Disputes under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement

The UK–EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement has a mechanism for settling disputes. But how does it work?

What does the Trade and Cooperation Agreement say about disputes?

Like many international trade agreements, the UK–EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) has a mechanism for settling disputes. This allows either side to challenge the other if they believe that the other side is not upholding its commitments.

Why would a dispute arise under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement?

There are different reasons disputes could arise under the TCA, including:

- One side breaks the terms of the agreement: for instance, by imposing a tariff on goods originating in the other party,[1] or by cutting fishing boats’ access to waters below agreed levels.

- One side is unable to implement the agreement: perhaps because they require action by a regional or local government that the EU or UK governments are unable to enforce.

TCA: main dispute settlement mechanism | TCA: other dispute settlement mechanisms

The two sides interpret the agreement differently: For example, under Article [GOODS.10], there are restrictions on the circumstances under which each side can ban imports from or exports to the other. The UK government has indicated that it would like to ban the import of foie gras and the export of live animals on the grounds of animal welfare, which might not be compatible with the TCA.

When does the main dispute settlement mechanism apply?

Most of the agreement is subject to the main dispute settlement mechanism (DSM), but some of it is explicitly excluded.

In some cases, this is because parts of the TCA have alternative DSMs. For example, the section dealing with law enforcement and co-operation in criminal justice has its own bespoke mechanism.

In other cases, no alternative mechanism is provided. This means that if a party breaches the agreement – even knowingly or deliberately – the only option is for the other party to raise the issue at political or diplomatic level. Many of these cases cover sensitive issues such as taxation, where both sides have sought to maintain maximum autonomy over future policy so have avoided making commitments to which they could be held.

How does the main dispute resolution procedure work?

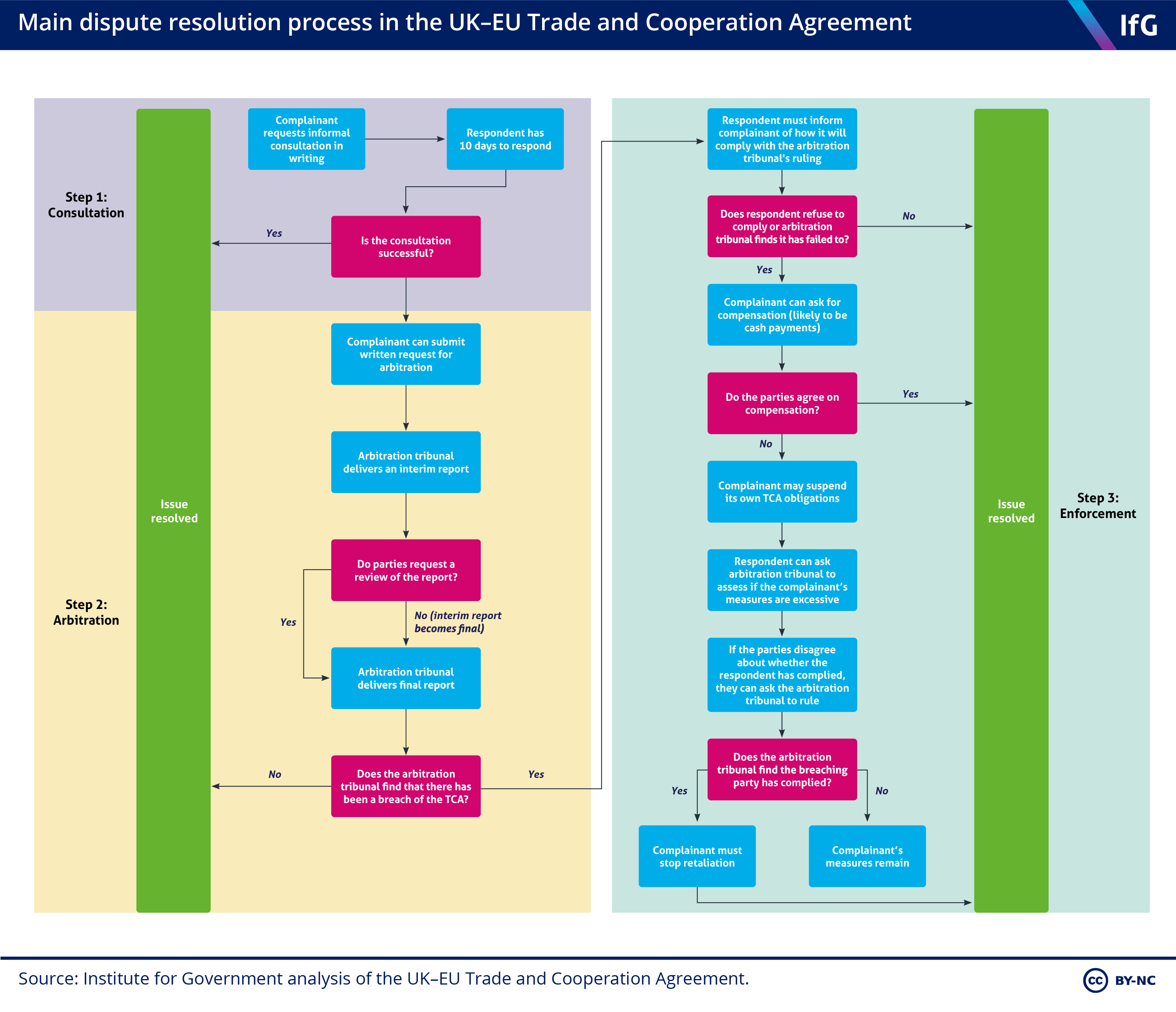

The main DSM has three stages: consultations, arbitration and enforcement.

Step One: Consultation

This consists of informal consultations between the parties. These must be requested in writing by the complainant, and once the request has been received the respondent has 10 days to reply. The consultations must be held within 30 days of the request, or 20 days in urgent cases. They can usually take place through a meeting of the UK–EU Partnership Council or one of its sub-committees.

Step Two: Arbitration

If consultations do not succeed, the complainant can submit a written request to start arbitration. Within 10 days of this request, the two sides have to agree on who is to sit on the arbitration tribunal.

Each arbitration tribunal is composed of three members selected from a list of potential arbitrators previously agreed by the UK and EU. One will come from a list proposed by the UK, one from a list proposed by the EU, and one from a list of potential chairs who must not be citizens of either the UK or the EU. Regardless of their nationality, all three arbitrators must act independently and have “demonstrated expertise in law and international trade”.

The tribunal is required to deliver an interim report within 100 days of the arbitration starting.[2] The two sides then have 14 days to request a review of any aspect of the interim report. If neither side submits such a request, the interim report automatically becomes the final ruling of the tribunal. If they do request a review, the tribunal will deliver its final ruling within 130 days of the start of the arbitration (halved in urgent cases). The tribunal can delay delivery of its interim report or final ruling for up to 30 days if it cannot complete the work in time.

It can take over 160 days from the complainant raising a dispute to the arbitration tribunal making its final ruling. This is quicker than the dispute resolution processes found in other international agreements (including the UK–EU Withdrawal Agreement and WTO rules), which regularly take over two years to conclude a dispute and have sometimes taken over a decade (for example, the EU–US dispute over beef hormones).

There is no appeal from the tribunal’s final ruling.

Step three: Enforcement

If the tribunal finds that there has been a breach of the agreement, the respondent has 30 days to inform the complainant of the measures it will take to comply. If it cannot comply immediately, it must agree a reasonable period of time to do so with the complainant. If they cannot agree, the original arbitration tribunal can determine the period of time.

The complainant party can ask the respondent for temporary compensation if it refuses to comply; if it fails to notify the complainant party of the measures it will take before the deadline; or if the tribunal finds that it has failed to comply with its ruling. (This would likely take the form of cash payments, although this is not made explicit in the text of the TCA.) The respondent must then make a proposal for appropriate temporary compensation and try to agree it with the complainant within 20 days.

If they cannot agree (or if the complainant does not want temporary compensation), the complainant can retaliate by suspending its own obligations under the agreement. This means that it would stop applying parts of the agreement that benefit the trade of the party breaching the agreement (and can include cross-retaliation to other parts of the agreement). This would probably take the form of imposing tariffs on the breaching party’s exports. Any retaliation cannot exceed the amount of harm caused by the initial breach. If the respondent believes that the retaliation proposed is excessive, it can ask the original arbitration tribunal to make a ruling on it.

Even after retaliation has started, the respondent can inform the complainant party that it has begun to comply. The complainant must then stop its retaliation within 30 days unless it disagrees with the party in breach. In that case, the original arbitration tribunal can decide on whether the respondent is now complying.

What other dispute settlement mechanisms exist under the TCA?

The level playing field

The main alternative DSM in the TCA falls under the section dealing with the ‘level playing field’ and covers areas such as labour and environmental standards.

If one party believes the other side is not complying with its obligations in these areas, it can refer the dispute to consultations and arbitration by a panel of experts. If the panel of experts find that a party has breached the agreement, the parties will discuss what measures should be taken to address the breach. If the two sides disagree, they can ask the panel to provide recommendations. Unlike the main DSM, the breaching party does not have to abide by recommendations of the panel of experts. However, if it doesn’t abide by the recommendations and the issue relates to breaches of the labour or environment provisions, the complaining party may be able to take temporary remedial measures – such as suspending some of its obligations under the agreement.

The TCA also involves a ‘rebalancing mechanism’ designed to deal with significant divergence in the parties environmental and labour standards over time. If a party believes “material impacts on trade or investment between the Parties are arising as a result of significant divergences between the Parties” in the fields of environment or labour standards may take “appropriate rebalancing measures”. Like the “suspension of obligations” provided for under the main DSM, these might also take the form of new tariffs on the other side’s exports.

To use the rebalancing measures, the party must notify the Partnership Council and consult with the other party for 14 days. Following that 14-day period, the party against which the rebalancing measures are to be taken then has five days in which it can ask to refer the measures to arbitration. If it does, an arbitration tribunal will be convened following the same rules as the main DSM and will have 30 days to make a ruling on whether the rebalancing measures are justified. During those 30 days, the measures may not be applied.

A party can use the rebalancing mechanism even if the other side has not breached the level playing field provisions. For example, if the UK were to raise its environmental standards unilaterally in a way that created a significant divergence with EU standards and created a material impacts on UK–EU trade, the UK could take rebalancing measures against the EU. It would not matter that the divergence had been caused by the UK’s own decision to raise its standards or that the EU was compliant with the TCA.

Fisheries

In addition, there is a separate DSM for fisheries issues. The main difference with the main DSM is that, where fish are concerned, the complaining party can retaliate with seven days’ notice before arbitration has taken place. These retaliatory measures can include suspending access to fishing waters, imposing tariffs on fish products or other goods, and possibly even suspending the trade and level playing field provisions of the TCA.[3]

Any measures taken must be commensurate to the economic and societal impact of the alleged breach (in practice, this means it is highly unlikely that suspending large parts of the TCA would be deemed commensurate to a breach of fishing rights). The complainant must also launch an arbitration process under the normal dispute resolution procedure.

Is the TCA dispute settlement mechanism likely to be used much?

This is not yet clear.

On the EU side it is the European Commission (not individual member states) that triggers dispute settlement or retaliation, although it must discuss matters with member states in the Council of the EU and ’take the utmost account’ of their comments.

While most EU trade agreements contain arbitration provisions, until 2019 it had never made use of any of them. This is similar to the behaviour of most international trading powers, which have generally preferred to use the WTO dispute settlement mechanism even where a bilateral one is available.

Since 2019, however, the EU has launched four bilateral arbitration processes (against South Korea, Ukraine, the Southern African Customs Union and Algeria). In addition, EU officials have suggested that they will be vigilant in making sure the UK does not acquire an unfair competitive advantage. This means the mechanism may be used more frequently than the EU has used similar systems in the past.

The UK government has suggested it could raise a dispute under the TCA if France goes ahead with sanctions against UK fishing vessels. These sanctions have been threatened because of French claims that the UK and Jersey have failed to grant licenses to French fishing vessels, in breach of the TCA.

How does the TCA’s dispute settlement mechanism link to the Withdrawal Agreement?

The TCA allows some of its provisions to be suspended if a party does not comply with an arbitration ruling made under ‘an earlier agreement’ between the UK and EU, which includes the Withdrawal Agreement.[4]

The Withdrawal Agreement says that non-compliance with an arbitration ruling under the Withdrawal Agreement dispute settlement mechanism can result in parts of the Withdrawal Agreement “or any other agreement between the UK and the EU” being suspended “under the conditions set out in that agreement”. This includes the TCA.[5]

In March 2021, the EU launched legal proceedings (which have since been suspended) against the UK under the Withdrawal Agreement in relation to the UK’s failure to fully implement the Northern Ireland protocol. In doing so, it said that in the case of continued non-compliance by the UK, it could seek to suspend its obligations under the TCA.[6]

Can the TCA be suspended or terminated without a dispute?

The TCA contains provision that allow either party to suspend or terminate all or part of the agreement without the other party being at fault.

The entire TCA can be terminated with 12 months’ notice. Parts of the agreement can also be suspended or terminated, subject to specific notice periods and processes.[7] For example, most of part two (covering topics such as trade, aviation, road haulage and fisheries) can be suspended or terminated with nine months’ notice.

A party may suspend or terminate all or parts of the TCA with just 30 days’ notice if it believes the other has committed a ‘serious an substantial failure’ to adhere to the ‘essential elements’ of the (which includes ‘democracy’ and the ‘rule of law and human rights’). Any measures taken in these circumstances must be proportionate and in compliance with international law (including the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties).

- As the UK did in 1964 to its partners in the European Free Trade Agreement.

- This is defined as the date on which the last of the three arbitrators to accept their appointment does so.

- The ability to suspend the trade and level playing field parts of the TCA does not apply to fisheries disputes relating to Guernsey, Jersey or the Isle of Man.

- UK–EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement, Article 178(2)(b)

- Withdrawal Agreement, Article 178(2)(b); House of Commons Library, The UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement: governance and dispute settlement.

- European Commission, Withdrawal Agreement: Commission sends letter of formal notice to the United Kingdom for breach of its obligations under the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland, 15 March 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_1132

- Fella S, The UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement: governance and dispute settlement, House of Commons Library Briefing, 3 August 2021, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9139/CBP-9139.pdf

- Topic

- Brexit

- Keywords

- Trade Northern Ireland protocol

- Country (international)

- European Union

- Publisher

- Institute for Government