Stormont Brake: The Windsor Framework

What is the Stormont Brake and why has it been agreed?

What is the Stormont Brake and why has it been agreed?

The Stormont Brake is a mechanism that gives the Northern Ireland assembly the power to object to changes to EU rules that apply in Northern Ireland. It was agreed as part of the Windsor Framework, the UK–EU agreement that changed the Ireland/Northern Ireland protocol.

The protocol, as originally agreed, required Northern Ireland to stay ‘dynamically aligned’ with EU law in a range of areas including agriculture, the environment, product regulation and VAT. The annexes of the protocol listed over 300 EU acts, and the protocol stated that any changes or amendments to those acts would apply automatically. New acts can also be added to the annexes if agreed in the UK-EU Joint Committee.

However, several parties including the UK government, unionist parties and the House of Lords Northern Ireland Protocol Committee raised concerns about the ‘democratic deficit’ whereby laws apply to Northern Ireland without them having any representation in the policy making process. To address this, the UK and EU agreed on the ‘Stormont Brake’ to allow Northern Ireland politicians to raise concerns about specific changes to EU law.

When and how can the Stormont Brake be triggered?

The Stormont Brake applies to amendments or updates to EU law that apply in Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework, rather than new acts.

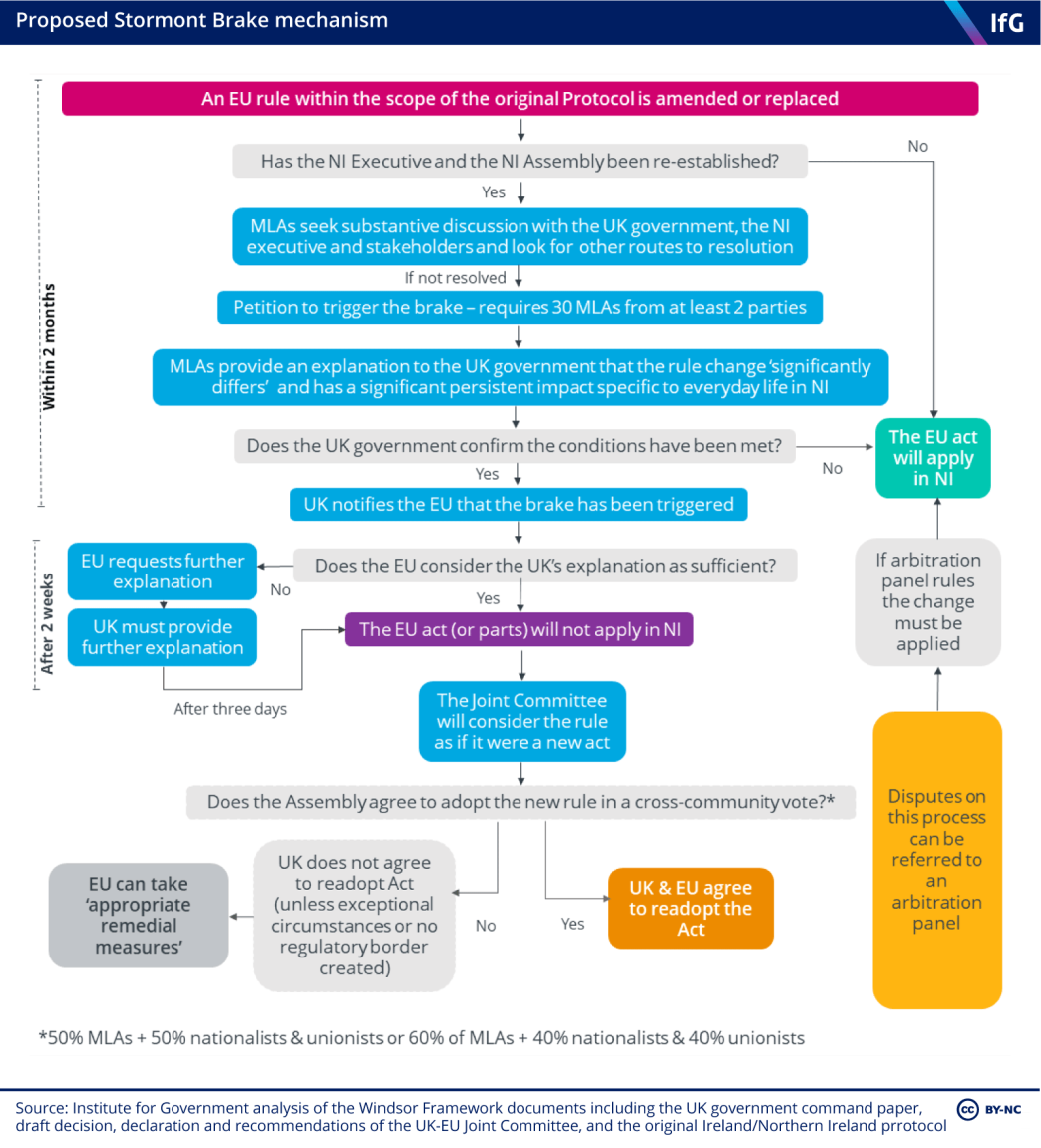

The brake can be triggered by 30 MLAs from two political parties, which is the same threshold as a petition of concern (the special mechanism for requiring cross-community consent). MLAs must explain that they have met a number of conditions before the brake can be triggered:

- The brake should only be used in the “most exceptional circumstances and as a last resort, having used every other mechanism”.

- MLAs must first seek substantive discussion with the UK government, the Northern Ireland executive and relevant business and civil society stakeholders, and look for other routes to resolution.

- The content or scope of the change “significantly differs” from the original rule and would have a “significant impact specific to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland” in a way that is liable to persist.

Once the Stormont Brake is triggered, the UK government must judge the MLAs’ explanation that the brake has been triggered appropriately. If it does not confirm that three conditions have been met, the EU act will apply in Northern Ireland.

What happens once the Stormont Brake is triggered?

The UK has two months from the publication of the EU act to notify the EU that the brake has been triggered, which means the process set out above must take place within this time period. The UK must provide a detailed explanation of how the act “significantly differs” and would have a “significant impact” on everyday life (as is the condition required in point three).

Once this process has taken place, the EU act will be suspended within two weeks – unless the EU does not consider the UK’s explanation as sufficient and request further explanation. In this case, the UK must provide this within two weeks. Once provided the EU act will be suspended within three days.

At this point, the UK and EU will consider the EU act as if it were a completely new rule that the EU was proposing to add to the protocol/framework (rather than an amendment or update to an existing rule). The Joint Committee – the UK–EU body responsible for overseeing the Withdrawal Agreement – is required to discuss the act in question, and once the committee has concluded these discussions the UK government must decide whether to agree to re-adopt the act or not.

The UK government must not agree to adopt the act unless the Northern Ireland assembly has passed an ‘applicability motion’ – supporting the rule being added – with cross-community support. This means 50% of MLAs made up of 50% of nationalists and 50% of unionists, or 60% of MLAs made up of 40% of nationalists and 40% of unionists. However, the UK government can bypass this requirement if it judges there to be "exceptional circumstances" – which includes the assembly and executive not being operational – or if the EU act would not create a regulatory border, meaning that it would not divert trade or impair the flow of goods.

If the UK decides not to adopt an EU act, the Joint Committee must examine other possibilities and the EU can take “appropriate remedial measures”, which could include measures to address the fact that Northern Ireland goods may no long fully comply with EU law.

Can the brake be used when the executive is not sitting?

The UK government has stated that the brake cannot be used until the Northern Ireland executive had been restored, and the assembly is sitting regularly.

However, in the event of future collapses the brake can be used if the MLAs wishing to trigger it are “individually and collectively seeking in good faith to fully operate the institutions”. 16 Explanatory memorandum to The Windsor Framework (Democratic Scrutiny) Regulations 2023, www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2023/9780348246322/memorandum/contents This is intended to prevent one party from collapsing the executive to prevent the brake from being used by other parties.

What happens if the UK and EU disagree about how it has been used?

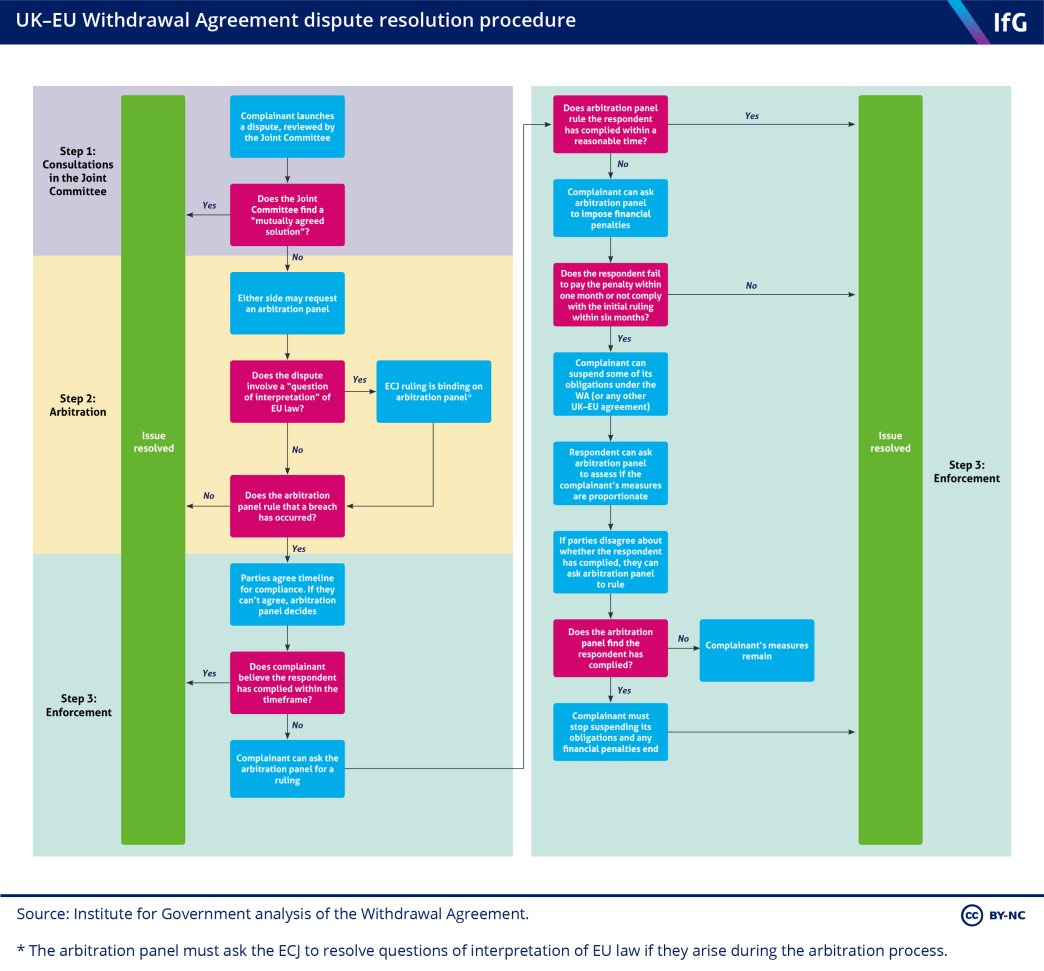

If either the UK or the EU disagrees about the use of the Stormont Brake or associated actions, such as the use of remedial measures, then they can launch a dispute under the existing Withdrawal Agreement dispute resolution procedure. If the matter cannot be resolved by the Joint Committee, it will be referred to an arbitration panel comprised of members nominated by the UK and the EU. The panel must try to reach a decision within 12 months, at which point the ruling the parties must comply or be liable to financial penalties.

As part of the Windsor Framework, the UK and EU have agreed that if the arbitration panel rules that the UK has not acted in good faith in using the Stormont Brake, or the conditions that the rule change ‘significantly differ’ from the original rule, and has a ‘significant impact’ on everyday life have not been met, then the EU rule will apply from the first day of the second month after the ruling.

What do the political parties say about the Stormont Brake?

The Democratic Unionist Party leader Sir Jeffrey Donaldson has said the Stormont Brake appears to give the Northern Ireland assembly the ability to curb the application of EU law where it affects Northern Ireland's ability to trade with the rest of the UK. 17 Ravikumar S, ‘Northern Ireland’s DUP: New deal does give Stormont ability to apply brake’, Reuters, 28 February 2023, www.reuters.com/world/uk/northern-irelands-dup-new-deal-does-give-stormont-ability-apply-brake-2023-02-28/ But the party’s chief whip Sammy Wilson has described the brake as merely a “delaying mechanism” and highlighted that the UK government, not Northern Ireland politicians, has a final say in notifying the EU. 18 Bond D, ‘Unionists voice “concerns” over Rishi Sunak’s post-Brexit Northern Ireland trade deal’, Evening Standard, 1 March 2023, www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/windsor-framework-deal-northern-ireland-brexit-rishi-sunak-eu-unionists-b1063913.html

The SDLP has expressed concerns about potential “vexatious use” of the Stormont Brake damaging access to the single market. 19 House of Commons, Hansard, ‘Northern Ireland Protocol’, 27 February 2023, col. 593 The Alliance Party has similarly suggested that the brake may add more instability into the Northern Ireland assembly. 20 House of Commons, Hansard, ‘Northern Ireland Protocol’, 27 February 2023, col. 587 SDLP and Alliance Party MPs voted in favour of the legislation implementing the Stormont Brake, and the DUP voted against. However, the government also said this vote would be used to allow MPs to express their support of or opposition to the Windsor Framework as a whole.

- Topic

- Brexit

- Keywords

- Northern Ireland protocol Withdrawal Agreement Intergovernmental relations Internal market Trade The union

- Country (international)

- European Union

- United Kingdom

- Northern Ireland

- Political party

- Democratic Unionist Party

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Devolved administration

- Northern Ireland executive

- Legislature

- Northern Ireland assembly

- Publisher

- Institute for Government