation.

367

Cabinet Office, A Brilliant Civil Service: Becoming the UK’s most inclusive employer, 16 October 2017, retrieved 14 November 2022, www.gov.uk/government/

publications/a-brilliant-civil-service-becoming-the-uks-most-inclusive-employer

The 2022 strategy was a change in direction, placing greater emphasis on socio-economic background (SEB) and for the first time incorporating the geographic location and professional background of civil servants under a new, broader definition of workforce diversity. It aims to go “further than the current Equality Act provisions by building on and expanding a previous focus on Protected Characteristics to deliver for all”.

368

Cabinet Office, Civil Service Diversity and Inclusion Strategy: 2022 to 2025, 24 February 2022, retrieved

14 November 2022, p. 10, www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-diversity-and-inclusion- strategy-2022-to-2025

Improving the diversity of geographic, professional and socio-economic backgrounds in the civil service is welcome but should not mean a reduced focus on protected characteristics, especially where disparities remain at senior level. The progress the civil service has made over recent decades in its representation of ethnicity, disability, sex and sexual orientation is not self-sustaining. This year, the proportion of minority ethnic officials in the senior civil service declined for the first time since 2015;

369

Cabinet Office, Civil Service statistics, retrieved 14 November 2022, www.gov.uk/government/collections/

civil-service-statistics

there are no longer any permanent secretaries from minority ethnic backgrounds. The new strategy includes no specific mention of gender, sexual orientation, age or faith; and, beyond a single reference – in the foreword – to people from minority ethnic backgrounds, includes no further mention of race. There is just one action specifically geared towards staff with disabilities: increasing the number of civil service organisations signed up to the Disability Confident Employer scheme.

The Cabinet Office should demonstrate to civil servants that the strategy’s broader definition of diversity does not mean a reduced focus on protected characteristics by explicitly recognising where work still needs to be done to improve the representation and inclusion of staff from these demographics. And all departments should have clear targets and plans to improve the recruitment, progression and inclusion of staff based on protected characteristics, particularly where their workforces are falling below benchmarks for the economically active population.

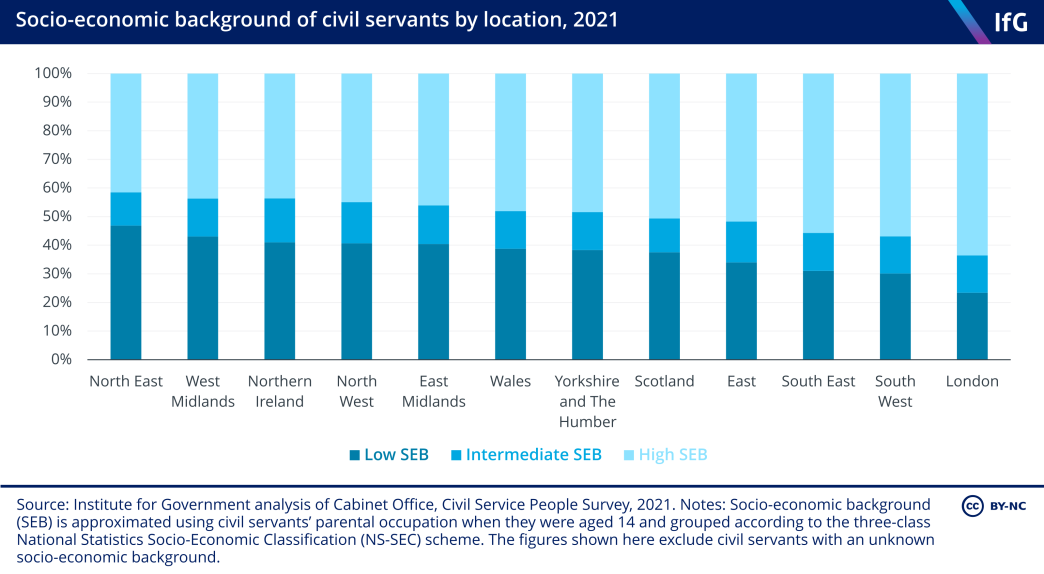

The new strategy makes a start on socio-economic diversity, but could go further

The new diversity and inclusion (D&I) strategy included some sensible plans to improve socio-economic diversity in the civil service. For instance, it reaffirmed a previous commitment to relocate 50% of senior officials outside London and the South East, recognising the strong links between geography and socio-economic diversity in the civil service. According to the Social Mobility Commission (SMC), promotion in the civil service is linked to securing certain high-profile jobs – ‘accelerator roles’ – with exposure to ministers and senior officials, such as in a private office or running a bill team. 370 Social Mobility Commission, Navigating the Labyrinth: Socio-economic background and career progression within the Civil Service, 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/987600/SMC-NavigatingtheLabyrinth.pdf Ministers and senior officials are based mainly in London, but only 23% of London-based civil servants are from a lower SEB compared to 47% in the North East. 371 Cabinet Office, Civil Service People Survey: 2021 results, 28 April 2022, retrieved 14 November 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-people-survey-2021-results Staff in this grouping who are based outside the capital may lack the economic resources to move there, making it harder for them to take prestigious positions based in Whitehall. 372 Social Mobility Commission, Navigating the Labyrinth: Socio-economic background and career progression within the Civil Service, 2021, pp. 37–52, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/ uploads/attachment_data/file/987600/SMC-NavigatingtheLabyrinth.pdf

The strategy also set out promising new plans to regularise the process for temporary promotions and to deliver an induction making explicit some of the ‘unwritten rules’ around accessing career development opportunities in the civil service – which the SMC argues is a major barrier to progression for working-class officials. 373 Social Mobility Commission, Navigating the Labyrinth: Socio-economic background and career progression within the Civil Service, 2021, pp. 37–52, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/ uploads/attachment_data/file/987600/SMC-NavigatingtheLabyrinth.pdf , pp. 44–48.

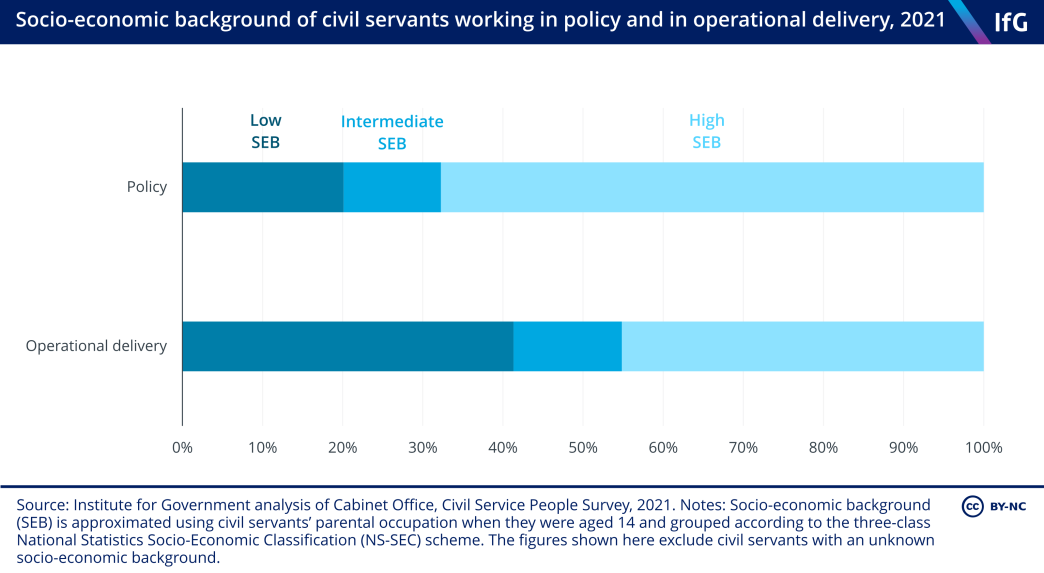

But the new strategy does not include plans to target the recruitment, retention or progression of lower SEB staff directly. Nor does it address barriers to progression based on the tendency of staff from lower SEBs to ‘self-sort’ into operational career paths in the civil service. 374 Social Mobility Commission, Navigating the Labyrinth: Socio-economic background and career progression within the Civil Service, 2021, pp. 37–52, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/ uploads/attachment_data/file/987600/SMC-NavigatingtheLabyrinth.pdf , pp. 53–57. Some 42% of civil servants in operational roles are from a lower SEB, twice the proportion as in policy roles (20%). Operational career paths often have ‘bottlenecks’ – a large number of junior staff competing for a small number of senior roles – and promotion elsewhere in the civil service usually requires demonstrating a broad range of skills, including experience of policy.

More needs to be done to provide opportunities for lower grade operational staff to gain policy experience and ‘demystify’ policy work. For instance, the civil service should review how hiring processes can help those who might self-select into operational career paths consider policy roles, and set up a cross-government scheme to support lower grade staff in departments and directorates that are heavily tilted towards operational roles in gaining policy experience.

The civil service must take action on inclusion if it is to achieve ‘diversity of thought’

The 2022–25 D&I strategy mentions the importance of “diversity of thought” in teams, meaning drawing on a range of backgrounds and experiences to improve policy making.

375

Cabinet Office, Civil Service Diversity and Inclusion Strategy: 2022 to 2025, 24 February 2022, retrieved

6 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-diversity-and-inclusion-strategy-

2022-to-2025, p. 9.

This partly entails recruiting people from different demographic backgrounds who can use their experience to consider how government policy affects different groups. It will also involve more external recruitment of people with diverse professional experiences and training who can approach problems in different ways to find and operationalise solutions.

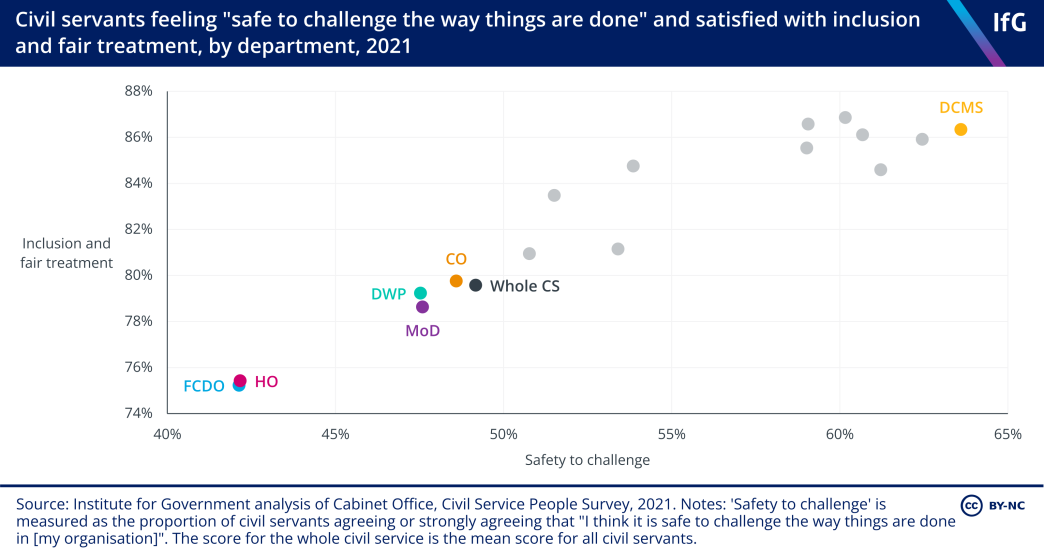

It is not enough to improve the way the civil service recruits, however. The ‘groupthink’ in the civil service – both in the sense of demographic background and professional experience – also results in people feeling unable to fully participate in the decision making processes. According to the Civil Service People Survey for 2021, only a little over half (55%) of civil servants felt “safe” to challenge the way things are usually done in their organisation. There are a number of reasons for the civil service to become a more inclusive working environment, and one of the most important is that it would help the civil service tap into a variety of perspectives.

Departments with lower scores on inclusion and fair treatment tend to have a lower proportion of staff who feel comfortable challenging the way things are done. The FCDO and the Home Office have the lowest proportions of employees satisfied with inclusion in their department – and in both only 42% of staff feel “safe” challenging the way things are done. Since the merger of FCO and DfID, the department’s scores have fallen for both safety to challenge (15 percentage points) and inclusion (5pp), suggesting the organisation needs to improve its culture to increase ‘diversity of thought’.

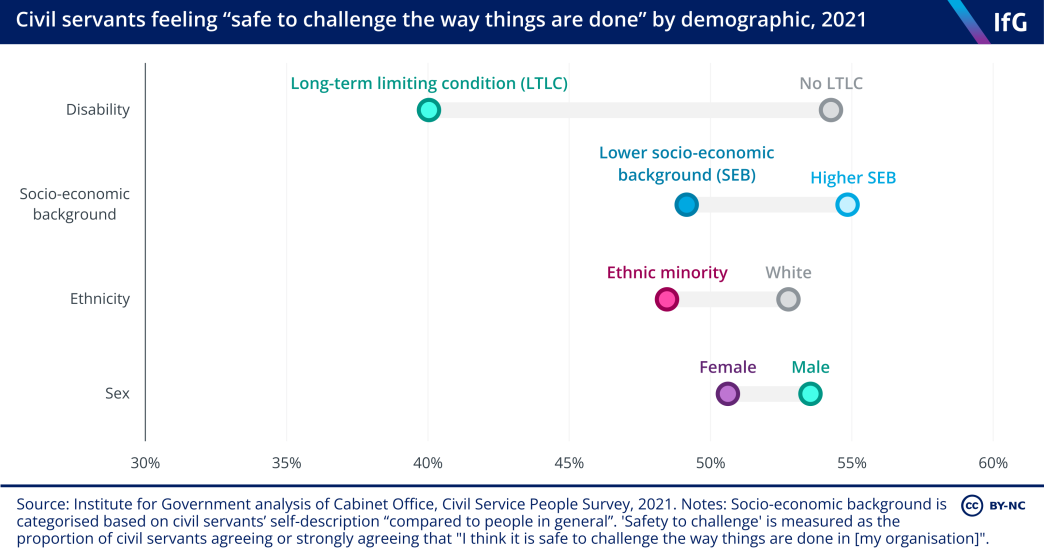

The strategy also emphasises varied geographical, socio-economic and career backgrounds to avoid ‘groupthink’. This is evident in the 6 percentage point difference between the proportion of civil servants from lower (49%) and higher (55%) SEBs who feel comfortable challenging their organisation’s practices.

But the civil service should not overlook protected characteristics such as disability, ethnicity and sex in its focus on ‘diversity of thought’. Only 40% of civil servants with a long-term limiting condition feel able to challenge the way things are done, compared with 54% of those without. Minority ethnic (48%) and female (51%) civil servants are also less likely to feel comfortable voicing dissenting opinions than their white (53%) and male (54%) colleagues.

If the civil service wants to promote innovation, it should ensure that staff from different backgrounds – including minority ethnic, female and disabled civil servants – feel supported to draw on their experiences and provide their insight. But the strategy sets out few specific plans to achieve this. For example, the Institute recommended in December 2022 that the government’s new ‘Inclusion at Work Panel’ should proactively research and trial interventions to address staff experiences of exclusion and unfair treatment.

376

Bishop M, A Crossroads for Diversity and Inclusion in the Civil Service: Assessing the 2022 D&I strategy, 2022, retrieved 7 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/diversity-inclusion-civil-

service, p. 26.

Data and digital

In 2022 the government launched its roadmap for digital and data, Transforming for a Digital Future, which runs to 2025. 377 Central Data and Digital Office, Transforming for a digital future, June 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/roadmap-for-digital-and-data-2022-to-2025/transforming-for-a-digital-future-2022-to-2025-roadmap-for-digital-and-d… This gave some overdue clarity to digital leadership in government, with the Central Digital and Data Office (CDDO) taking charge of overall digital strategy and the Government Digital Service (GDS) given a supporting role in helping departments digitise their operations and public services. The shift acknowledged that digital skills, through Digital, Data and Technology (DDaT) professionals, are more embedded in individual departments than previously and are responsible for providing services at the department level.

To implement a unified digital approach, the CDDO has said that it aims to normalise departmental practices towards data, specialist recruitment and skills. The strategy sets ambitious ‘missions’ about where the civil service wants to be in its digital operations, but is less explicit about how it will achieve these goals. However, it adopts a realistic, staggered approach to prioritise frequently used public services and “critical” data assets. It is sensible that senior leaders have been named responsible for each mission and that achievements will be measured through six-monthly reviews.

The strategy recognises the need to recruit, develop and retain digital technology skills more consistently between departments. Historically, DWP and GDS have been seen as performing well at recruiting DDaT professionals, while departments with less developed technical strengths have found recruitment difficult. In response, the CDDO strategy identifies the need to standardise recruitment processes across Whitehall through the creation of a single ’front door’ for technical applicants before being assigned to specific departments, as well as the need to bring salary levels for DDaT professionals closer to equivalent industry standards across departments, and improve consistency across the civil service, using the DDaT Pay Framework. But these initiatives will require commitment from all departments.

The strategy also gave an insight into how government intends to use digital skills in the future – namely to provide more than £1bn in efficiency savings by 2025 via better use of data and technology, including wider use of automated systems. The roadmap rightly explains that this requires more consistent data storage and systems and improved data quality, which government has struggled with in the past. Incompatible security systems and equipment that had to be resolved during the DfID and FCO merger in 2020, for example, hampered the government’s response to the Russia– Ukraine conflict, 378 Smith B, ‘Foreign Office IT woes still causing ‘chaos’ as Ukraine war unfolds’, Civil Service World, 28 February 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/foreign-office-it-woes-still-causing-chaos-as-ukraine-war-unfolds while data gaps and poor data quality limit the government’s understanding of front-line public service performance. 379 Atkins G and Hoddinott S, Neighbourhood services under strain, Institute for Government, 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/neighbourhood-services-under-strain To improve, the government requires more consistent data and collaboration between departments.

Disruption at the top of CDDO has slowed reform

To achieve the desired pace of digital transformation there needs to be less turnover of CDDO leadership. The civil service has struggled to fill senior digital leadership roles. After failing to hire a chief digital and information officer in September 2019 and August 2020, an executive director of the CDDO was appointed in January 2021 on a fixed 18-month contract. A chief digital officer was then appointed in September 2022 following the executive director’s scheduled departure in summer 2022.

However, the change in leadership also saw both the interim chief data officer and the interim chief technology officer leave in 2022 without replacements in place. Salary constraints have made recruitment and retention of digital leaders particularly challenging and CDDO was only able to temporarily fill these initial positions by attracting people on short-term contracts, effectively as secondments.

Despite this, some progress has been made, including building the legitimacy of the CDDO by creating the chief technology officer council (in late 2021) 380 Bailey D, ‘Introducing the government’s Chief Technology Officer Council’, blog, Technology in Government, 30 November 2021, retrieved 19 January 2023, https://technology.blog.gov.uk/2021/11/30/introducing-the-governments-chief-technology-officer-council and chief digital officer council in 2022 381 Science and Technology Committee, ‘Oral evidence: The Right to Privacy: Digital Data, HC 97’, 8 June 2022, retrieved 19 January 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/10352/html to bring together digital leaders from across departments to support the sharing of best practice. But the personnel changes across most senior roles will inevitably disrupt key digital reforms, especially standardisation of data schema (essential for achieving better digital services and data sharing initiatives) or finding and assessing the risks and costs of outdated and unfit-for-purpose legacy IT equipment across departments. Consistency in digital leadership is important, especially when managing large-scale system updates, so it will be in the government’s interest to prioritise this in 2023 and beyond.

Fair progress has been made on digital skills, services and security

Skills

A recurring limitation in achieving digital reform in the civil service has been a lack of digital literacy. A 2022 poll on digital skills by the Global Government Forum found that 40% of officials have basic, very little or no knowledge of how data and technology could transform public services. 382 Global Government Forum, ‘UK civil service digital skills report’, December 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.globalgovernmentforum.com/uk-civil-servants-highlight-barriers-to-digital-transformation-in-government Therefore the civil service must do more to improve digital literacy. The CDDO launched a minimum set of Digital, Data and Technology Essentials for all civil servants to meet and hosted an ‘Autumn of Digital Learning’ for senior leaders. 383 Central Digital and Data Office, ‘Digital, Data and Technology essentials for senior civil servants’, 31 May 2022, retrieved 19 January 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-data-and-technology-essentials-for-senior-civil-servants/digital-data-and-technology-essentials-for-senior… B, ‘CDDO’s Autumn of Digital Learning’, blog, Central Digital and Data Office, 21 November 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, https://cddo.blog.gov.uk/2022/11/21/cddos-autumn-of-digital-learning

It is also arranging regular meetings of its chief data officer and chief technology officer councils every month, and permanent secretaries every two months, to better share best practice across departmental leadership.

The CDDO will need to keep up this work if it is to meet its target of improving the skills of 90% of senior civil servants on digital and data awareness – and its next task, of rolling out training at scale across all civil servants, will be much bigger.

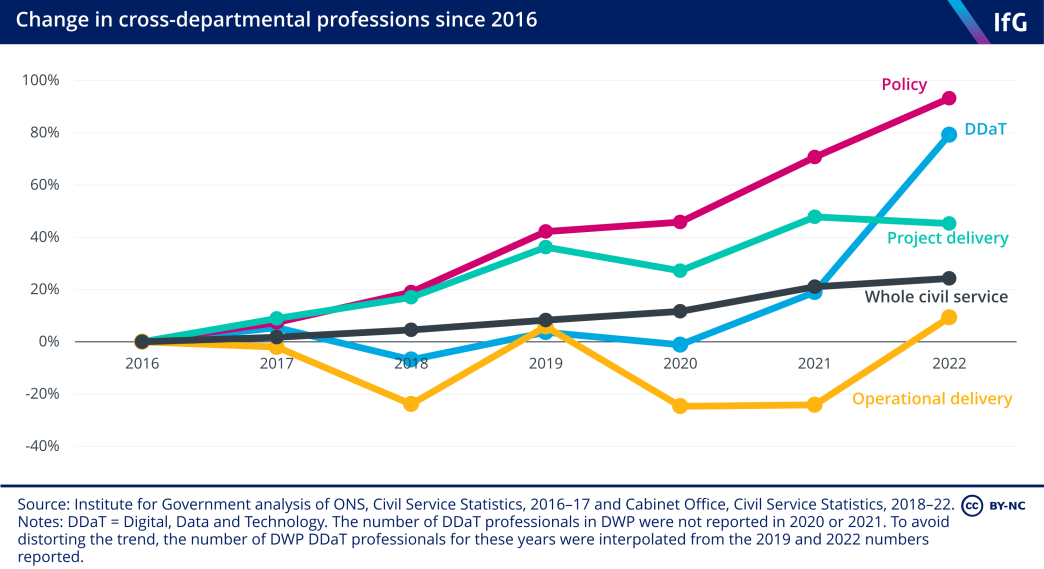

While general data literacy continues to improve, if slowly, it has coincided with the number of DDaT professionals in the civil service continuing to grow. DDaT is the third largest civil service profession (after operational delivery and policy) and has grown by 80% since 2016. This has come as departments increasingly see the benefit of working with data to evaluate policy decisions or allocate resources – this was especially important during the pandemic response 384 Freeguard G and Shepley P, The Clinically Extremely Vulnerable People Service: Summary of a private roundtable, Institute for Government, 2022, retrieved 15 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/clinically-extremely-vulnerable-people-service and will be integral to better targeting of policies and public services in the future. For example, the policy of universal energy bill support in 2022 could have been targeted more efficiently by improved use of various government datasets. 385 Bartrum O, ‘Better use of data is needed for better energy support policies’, Institute for Government, 5 December 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/blog/better-use-data-needed-better-energy-support-policies In acknowledgement of these trends, the Treasury appointed its first chief data officer in 2022. 386 Lago C, ‘HM Treasury appoints first Chief Data Officer’, Government Transformation Magazine, 8 September 2022, retrieved 19 January 2023, www.govx.digital/people/hm-treasury-appoints-first-chief-data-officer

However, it is not clear how the civil service aims to achieve the digital skills needed to support longer-term public service reform. Repeated claims have been made about the potential of automation of services, making use of machine learning or artificial intelligence, but awareness of these technologies across the civil service remains low and training in them even lower, at just 5% of polled civil servants. 387 Global Government Forum, ‘UK civil service digital skills report’, December 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.globalgovernmentforum.com/uk-civil-servants-highlight-barriers-to-digital-transformation-in-government Given the risks and opportunities of utilising these technologies in public services, the civil service must work harder and faster at building skills and confidence in their application.

Services

In 2022 the Government Digital Service (GDS) started beta testing its GOV.UK One Login for government services, a long-term priority project intended to simplify how the public accesses government services, such as applying for and monitoring a criminal records check or ordering a birth, death or marriage certificate. The Disclosure and Barring Service and Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency both started to use One Login last year, with the first users experiencing the service in July 2022. 388 Cabinet Office, ‘One Login for Government Accounting Officer assessment’, September 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/cabinet-office-accounting-officer-assessments/20-september-2022-one-login-for-government-accounting-officer-assess… This has been complemented with a One Login identity checking app launched in August.

The previous Verify government account system can no longer open new accounts for users, with the eventual goal of transferring existing Verify accounts into One Login. GDS believes 3.2 million users will have had access to the One Login service by the end of 2022, creating an opportunity to learn and continue to refine the product. There will need to be ongoing security testing and public engagement, such as the public consultation into departmental data sharing for online government services.

389

Cabinet Office and Government Digital Service, ‘Cabinet Office launches consultation on departmental data

sharing’, 4 January 2023, retrieved 5 January 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/cabinet-office-launches-consultation-

on-departmental-data-sharing

The government has also made progress in its Shared Services Strategy, after stalling between 2015 and 2021. 390 Maude F, ‘Review of the cross-cutting functions and the operation of spend controls’, Cabinet Office, 22 July 2021, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-the-cross-cutting-functions-and-the-operation-of-spend-controls The strategy is an attempt to combine core digital functions from various departments to a central cloud-based operation that will save time and cost associated with administrative functions, and will group 20 departments into five clusters by 2028 (previously 2025). Two of these have started to implement new systems. 391 Comptroller and Auditor General, Government Shared Services, Session 2022-23, HC 921, National Audit Office, 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.nao.org.uk/reports/government-shared-services Ultimately, the government aims to have five cloud-based shared service centres, delivering efficiency savings of 10–15% in operation costs. This work is being complemented by developing common data standards, but remains in an early stage and the Cabinet Office currently has no means of or metrics by which to monitor progress. 392 Ibid. Given the difficulties in achieving this programme, the government must set out and track milestones to identify and correct any problems as they occur to prevent further delays.

Identifying problems early on will be essential given the difficulty with delivering government-wide data platforms on time. For example, the Office for National Statistics’ Integrated Data Service was scheduled to be accessible to researchers outside of government in spring 2022, but this has now been delayed to 2023. 393 Brecknell S, ‘Red light, green light: examining the government’s progress on improving its performance’, Civil Service World, 22 April 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/in-depth/article/declaration-on-government-reform-progress-civil-service-performance-partnership-rag-rating

Security

In line with the 2022 Government Cyber Security Strategy, 394 Cabinet Office, ‘Government Cyber Security Strategy: 2022 to 2030’ February 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-cyber-security-strategy-2022-to-2030 departments will have their cyber resilience externally audited to better understand risk across government. 395 Trendall S, ‘Departments to undergo independent audits of cyber resilience’, Public Technology, 7 April 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.publictechnology.net/articles/news/departments-undergo-independent-audits-cyber-resilience This is in response to an increasing number of cyber threats, including a serious attack on the FCDO in January 2022. 396 Beer E, ‘Foreign Office hacked in “serious cyber security incident”’, The Stack, 2 August 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, https://thestack.technology/foreign-office-hacked-fcdo-cyber-attack In 2021, the National Cyber Security Centre responded to 777 incidents, 40% of which were targeted at public sector entities. The government is right to aim to improve cyber resilience and increase awareness of cyber risk across the state, especially when tightened budgets may otherwise prompt departments to seek to make savings on cyber security investment.

Legacy IT investment must be protected to safeguard future efficiency

Despite these successes in developing digital literacy and digitised public services, legacy IT issues remain a key stumbling block for digital reform. For instance, legacy technology in DWP was reportedly responsible for restricting the uprating of benefits to once per year, preventing any additional increase until April 2023 despite rapid inflation throughout 2022. 397 Trendall S, ‘Ageing DWP IT ‘stopped Sunak raising benefits to keep pace with inflation’’, Civil Service World, 10 May 2022, retrieved 14 December 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/ageing-dwp-it-prevented-sunak-increasing-benefits-with-inflation While this issue will eventually be corrected by the renewed migration of benefits claimants on to Universal Credit, it shows the degree to which certain public-facing departments are directly affected by outdated IT systems.

But finding and upgrading legacy IT systems*is hard. The civil service is yet to complete its legacy IT mapping exercise, begun in 2021, and so is unaware of where these systems exist in departments and the subsequent risk they create.

398

House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, Challenges in implementing digital change: Thirtieth Report of

Session 2021-22 (HC 637), The Stationery Office, 2021.

Unknown legacy IT issues frequently cause programme delays and overspend, and were partly responsible for delays in implementing common data standards within the Ministry of Defence during its work on the Digital Strategy for Defence.

While some could continue to function adequately until their retirement, others would benefit from replacement to make the public service they support more robust and reliable, sooner. This will require sustained investment over time – projects will often take longer to upgrade than a four- to five-year spending review period. Upgrading the most at-risk legacy systems is a key aspect of the CDDO’s roadmap for digital and data, but before that it needs to know which these are. At present the method for assessing legacy risks remains uncertain.

* Legacy IT systems are classed as IT systems that run on outdated or obsolete technology and that are no longer fit for purpose.

Public bodies and appointments reform

The government has made progress with its public bodies review programme, despite ministerial churn

The Declaration on Government Reform published in June 2021 included a commitment to a create a new “review programme for Arm’s Length Bodies”.

423

Cabinet Office, Declaration on Government Reform, 15 June 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/declaration-on-government-reform/declaration-on-government-reform

This commitment was met in April 2022 when the Cabinet Office published new guidance on how public body reviews should be carried out.

424

Cabinet Office, ‘Guidance on the undertaking of Reviews of Public Bodies’, GOV.UK, updated 19 December 2022, retrieved 30 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-bodies-review-programme/

guidance-on-the-undertaking-of-reviews-of-public-bodies

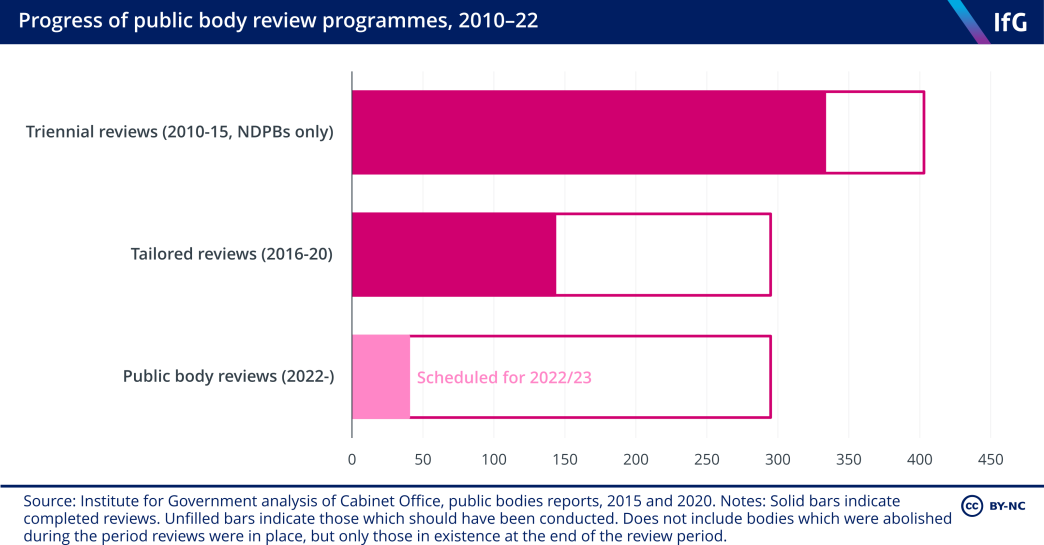

This guidance launched the latest in a series of review programmes that have sought to identify unnecessary bodies and improve the performance of those remaining.

425

Cabinet Office, ‘Triennial reviews: guidance and schedule’, GOV.UK, last updated 9 December 2014, retrieved 30 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/triennial-reviews-guidance-and-schedule; Cabinet Office, ‘Tailored reviews of public bodies: guidance’, GOV.UK, last updated 24 May 2019, retrieved 30 December

2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/tailored-reviews-of-public-bodies-guidance

Previous review programmes have been criticised for failing to meet their targets (fewer than half of bodies in 2020 had been reviewed in the previous five years).

426

Comptroller and Auditor General, Central Oversight of Arm’s Length Bodies, Session 2021-22, HC 297, National Audit Office, 23 June 2021, retrieved 30 December 2022, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Central-oversight-of-Arms-length-bodies.pdf; Lilly A, Clyne R, Thomas A and others, Whitehall Monitor 2022, Institute for Government, 2022, retrieved 9 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/whitehall-monitor-2022

These changes to the review programme are welcome and should result in more effective reviews than in previous waves. However, while the guidance makes clear that reviews should consider the whole “delivery system” of departments, including the way departments sponsor their bodies, there is still a strong focus on examining the body itself, and particularly on cost-saving. The guidance requires lead reviewers to give an indication of where 5% of day-to-day savings can be found within one to three years, and is particularly focused on increased efficiency and reducing the “burden on the taxpayer”. 427 Cabinet Office, ‘Guidance on the undertaking of Reviews of Public Bodies’, GOV.UK, updated 19 December 2022, retrieved 30 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-bodies-review-programme/guidance-on-the-undertaking-of-reviews-of-public-bodies

Improved value for money is welcome, although the government should be wary of setting arbitrary financial targets without strong reason as a way to improve performance – particularly as both efficiency and performance improvement may require more investment in the short term. The latest reform programme has not so far focused on the so-called ‘numbers game’ – trying to reduce the number of public bodies as an aim in itself. This is welcome as a focus on numbers alone can lead to simply recategorising bodies, or merging functions that do not necessarily work well together, rather than on improving delivery and value for money. It is also welcome that the initial list of bodies to be reviewed as part of the programme is focused on relatively large organisations and ones whose responsibilities have changed after Brexit, such as Ofcom and the Civil Aviation Authority. 428 Cabinet Office, ‘List of Public Bodies for Review in 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 19 December 2022, retrieved 30 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-bodies-review-programme/list-of-public-bodies-for-review-in-202223

Improvements have been made in the public appointments process, but problems remain

The government has committed to making improvements to the way the public appointments system works, in response to increasing criticism of the slowness, opacity and potential for patronage in the current system. The Institute for Government’s 2022 report found problems with delays in appointments and a growing number of unregulated appointments. The Institute recommended government publish data on the causes of delays and a list of unregulated appointments, among other changes. 429 Gill M and Dalton G, Reforming Public Appointments, Institute for Government, 18 August 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/reforming-public-appointments Many of these recommendations were echoed more recently in a report by the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee. 430 House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Propriety of Governance in Light of Greensill: Fourth Report of Session 2022–23, HC 888, 2 December 2022, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/31830/documents/178915/default The government intends to respond to this report, as well as the Committee on Standards in Public Life’s report that made similar recommendations, 431 Committee on Standards in Public Life, Upholding Standards in Public Life, GOV.UK, 1 November 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/upholding-standards-in-public-life-published-report in 2023.

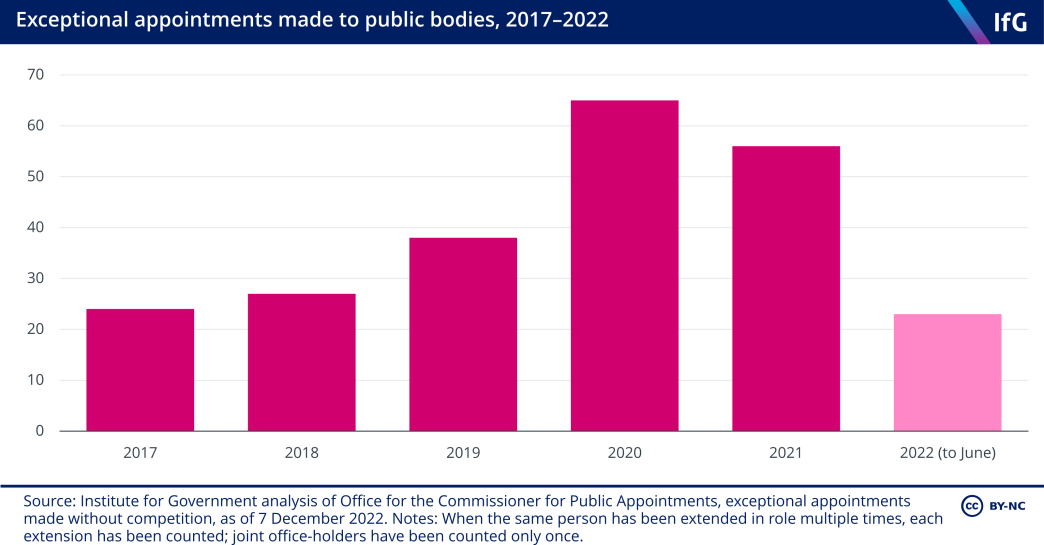

The government has made some progress in resolving these problems. The number of exceptional appointments, generally made to fill gaps left by delayed appointments processes, seems to be falling. However, this progress may have been stalled by ministerial churn and a ‘caretaker’ government in office over the summer that was (rightly) cautious about making appointments. It is difficult to assess the impact of this period as the latest data on exceptional appointments runs only until June 2022.

The government has made some positive steps in professionalising the appointments system over the past year, including launching a new website to list jobs, 432 Cabinet Office, ‘Apply for a public appointment’, GOV.UK, [no date], retrieved 30 December 2022, https://apply-for-public-appointment.service.gov.uk/roles a new scheme to help aspiring board members, 433 Department for Levelling Up, Communities and Housing, ‘New programme aimed to boost diversity in boardrooms’, GOV.UK, 2 September 2022, retrieved 30 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/news/new-programme-aimed-to-boost-diversity-in-boardrooms and a better training and induction offer to new appointees. There have also been some encouraging noises from government on policy changes, including a commitment to regulate the appointment of government non-executive directors, and the suggestion that government could publish a list of other non-regulated jobs. 434 Case S, Oral evidence to Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee inquiry into Propriety of governance in light of Greensill, HC 212, 28 June 2022, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/10485/pdf, Qs 471, 528–9. This should happen as soon as possible, and be accompanied by a clear rationale as to why each role is unregulated.

These commitments do not, however, go far enough in tackling the problems in the system. The proportion of appointees declaring ‘political activity’ remains low, but this declaration is only voluntary. More importantly, the pressure put on the appointments system under the Johnson government, and its consistent failure to deliver appointees to key positions on time, demonstrate that change is still needed. The latest data from the Commissioner for Public Appointments suggests just a quarter of appointments processes were completed within the government’s three-month ‘aim’ in 2021/22. 435 Commissioner for Public Appointments, OCPA Annual Report 2021/22, December 2022, https://publicappointmentscommissioner.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/OCPA-Annual-Report-2021-22.pdf, p. 5.

To tackle these issues, the government should collect, and eventually publish, data to track appointments properly and identify the causes of delays. And to restore trust, it should extend and formalise the powers of the commissioner for public appointments to regulate the system. 436 Gill M and Dalton G, Reforming Public Appointments, Institute for Government, 18 August 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/reforming-public-appointments

Devolution and decentralisation

Whitehall must recognise the push for devolution and decentralisation