Sewel convention

How the Sewel convention works in practice and what happens when devolved consent is withheld.

What is the Sewel (legislative consent) convention?

Devolution to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland does not formally alter the principle of parliamentary sovereignty, meaning that the UK parliament is able to pass legislation for all parts of the UK, including in relation to devolved policy areas.

However, since 1999 the UK government has followed a convention, known as the Sewel convention, that the UK parliament “will not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters without the consent” of the devolved legislatures, meaning the Scottish parliament, Welsh parliament (Senedd Cymru) and Northern Ireland assembly.

The convention applies when UK legislation:

- changes the law in a devolved area of competence

- alters the legislative competence of a devolved legislature

- alters the executive competence of devolved ministers or departments.

How does the Sewel convention work in practice?

When the UK government plans to introduce a bill with provisions that fall within the scope of the Sewel convention, it is expected to consult with the devolved administrations early in the process, to ensure that devolved views are taken into account.

After a bill of this type is introduced in parliament, the devolved administrations publish a legislative consent memorandum, as required by the standing orders of the devolved legislatures in Cardiff, Edinburgh and Belfast.

The legislative consent memorandum sets out the bill’s objectives, the reasons why consent is required, and usually indicates whether and why the devolved government believes consent should be given.

Before a bill reaches its final amending stage in the UK parliament, the devolved legislatures then vote on a legislative consent motion to either grant or withhold consent for the bill, in part or in full. If consent is not granted, the UK parliament can decide whether to amend the bill to meet the devolved concerns, or to pass the legislation as it stands.

What happens when devolved consent is withheld?

The Sewel convention is not legally binding. It was put into law in the Scotland Act 2016 and the Wales Act 2017. But although these acts “recognise” the existence of the convention, they do not limit the power of the UK parliament to legislate on all matters for all parts of the UK.

The Supreme Court ruled, in 2017, that since the Sewel convention remains just a political convention, “policing the scope and manner of its operation does not lie within the constitutional remit of the judiciary”. This means the devolved governments cannot turn to the courts to enforce the legislative consent convention.

As a result, the UK parliament can pass bills without devolved consent, even when the UK government accepts that the legislation in question falls within the scope of the Sewel convention.

How often has the Sewel convention been used?

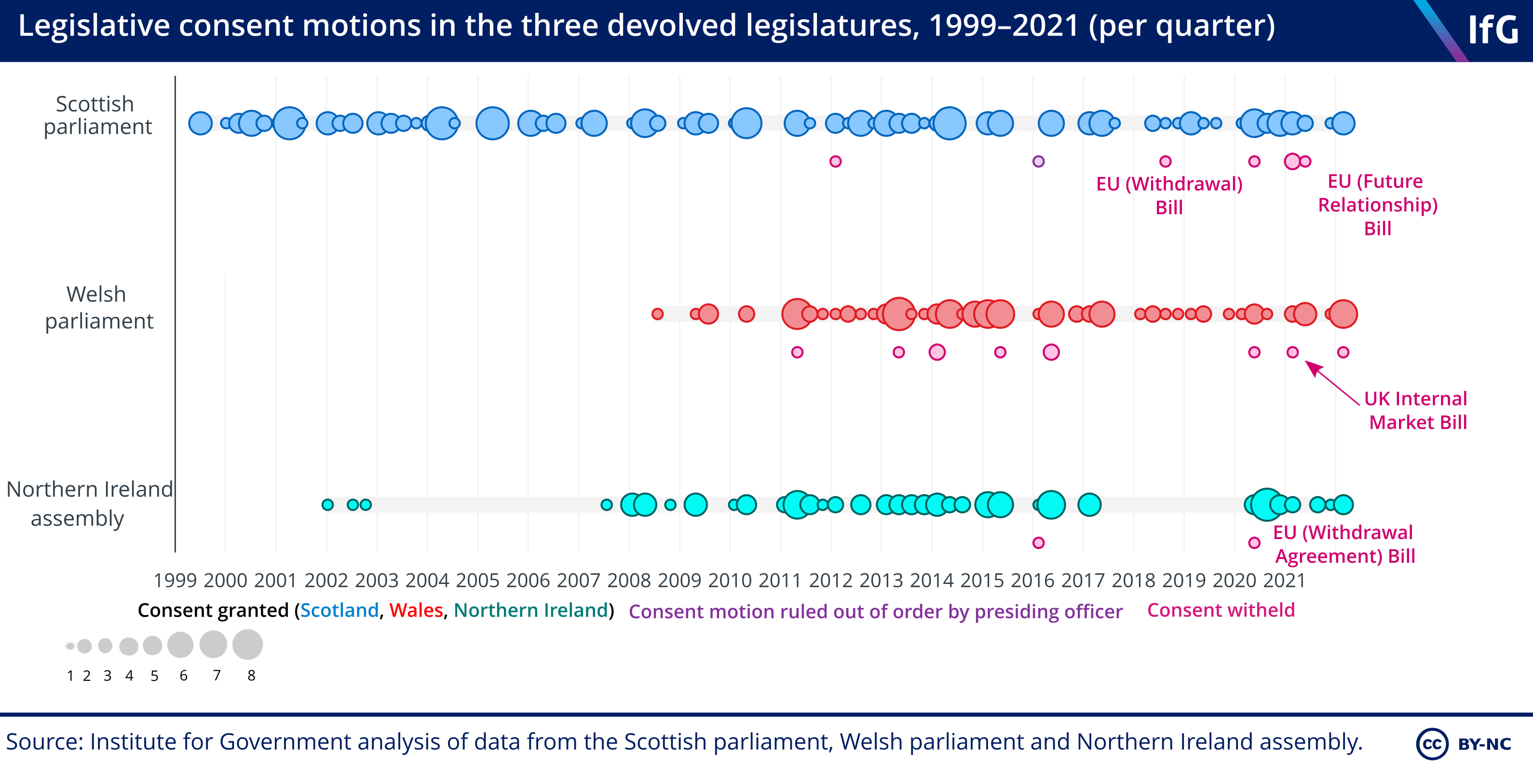

Legislative consent motions have been voted on in at least one of the devolved legislatures in relation to more than 230 Acts of Parliament since 1999. The total number of legislative consent motions stands at over 400, because many bills require consent from more than one devolved legislature, and some bills are voted on more than once.

In the vast majority of cases, the legislative consent convention has operated without controversy. In total, out of more than 400 legislative consent motions, on just 20 occasions has consent been denied, in part or in full. However, disputes have become more frequent in the aftermath of the 2016 EU referendum.

In February 2022, the Scottish parliament voted to deny consent to the Elections Bill. This is not reflected in the chart below, which shows legislative consent motions in the three devolved legislatures from 1999 to December 2021.

The absence of controversy about most consent motions since 1999 reflects the fact that the UK government normally liaises privately with the devolved governments before a bill is published, to ensure that any concerns are dealt with early on.

Many legislative consent motions also relate to technical issues that are sensibly dealt with on a UK-wide basis. For instance, devolved legislatures gave consent for the Criminal Finances Act 2017, which legislated for the recovery of criminal proceeds. All three devolved legislatures also gave their consent to the Coronavirus Act 2020, which conferred powers on ministers across the UK to tackle the pandemic.

But, on a handful of occasions, bills have been denied consent, either in part or in full.

This first happened in February 2011, when the Welsh parliament voted against giving consent to the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Bill. The Senedd has since declined to give legislative consent a further nine times. Most recently, the Senedd declined to give consent to the Professional Qualifications Bill in October 2021. In several cases, the UK parliament proceeded to pass the bill, arguing that the legislation did not relate to devolved matters.

Prior to 2016, the Scottish parliament’s only vote to deny legislative consent was on aspects of the Welfare Reform Bill in 2011. It has since voted against consent on a further seven occasions, including in relation to four Brexit-related bills.

Likewise, the Northern Ireland assembly had refused consent only once before Brexit, on the Enterprise Bill in 2015, and refused consent to one Brexit bill – the EU Withdrawal Agreement Bill, in 2020. Many bills that would have required consent from Belfast were passed without consent during the collapse of power-sharing in Stormont from 2017 to 2020.

On other occasions, for instance during the passage of the Scotland Act 2016, the threat of a denial of consent led the UK government to amend legislation, or make other concessions, in order to secure devolved agreement.

Did Brexit require devolved consent?

International relations, including relations with the EU, are reserved matters under the devolution statutes. This means that they are in the exclusive competence of the UK government.

However, much of the legislation needed to implement Brexit related to devolved matters and amends the powers of the devolved institutions. Therefore, devolved consent under the Sewel convention has been sought. But four bills relating to Brexit were passed without the consent of at least one of the devolved legislatures.

The EU Withdrawal Act 2018 was the first piece of Brexit legislation recognised by the UK government to fall within the scope of the Sewel convention.

The bill was opposed in its original form by both the Scottish and Welsh governments. Following concessions by the UK government, consent was given by the Senedd. However, the Scottish parliament voted to withhold consent. The legislation was enacted anyway, making this the first time Westminster had legislated without Scottish consent after having recognised that consent should be sought.

The UK government also accepted that the Sewel convention applied to the European Union Withdrawal Agreement Bill. In January 2020, all three devolved legislatures denied consent to the bill, but the UK parliament passed the legislation regardless.

In the new parliament formed after the 2019 election, a number of other Brexit-related bills were introduced that have fallen within the scope of the Sewel convention. Consent has been given for most of these bills. However, both the Scottish parliament (on 7 October 2020), and the Senedd (on 8 December 2020) voted to withhold consent for the UK Internal Market Bill. In addition, the Scottish parliament withheld consent for the European Union (Future Relationship) Bill on 30 December 2020.

- Topic

- Devolution Brexit

- Keywords

- Intergovernmental relations The union

- United Kingdom

- Scotland Wales Northern Ireland

- Devolved administration

- Scottish government Welsh government Northern Ireland executive

- Publisher

- Institute for Government