Stopping the civil service fast stream is a short-sighted mistake

Pausing the civil service fast stream for “at least a year” is a consequence of the government’s wrong-headed approach to workforce management

Rhys Clyne argues that pausing the civil service fast stream for “at least a year” is a consequence of the government’s wrong-headed approach to workforce management

The government has decided to pause recruitment to its long-standing graduate development programme as part of efforts to achieve the government's target of reducing the civil service headcount by 91,000 to its pre-Brexit level by 2025. Such a pause neglects both the value the government draws from the scheme and the potential it has to improve.

Arbitrary headcount targets are an inefficient way to manage the civil service

Headcount targets are a poor starting place from which to manage any workforce because they incentivise measures – such as blanket recruitment freezes – that most directly reduce staffing numbers regardless of the additional costs created or value lost.

Scrapping or pausing the fast stream is a good example of this inefficiency. Around 1,000 fast streamers are recruited into its 15 schemes every year, at an annual cost of approximately £41m to government. Pausing the scheme would generate that small saving for ministers to reallocate to other priorities. But that does not take into account any of the value lost to government or the additional costs created.

While the fast stream could be improved, it is an asset to the UK government. The civil service has been named The Times’ top graduate employer for the last three years in a row. The fast stream has proven a reliable way to recruit talented, early career graduates into public service who might otherwise have chosen different paths. With an average annual salary of £27,000–28,000, fast streamers provide good value for money to government, often quickly taking on more responsibilities and then progressing to senior jobs across the civil service.

Pausing the fast stream would damage the quality of policy advice available to ministers, cutting off one avenue for injecting fresh perspectives into departments. Over time it will also make it harder for the government to reduce its reliance on expensive contractors, given consultancies offer similar skills to those of fast streamers and recruit from the same pools of graduates. The government may soon be paying over the odds to employ the same people temporarily, as consultants, who they might otherwise have recruited permanently into the civil service via the fast stream.

Pausing the fast stream will prove a false economy that makes sense neither in the short nor long term. Even if the pause only lasts a year, that choke on talent will echo into the future. And it is characteristic of the government’s wider approach to securing financial savings from workforce reductions. Ministers say that scrapping 91,000 roles will save £3.5bn, but that also fails to account for additional costs created like redundancy or other payments, nor does it reflect potential consequences for the government’s delivery capability.

Pausing the fast stream will make it harder to improve the diversity of the civil service

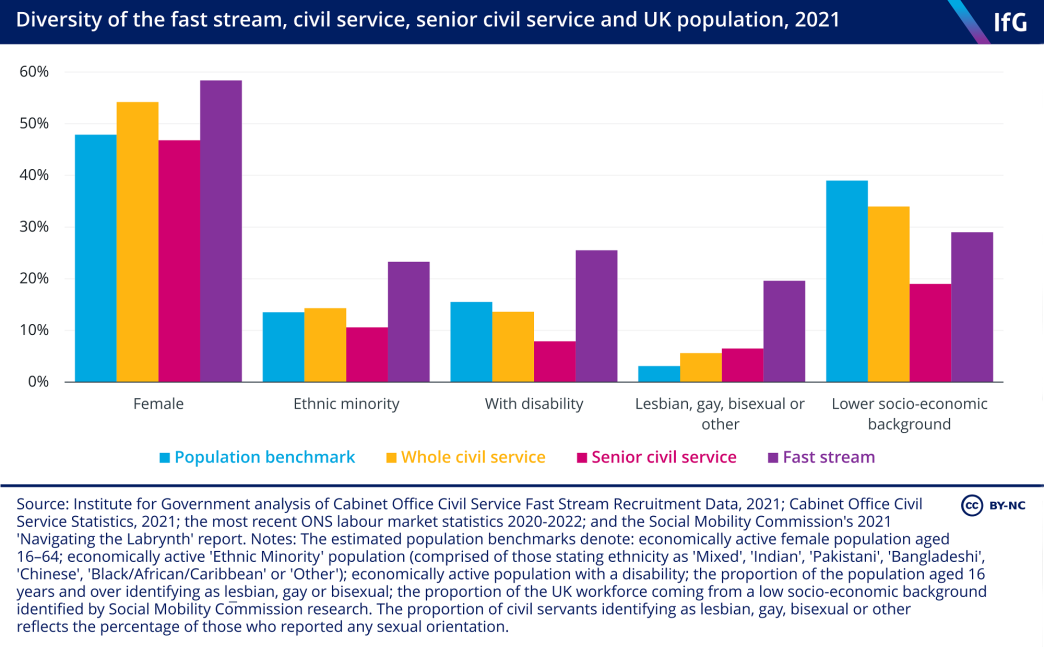

The fast stream is an effective tool the civil service has used in recent years to make its workforce more representative of British society. The scheme continues to underrepresent people from low socio-economic backgrounds, a problem that should be addressed as a priority. But it is at least as, or more than, representative on the grounds of sex, ethnicity, disability and sexual orientation. On these characteristics, the fast stream outperforms both the whole civil service and the senior civil service.

In the short term diverse teams bring different experiences and fresh perspectives to the table. This will help inject the “diversity of thought” ministers want to bring to government policy making.[1]

And in the long term, many of today’s fast streamers will go on to be tomorrow’s civil service leaders. If the civil service is going to close the remaining gaps in representation among its senior ranks, and secure the progress already made, the fast stream is part of the answer.

The fast stream still needs reform

The fast stream is, of course, not perfect and like the rest of the civil service should not be immune to change. It continues to grapple with its legacy and perception as a scheme dominated by white, middle-class Oxbridge graduates. It underrepresents graduates from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Ethnic minority applicants are less successful than white applicants.[2] It can also incentivise officials to pursue generalist policy careers with rapid turnover between roles, at the expense of deeper subject-matter expertise.

But these are opportunities to improve the scheme rather than reasons to scrap it. Substantial progress has been made improving the specialisation of the fast stream since 2010, with the introduction of dedicated, technical schemes in high-priority areas such as digital, data and technology, commercial and project delivery. This progress needs to continue to strengthen the talent pipelines in these functions as well as their standing in departments.

This government also says that it wants to increase the exchange of knowledge and talent between the civil service, other sectors and other parts of the public sector (known as “porosity” in civil service jargon).[3] There are many other successful graduate schemes across the wider public sector[4], so ministers and senior officials should develop a cross-public sector option between the fast stream and its public sector equivalents. Giving graduates the chance to experience public service in local government and the NHS, as well as the civil service, would improve exchange and understanding between the layers of government – one of the major barriers to better co-ordination and collaboration across the British state.

Pausing the fast stream is just one consequence of harmful short termism that follows from the government’s arbitrary target for civil service job cuts. Ministers must rethink this damaging decision and instead put their efforts into more worthwhile government reform.

- Civil Service Diversity and Inclusion Strategy: 2022 to 2025, www.gov.uk/government/publications/civil-service-diversity-and-inclusion-strategy-2022-to-2025/civil-service-diversity-and-inclusion-strategy-2022-to-2025-html

- Civil Service Fast Stream: recruitment data 2019, 2020 and 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1039977/2021-CS-Fast-Stream-External-Annual-Report-Tables-pdf-15.11.21.pdf

- Declaration on Government Reform, www.gov.uk/government/publications/declaration-on-government-reform/declaration-on-government-reform

- Such as the Local Government Association’s National Graduate Development Programme or the NHS Graduate Management Training Scheme.

- Supporting document

- whitehall-monitor-2022.pdf (PDF, 8.26 MB)

- Topic

- Civil service

- Publisher

- Institute for Government