The government needs to implement long-term policies that tackle obesity

Arguments over ‘cakegate’ should not distract from the government binning or delaying its key policies for tackling obesity.

Arguments over ‘cakegate’ should not distract from the government binning or delaying its key policies for tackling obesity, argues Sophie Metcalfe

There was a furore when a leading public health expert recently likened office cake culture to passive smoking. But the row was a distraction from a problem which needs government action. The UK has the second highest rate of obesity in Europe and the ambitious policies announced by Boris Johnson have quietly been dropped or kicked into the long grass. Rather than arguing about cake, politicians need to find ways of developing policies that stay the course.

Key measures in Johnson’s 2020 obesity strategy have been dropped

After attributing his time in hospital with Covid to being “way overweight”, Boris Johnson launched an ambitious UK obesity strategy. It was a welcome shift in approach. Previous strategies focused on individual behaviour, promoting self-help information campaigns (like the Change4Life programme), healthy eating and exercise messaging in key settings like schools, and improving nutritional information on food labelling. But the 2020 strategy, for the first time, introduced policies designed to change the environment within which people make choices about what they eat, such as restrictions on advertising and promotions for products high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS). Health experts, who had been calling for this shift for years, particularly praised the new direction.

But two and a half years later, almost all of the strategy’s policy measures regulating the food environment have been delayed or dropped, due to feedback from industry and, in the case of the online and post-9pm TV advertising ban for HFSS products, ministers arguing that more time is needed for consultation on regulation detail and delivery. This ban is the latest casualty; it was originally billed to come into force this month but has been delayed to October 2025, leaving it up to the next government to implement. The Welsh and Scottish governments have been calling for this policy since 2015; by the time it is implemented we will have seen 10 years of inertia.

Debates about office cake distract from the real issue: successive governments have failed to reverse rising obesity trends

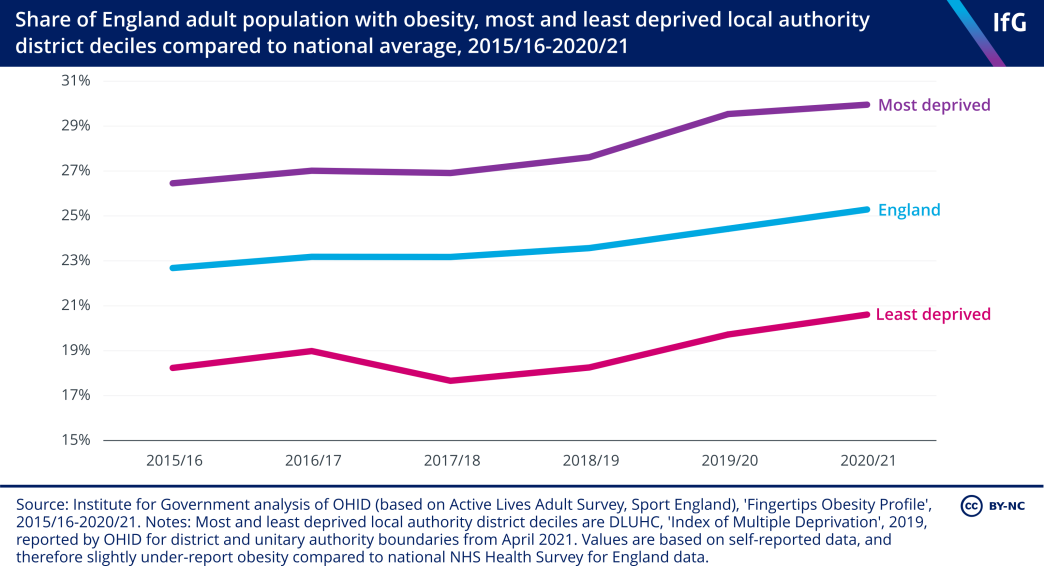

Obesity has nearly doubled in England since 1993, from 14.9% in 1993 to 28% in 2019. 16 NHS Digital, Health Survey for England, 2019. At a population level, this is a major concern; high levels of obesity within the population are associated with higher incidence of serious illnesses, such as diabetes, heart disease, liver disease and some cancers. The prevalence and effects of this are highly unequal; the average share of the adult population with obesity was 50% larger in the most deprived decile of English local authority districts compared to the least deprived decile in 2020/21, contributing to the substantial geographical health inequalities identified in the government’s levelling up white paper.

High rates of obesity adds to existing workload and budgetary pressures on the NHS and social care systems, and costs the economy more broadly through health-associated economic inactivity and lost productivity. Addressing acute crises in public services are rightly a government priority, but by failing to tackle the root causes of declining population health – like obesity – the government will only intensify future problems, and lock in associated long-term spending.

The office cake culture row is a distraction from this chronic policy problem, but it also highlights the challenge of framing government action on obesity in a productive way. Food is personal – integral to our survival, identities and communities – so it is unsurprising that people don’t like to be told what they can or can’t eat. The strong case for policy action here means that government needs to find a way forward, without reverting to solely individual-based measures which the last three decades have shown aren’t effective enough to reverse, or even stabilise, rising obesity trends.

Politicians need to find ways of developing popular policies which tackle the root causes of obesity

The good news is that there is room for the government to do more.

There is public support for nuanced industry regulation which helps rebalance market incentives and makes it easier to eat healthily. Most people like the sugar tax,

17

Pell D, Penney T, Hammond D, and others. ‘Support for, and perceived effectiveness of, the UK soft drinks industry levy among UK adults: cross-sectional analysis of the International Food Policy Study’, BMJ Open 2019, Vol. 9, No. 3, retrieved 11 November 2022, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/3/e026698

which expanded the low-sugar soft drinks market and made it easier for people to choose these over higher sugar alternatives (soft drinks sales increased by 14.9% from 2015 to 2019, while total sugar intake from liable soft drinks dropped by over a third). The HFSS product advertising ban – helping people to choose what they eat independently of the influence of advertising – is also popular.

18

Beaver, K.,’ Public supports government intervention on diet, health and advertising’ Ipsos, 2020, retrieved 25 January 2023, www.ipsos.com/en-uk/public-supports-government-intervention-diet-health-and-advertising

And polling shows that many parents particularly support regulation targeted at reducing obesity among children, who have even less control over their food choices.

19

Royal Society for Public Health, Tackling the UK’s childhood obesity epidemic, November 2015, retrieved 26 January 2023, https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/policy/obesity/childhood-obesity.html

Representatives from the food and drink industry have indicated a willingness to collaborate on useful regulation. 20 Walker R, ‘Tipping the scales: breaking the junk food cycle’, contribution to panel discussion at Bright Blue Conservative Party Conference event, 2 October 2022. Current market incentives make producing HFSS and ultra-processed foods often the cheapest and most profitable option – and companies are worried about being undercut. But as Henry Dimbleby – restauranteur and author of the National Food Strategy commissioned by Michael Gove – has shown, many within industry believe the right regulation could offer a level playing field on which industries can choose to expand healthy product options in a profitable way without losing their competitive advantage. This was the approach of the sugar tax, and with careful thought could drive wider change in the industry.

Ministers will need to listen carefully to the public and to industry. But it is also the role of government to communicate and lead action when required. The evidence on the health risks associated with high and rising UK obesity is strong enough to necessitate action. Following through on the policies announced in the 2020 obesity strategy would represent a good first step. But government needs to commit to a long-term plan to transform the food system if it is serious about reversing obesity trends and protecting the UK’s long-term public health and finances.

- Topic

- Policy making

- Keywords

- Health Social care Economy Tax

- Publisher

- Institute for Government