Whitehall Monitor 2024: Part 2: How the civil service needs to change

Recommendations for civil service reform covering the workforce, ministers, the centre of government, policy making, digital and AI, and resilience.

Summary

The prospect of a stable government – of whichever political makeup – with a full parliamentary term ahead of it following this year’s general election represents a critical opportunity for civil service reform.

Neither the civil service nor government can afford to waste it. Ministers and civil service leaders should be prepared, early into the new parliament, to acknowledge long-standing and deep-rooted problems in Whitehall. They should set in train more fundamental reforms to the civil service than have been attempted in the past decade.

We have identified six key areas in which the civil service should change to improve UK government over the next parliament.

- The civil service workforce could be much more effectively planned, to help the civil service become more efficient and to improve its ability to recruit and retain top talent.

- The centre of government should be better able to support the prime minister to set strategy across government and align the government’s priorities, policy and budgets.

- Civil servants’ relationships with ministers should be reset and clarified to strengthen relationships and accountability within government.

- Whitehall policy making should be more long-term, open, cross-cutting and imaginative to deal with the challenges facing the UK.

- The civil service needs to accelerate its efforts to keep up with the digital and AI revolution that will change its work fundamentally. This will require progress to transform legacy IT and improve external recruitment and talent retention.

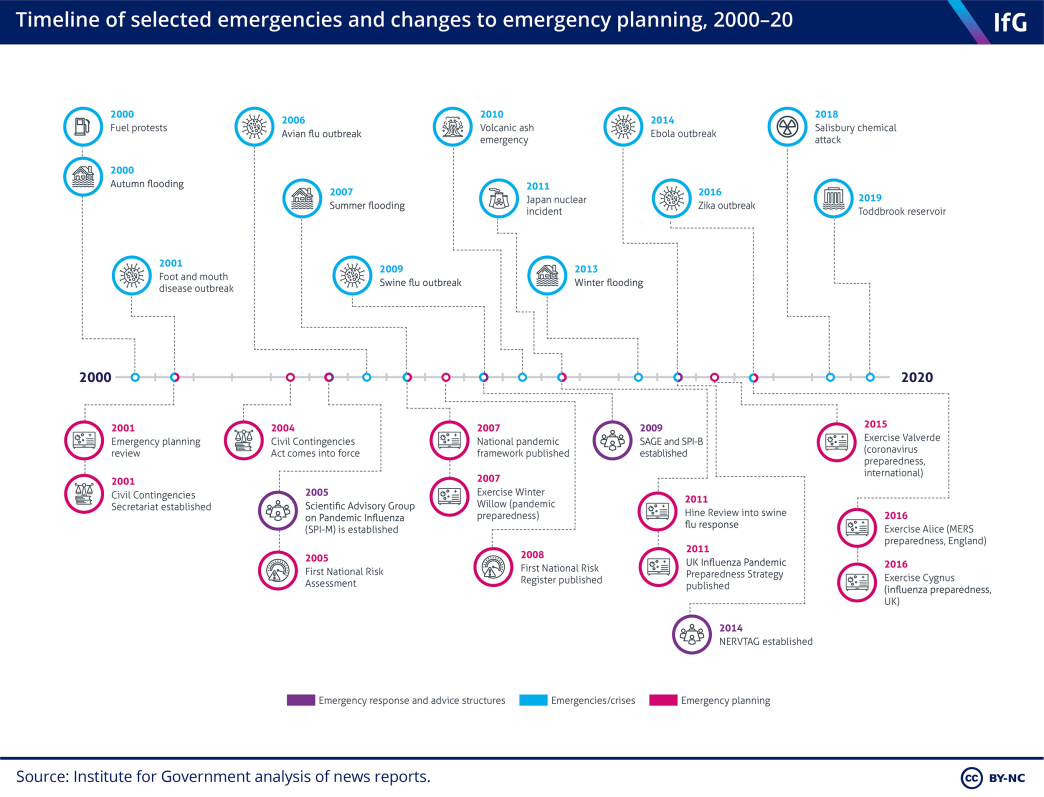

- Improvements are urgently needed to the structures and processes which keep the UK resilient and prepared for crises of the future – as the Covid Inquiry is showing.

Momentum for serious reform of Whitehall seems to be quietly building. In July 2023 the then Cabinet Office minister, Jeremy Quin, delivered a speech on his priorities for the civil service, covering its skills – especially on digital – and efficiency. This was followed in November, when Lord Maude set out proposals for a radical shake up of the civil service – and UK government – in his Review into civil service governance and accountability, which we discuss below.

The opposition, too, is targeting reform. Keir Starmer has appointed former senior civil servant Sue Gray as his chief of staff, and has tasked her with developing plans for reforming Whitehall should Labour win the next election.

There is more consensus on the problems facing the civil service than on many other questions of policy. Plenty of civil servants, politicians and outside experts will recognise the issues we have identified above. It is welcome that leading figures are considering their priorities for reform in the next parliament.

This second part of Whitehall Monitor aims to support, and further, this debate. It offers the Institute for Government’s own priorities for reform in these six crucial areas.

The civil service workforce

Poor workforce planning has hampered civil service effectiveness

The civil service is an enormous organisation – in many ways better thought of as a sector – consisting of more than half a million employees. With officials in roles ranging from permanent secretaries to prison officers, it is inevitably difficult to cohere and plan the workforce. But the current incoherence prevents the civil service from reaching its full potential. It has long been undermined by deep-rooted workforce issues, as demonstrated throughout much of Part 1 of this report:

- More strategic workforce planning would help the civil service to improve its recruitment, development and retention of top talent

- Changes to pay and career structures, and civil service culture, could reduce the excessive turnover of officials, strengthening institutional memory, expertise and delivery

- Reforms to recruitment and interchange with other sectors could open up civil service culture and ensure government can make the most of outside expertise

- More senior specialist roles would dismantle barriers to career development and help the government to value staff for their knowledge and expertise, not just managerial skills

- Continuing to make the civil service less London-centric is important for increasing its available talent pool and breadth of experience

- More competitive pay would strengthen the civil service’s brand as an employer, reducing the pressures on recruitment and retention.

Many of these are long-running issues. As long ago as 1968, Lord Fulton argued against excessive turnover, or ‘churn’, saying that: “It cannot make for the efficient despatch of public business when key men rarely stay in one job longer than two or three years before being moved to some other post”. 352 Fulton J, The Civil Service: Report of the Committee 1966–68, Cmnd 3638, The Stationery Office, 1968. Since the publication of the Fulton report at least five government reform plans, including the 2021 Declaration on Government Reform, have recommended greater external recruitment to the civil service. 353 Urban J and Thomas A, Opening Up: How to strengthen the civil service through external recruitment, Institute for Government, 1 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/civil-service-external- recruitment Similarly, seven commitments have been made to increase secondments since 1988. 354 Cabinet Office, Independent Review of Governance and Accountability in the Civil Service: The Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham, GOV.UK, 13 November 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-governance-and- accountability/independent-review-of-governance-and-accountability-in-the-civil-service-the-rt-hon-lord- maude-of-horsham-html#annex-4-interchange-with-sectors-outside-the-civil-service---making-it-more-porous-a-case-study But despite the efforts of previous reformers, these problems have not been solved.

After some lost years, the Sunak government has taken small steps in the right direction

After Boris Johnson won the 2019 general election his chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Michael Gove, and chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, had grand plans to reform Whitehall and the people who worked in it. They had the political capital to do so, Johnson having won an 80-seat majority, but little progress was made during the rest of the parliament. The distraction of the pandemic was a legitimate justification for this in 2020 and 2021. But Cummings’ adversarial style made enemies instead of allies, while the Declaration on Government Reform, a thoughtful plan led by Gove and the cabinet secretary, Simon Case, ended up a further example of a missed opportunity to achieve real change. 355 Thomas A and Urban J, Anything to declare?: A progress report on the Declaration on Government Reform – and what should come next, Institute for Government, 21 April 2022,www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/ publication/government-reform-progress

Four years on, the Sunak government has taken some tentative steps in the right direction. A pay settlement was reached that eased the industrial dispute of winter 2022/23 and recognised, with a one-off payment to most officials, the impact of the cost-of-living crisis and declining real-terms civil service pay. In July, the then Cabinet Office minister, Jeremy Quin, made a speech focusing on a modest number of specific initiatives he believed could make progress before the election, including opening the civil service to more digital expertise through external recruitment and secondments from the private sector. 356 Cabinet Office, ‘Skills, Efficiency and Technology in the Civil Service’, speech by Jeremy Quin MP, GOV.UK, 19 July 2023, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/speech-skills-efficiency-and-technology-in-the-civil- service Given how little time Sunak’s government has before the end of the parliament, a targeted approach to the workforce was pragmatic. To attempt another all-encompassing reform programme such as Gove’s declaration would have been implausible.

But it does mean that this parliament will end with fundamental workforce problems yet again unaddressed. And in some areas Sunak has missed opportunities to tilt the service in the right direction. His sensible abandonment of Johnson’s headcount cuts target soon gave way to a new ‘cap’ on civil service headcount and a later commitment to a reduction to pre-Covid levels. 357 Nevett J, ‘Rishi Sunak: No 91,000 target for civil service job cuts’, BBC News, 1 November 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/ news/uk-politics-63477209 358 Markson T, ‘Hunt announces civil service headcount cap’, Civil Service World, 2 October 2023, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/treasury-announces-civil-service-headcount-cap This headcount target, once again, prevents more useful workforce planning moving forward.

Civil service workforce: recommendations

The next government should make long-term workforce reforms

The next government, whatever its make-up, should seize the opportunity of having a full parliamentary term ahead of it to address these workforce problems. The necessary reforms will take time to bed in, but will help ministers deliver their policy priorities more effectively – so are worth the time and effort.

The size and total funding of the civil service are inherently political decisions for ministers to make. But to enable it to be as effective as it can be these considerations should first and foremost be shaped by what the government needs the civil service to do to develop and deliver its policy priorities – rather than by arbitrary headcount targets or short-term, superficial ‘efficiency drives’ that have proven time and again to be inefficient.

For this reason, civil service leaders and ministers should develop a strategic workforce plan at the start of each parliament, which lasts the duration of that parliament. This should forecast what resources the civil service will need to implement the government’s priorities and respond to long-term trends, including technological and demographic, and set out priorities for workforce reform. This would guard against further boom-and-bust waves of civil service recruitment and retrenchment while helping to make the service more efficient. The Civil Service People Plan 2024–2027, published earlier this month, rightly recognises the need for “improved strategic workforce planning”. 359 Government People Group, Cabinet Office, Civil Service People Plan 2024–2027, 10 January 2024, www.gov.uk/ government/publications/civil-service-people-plan-2024-2027 But doing so requires ministers and civil service leaders to be willing to address the issues that make such planning more difficult.

Reducing turnover

To reduce churn, HR directors should, where they do not already, sit on departmental boards, and permanent secretaries should be held to account for the level of turnover in their department. Certain civil servants – among the senior ranks and in the policy profession, in particular – should be employed with minimum terms of service, before which they cannot move to another civil service job except under rare circumstances. This would strengthen existing assignment duration policies, while avoiding some of the risks associated with fixed-term contracts for civil servants’ incentives to speak truth to power.

These moves must come alongside a cultural change towards turnover at the individual and department level. The recent introduction of guidance on the expected assignment duration for top roles is helpful, but will only make a difference if moving early comes with real negative reputational consequences.

Improving pay and career progression

Any workforce plan must recognise that civil service pay is straightforwardly uncompetitive with the private sector – and much of the rest of the public sector. Real terms cuts have degraded the civil service’s ability to attract and retain the best talent. Real-terms pay should rise in years to come to make it more competitive. Beyond that, departments and professions should be given greater flexibility to structure pay in a competitive manner. This is especially important for the digital, data and technology (DDaT) profession – where welcome progress has already been made – which must compete with the private sector for top digital talent.

Deeper career pathways and performance-related pay should reward officials who stay in post and accumulate expertise with higher pay. And an expert pay review body should be introduced for non-senior civil servants to bring them in line with most public services.

Composition, and location, of the workforce

The composition of the civil service workforce should change. There are too few top roles in which officials can be valued solely for their knowledge and ability, rather than their managerial capability. This damages the recruitment and retention of specialists in areas such as digital and data, and therefore the capability of the civil service. Other large organisations, like Google, Legal & General, Deloitte and the Bank of England, all offer these types of roles, and they have been previously proposed by civil service reformers, including Sir John Kingman in his 2003 capability review of the Treasury. 360 ‘Why is civil service reform so hard? Sir John Kingman in conversation with Bronwen Maddox’, Institute for Government event, 16 December 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/event/online-event/why-civil- service-reform-so-hard-sir-john-kingman-conversation-bronwen-maddox Such senior specialist roles should be piloted across departments and professions, and expanded where found to work.

The composition of the civil service should also continue to change by further progressing the civil service relocation agenda. This has been the most successful aspect of workforce reform this parliament. As our report into the Darlington Economic Campus, Settling In, 361 Urban J, Pope T and Thomas A, Lessons from the Darlington Economic Campus for civil service relocation, Institute for Government, 9 June 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/darlington-civil-service-relocation indicated, it is beginning to prove its worth by better enabling people who cannot or do not want to live in London to work for the civil service, and exposing policy makers to different experiences.

The new Civil Service People Plan described efforts to build a single platform for skills development, driven by individual-level data on the skills and experience of civil servants. 362 Government People Group, Cabinet Office, Civil Service People Plan 2024–2027, 10 January 2024, www.gov.uk/ government/publications/civil-service-people-plan-2024-2027 This is welcome and would strengthen civil service leaders’ capacity to plan and enhance the interoperability of the workforce. But it will require time, political support and resources to achieve.

Recruitment

The way the civil service recruits staff should be overhauled. The civil service interprets its need to recruit ‘on merit on the basis of fair and open competition’ in a restrictive manner that prevents hiring managers from tailoring processes in order to more fully understand candidates. A less prescribed, more decentralised approach to recruitment, on the basis of more intellectually and demographically diverse recruitment panels, would enable recruiters to do so.

Departments should be encouraged to test for expertise and knowledge for relevant roles, not just behaviours and competencies. Jobs should be externally advertised in most circumstances across government. Internal recruitment processes should change as well – hiring managers should be consistently able to see internal candidates’ previous performance appraisals. Senior leaders should also be able to secure approval to directly appoint high performers to roles that suit their skill set or will aid their development in limited circumstances. And every effort should be made to simplify administrative barriers.

Onboarding and induction processes should be much faster and more effective. Interchange should be boosted with large-scale and long-term secondment programmes with the wider public, private and third sectors, following through on the new Civil Service People Plan’s recent commitment for sector-based secondment programmes across the civil service’s professions and functions. 363 Government People Group, Cabinet Office, Civil Service People Plan 2024–2027, 10 January 2024, www.gov.uk/ government/publications/civil-service-people-plan-2024-2027 The Maude review specifically endorsed many of the Institute’s proposals in this area. 364 Cabinet Office, Independent Review of Governance and Accountability in the Civil Service: The Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham, GOV.UK, 13 November 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-governance-and- accountability/independent-review-of-governance-and-accountability-in-the-civil-service-the-rt-hon-lord- maude-of-horsham-html The same themes featured in the Declaration on Government Reform, demonstrating a broad consensus that change is needed.

Impartiality

Reform of civil service recruitment should bolster not undermine civil service impartiality. 365 Thomas A, Appointed on Merit: The value of an impartial civil service, Institute for Government, 24 May 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/civil-service-impartiality Impartiality ensures that merit – the ability to do the job well – is the defining principle on which civil servants are appointed, not patronage. This is a precious inheritance that many other countries seek to emulate. 366 Thomas A, Appointed on Merit: The value of an impartial civil service, Institute for Government, 24 May 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/civil-service-impartiality The current rules around ministerial involvement in recruitment strike broadly the right balance. Ministers have power to shape the most senior appointments, including through being consulted on the job description and selection panel, and in practice a civil servant at director level or above who does not have the confidence of their secretary of state will either not be appointed, or not last long in the job if they are. Going further would risk politicisation.

Ministers should be encouraged to participate in permanent secretary and director general appointments using the means already available to them. Departments should make ministers more aware of the opportunities they have to influence appointments as well as the proper limits to their involvement.

The centre of government

The ‘centre’ – 10 Downing Street, the Cabinet Office and Treasury – is fundamental to UK government, given its responsibility for setting much of the government’s strategic direction, ensuring the government’s priorities, policy and budgets are aligned, and holding the rest of government to account for its delivery. Alongside the prime minister, chancellor, other ministers and political appointees, the centre is comprised of many thousands of civil servants. And it is from the centre that the civil service is led, managed and organised.

So the performance of the civil service and of the centre of government are interconnected. An effective centre requires an effective civil service, and vice versa. For this reason, the Institute has over the course of the last year undertaken a Commission on the Centre of Government to assess the Cabinet Office, No.10 and the Treasury. 369 ‘Commission on the Centre of Government’, Institute for Government (no date), www.instituteforgovernment. org.uk/commission-centre-government We have held more than 10 evidence sessions and spoken to dozens of experts ranging from former prime ministers to eminent scientists, serving permanent secretaries to charity leaders.

The commission will report in February 2024. It will conclude that the centre is failing in its core purpose of supporting the prime minster to set and drive the government’s direction and holding the rest of government accountable for delivering it. The centre too often misses the opportunity to set a government’s priorities, outcomes and principles at the start of each parliament.

Structurally, No.10 and the Cabinet Office are not set up to support the prime minister as effectively as possible. There is inadequate direct, strategic and economic expertise at the prime minister’s disposal. The Cabinet Office’s purpose has become ambiguous over time, and teams at the centre compete with confused and overlapping remits.

Meanwhile, the civil service needs to be led more powerfully at the centre. The cabinet secretary and head of the civil service would benefit from clearer authority to genuinely lead and organise the institution. 370 Lilly A, Thomas A, Clyne R and Bishop M, A new statutory role for the civil service, Institute for Government, 2 March 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/new-statutory-role-civil-service

The centre of government: recommendations

When our Commission on the Centre of Government publishes its final report, we will address the problems we have identified by setting out principles for how the centre should work, and a series of proposals for how the centre could be reformed to serve its purpose more effectively.

First among those principles will be the conviction that the centre should do what can only be done at the centre of government, delegating all else. That makes its responsibility to set strategy even more crucial. So we will recommend a new approach for governments to take in setting their priorities and aligning those priorities to budgets and policy across Whitehall. We will also recommend fundamental structural changes to No.10 and the Cabinet Office to increase the strategic support available to the prime minister, clarify roles and remits between teams, and strengthen the leadership and governance of the civil service.

Civil service-ministerial relations

Relations between ministers and civil servants have been tense

Poor relations have made government less effective

Tensions between ministers and civil servants have been stark in recent years, the primary cause being criticism and active disparagement of officials from political figures. 404 Rutter J, Civil service–ministerial relations: time for a reset, Institute for Government, 19 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/civil-service-ministerial-relations The cabinet secretary himself highlighted this last year, saying: “The last five years or so have seen an increased number of overt attacks on civil servants, individually and collectively, by significant political figures.” 405 House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Oral evidence: The work of the Cabinet Office, HC 950, 12 July 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13497/pdf The Committee on Standards in Public Life (CSPL) has similarly noted “public criticism of civil servants becoming increasingly disparaging in tone”. 406 Written evidence from the Committee on Standards in Public Life (CLR04), Civil Service Leadership and Reform Inquiry, Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/ writtenevidence/122282/pdf

Political figures have used such language both within government and outside of it. Dominic Cummings 407 Johnstone R and Tolhurst A, ‘Downing Street hit list of perm secs ‘risks serious damage to the civil service’’, Civil Service World, 24 February 2020, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/downing-streethit-list-of- perm-secs-risks-serious-damage-to-the-civil-service and Jacob Rees-Mogg, 408 McGarvey E and Blake J, ‘Jacob Rees-Mogg empty desk note to civil servants insulting, says union’, BBC News, 23 April 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-61202152 for example, both took publicly antagonistic attitudes towards the civil service while in office, and Rees-Mogg sharpened his language once freed from the constraints of government. 409 Thompson S, ‘Jacob Rees-Mogg blames ‘snowflakey, work-shy’ civil servants for EU law U-turn’, The Independent, May 2023, www.independent.co.uk/tv/news/brexit-eu-law-jacob-rees-mogg-b2337529.html Regular criticism of diversity and inclusion initiatives and ‘woke’ accusations, discussed in Part 1 of this report, have also been a theme of recent years. Politicians have damaged relations in other ways, too – Sir Tom Scholar was unceremoniously dismissed as the Treasury’s permanent secretary under Liz Truss, and Dominic Raab resigned as deputy prime minister and justice secretary after being found to have bullied civil servants.

These words and actions have an impact. Civil service morale is declining, and the rate of officials leaving the service is very high. While many factors contribute to these issues, hostility from ministers and other political figures is undoubtedly one. This environment has also made it harder for civil servants to do their jobs – the cabinet secretary has said that insulting language directed at civil servants had “undoubtedly undermined the good functioning of government”. 410 House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Oral evidence: The work of the Cabinet Office, HC 950, 12 July 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13497/pdf The Covid inquiry offered a particularly striking example, with Martin Reynolds, Boris Johnson’s former principal private secretary, saying of Cummings’ alleged “sh*t list” of senior civil servants that there was:

“quite a bit of unease in the civil service around… the so-called “sh*t list” of people who were thought to be at risk… So I think it is fair to say, in the period you’re talking about, there were quite a lot of other things taking place which meant that quite a bit of senior energy and attention was focusing on other things”. 411 Evidence of the Covid-19 Inquiry, 30 October 2023, https://covid19.public-inquiry.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2023/10/30203506/2023-10-30-Module-2-Day-14-Transcript.pdf

The civil service has at times appeared to contribute to a cycle of deteriorating relations. The CSPL, 412 Written evidence from the Committee on Standards in Public Life (CLR04), Civil Service Leadership and Reform Inquiry, Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/ writtenevidence/122282/pdf for example, has noted an apparent increase in civil servants leaking to the media – which, barring exceptional circumstances, is clearly unacceptable.* There have also been troubling instances of a small number of officials in the Home Office apparently resisting agreed government policy (discussed in more detail below). This risks becoming a vicious cycle, with the result that civil servants feel unable to challenge ministers, and ministers are mistrustful of their officials. Ultimately, this would damage the quality of decision making and government effectiveness.

The impartiality of the civil service has been called into question in recent years

In addition to damaging government effectiveness, poor relations have also triggered debates around the impartiality of the civil service – concerning both whether the civil service is, in fact, impartial, and even whether the current model is desirable. Several incidents have provoked these debates.

In 2022, a small number of Home Office officials protested the Rwanda asylum scheme by pinning mocked up immigration enforcement notices targeting Paddington Bear on Home Office noticeboards. 413 Gentleman A, ‘Paddington, go home: Home Office staff pin up faked deportation notices’, The Guardian, 13 June 2022, www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/jun/13/paddington-go-home-home-office-staff-pin-up-faked- deportation-notices Leaked messages from an internal communications network also highlighted opposition to the policy, with one official posting: “Do we have a responsibility to not just leave, but to organise and resist?” 414 Syal R and Brown M, ‘Home Office staff threaten mutiny over ‘shameful’ Rwanda asylum deal’, The Guardian, 20 April 2022, www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/apr/20/home-office-staff-threaten-mutiny-over- shameful-rwanda-asylum-deal Suggestions of resisting a policy in this way are clearly inappropriate and appear to breach the civil service code. If civil servants feel unable to implement a legal** policy, having raised concerns by all appropriate means, they should resign.

But this example from the Home Office shows fault also lies on the political side. In March 2023 Conservative Campaign Headquarters emailed party members, in the name of the then home secretary, Suella Braverman, accusing “an activist blob of left-wing lawyers, civil servants and the Labour Party” of blocking the government’s efforts to stop small boat crossings. 415 Wheeler B, ‘Suella Braverman: Civil servants demand apology over small boats email’, BBC News, 8 March 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-64890882 This was an entirely inappropriate attack on civil service impartiality. Even though apologies were made, it demonstrates the traction that scepticism of civil service impartiality can gain. It also emphasises the risk of civil servants behaving in a way that feeds such scepticism.

There have been several other recent examples of politicians accusing civil servants of a lack of due impartiality. Dominic Raab accused “activist officials” of trying to block government reforms, 416 Morton B and Mason C, ‘Dominic Raab hits out at ‘activist civil servants’ after resignation’, BBC News, 22 April 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-65349192 while Jacob Rees-Mogg blamed officials for the difficulty of scrapping thousands of EU laws. 417 Chapman B, ‘Jacob Rees-Mogg slams ‘snowflaky, work-shy’ civil service as key post-Brexit measure is ditched’, GB News, 11 May 2023, www.gbnews.com/jacob-rees-mogg-civil-service-brexit-politics-latest There is no evidence for either of these contentions – yet they demonstrate how poor relations can feed such scepticism.

The furore around Sue Gray’s departure from the Cabinet Office to become Keir Starmer’s chief of staff also falls into this category. It is true that, while it is not unusual for civil servants to transition to political roles – there is ample precedent of similar moves – Gray’s seniority, prominence, sensitive government roles and the lack of an intervening period outside the civil service made this an unusual case. It is also true that the move risked damaging trust between officials and ministers. But it was wrong for some to cast doubt on Gray’s conduct as a civil servant. There has never been a serious suggestion – and certainly no evidence – from any political party that she has not behaved with due impartiality.***

A final trend in recent years has been politicians themselves risking damage to the perception of civil service impartiality via dismissals of senior officials. It is right and normal for ministers, including the prime minister, to exercise significant influence over and indeed approve the appointment of senior officials. What is less common is for several permanent secretaries to have recently left their positions, seemingly following political pressure. This risks the appearance of civil service personnel decisions being made on the basis of their alignment with ministers’ views. 418 House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution, Permanent secretaries: their appointment and removal: 17th Report of the Session 2022–23, (HL 258), 20 October 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/ publications/41636/documents/206273/default/ Even though this has not had a material effect on civil service impartiality (ultimately, career civil servants were replaced by other career civil servants), perceptions matter, and it nevertheless risks officials being less willing to give tough advice to ministers.

These controversies have had an impact, as debates around whether the civil service is, in fact, impartial moved into discussions over whether it should be. Indeed late 2022 and 2023 saw several calls for greater use of political appointments in the civil service. The former cabinet minister Liam Fox responded to the Sue Gray saga by arguing for more political control over the most senior civil service jobs. 419 Fox L, ‘As a long-serving minister I learnt just how much the Civil Service needs reform’, The Telegraph, 12 March 2023, www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2023/03/12/liam-fox-long-serving-minister-learnt-just-how-much-civil- service Lord Frost has argued that “we must find a way for the upper reaches of the civil service to reflect to a greater extent the politics of the Government”. 420 Frost D, ‘‘In Whitehall, civil servants reign over ministers’ says Lord Frost’, Conservative Post, 16 December 2022, https://conservativepost.co.uk/in-whitehall-civil-servants-reign-over-ministers-says-lord-frost The Maude review covered earlier in this report also proposed a series of radical changes in this area, 421 Cabinet Office, ‘Independent Review of Governance and Accountability in the Civil Service: The Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham’, GOV.UK, 13 November 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of- governance-and-accountability including ministers having the option of their special advisers overseeing the recruitment process for senior civil service roles, ministers being able to directly appoint a (civil service) chief of staff, and four-year fixed tenures for all senior civil servants.

Such arguments are understandable. More political appointees could, in one sense, sharpen accountability, as ministers would have more direct reports working to further their aims within their department. Such appointees could also bring fresh perspectives and more political zeal to their minister’s priorities, but the drawbacks would outweigh the benefits. 422 White H, ‘Civil service politicisation is the wrong answer to the wrong question’, Institute for Government, 3 May 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/civil-service-politicisation It would reduce the experience and expertise available to new ministers – particularly after a change in government – while weakening the principle of merit-based recruitment, and the robustness of advice available to ministers. Any minister who sought to involve themselves in a much wider range of senior recruitment would also find they were using their time inefficiently, at the expense of progressing their policy priorities.

The answer to the need for more political support for ministers, when it is felt necessary, is to increase the number of special advisers. Ministers can also appoint non-political policy advisers, should they wish to bolster particular expertise in their department. As we have long argued, there are aspects of the way the civil service works that can frustrate ministers. Part of the answer to this is to address such issues within the civil service, including through the reforms we discuss throughout this report, rather than to politicise its senior ranks.

But these debates around impartiality would probably not have arisen if the underlying relationship between ministers and officials had not become so acrimonious. In the years ahead, a reset and fundamentally reformed relationship – based on mutual respect and understanding – is also essential.

Rishi Sunak has partially stabilised relations

Lower ministerial churn in 2023 laid the foundations for more positive relations

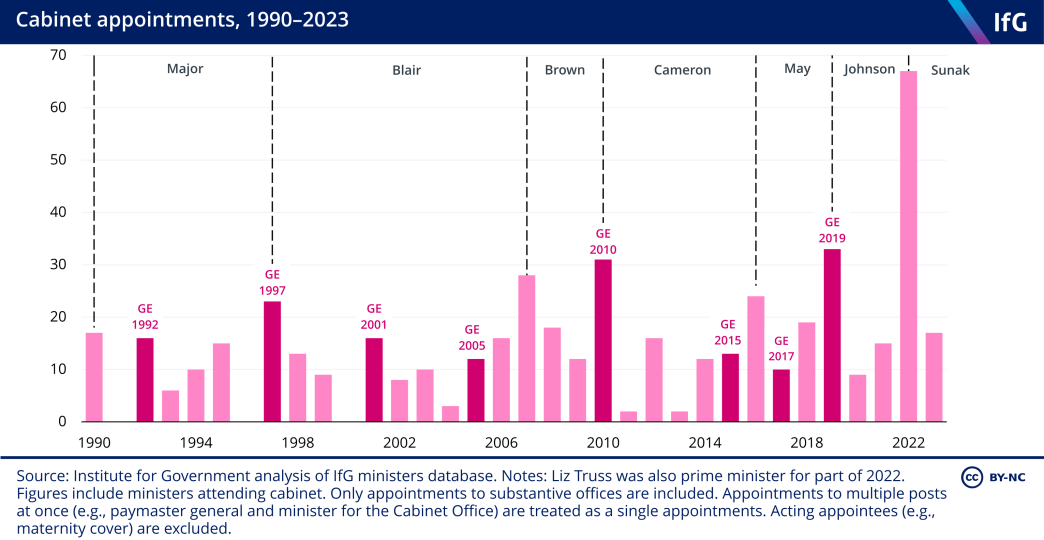

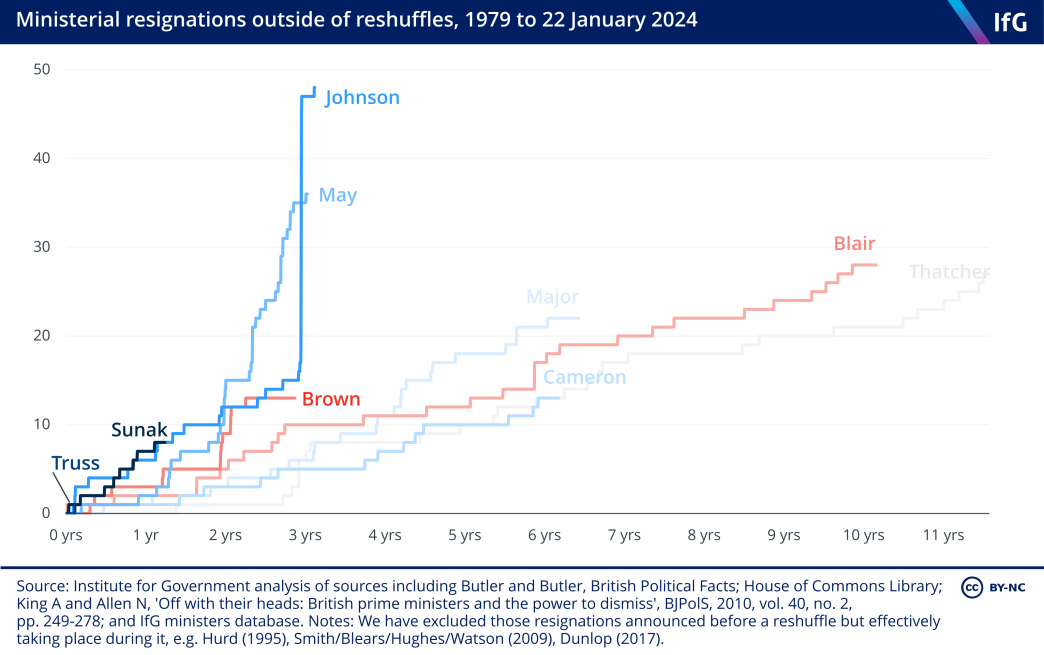

Rishi Sunak has made some progress towards building a more stable positive relationship. This is partly a result of the calmer political environment – which has, for example, translated into reduced churn in ministers. Indeed after the tumult of 2022, which saw a record 67 cabinet appointments made, there were only 17 in 2023 (see first figure below). This is still a higher than average level of annual cabinet turnover (especially outside of an election year),**** and Sunak’s first year in office saw a higher level of ministerial resignations outside of reshuffles than any of his recent predecessors’ first year in office (see second figure below).

The 17 cabinet-level changes in 2023 were partly a result of February’s machinery of government changes and the November reshuffle. A number of cabinet ministers also left government outside of reshuffles – including Ben Wallace, Dominic Raab and Nadhim Zahawi – and there were changes in the junior ministerial ranks, including those caused by the resignations of Robert Jenrick, Dehenna Davison and Lord Goldsmith.

High turnover in ministers, and particularly in secretaries of state, is not conducive to effective government or easy relations with officials. The appointment of a new secretary of state often resets departmental priorities and leads to existing policy being revisited. This is most clearly the case in policy areas given particular importance by a previous minister. For instance, when Alex Chalk replaced Raab at the Ministry of Justice, he scrapped the Bill of Rights Bill – which had been introduced to parliament a full year earlier by the Johnson government, then dropped by Liz Truss, before being re-adopted by Sunak – and reversed recent changes to the criteria for some prisoner transfers. 423 Prison Reform Trust, ‘Alex Chalk reverses Dominic Raab’s damaging changes to open conditions transfers’, 18 July 2023, accessed 31 October 2023, www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/alex-chalk-reverses-dominic-raabs- damaging-changes-to-open-conditions-transfers

Such chopping and changing can be frustrating for officials, particularly if large amounts of their work become redundant overnight.***** Lower ministerial churn is therefore welcome. If the prime minister wants to focus on delivery before the next election – and benefit from stable, positive working relations between ministers and officials – he should try to avoid disruption, including through reshuffles, in 2024.

A clear change of tone has helped

While this reduction in ministerial churn has laid the groundwork for calmer relations, also important has been an obvious shift in tone from Sunak’s government. Giving evidence to the Liaison Committee in July, for example, Sunak praised civil servants he had worked with and firmly disavowed characterisations of the civil service as a “blob”. 424 House of Commons Liaison Committee, Oral evidence: Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 1602, 4 July 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13426/pdf The cabinet secretary also strongly denounced such language. 425 House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Oral evidence: The work of the Cabinet Office, HC 950, 12 July 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13497/pdf ****** Further evidence of a shift in tone came after the November reshuffle. James Cleverly, on becoming home secretary, reportedly praised officials in an all-staff meeting, and was quoted as saying: “I will back you and I will defend you. Even when you mess up… I have no intention of briefing against officials […] I criticise in private and I praise in public.” 426 Lizzie Dearden, Tweet, 14 November 2023, https://x.com/lizziedearden/status/1724482856234209610?s=20

These are welcome developments, though there have been some less encouraging signs too. Sunak missed an opportunity to further his support for the civil service, for example, in his neutral acceptance of Raab’s resignation 427 White H, ‘Rishi Sunak’s response to Dominic Raab’s resignation won’t improve ministerial-civil service relations’, Institute for Government, 21 April 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/sunaks- response-raabs-resignation – in which he did not express a view on the reason for the deputy prime minister’s departure. The plan to cap and then cut the size of the civil service, meanwhile, is a legitimate decision for the government to have made, but one that could be inappropriately spun for political gain. And while not perhaps intended as a critique of the civil service, the measure was still announced without notice to civil service leaders. More recently, there were reports after the November reshuffle that Esther McVey, as a minister without portfolio in the Cabinet Office, could focus on tackling ‘woke’ issues in Whitehall. Such moves should not mark a return to using the civil service to make a political point – which is a particular risk as the general election approaches.

Civil service-ministerial relations: recommendations

Sunak’s premiership has so far marked a welcome easing of tensions between ministers and officials. Yet the fact that relations reached such a low point in recent years – and the reasons behind this – demonstrate why fundamental reform is necessary to clarify and strengthen the relationship.

A new, firmer statutory footing for the civil service

There is an inherent tension between ministers and civil servants in a democratic system. 428 Written evidence from the Committee on Standards in Public Life (CLR04), Civil Service Leadership and Reform Inquiry, Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/ writtenevidence/122282/pdf Ministers want to progress their priorities, which they have a mandate to deliver, while civil servants are duty bound to ensure proposals are as watertight as possible, raising inconvenient facts or challenges with implementation.

This is a necessary and at its best creative tension; for their part, ministers can test civil servants’ assumptions and bring drive, urgency and legitimacy. This relationship can only work with mutual respect and understanding. Without it, the work of government suffers. But the relationship should not be so reliant on the presence of ‘good chaps’ willing to uphold existing convention. Greater clarity is required about the respective roles and accountabilities of both ministers and officials. 429 Lilly A, Thomas A, Clyne R and Bishop M, A new statutory role for the civil service, Institute for Government, 2 March 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/new-statutory-role-civil-service The confusion and ambiguity at the heart of this relationship runs far deeper than the attitude of individual administrations or cohorts of civil servants.

The Institute has argued that, to address these and many other problems in the civil service, it is now necessary to place the institution on a firmer statutory footing. 430 Lilly A, Thomas A, Clyne R and Bishop M, A new statutory role for the civil service, Institute for Government, 2 March 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/new-statutory-role-civil-service This would clarify the responsibilities and therefore the accountabilities of the civil service, as opposed to those of ministers. It would enshrine the permanence and impartiality of the civil service, define its purposes and objectives, and create clear mechanisms for officials to be held to account for their performance. As Gordon Brown’s Commission on the UK’s Future noted in endorsing the proposal, 431 Report of the Commission on the UK’s Future, A new Britain: Renewing our democracy and rebuilding our economy, December 2022, https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Commission-on-the-UKs- Future.pdf it would also help the public feel assured as to where accountability and responsibility lie.

This would have several benefits that would help to create a more constructive relationship between ministers and officials. It would place a statutory responsibility on the head of the civil service and permanent secretaries to maintain the capability of the civil service in several areas – including standards of policy making and advice to ministers, project management, risk management and crisis response. Clearly and unambiguously making senior civil servants accountable for these tasks would effectively enshrine a stewardship function for the civil service. It would empower the civil service’s leadership with the authority to genuinely lead the institution, and the responsibility to do so.

Our recommendation for the statute to create a new Civil Service Board, chaired by a minister, would provide a means for civil servants to be properly held to account. An obligation on the board to report regularly to parliament would strengthen scrutiny

of the civil service.

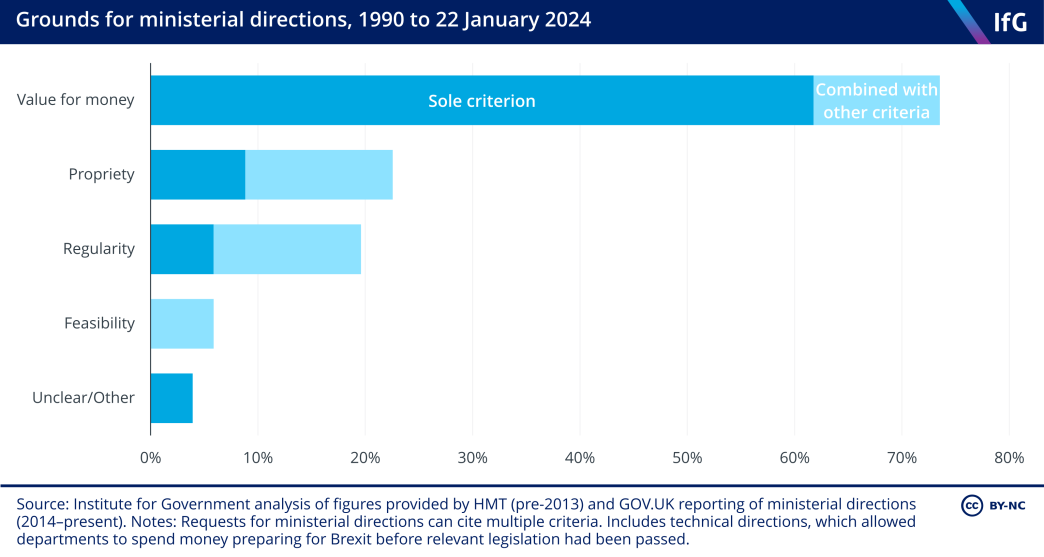

Crucially, the statutory role we envisage would not impede ministers’ rights to make policy decisions affecting the size, make up and capabilities of the civil service. Instead, we recommend a change to the criteria and use of ministerial directions.******* Were ministers to choose to pursue an action that would affect any of the capabilities that senior officials had a statutory duty to maintain, permanent secretaries should be empowered to request a ministerial direction from the secretary of state to proceed on the grounds of an expanded definition of ‘feasibility’. This would allow permanent secretaries to raise concerns when proposals may prove to be beyond the capacity of government, or when they would undermine their statutory duties to maintain the capabilities of government. 432 Lilly A, Thomas A, Clyne R and Bishop M, A new statutory role for the civil service, Institute for Government, 2 March 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/new-statutory-role-civil-service But, as with the existing system of ministerial directions, this would place accountability for the ultimate decision squarely on the relevant minister.

This would require a significant shift from the existing use and perception of ministerial directions – three quarters of which have been requested on the grounds of value for money (74%), either alone or in conjunction with another criteria. Only eight have ever been requested on feasibility grounds and then only alongside other criteria. It would also require a cultural change in the way that some ministerial directions are perceived. They should not be seen, as they sometimes are, as a sign of a policy’s failure or that the permanent secretary considers the policy to be unworkable or ‘wrong’. Directions have been used in recent years in support of policies most would deem necessary if expensive, such as the energy bill relief scheme at the height of the energy price crisis in 2022.

Reforming the governance of the civil service in this way would simplify the relationship between ministers and officials by creating a mutual understanding of who is responsible for what. The civil service would be accountable for providing a certain level of service, with the ability to shift that accountability on to ministers if their legitimate decisions made that impossible.

There have been other suggestions for how to achieve similar ends. Lord Maude, for example, agreed that “the arrangements for governance and accountability of the civil service are unclear, opaque and incomplete”. 433 Cabinet Office, ‘Independent Review of Governance and Accountability in the Civil Service: The Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham’, GOV.UK, 13 November 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of- governance-and-accountability His proposals include a formal delegation letter from the prime minister to endow the head of the civil service with the mandate and authority to run and reform the institution, and a reformed and more independent civil service commission to hold them to account. Maude also proposed that ministers should publish their objectives and permanent secretaries should make public accompanying implementation plans. He also suggested the publication of more evidence behind policies, and audits by the Civil Service Commission of the quality of advice provided to ministers.

While such reform would certainly sharpen accountability, we believe our proposed statutory solution is stronger. Maude rejected it on the basis that it could cause conflict between senior civil servants and ministers – for example, if the head of the civil service felt obliged to disobey an instruction from the prime minister if it conflicted with their statutory obligations. But this is to misunderstand our proposal. Ministers must be able to direct civil servants and override their concerns (so long as the action is legal). Our proposed reform to the system of directions would ensure that this remains the case.

Strengthening the civil service's role within the constitution

The civil service’s role as a ‘constitutional guardian’ – that is, its responsibilities to advise on, uphold and discharge aspects of the UK’s constitution – needs to be clarified and strengthened. Again, placing it on a firmer statutory footing would help achieve this. There are already elements of the civil service’s role that are constitutional in nature. The requirement for officials to act in accordance with the civil service code, for example, is effectively a constitutional principle. Some civil service roles – for instance, accounting officers – can also be thought of as fulfilling a constitutional, or at least quasi-constitutional, role.

But when it comes to advising the government on constitutional issues, or constitutional propriety, the civil service as an institution has no formally defined role. The final report of the Institute for Government’s Review of the UK Constitution, carried out jointly with Cambridge University’s Bennett Institute for Public Policy, proposed the creation of a permanent centre for constitutional expertise in the Cabinet Office. 434 Sargeant J, Coulter S, Pannell J, McKee R and Hynes M, Review of the UK Constitution: Final report, Institute for Government and Bennett Institute for Public Policy, 19 September 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/ publication/final-report-review-uk-constitution This would bring together existing constitutional advisory functions, serving as a source of advice for ministers and officials. It would help to fulfil the obligation we proposed as part of a statutory role for the civil service, for it to maintain government capability as regards “[…] advice on the constitutional and administrative responsibilities of the government”. 435 Lilly A, Thomas A, Clyne R and Bishop M, A new statutory role for the civil service, Institute for Government, 2 March 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/new-statutory-role-civil-service

We echo that review in recommending that the cabinet secretary should be able to request a ministerial direction where they are unable to assure ministers of the ‘constitutional propriety’ of their proposals. 436 Sargeant J, Coulter S, Pannell J, McKee R and Hynes M, Review of the UK Constitution: Final report, Institute for Government and Bennett Institute for Public Policy, 19 September 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/ publication/final-report-review-uk-constitution This would accompany a more formal role for the cabinet secretary as the primary constitutional adviser.

Introducing a new criterion of ‘constitutional propriety’ would allow the cabinet secretary to raise concerns publicly about ministers’ proposals without undermining the ability of ministers to make a policy decision. If, as a hypothetical example, the lord chancellor intended to respond to a court finding against the government by issuing strong criticism of the judiciary – which would clearly be constitutionally improper – this would allow senior officials to request a direction on the grounds of constitutional propriety before facilitating the lord chancellor’s plans.

Together, these proposals would strengthen the capacity of the civil service to advise ministers on constitutional issues, and to raise concerns, without undermining ministers’ ability to proceed if they so wished.

* The Institute for Government has called for improvements to routes available for whistleblowing in the civil service, and for complaints procedures, which would further reduce the circumstances in which unauthorised leaking could be legitimate.

**These protests occurred prior to the Supreme Court’s ruling on the Rwanda scheme in November 2023. The protests also targeted the merits of the policy itself, rather than discussing the potential implications of an adverse court ruling.

***What the episode did demonstrate – as the Institute argued at the time – was the need for clearer rules around civil servants’ future employment.

****Since 1990, there have been an average of 15 new cabinet appointments made in a calendar year.

*****Other changes in ministerial roles can have more surprising implications. The appointment of Lord Cameron – the first foreign secretary to serve from the House of Lords since the 1980s – was particularly notable last year. Given the procedural and cultural differences in how the Lords works compared to the House of Commons, it will have forced Foreign Office civil servants to rapidly improve their understanding of the upper house.

******Though his defence of the civil service was arguably belated – perhaps because he felt he now had the political backing necessary to give it.

*******These are the formal instructions permanent secretaries can request from their secretaries of state – in the former’s capacity as accounting officers accountable to parliament for how their department spends money – if they think a spending proposal breaches any of the criteria of regularity, propriety, value for money and feasibility.

Policy making

There is a gulf between the scale of the most intractable problems facing the UK and the policy responses of recent governments. Whether improving rates of productivity and economic growth, reducing regional inequality, meeting the public health and social care needs of an ageing and increasingly ailing population, reducing the prevalence of long-standing societal ills such as destitution and homelessness, clearing and preventing backlogs across public services, or the huge task of managing the net zero transition, successive governments’ policy has failed to keep up with the pace of change of these most pernicious problems. Unless that changes, many of them will continue to get worse.

Improving Whitehall’s policy making capability should be a joint endeavour between ministers and civil servants. Ministers should decide upon and deliver policies capable of addressing society’s long-term priorities as they see them. Civil servants should support ministers to reach effective policy decisions and implement them. Their advice should be honest, where necessary challenging, and based on the best available evidence and experience. 485 Bishop M, ‘David Davis’s frustrations with the civil service overlooks where problems really exist’, blog, Institute for Government, 10 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/david-davis- frustrations-civil-service

Short-term policy and budgets cannot address long-term problems

Most of the major problems that government faces are chronic and long-term in nature. And recent governments have shown that it is possible to make effective, long-term policy under the right circumstances. New major infrastructure like the Elizabeth Line, 15-year ‘contracts for difference’ accelerating investment in renewable energy, 486 Metcalfe S and Sasse T, The development of the UK’s offshore wind sector 2010–16, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/uk-offshore-wind-sector and long-lasting social reform such as same-sex marriage, 487 Metcalfe S and Sasse T, Proposing Change: How same-sex marriage became a government success story, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/same-sex-marriage are policies designed to survive multiple administrations and parliamentary terms. But there are many long- term policy areas, including those listed above, which governments have been unable to address. 488 Sasse T and Thomas A, Better policy making, Institute for Government, 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org. uk/publication/better-policy-making

Long-term policy making is difficult for several reasons. It is hard to build cross-party consensus in the UK, partly because of the confrontational incentives created by a first-past-the-post electoral system.* 489 Sargeant J, Pannell J, McKee R, Lilly A and Thomas A, Electoral reform and the constitution: What might a different voting system mean for the UK?, Institute for Government, 12 July 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/ publication/electoral-reform-and-constitution Ministers change roles frequently, so their focus is often skewed towards policies that can be compellingly presented and take effect in the short period they are likely to be in post. 490 Norris E, Sasse T, Durrant T and Zodgekar, K, Government reshuffles: the case for keeping ministers in post longer, Institute for Government, 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government- reshuffles-case-keeping-ministers-post-longer Even over the course of a parliamentary term, ministers are incentivised to focus more on what they can achieve before the next election than the long-term results of their policy decisions.

Governments also tend to link their fiscal rules to parliamentary terms. The failure to fully capture the impact and implications of policies over longer periods of time, and the primacy of meeting blunt ‘by year five’ fiscal rules further incentivises short-term gaming.** The budgets of Whitehall departments, local government and public services are frequently too short in scope and uncertain to provide a basis for planning long- term reforms. Capital investment, for example, is too volatile 491 Odamtten F and Smith J, Cutting the cuts: how the public sector can play its part in ending the UK’s low-investment rut, Resolution Foundation, 2023, https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/reports/cutting-the-cuts – and in any case capital budgets are frequently raided to support day-to-day spending to keep public services running (as seen in the government’s use of NHS capital budgets to plug costs of last year’s industrial action). 492 Resolution Foundation, ‘Public investment is too low and too volatile thanks to Treasury ‘fiscal fine tuning’’, press release, 30 March 2023, www.resolutionfoundation.org/press-releases/public-investment-is-too-low- and-too-volatile-thanks-to-treasury-fiscal-fine-tuning 493 Hoddinott S, ‘Forcing the NHS to reallocate capital spending is a false economy’, blog, Institute for Government, 9 November 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/nhs-capital-spending-false-economy And the Treasury has for too long prioritised short-term flexibility in the tax system over setting and achieving clear long-term objectives. 494 Tetlow G, Marshall J, Pope T, Rutter J and Sodhi S, Overcoming the barriers to tax reform, Institute for Government, 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/overcoming-barriers-tax-reform

These factors encourage ministers and officials alike to value policies capable of being planned, budgeted for, agreed and implemented immediately or within one or two years. If government is to tackle the biggest problems society expects it to address, it must overcome this chronic short-termism.

Organising policy across institutional boundaries remains arduous

As well as being long-term in nature the most pressing problems tend not to fit neatly into departmental silos. 495 Norris E, Randall J, Ilott O and Bleasdale A, Making policy stick: Tackling long-term challenges in government, Institute for Government, 2016, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/making-policy-stick Both Conservative and Labour governments have pursued cross-cutting policy priorities in recent decades, from Tony Blair’s programme to end child poverty, to Boris Johnson’s ‘levelling up’ agenda, and most recently Rishi Sunak’s economic pledges. In opposition, the Labour Party has proposed that, should it form the next government, it would pursue five cross-cutting ‘missions’.

But successive administrations have still found it difficult to manage policy programmes across departments and tiers of government. 496 Institute for Government and The Health Foundation, Cross-government coordination to improve health and reduce inequalities: summary of a private roundtable, Institute for Government, 20 July 2023, www. instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/cross-government-co-ordination-improving-health Budgets tend to be agreed bilaterally between departments and the Treasury and this means, as per the rules of Managing Public Money, that permanent secretaries, as accounting officers of their departments, are directly accountable for how most public money is spent by their department – and their department alone. 497 HM Treasury, Managing Public Money, May 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/managing-public- money Ministers are, perhaps not unsurprisingly, incentivised to focus more on those policy areas directly within their remit than those shared with or led by other ministerial colleagues.***

Cross-cutting policy priorities are most likely to thrive when the prime minister dedicates time and attention to them, as the Government Equalities Office found when it was working across departments to draft the bill introducing same-sex marriage. 498 Metcalfe S and Sasse T, Proposing Change: How same-sex marriage became a government success story, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/same-sex-marriage But the prime minister’s time is extremely limited, sometimes applied unpredictably or inconsistently, and changes with each holder of the office.

It remains a deviation from the norm for the government to prioritise setting up civil service structures to support cross-cutting policy outside departmental boundaries. It also does not do enough to learn from successful past examples of interdepartmental policy making – such as on social exclusion, the Office for Criminal Justice Reform or, more recently, preparations for Brexit. The civil service has not translated this history into a series of tools and models ministers can readily deploy in support of their priorities. Cross-cutting policy making will soon need to be the norm rather than the exception. This will require just as much change from civil servants as it will from ministers.

Too much policy neglects evidence and remains closed to outside input, despite real progress on government’s data capabilities

Over the past two decades, civil service policy making has benefited from marked improvements in government’s capabilities to collate and use data, digitise services and evaluate policies. This progress has improved the use of evidence in policy and should not be underestimated.

But too much policy remains unhelpfully closed to evidence and input, particularly from outside central government. Practical, understandable barriers often stymie comprehensive external engagement. Civil servants sometimes feel they do not have enough time to ensure outside evidence and input is fully sought, especially in contexts like the Covid-19 pandemic, which required policy at pace. 499 Tetlow G and Bartrum O, The Treasury during Covid, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/treasury-during-covid They can feel that outside evidence might point towards proposals misaligned to ministers’ priorities and so may be politically unwelcome. In energy policy, for instance, outreach to external experts has been undermined by officials being tied to a ‘house view’ that limits “what evidence is deemed relevant, what policies are considered, and who is consulted”. 500 Britchfield C and McDowall W, Evidence in energy policy making: what the UK can learn from overseas, Institute for Government, 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/evidence-energy-policy-making Or they can lack the knowledge, networks and capability to bring in that outside view. Where good practice exists, it is usually the result of the skills of particular civil servants, rather than a systematic approach of seeking external expertise. 501 Britchfield C and McDowall W, Evidence in energy policy making: what the UK can learn from overseas, Institute for Government, 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/evidence-energy-policy-making

Sometimes policy officials’ limited access to evidence reflects poor data practices. In the justice system, for example, too often the information policy makers need is not collected, not held in the right format, is poorly standardised or not shared across departments. 502 Pope T, Freeguard G and Metcalfe S, Doing data justice: Improving how data is collected, managed and used in the justice system, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/doing-data- justice

Useful analysis is also sometimes not shared across government. During the pandemic, for example, the Treasury produced its own projections for what might happen to the economy, under alternative assumptions about the disease and UK policy responses, but it did not share these widely across government, preventing other departments from fully understanding the evidence base for decision making. 503 Tetlow G and Bartrum O, The Treasury during Covid, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/treasury-during-covid

In other areas, policy can fail because it is designed contrary to available evidence. The government’s Rwanda asylum policy and wider Illegal Migration Act are the most recent, and damning, examples. The prime minister’s strategy on small boats hinges on the hypothesis that, by making the asylum system harsher and more difficult to navigate, the government can significantly deter people from crossing the English Channel. 504 Clyne R and Savur S, The Illegal Migration Bill: Seven questions for the government to answer, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/illegal-migration-bill However, the Home Office permanent secretary has confirmed on several occasions since the ministerial direction issued on this policy that there is insufficient evidence to support that assumption. 505 House of Commons Public Accounts Committee, Oral evidence: UK-Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership, HC 410, 11 December 2023, retrieved 11 January 2024, https://committees. parliament.uk/oralevidence/14018/html

The civil service also still has far to go to improve the diversity of thought and lived experience of its own officials, including by increasing socio-economic diversity. 506 Bishop M, A crossroads for diversity and inclusion in the civil service: assessing the 2022 D&I strategy, Institute for Government, 6 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/diversity-inclusion-civil- service Whitehall policy making is still too centralised and parochial, too frequently averse to genuine collaboration with front-line public services and other tiers of government. 507 Sasse T and Thomas A, Better policy making, Institute for Government, 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org. uk/publication/better-policy-making The civil service is conscious of the need to improve its ability to conduct deliberative policy making, directly working with people affected by or with experience of a policy area, but it remains behind local government in this regard.

Subject matter expertise remains a problem for civil service policy makers

Concern over the rarity of civil servants with expert policy knowledge, technical or operational expertise in a given policy area is not a new problem – it was mentioned in the 1968 Fulton report, for instance. 508 Fulton J, The Civil Service: Report of the Committee 1966-68, Cmnd 3638, The Stationery Office, 1968. The civil service has developed deep specialist expertise in some areas since then, especially over the past decade through its ‘functions’ in areas such as commercial, digital, finance and project delivery. But in policy making, civil servants are still incentivised too strongly to move quickly between roles, focusing on general policy making skills over the accumulation of subject matter expertise.

Policy making roles are varied and require a broad skill set. Civil service policy makers must be able to synthesise information, navigate different interests, advise ministers, convene experts and partners, and engage citizens. 509 Sasse T and Thomas A, Better policy making, Institute for Government, 2022 www.instituteforgovernment.org. uk/publication/better-policy-making But, in aggregate, the civil service in many policy areas does lack sufficient officials with deep subject knowledge and long-lasting, close professional relationships with stakeholders in their policy area. This can be frustrating for ministers, and restricts the quality of policy advice. As Sir David Lidington told us after four years as minister for Europe: “I would sometimes know the stuff more than [my officials] did.” 510 Ministers Reflect: Sir David Lidington, Institute for Government, 22 January 2020, www.instituteforgovernment. org.uk/ministers-reflect/person/david-lidington Similarly, a lack of specialist expertise has been identified as a priority issue in the Treasury in various reviews of the department, including the Institute’s review of its performance in the pandemic, 511 Tetlow G and Bartrum O, The Treasury during Covid, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/treasury-during-covid and an internal review of its response to the financial crisis. 512 HM Treasury, Review of HM Treasury’s Management Response to the Financial Crisis, HM Government, 2012, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7cc612ed915d63cc65cc56/review_fincrisis_ response_290312.pdf The civil service would be better equipped to advise ministers and deliver their priorities if it cultivated subject matter expertise more effectively. 513 Urban J and Thomas A, Opening Up: How to strengthen the civil service through external recruitment, Institute for Government, 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/civil-service-external-recruitment

This is difficult because civil servants are often not rewarded for developing deep subject matter expertise. As described above, high levels of civil service turnover are in part driven by a pay and career structure that, far from rewarding a progressive accumulation of expertise within a role or single policy area, encourages ambitious civil servants to move departments regularly, accumulating increasing managerial responsibilities over specific policy expertise. 514 Clyne R and Bishop M, ‘Staff turnover in the civil service’, explainer, Institute for Government, 12 April 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/staff-turnover-civil-service

There is insufficient accountability for the quality of policy advice and analysis

There is too much confusion over ministers’ and officials’ respective roles in policy making. While ministers are broadly responsible for making policy decisions, and civil servants for helping the government implement those decisions, officials are also responsible for advising ministers on policy, and ministers often make decisions about policy implementation. This ambiguity makes it difficult for government to learn lessons when policies fail.**** And it can lead to blame games and the avoidance of accountability.

This can lead ministers to express frustration at the quality of advice they receive from civil servants, and the difficulty in rectifying the problem because of unclear accountability. 515 Bishop M, ‘David Davis’s frustrations with the civil service overlooks where problems really exist’, blog, Institute for Government, 10 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/david-davis- frustrations-civil-service It can be difficult to differentiate between problems genuinely caused by poor civil service advice and those that result from political disagreements between ministers. For instance, the former Brexit secretary David Davis told us that “Whitehall did a really crap job of negotiation”, and accused officials of “running a parallel policy separate to the department” during the Brexit years. But he also acknowledged that Theresa May as prime minister played a major role in creating this situation by giving Davis’ permanent secretary – Olly Robbins – a second role as her EU sherpa, putting him in an “impossible position”. 516 Bishop M, ‘David Davis’s frustrations with the civil service overlooks where problems really exist’, blog, Institute for Government, 10 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/david-davis- frustrations-civil-service It can be difficult to judge – from parliament or otherwise outside government – the validity of frustrations with civil service advice, particularly because so much policy analysis and advice remains private.

The line between ministers’ and officials’ role in policy making will never be entirely clear. Nor should it be – it is implausible to overly formalise that core relationship at the heart of government. But ultimately a clearer delineation of responsibilities would help. And greater accountability over the quality of policy analysis and advice offered by the civil service would benefit both sides of the relationship and stand to enhance the effectiveness of policy.

Policy making: recommendations

Changes of approach could make Whitehall policy making more open, expert, long- term, intelligent and accountable. But any reforms should account for the complex and unpredictable systems in which policies are developed and iterated, 517 Hallsworth M, Parker S and Rutter J, Policy making in the real world, Institute for Government, 2011, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/policy-making-real-world as well as the full and proper role of ministers in both the outcomes and process of policy making.

Cultivate domain expertise and reduce churn

To incentivise civil servants to develop expertise in particular policy areas they must be rewarded for staying in post for longer and deepening their policy knowledge in a particular area. This will require cultural change with both ‘carrots’ and ‘sticks’. For the former, career pathways should be designed to reward those building deep specialist knowledge, so that civil servants can become more senior, with higher pay, as they become more expert in their policy area. For the latter, minimum terms of service could be used across the senior civil service and for certain policy officials, to prevent officials from moving to another job in the civil service, unless under certain specified circumstances, before they have served their time. It is welcome that the policy profession has recognised the need to address this problem, and is also considering other techniques such as secondments and expertise accreditation to make progress.

The recruitment of policy experts from outside government similarly needs to improve. New senior – and well paid – policy specialist roles should be created in every department to facilitate this. 518 Urban J and Thomas A, Opening Up: How to strengthen the civil service through external recruitment, Institute for Government, 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/civil-service-external-recruitment As covered above, external recruitment should be improved in other ways to make the process smoother for applicants, including by making job advertisements more understandable, encouraging hiring managers to test candidates for knowledge and reducing onboarding times. Large-scale secondment schemes should be established between departments and other partners in their policy sectors, to enable interchange of policy experts.

Champion robust, diverse evidence to support decision making

Policy officials already understand the importance of using diverse evidence to inform decision making. The policy profession’s standards say officials should use data, evidence and advice from a range of sources – including learning from independent analysis, outside experts, those working on the front line, and people with lived experience of the subject area – to understand the “diverse needs of those affected” by policy and, ultimately, design policy well. 519 Policy Profession, Policy Profession Standards, GOV.UK, 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/6246c65dd3bf7f32a7c011c7/UPDATED_PP_Standards_main_v5_acc.pdf But, as established above, there are often practical barriers to achieving these standards – whether civil servants’ lack of time, feelings that external expertise might not align with ministerial priorities, or lack of the knowledge, networks and capability to bring in an outside view.

The policy profession cannot police these standards of policy making alone. It requires ministers and senior civil servants in each department to expect policy proposals, wherever possible, to be informed by the best available evidence and input. Clarifying accountability for policy advice, and publishing more of it (see below), would help. But ultimately if ministers and senior officials want high-quality advice, they need to hold their teams accountable for the evidence base underpinning advice, and they need to want to engage with that evidence.

Hold civil servants accountable for the quality of their advice

There are several ways in which the accountability of the civil service for policy making can be clarified and strengthened. This report, above, explains the Institute’s recommendation for placing the civil service on a new statutory footing and, in doing so, endowing the head of the civil service and permanent secretaries with a statutory responsibility for maintaining the capability of government in a number of areas, including the provision of policy advice. This would make more explicit the civil service’s responsibility to ensure it is able to provide top quality, consistent policy advice to ministers.

This accountability could be enacted via a new oversight board for the civil service. If ministers felt the civil service was failing to undertake its duty to provide high quality advice, they could use this board as a means of holding the civil service to account and rectifying the problem. On the other hand, if permanent secretaries believed that ministerial decisions jeopardised their duty to maintain policy making capability, they would be able to seek resolution themselves through the board, ultimately using a ministerial direction on the grounds described above if necessary.