Government ministers

This explainer sets out what are the different types of ministers, how they are appointed and what they do.

What are the different types of minister?

The most senior government ministers, except the prime minister, are secretaries of state. Some senior ministers carry different titles, including the chancellor of the exchequer – the senior minister at HM Treasury – and the lord chancellor, though the latter has in recent years been held in conjunction with the secretary of state for justice.

Beneath secretaries of state are two ranks of junior ministers: ministers of state and parliamentary secretaries (often known as parliamentary under secretaries). While ministers of state are politically senior to parliamentary secretaries, they are constitutionally similar and the responsibilities of both are delegated from the secretary of state.

Most junior ministers are given a title to signal both their policy responsibility in a department and the government’s policy priorities – such as the minister of state for crime, policing and fire in the Home Office and the parliamentary under secretary of state for tech and the digital economy in the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.

Whips are also ministerial positions but serve different functions to senior and junior ministers. Parliamentary private secretaries are not ministers of the government. They act as unpaid departmental assistants to ministers, being the eyes and ears of the minister in parliament and communicating with the backbenches. They are required to vote with the government.

How are ministers appointed?

Ministers are ceremonially appointed by the King, on the advice of the prime minister. The allocation and organisation of portfolios for secretaries of state is decided by the prime minister, and is published online. Ministers can be chosen from either the House of Commons or the House of Lords.

Some ministers, including secretaries of state, receive seals of office from the King. A very few others have their appointments made or confirmed by Letters Patent or Royal Warrant. In these cases, the appointment process is completed with the delivery of the seals.

Ministers are chosen for a range of reasons – as a reward, to build allies, to signal a shift in policy or, sometimes, on assessment of objective performance. The appointment process for junior ministers has been criticised as “random and arbitrary”.

Sometimes prime ministers make changes to the structure of government departments. This can change the portfolio of ministers, even in departments which do not change. For instance, after Theresa May’s departmental restructuring in 2016, skills, higher education and the apprenticeship levy were brought into the Department for Education, making the secretary of state for education responsible for policy areas previously outside of their control.

How many ministers are there?

The legal maximum number of paid ministers is 109, including the prime minister, as set out in the Ministerial and other Salaries Act 1975. However, the government can appoint more ministers if they remain unpaid. The House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975 caps the number of ministers that can sit in the House of Commons at one time at 95. Since 2021 it has been possible for ministers to take paid maternity leave, at the Prime Minister's discretion. While doing so, they are designated as a "minister on leave" and do not count towards these numerical limits.

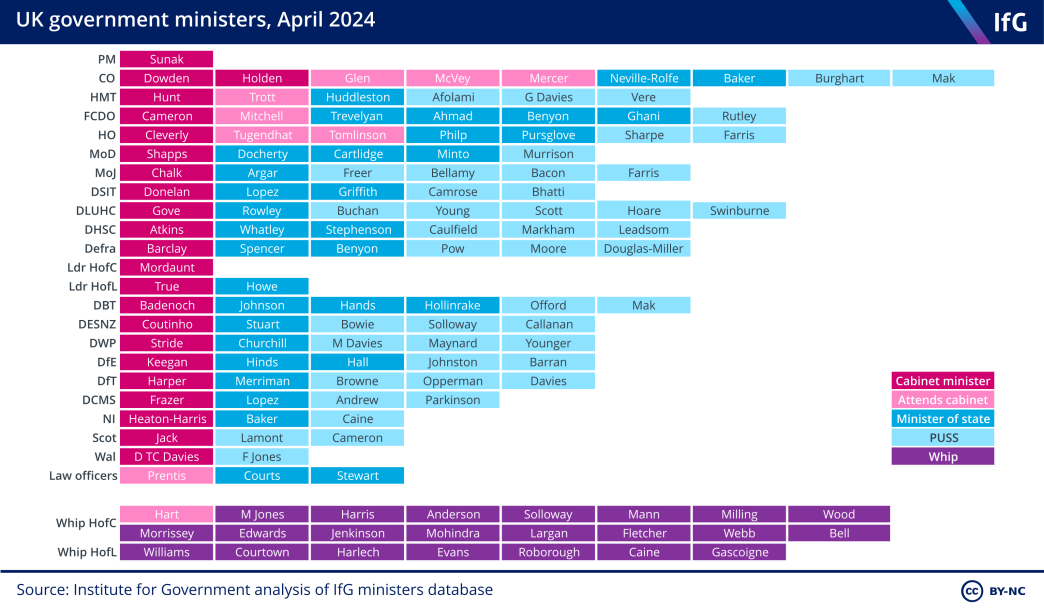

As of April 2024, there are 143 ministerial posts, held by 125 people. Some individuals hold multiple posts, like Maria Caulfield, who is both minister for women and minister for mental health and women’s health strategy.

108 ministers are currently paid (including Baroness Penn, who is on maternity leave) and 18 are unpaid. Under the Ministerial and other Salaries Act 1975, ministers can only receive one government salary – if they hold two posts, at least one of them will be in an unpaid capacity. For example, Amanda Solloway is both a parliamentary under-secretary and a government whip, and is only paid as a whip. Some ministers are unpaid even though they only hold one post – for example, Baroness Neville-Rolfe, a minister of state in the Cabinet Office.

Typically, one Conservative cabinet minister – the party chair – is an unpaid minister without portfolio who receives a salary from the party rather than the government. This post is currently held by Richard Holden.

What do cabinet ministers do?

Secretaries of state are responsible for leading departments, approving key decisions, developing policy objectives and monitoring their progress. As Caroline Spelman, former secretary of state for the environment put it, “the secretary of state carries all the responsibility. It is no good blaming other people for something that goes wrong”. Former home secretary Amber Rudd echoed a similar sentiment, saying "the mistakes that the government had made, and that the Home Office had made, required the resignation of the home secretary, irrespective of my own mistakes".

Beyond their policy work, cabinet ministers are also expected to answer questions in parliament and in front of select committees, take legislation through parliament, build relationships with backbenchers, and negotiate with other parts of government.

While most ministers will work in government departments, there can also be a minister without portfolio, who will not work in a government department but is often responsible for a specific priority. Baroness Warsi, for instance, was given responsibility across multiple policy areas, like foreign policy and constitutional affairs.

Some ministerial titles – such as lord privy seal or the chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster – relate to historical roles. The posts are largely ceremonial, and ministers appointed to these titles will normally be given a wider portfolio of work such as being leader of the House of Lords or minister for the Cabinet Office.

What do junior ministers do?

The roles of ministers of state and parliamentary secretaries can vary depending on the size of the department, but often considerably more responsibility is delegated to ministers of state. This is at the discretion of the secretary of state. As well as their direct policy responsibilities, a lot of the work of junior ministers is “unglamorous” and “an awful lot of the routine stuff, the nuts and bolts”, as Robert Neil, a former minister for local government described it. This involves dealing with correspondence, taking questions in and guiding bills through parliament.

Many government departments have a minister in the House of Lords who represents the government in the upper House to guide legislation through that chamber. Beyond this legislative work, ministers are also expected to maintain relationships with public bodies and external organisations.

Junior ministers may also attend cabinet at the invitation of the prime minister. The attendance of some is a long standing convention, like the attorney general – who advises cabinet on legal matters – or the chief secretary to the Treasury – who oversees departmental spending. Others may be chosen to attend because their portfolios reflect the prime minister’s priorities. For instance, minister for illegal immigration Michael Tomlinson currently attends cabinet, reflecting the importance of immigration as a key priority for Rishi Sunak.

What do joint ministers do?

Some junior ministers are joint ministers, working across two or more departments. Before their merger in September 2020, the Foreign Office and the Department for International Development had an entirely joint junior ministerial team. There are currently two joint ministers across government, significantly fewer than in recent governments.

These jobs can allow ministers to break down any divides that exist between different parts of government. As a minister Jo Swinson was responsible for equalities policy, holding positions in both the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. She said that double-hatting helped “in preventing the silo mentality”.

However, other ministers working across two departments have found that it adds to the difficulty of the job. Damian Green, who worked as a junior minister in both the Home Office and Ministry of Justice during the coalition, said that “most of all you are trying to work to two bosses who may well have two different agendas, and indeed there is an inherent tension between the home secretary and the justice secretary whoever it is.” Sam Gyimah – a joint minister across the Cabinet Office and Department for Education (also during the coalition) – spoke of the “challenges” of having two separate “briefs that were incompatible”.

How are government ministers held accountable?

Secretaries of state are accountable to parliament for how the powers of their department are exercised, for instance by answering questions in the chamber or appearing in front of select committees.

Junior ministers are also responsible to parliament, but ultimate accountability lies with their secretary of state. All ministers serve at the discretion of the prime minister and can be dismissed or reshuffled for any reason.

Ministers of all ranks are bound by collective responsibility – meaning that once the government has decided a collective position, all ministers must abide by it and vote together. Ministers who cannot abide by this are expected to resign, as a number of Theresa May’s ministers did in 2018 due to their opposition to her Brexit deal. Ministers who vote against the government would normally be sacked or asked to resign.

The general expectations of the conduct of ministers are in the ministerial code. A breach of the code can be investigated at the discretion of the prime minister. Any subsequent demand for resignation is also at the discretion of the prime minister. A 2020 investigation concluded that home secretary Priti Patel had breached the code because it found evidence that she had bullied staff. However, then prime minister Boris Johnson did not ask her to resign.

- Topic

- Ministers

- Position

- Cabinet secretary Foreign secretary Health secretary Home secretary Secretary of state Minister of state Parliamentary under secretary of state

- Publisher

- Institute for Government