Devolved public services

Since their creation in 1999, the devolved governments have chosen to fund and run public services in very different ways.

Summary

The governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were created in 1999, leaving England as the only nation of the UK legislated for solely by the by the UK government. In the two decades since devolution, each of the administrations have made different choices about how much to spend on public services and how to manage them.

Scotland and Wales have generally emphasised universal access to services and collaboration within the public sector. The UK government in England has pursued more top-down techniques for securing improvement, using targets, public accountability and market-like mechanisms. Northern Ireland has mostly adopted policies from England, albeit with less emphasis on public accountability and market-like mechanisms.

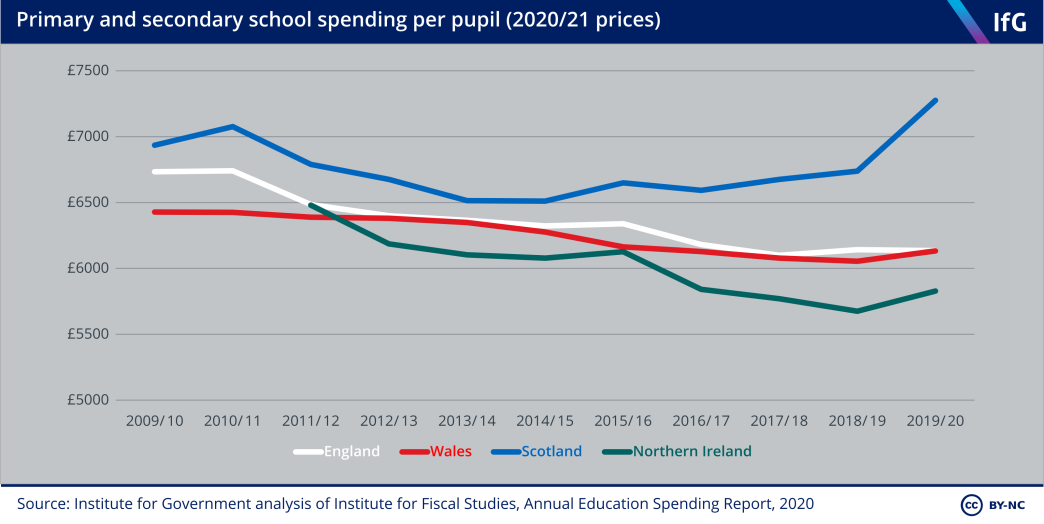

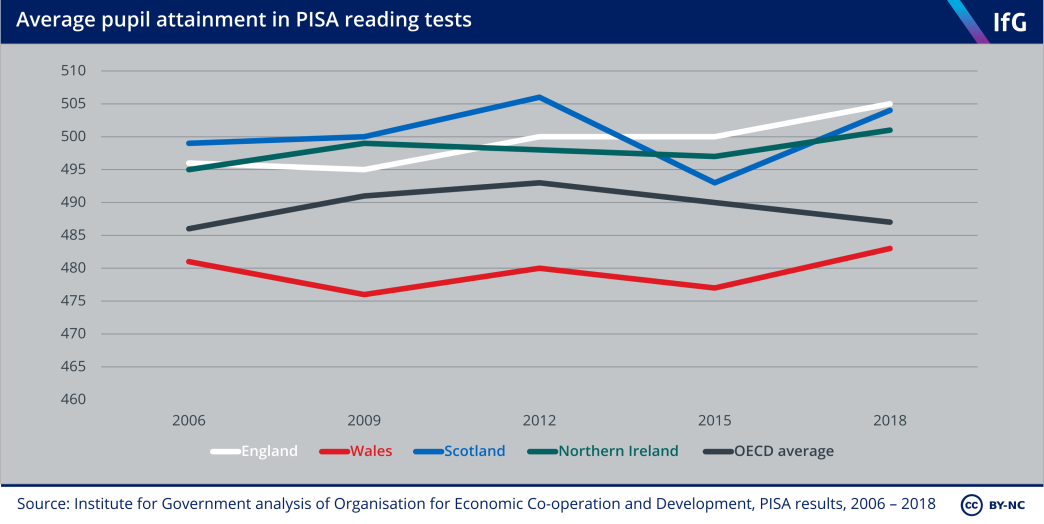

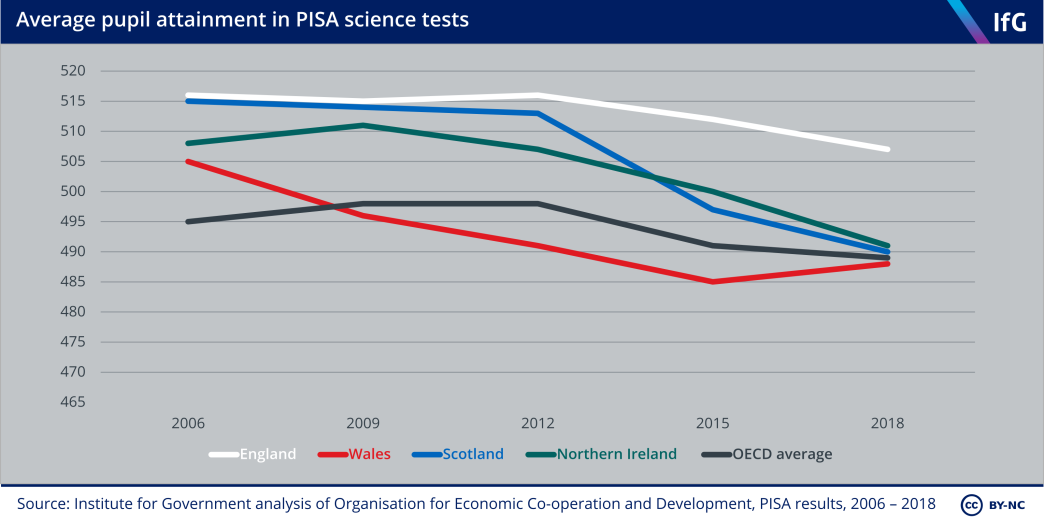

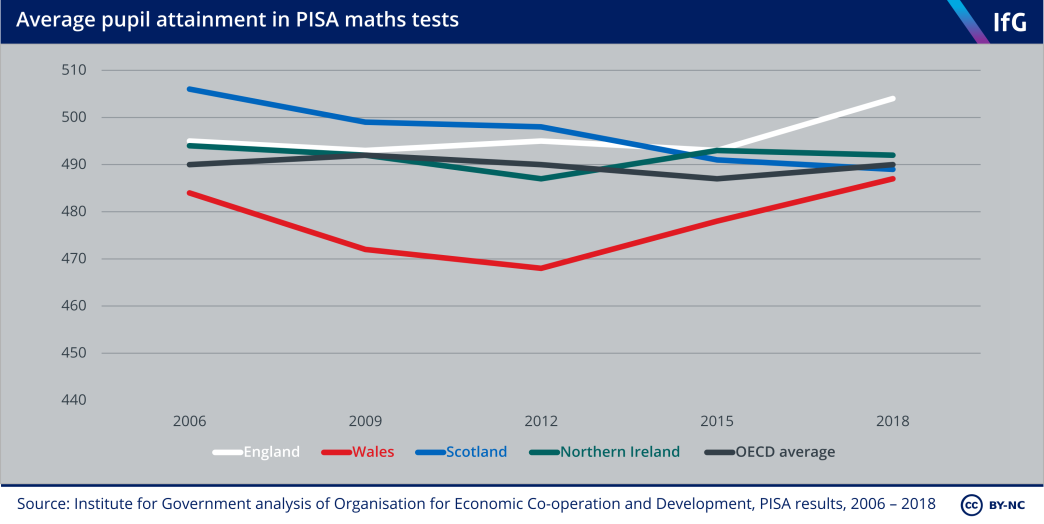

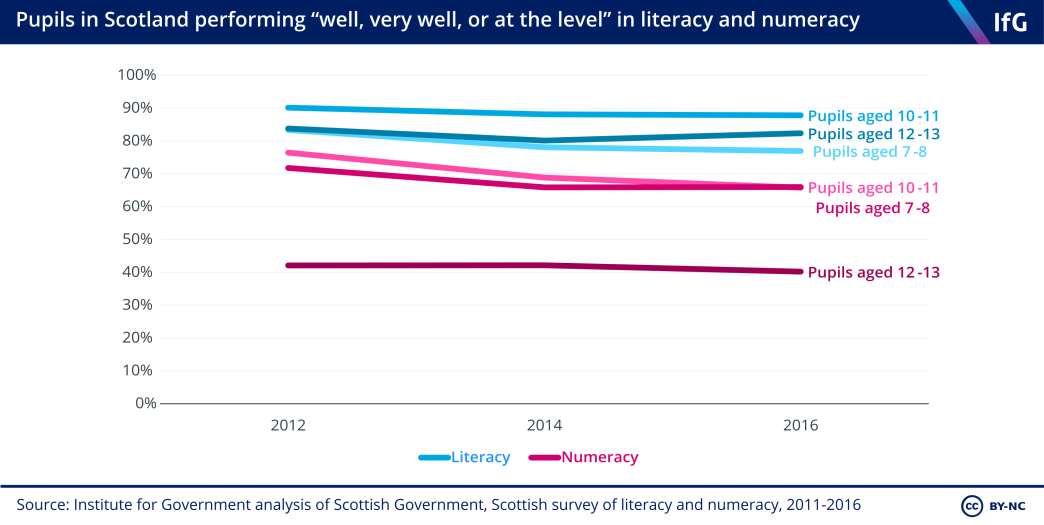

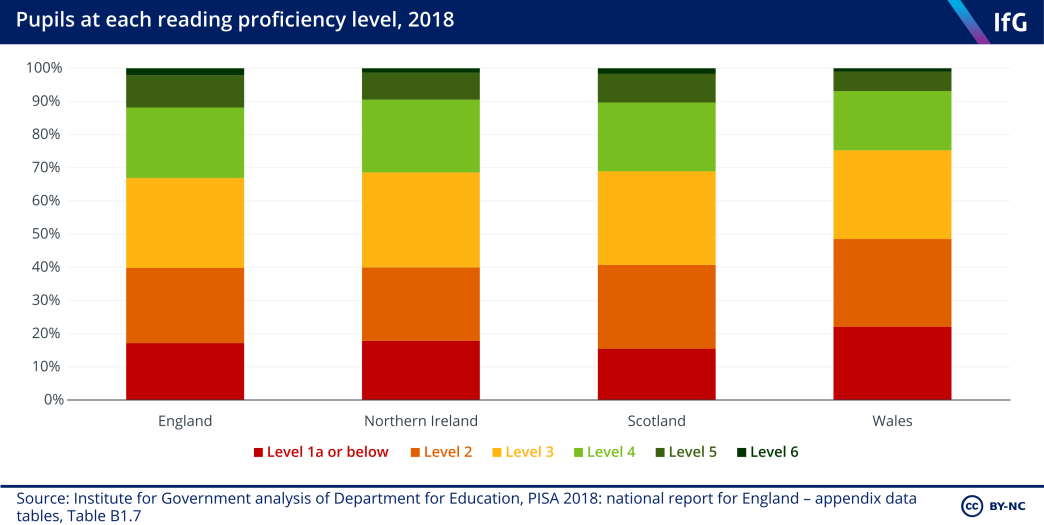

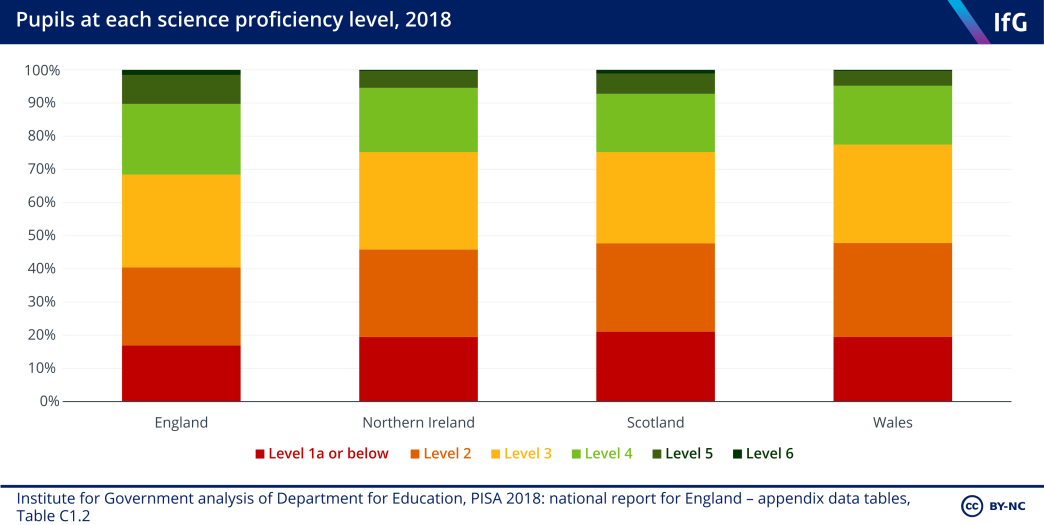

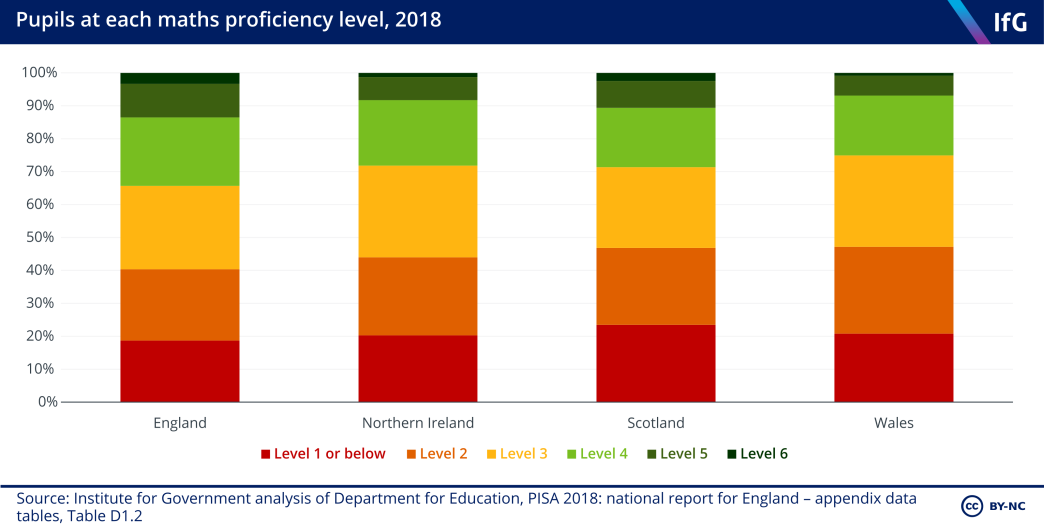

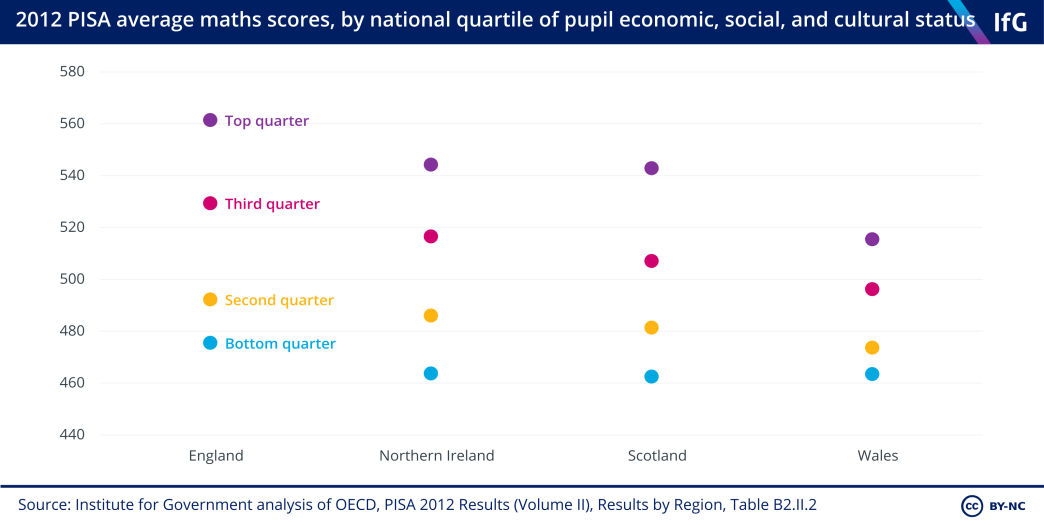

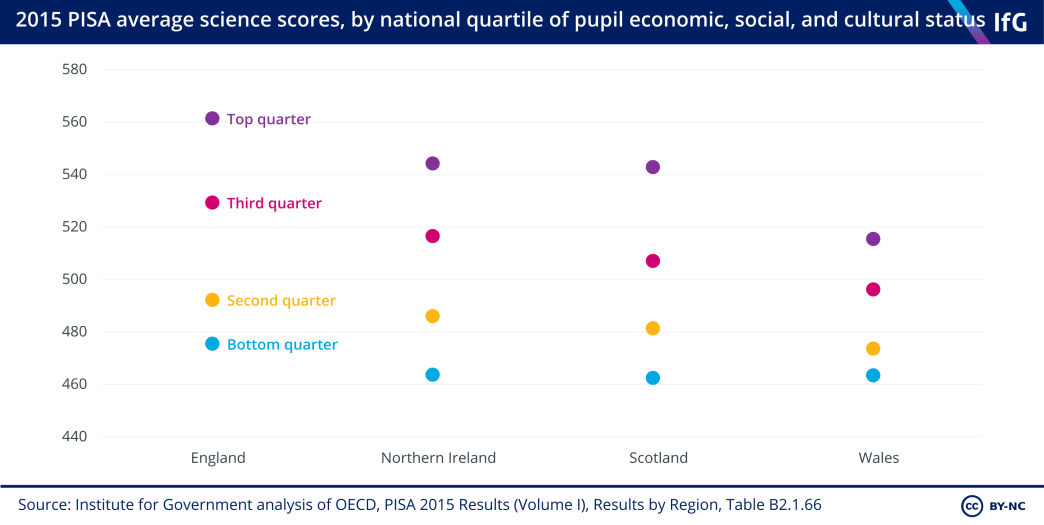

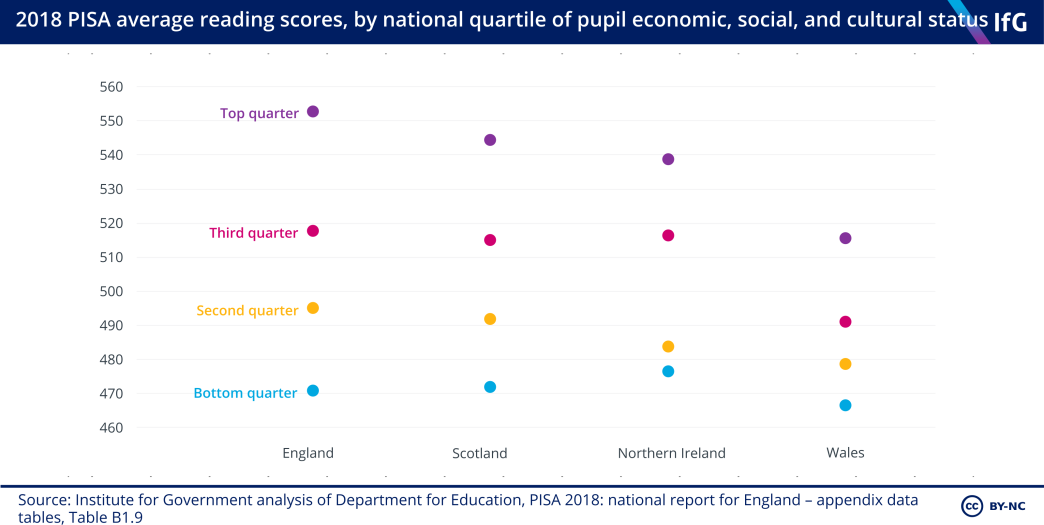

England’s public accountability and targets have had notable successes. Pupil attainment rose rapidly, and NHS waiting times fell, in the 2000s. Both improved in Scotland and Wales too, albeit initially at a slower rate. Health outcomes – notably treatable mortality – have changed at similar rates in all four nations, but those for education have diverged. Scottish pupils’ maths scores declined in international tests between 2012 and 2018, while increasing in England and Wales; Scottish science scores also fell considerably while only falling a little in England and increasing in Wales.

This report analyses how much the four nations are spending on the NHS, adult social care and schools.* It compares the four governments’ policies in these areas, evaluating how well these public services performed in the two decades from 1999 to the start of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020. It has, unfortunately, become increasingly difficult to compare performance because the four governments are collecting and publishing increasingly different data. Each chapter accordingly offers recommendations on how to improve data comparability.

* For schools, we cover compulsory schooling for children aged between 5 and 16, excluding sixth form colleges, further education, and universities. For the NHS, we cover the primary and secondary health systems, and exclude public health and the wider health system.

1. Scotland spends the most of the four nations on the NHS, social care and schools

The devolved nations all spend more per person on comparable public services than England.[1] This is partly because they have higher needs on average – such as older populations, greater geographic dispersion, higher levels of disability and lower levels of household income. But it is mainly because the UK government uses the Barnett formula to allocate devolved budgets, which preserves the higher level of spending per person that Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland had in the late 1970s, when the formula was designed.*

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland spend more per person on the NHS and social care – but only Scotland spends notably more per pupil on schools, reflecting that the devolved administrations can spend the grants they get from the UK government in line with their own priorities across devolved services.

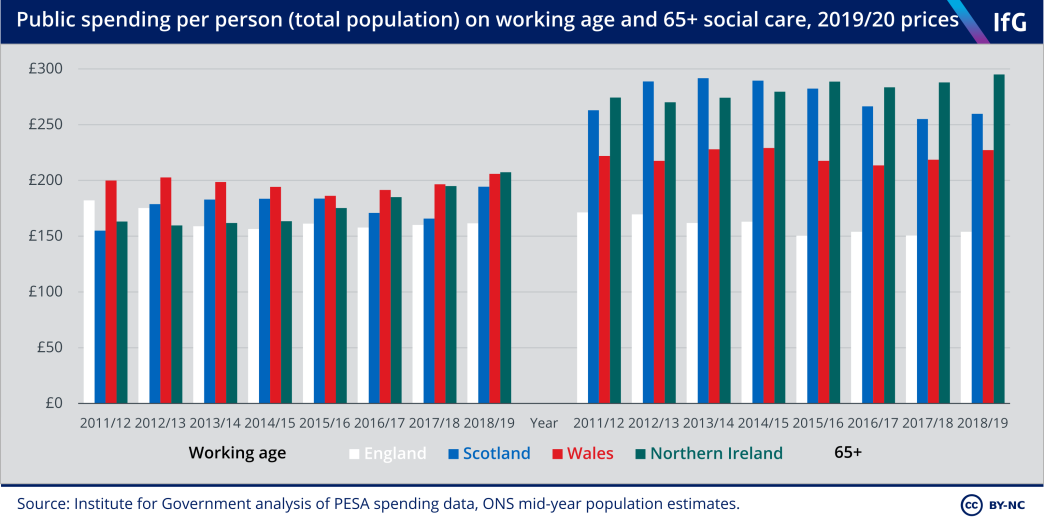

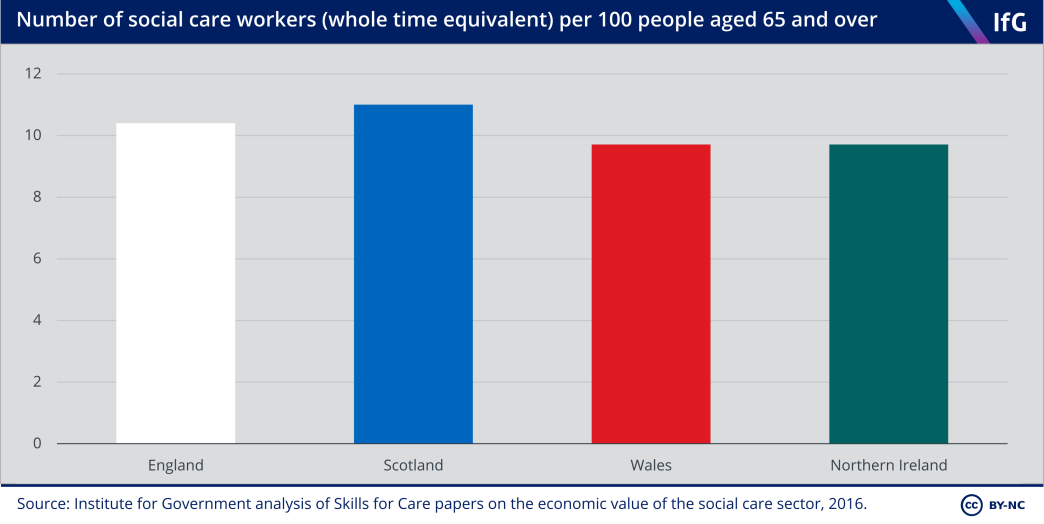

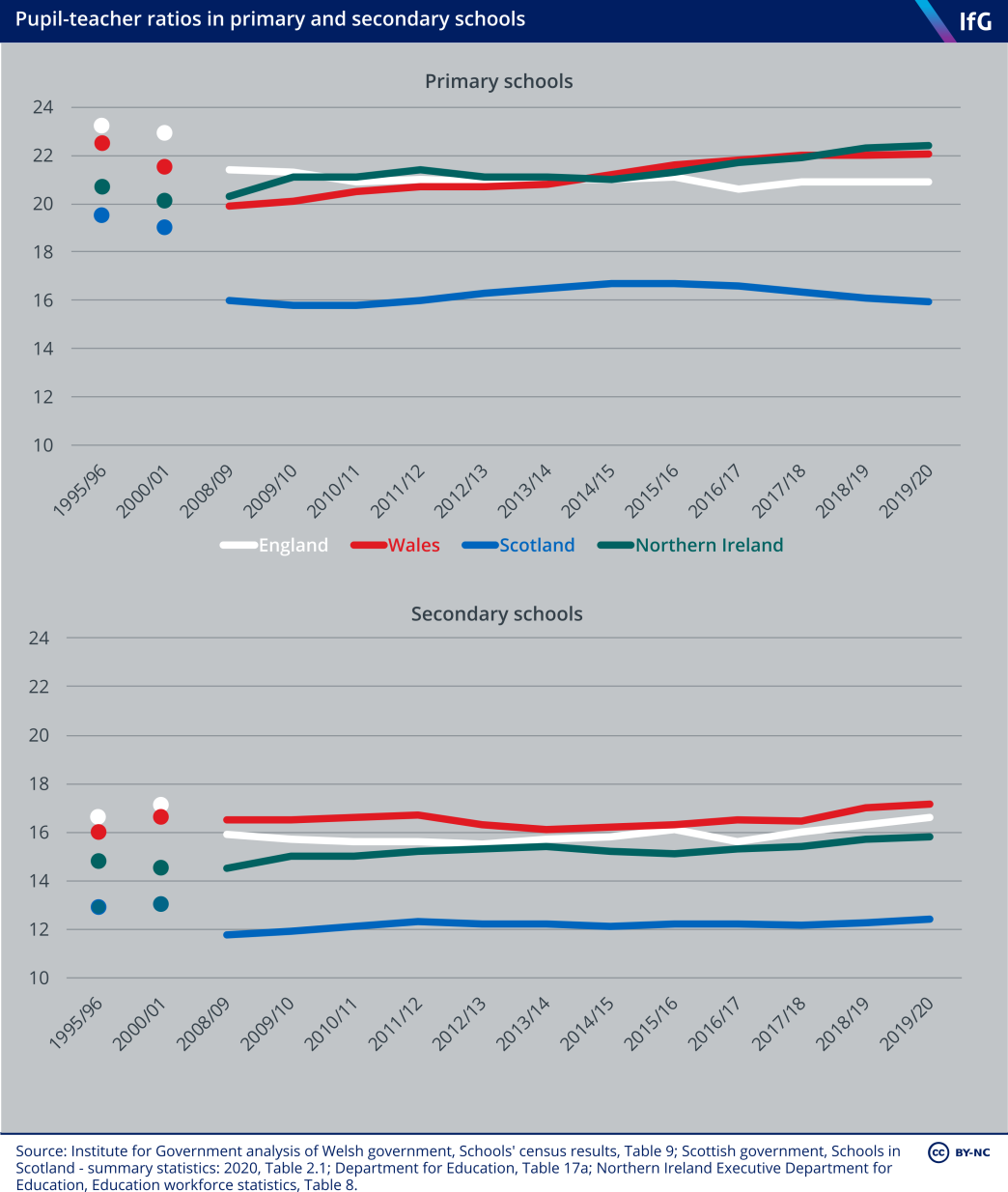

Scotland spends the most per person on health and schools, and has the most doctors, nurses, teachers and care workers per person of the four nations. This higher spending is not matched by higher need in Scotland – Wales has an older population, and a higher level of disability. Higher Scottish spending reflects that it provides some services that are not publicly funded in the other nations – such as free personal care for people aged 65 and over – and that it has more staff per pupils, patients, and social care users.

* The Barnett formula used to allocate the devolved nations’ budgets ensures that changes in devolved budgets mirror changes in UK government spending on devolved policy areas in England, thereby partly preserving the higher per person spending in the devolved nations than England which existed in the late 1970s when the formula was introduced. For more detail, see Paun A, Cheung A & Nicholson E, Funding Devolution, Institute for Government, 2021

2. The four nations made different spending choices after 1999

The Scotland, Government of Wales, and Northern Ireland Acts of 1998 allowed the three nations to decide how to allocate spending between public services within a budget largely set by the UK government.

Since then, the four nations have made different choices about which services to prioritise. England has increased health spending fastest since 1999, while the devolved nations focused on other public services.

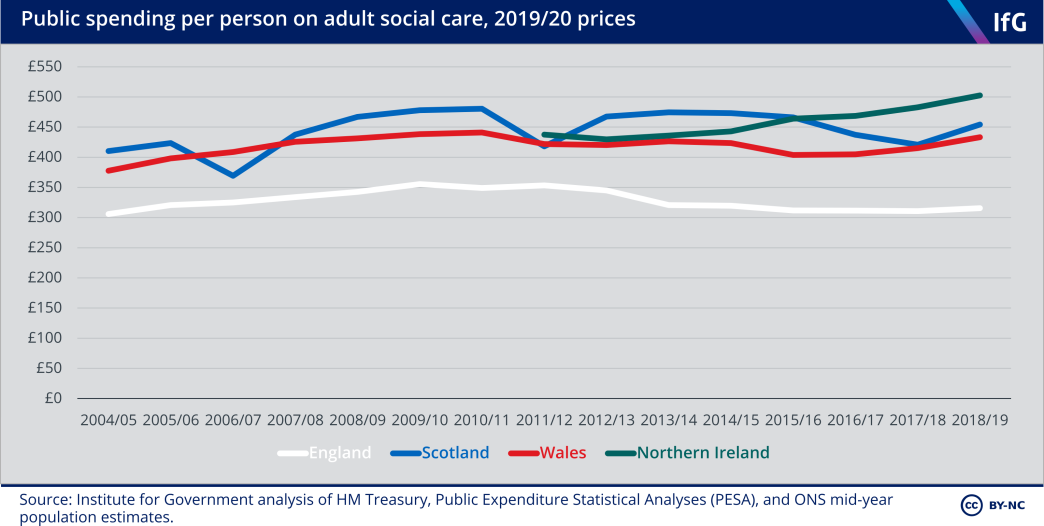

In the 2010s, when public spending growth was constrained due to austerity measures seen in each nation, England cut social care spending the most. Wales and Northern Ireland increased it: both spent more at the end of the 2010s than they did at the start, while England continues to spend less.

3. The four nations chose to run public services differently in the 2000s

Since devolution, the four nations have run public services in different ways. In the 2000s, Scotland and Wales emphasised collaboration in the public sector while England pursued a top-down model of improvement using targets and public accountability, and market-like mechanisms thereafter. The Welsh government stopped publishing school league tables and removed some primary school testing, though, along with Scotland, eventually implemented policies that more closely resembled the English government’s performance management regime. But neither deepened competition within the NHS. Scotland removed the NHS ‘internal market’ in 2004, and Wales in 2009.

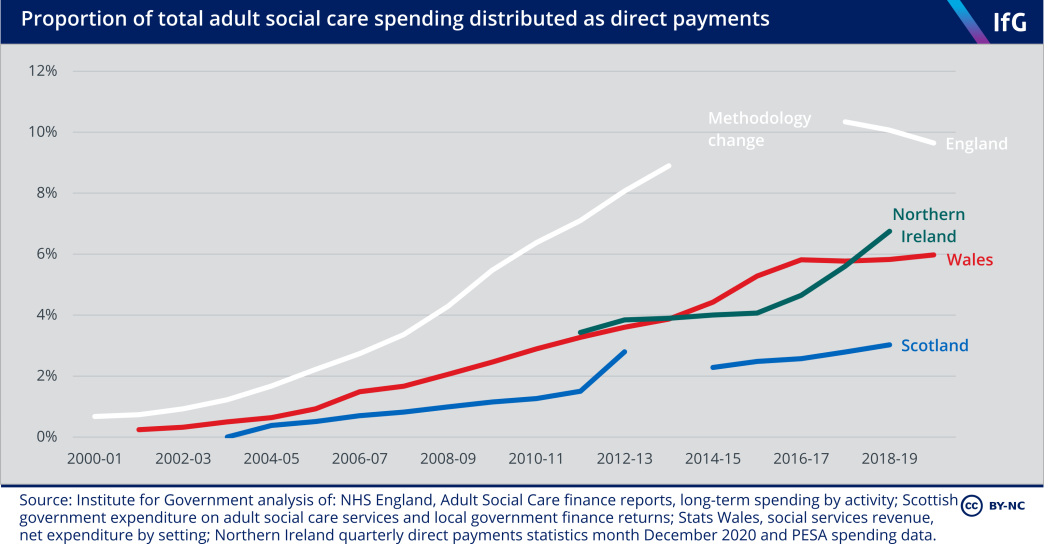

Scotland and Wales have emphasised ‘universalism’ in public services – that services are offered to all citizens, rather than that a particular targeted group. Both abolished prescription charges in 2007 and 2011, respectively. Scotland has provided free universal eye examinations since 2006, and also abolished up-front university fees in 2001, and later removed post-graduation fees in 2008. These differences are similarly evident in social care. Scotland established free personal care for those aged 65 and over in 2002, bringing it closer to the Northern Ireland offer of free in-home and nursing care. Wales did not adopt any free social care, and services are still subject to a means test.

4. The pace of divergence slowed during the 2010s

Under tight fiscal constraint, there has been less policy divergence in the 2010s, as the four nations focused on doing more with less. There has been little divergence, for instance, in social care and no major reform in any nation, although Wales repeatedly raised the means-threshold to qualify for state-funded care between 2017 and 2019, and Scotland expanded free personal care to those aged under 65 in 2019.

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 initially further championed competition in England, but since 2016 the NHS in England has in fact moved away from competition toward integration and collaboration to improve services, bringing health policy in England closer to the approach taken in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The 2021 Westminster government white paper Integration and Innovation proposes to put these changes on a statutory footing.

Scotland and England did, however, diverge on schools policy in the 2010s. The Scottish Curriculum for Excellence, introduced in 2011, focused on skills rather than knowledge, in contrast to the new English curriculum, introduced in 2014. The new Curriculum for Wales, to be introduced from 2022, similarly puts greater emphasis on skills, and draws heavily on the Scottish example.

5. Policy choices changed NHS waiting times and school attainment

Some differences in policy affected the provision, and performance, of services. The introduction of targets and public accountability in England during the 2000s contributed to a rapid fall in waiting times for elective care. Waiting times did also fall in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland – all of which did not make as much use of targets and public accountability – but notably slower than in England. The Welsh government’s decision to remove education league tables in 2002 reduced pupil attainment, particularly for pupils in the lowest-performing schools. It has since reinstated banded league tables.

In Northern Ireland, suspension of the Stormont government and political tensions have prevented implementation of reforms in health and social care, despite repeated reviews identifying areas in need of change. Throughout the 2010s patients in Northern Ireland waited far longer for elective care than in patients in the other three nations. By March 2020, almost 40% of patients on waiting lists in Northern Ireland had been waiting longer than a year just to get an appointment – in England just 0.1% of patients on waiting lists in England waiting a year or longer for the whole journey from referral to treatment.

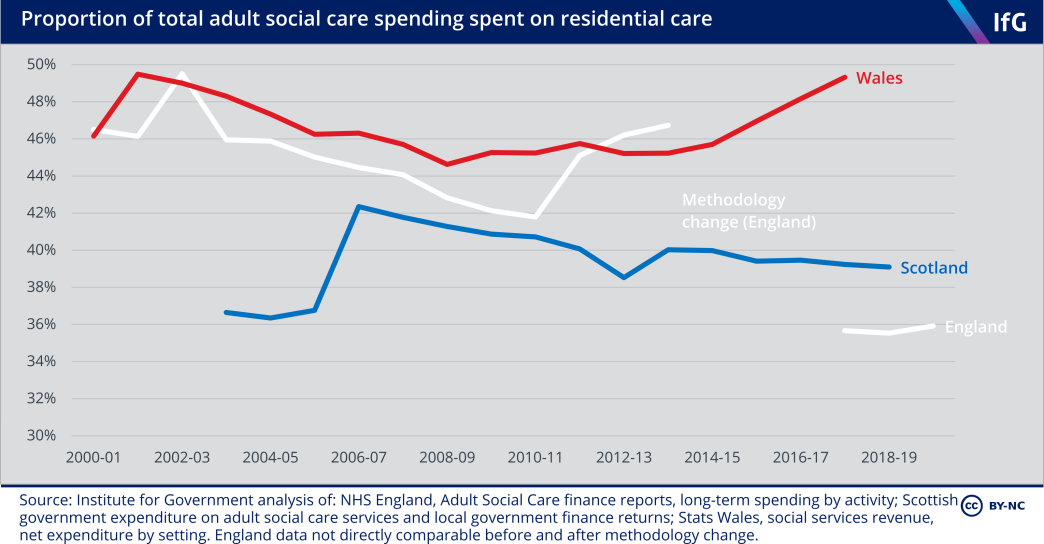

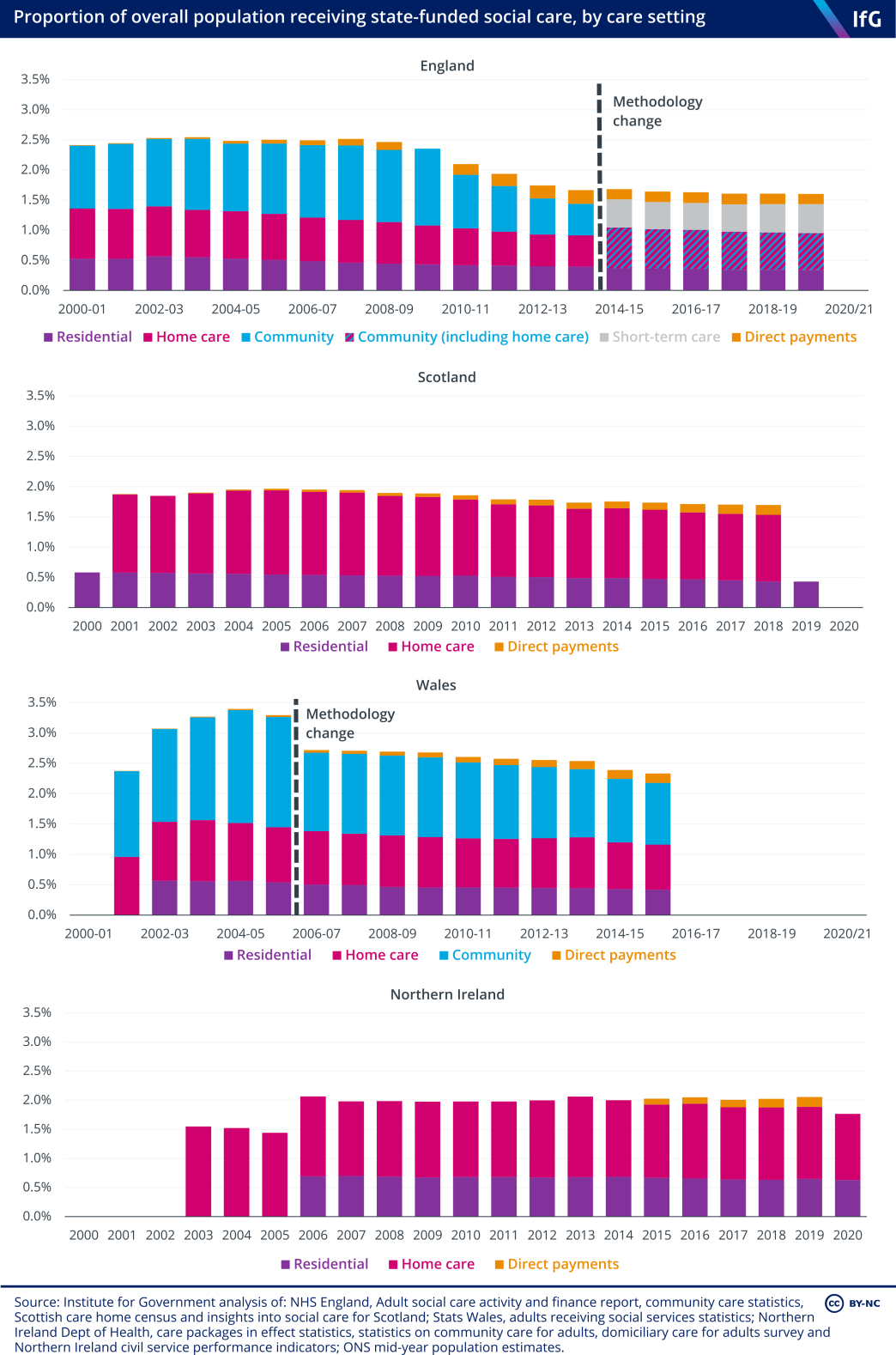

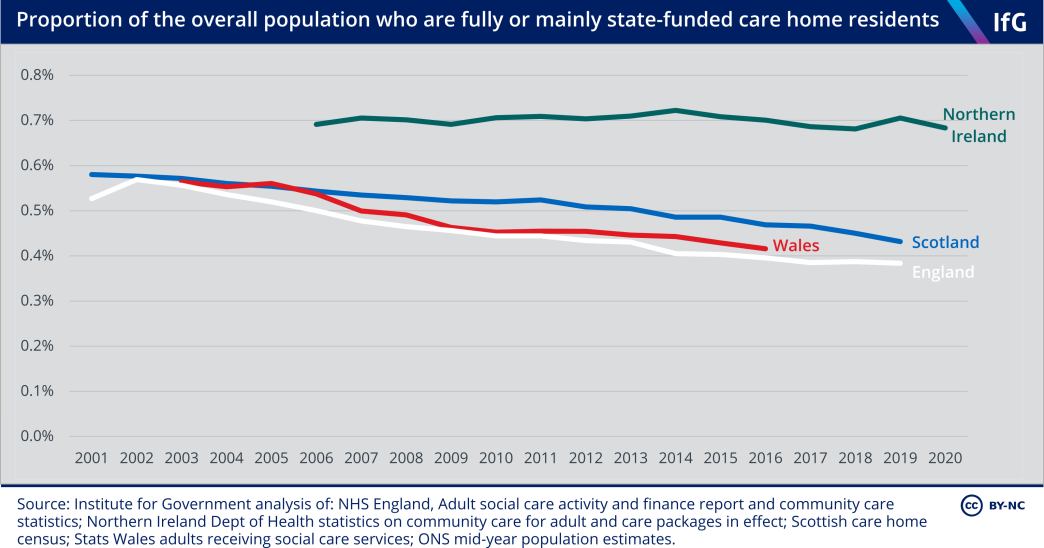

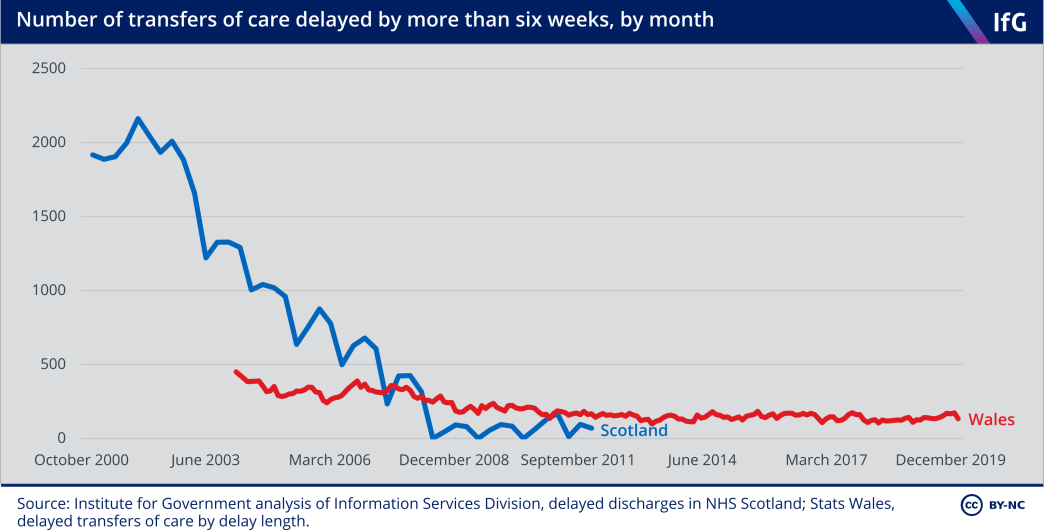

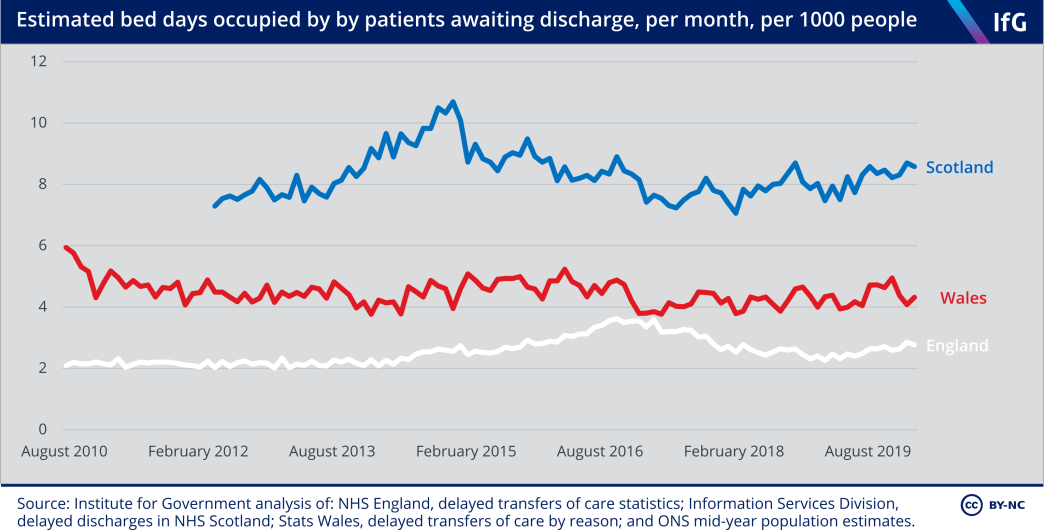

In social care, authorities in all four nations have shifted care from residential to community settings, and the number of state-funded care home residents has fallen at a similar rate in England, Scotland, and Wales. The introduction of free personal care in Scotland expanded the number of people who received state-funded care – but does not seem to have resulted in faster discharge of hospital patients there than elsewhere.

6. Devolution led to greater change in education results than in health and social care

Where comparable data are available, they show that public services perform differently in the four nations in ways that have persisted over time. Welsh pupils consistently achieve significantly lower scores in international tests than pupils in the other three nations, while the education attainment gap between the most and least disadvantaged pupils has always been largest in England. Scotland has consistently had higher rates of treatable mortality – deaths that could be prevented through timely and effective health care interventions.

But overall, health outcomes in the four nations have changed similarly since devolution. Despite changes to NHS structures, and the generosity of state-funded care, treatable mortality has fallen at similar rates in all four nations since devolution. This is partly because policy alone, no matter how varied, has a limited effect on health outcomes – these are influenced by a wide variety of other factors – and also because the policy and funding differences between the nations are small by international standards. All four have single-payer health systems that are free at the point of use and mostly state-provided.

The exception is schools, where different trends in pupil attainment have been more stark. Scottish pupils’ mean maths scores in international tests declined between 2012 and 2018, while remaining stable in Northern Ireland and increasing in England and Wales. Scottish science scores similarly fell, while falling only slightly in England and Northern Ireland and increasing in Wales.

Recommendations

The four nations should seek to learn more from each other's experiences. Their different spending and policy choices provide a fascinating experiment for policy makers to evaluate what effects policies have had, and so improve services and outcomes. Collecting and analysing data would allow policy makers to improve the performance of public services across the UK, for the benefit of the public. But in practice this kind of analysis is much harder than it should be.

It has become increasingly difficult to compare performance. This is partly because the four nations have prioritised different objectives in public services. This is legitimate – objectives are ultimately the choice of politicians and voters – but it has resulted in variations in the collection and publication of data. While goals may differ, there are ways to improve the collection and publication of data. For the four nations to learn more from each other’s experiences, we recommend:

1. The Treasury should regularly publish its analysis of the level of spending on comparable public services in each part of the UK

All four nations use public money, so should be able to account for it in the same way. As the Institute for Government argued in Funding Devolution: The Barnet formula in theory and practice,[1] the Treasury, as the UK’s central finance ministry, should ensure that spending data in the Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses are more easily comparable. It should, for example, check that academies are properly categorised as primary or secondary schools in England and ensure the division of health and social care spending in Northern Ireland matches that in England, Wales and Scotland.

It is also difficult to judge claims about investment in specific kinds of services, such as public health, from the data available in those analyses. The Treasury should review the cost of providing more granular data for the public to better judge the records of the devolved governments – and for government and service providers to better judge the effectiveness of funds allocated to different areas of services. It would be particularly beneficial to have data on:

- Health spending broken down into hospital and community health services (HCHS), and primary care

- Social care spending broken down into spending by care setting, which is currently not published in a standardised format between countries and not published at all in Northern Ireland.

2. The four governments should work to improve the comparability of public service performance data

It is also difficult to compare the performance of the four nations on key metrics, from hospital activity to exam results, because the four nations often measure or publish diff rent performance metrics (or measure similar aspects of performance in different ways).

This variation is legitimate – the devolved nations should be able to focus on measures which accord with their priorities – but all should at least clearly explain whether the data they publish is comparable with similar metrics in the other three nations. Where there are not good reasons for differences and/or where the nations have the data needed to publish statistics on a comparable basis, the nations should publish comparable data.

For this paper, we were able in most cases to check whether data we had obtained from different sources was comparable, but this was time consuming, and we received different answers from different statistical agencies, and it is possible that we have made some errors. It would be preferable, and would increase transparency about performance, if there were clear statements about data comparability.

There are initiatives underway to improve the coherence of statistics, but these have only targeted certain statistical topic areas so far. Reviews of statistics in individual countries often neglect comparability. We think that initiatives to improve the coherence of statistics should expand:

- The Government Statistical Service (GSS) and statistical producers in the four nations should work together to agree whether key education, health and social care statistics are comparable and publish this information alongside the statistics, in line with the Office for Statistics Regulation’s Code of Practice for Statistics.[2] This should build on the recent tool the GSS has published for comparing homelessness statistics in the four nations, which includes information about the comparability of homelessness data in each nation.[3]

- To hold the nations accountable for making progress, the Office for Statistics Regulation should monitor progress on comparability in its annual State of the UK’s Statistical System report.[4]

3. The four governments must work to fill key data gaps

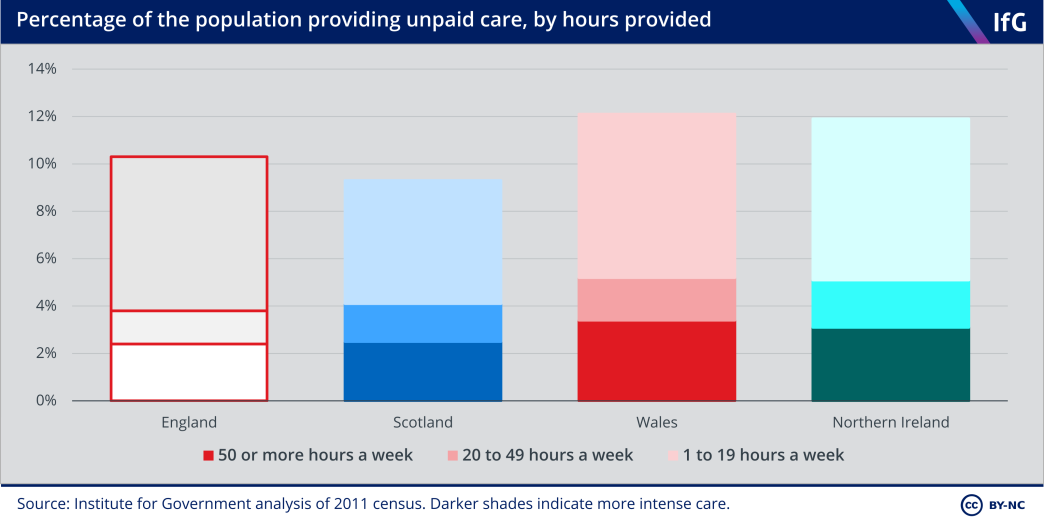

There are some important metrics for which we lack data in all nations. None of the four nations collects frequent data on unpaid care, making it difficult to assess how well the four social care systems work for those in need of care – rather than just those in receipt of it. We think that collecting survey or representative sample data on the following areas to better understand how they are performing should be a priority for all governments:

- Unpaid social care

- Private funding of social care

- Educational attainment before age 15

4. The Treasury and devolved administrations should jointly conduct or commission a new assessment of the relative spending needs of each part of the UK

As we recently noted in Funding Devolution,[5] there is wide variation in spending on public services in the four nations which is only loosely related to needs – but there is currently no way to fairly compare how generous spending in the four nations is. It is therefore difficult to tell how much of the difference in spending is attributable to differences in needs, policy or delivery.

- For health and social care, the Treasury and the devolved administrations should commission an assessment to examine each population’s underlying needs and the costs of delivering public services in the four nations, similar to the 2010 Holtham Commission. This would enable a more informed public and political debate about whether resources are fairly distributed across the UK.

The demands placed on health care and social care are influenced by the demographic and socioeconomic background of the populations in the four nations.

Health and care context

The demands placed on health care and social care are influenced by the demographic and socioeconomic background of the populations in the four nations, and the innovations in treatments and diagnostics available to treat illnesses. The four nations have very different populations, and Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have higher average needs for health care than England.[1] Overall, Wales appears to have the highest average health needs and England the lowest. All else being equal, the three devolved nations have to do more to improve health performance, such as reducing waiting times or mortality rates.

This is partly because London and south-east England are very different from the rest of England: the people there are younger, in better health, and have higher incomes. For this reason, we compare the three devolved nations to the North East of England where possible, as the population there is more demographically and socioeconomically similar to the other nations than the rest of England[2] (the region’s health needs appear to be most similar to Wales’s).[3] Comparing the North East and the devolved nations allows us to better identify the effects of differences in policy, isolated from differences in the populations.

The following analysis tracks changes in demographic and socioeconomic factors in the four nations up to March 2020, the start of the pandemic.

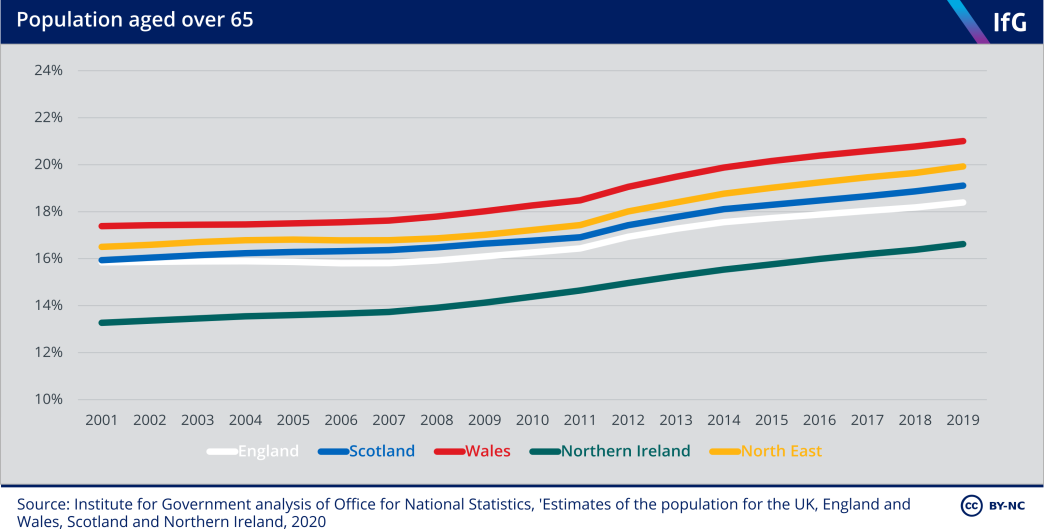

Populations are ageing in all nations, and Wales has the oldest population

Age is one important factor in a person’s health and care needs.[4] Populations are ageing in all four nations, increasing the need for health and care services.* In 2011/12 the Department of Health estimated, for example, that the NHS spends on average 2.6 times as much on someone aged 65–69 as on someone aged 30–34; the multiple is 7.2 times for someone aged 85 or older.[5]

Wales has the oldest population, and Northern Ireland the youngest – partly driven by Northern Ireland’s high birth rate during the 2000s,[6] and Wales being largely rural.[7] Scotland and England fall in the middle: a greater fraction of Scotland’s population is aged 65 and over than England’s, but England has a larger share of the very elderly – that is, people aged 85 and over. North East England has a higher proportion of people aged over 65 than Scotland or England, making it more comparable to Wales.

*Although the ageing population has not been a major driver of higher health spending over the last 20 years; this has mostly been other rising costs such as new drugs, medicines, and therapies, Licchetta M and Stelmach M, Fiscal sustainability and public spending on health, Office for Budget Responsibility, September 2016, https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/Health-FSAP.pdf

Scotland has the sparsest population

Table 2.1 Population estimates and population density (2019)

England |

Scotland |

Wales |

Northern Ireland |

North East England |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 56,286,961 | 5,463,300 | 3,152,879 | 1,893,667 | 2,669,941 |

| People per sq km | 432 | 70 | 152 | 137 | 311 |

Source: Institute for Government analysis of Office for National Statistics, ‘Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland’, 2020

Sparsely populated areas mean higher costs for providing public services.[8] All else being equal, it costs more to provide services when governments have to provide multiple facilities (such as numerous small GP practices distributed across spread out villages). England has a significantly higher population density than the other three nations, while Scotland has the lowest.

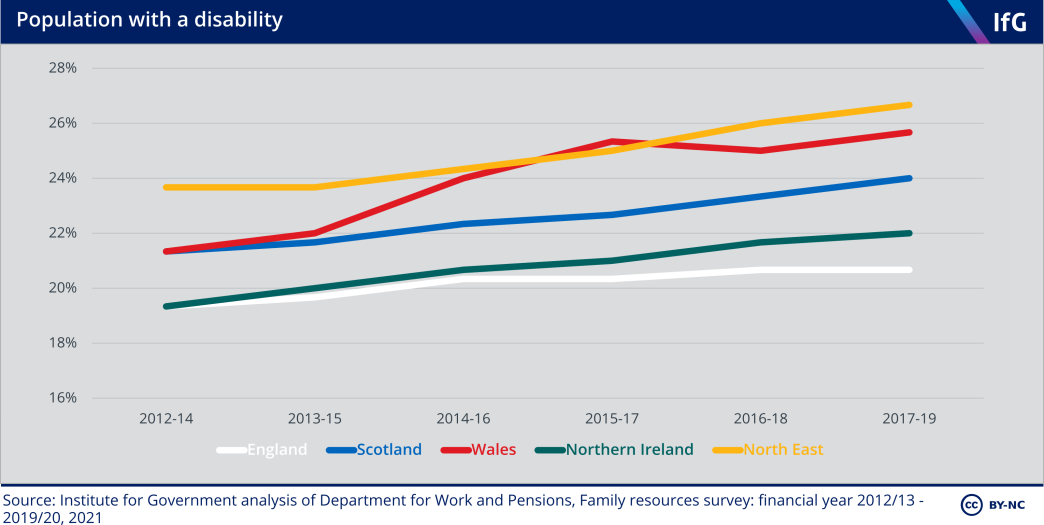

Wales has the highest proportion of people with a disability

Disability is another important factor in health and care needs: people with a disability have higher care needs on average.[9] Wales has the highest prevalence of disability among the four nations. The increase since 2012 reflects the population ageing, as older people are more likely to have a disability,[10] but also an increase in the number of working-age adults with a disability.[11]

Obesity and smoking are similar in the four nations

Age and disability are not the only determinants of need. Lifestyle factors – behaviours that affect health such as diet and smoking – also matter, though they are similar in the four nations.

Rates of obesity in the four nations were similar (ranging from 25% in Wales to 29% in Scotland) in 2019/20,[12]* and the proportion of the population who smoke has been declining since the 1990s, and is now at similar rates in the four nations.[13]

*The North East, however, has a notably higher prevalence of obesity (34%).

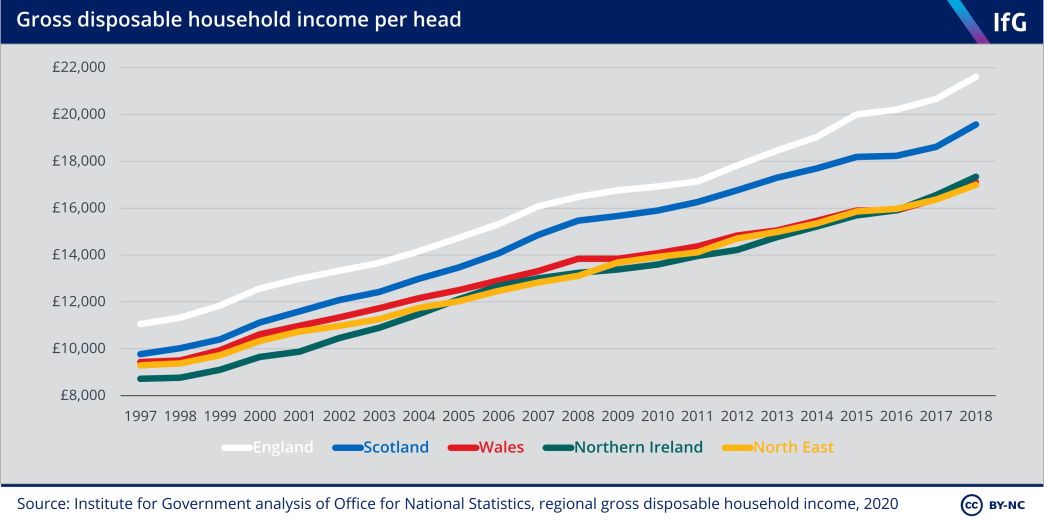

England has the highest income per person

Environmental, social and economic circumstances also influence people’s health. The conditions people live in – the adequacy of housing and day-to-day stresses they encounter – are some of the most important determinants of health.[14]

Disposable household income is one important determinant of health. High incomes allow people to buy goods and services that improve health; in addition to being less able to access these, low incomes can also reduce participation in social life, reducing feelings of self-worth and status.[15] England has the highest income per person among the four nations, mostly owing to London and the south-east. The North East has the lowest income per person of the nine English regions, and is very similar to Wales and Northern Ireland.

Private spending on health care is similar in all four nations

The amount of care people pay for differs across the four nations. People in England spend slightly more on private health care than in the other nations, but spending is low in all four nations.

Four fifths of health and care spending in the UK is paid for by the state (78% in 2018) with the remaining fifth made up of care purchased by individuals (17%) and the amount that employers and individuals spend on health insurance (3%).[16] Health insurance coverage is slightly higher in England than in the devolved nations[17] but most insurance is not comprehensive[18] (with many long-term and resource-intensive treatments not covered).

On average, English households spend £16–68 more per year on ‘hospital services’ (including dental care and private care), and £63–78 more per year on insurance premiums[19] than households in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Households in England also spend £15–36 more per year on medicines and prescriptions – although a large part of this will be because Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland removed prescription charges in 2007, 2010, and 2011 respectively.[20]

Overall, we consider the differences between the nations are small enough not to seriously alter the demands the NHS faces in each nation.

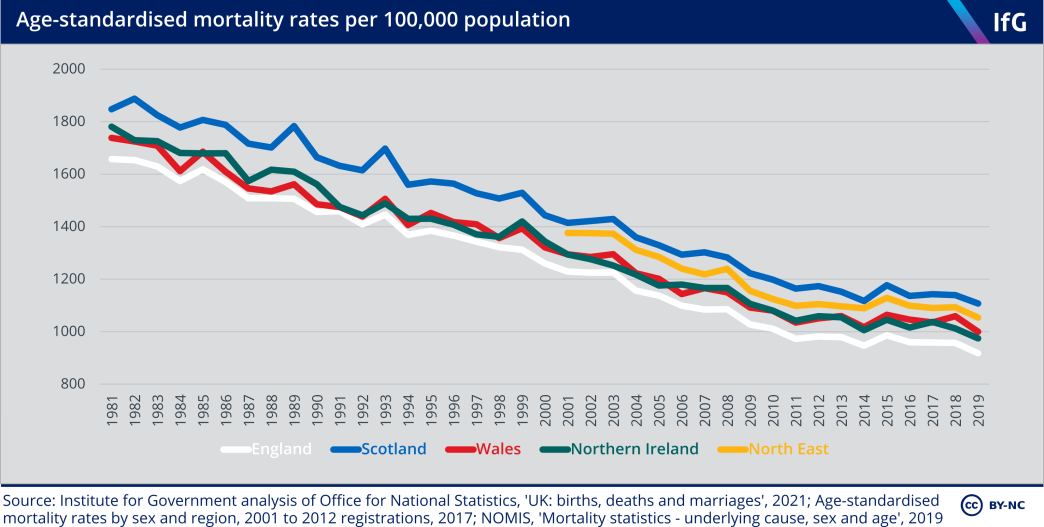

Scotland has the highest mortality rate

Annual age-standardised mortality rates show the number of people dying each year, adjusted for different population age structures to allow fair comparison over time and between places. A higher mortality rate is one indication of higher underlying needs.[21]

Scotland has consistently had higher mortality since at least the 1950s,[22] but the trends in the four nations were very similar before and after devolution. Owing to improvements in treatments for heart disease and stroke and reductions in smoking, among other factors, mortality steadily declined from 1981 to 2011, but has since declined much more slowly – a pattern also evident in similar European countries.[23] The slowdown is caused by a range of factors including steep spending cuts in the years following the 2008 financial crisis, multiple bad winter flu outbreaks in the 2010s, and increases in Alzheimer’s and dementia.[24]

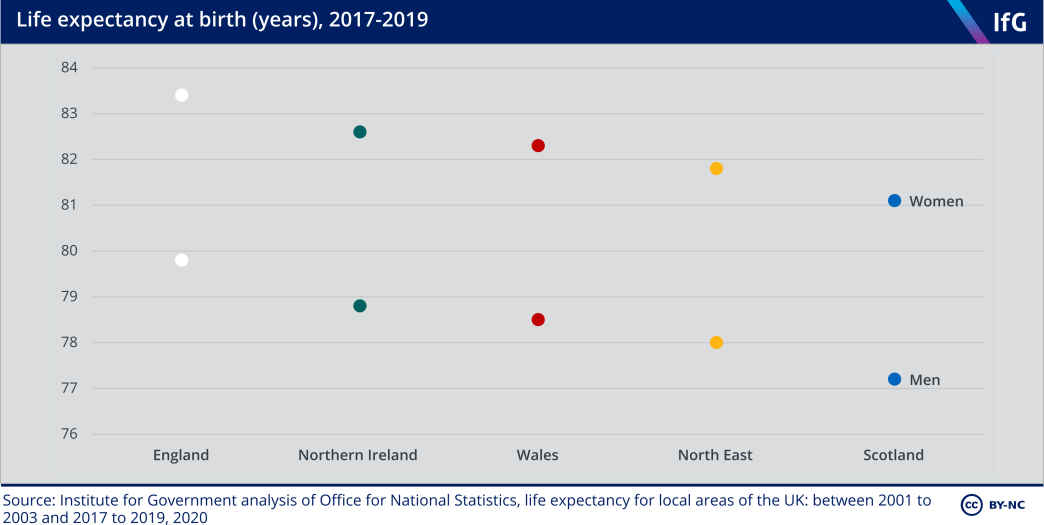

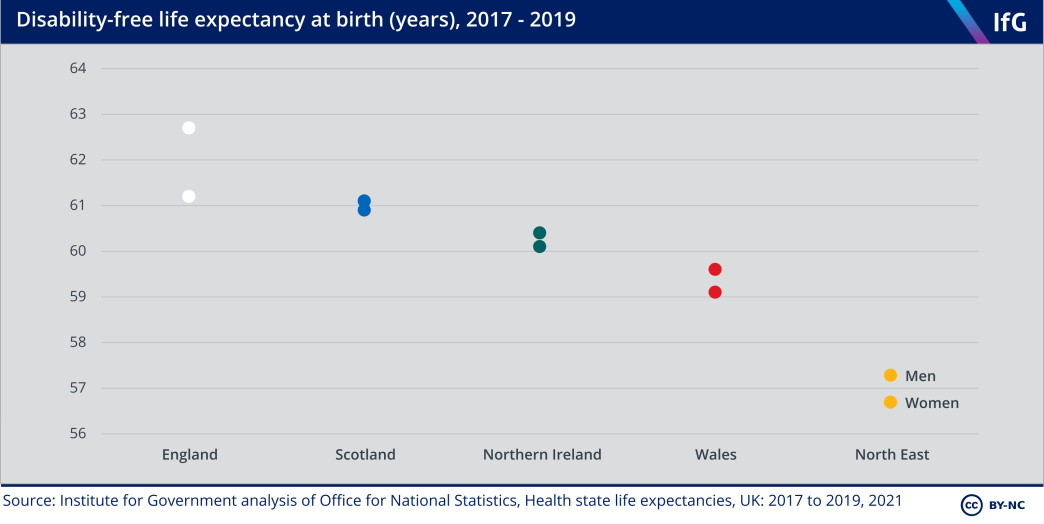

The differences in life expectancy at birth in the four nations mirrors the differences in age-standardised mortality rates. In 2017–19, England had the highest life expectancy at birth, and Scotland the lowest.

Disability-free life expectancy – how long people can expect to live without a limiting long-term illness – shows a slightly different pattern. A lower disability-free life expectancy is likely to be associated with higher needs, as people develop disabilities requiring health and/or care services at earlier ages. England, again, performs best on this metric, and people in England can expect to live the longest without a disability.

The three devolved administrations spend more per person on health than England.

NHS

The three devolved administrations spend more per person on health than England. This is because the way that the UK government allocates their budgets – using the Barnett formula – preserves the higher level of overall spending per person set when the formula was established in the late 1970s.[1] Scotland spends more on health than it would if all UK health spending were allocated according to need. The opposite is true in Wales.

In the 20 years since devolution, the four nations have made different policy choices about how to run their health services. England made extensive use of targets and public accountability in the early 2000s as part of the Blair government’s public service reforms, and increasingly emphasised market-like mechanisms thereafter. The three devolved nations put less emphasis on targets and public accountability, and Scotland and Wales removed the NHS purchaser-provider split* in the 2000s. In the 2000s waiting times for elective care and ambulance response times improved faster in England than in the other three nations, though Scotland and Wales later made greater use of targets.

Despite the intentions of the 2012 health reforms in England that aimed to enhance competition in the English NHS, there was greater policy convergence in the 2010s, with all nations encouraging collaboration and integration between the NHS, social care and local government.

But in the same decade waiting times for A&E and elective care grew longer across the UK as the four governments restrained increases in health spending. It is difficult to compare performance now owing to a lack of truly comparable data, but it is clear that England and Scotland have notably better performance on waiting times than Wales and Northern Ireland.

Overall health outcomes in the four nations have changed in similar ways. Treatable mortality – deaths that can be avoided through timely and effective health care interventions – and life expectancy in the four nations have changed in similar ways since devolution.

* The purchaser/provider split refers to the practice whereby a commissioning organisation purchases services from the NHS or independent providers of health care. It was introduced in the UK in 1991.

The NHS in the four nations

This chapter assesses the NHS in each nation, from devolution to the start of the pandemic. It does not cover public health services or wider health services.*

The NHS was the largest area of public spending devolved to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in 1999. Day-to-day health care spending represents around a quarter of total current spending in each nation, although England spends slightly more of its budget on health (26%) compared to Scotland (23%), Wales (23%) and Northern Ireland (22%).[2]

Each government has chosen to run its health care system differently since devolution, but by international standards the four health systems are very similar – publicly funded, centrally managed, and free at the point of use. There was greater policy convergence in the 2010s, as all four nations have sought to find ways to encourage collaboration and integration between health and social care services.

Table 3.1 Policy differences as of 2020

|

|

Purchaser/provider split |

Commissioning organisation(s) |

Payment by activity |

Foundation trusts* |

Administrative integration between health and social care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | Yes | NHS England and clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) | Yes | Yes | Integrated care systems (proposed)[3] |

| Scotland | No | N/A | No | No | Integration authorities |

| Wales | No | N/A | No | No | Regional partnership boards (under consultation)[4] |

| Northern Ireland | Yes |

Health and Social Care Board (being phased out)[5] |

No | No | Fully integrated health and social care |

* We define public health as services designed to prevent disease, promote health and extend life among the population as a whole, such as local authority smoking cessation services. We define wider health services as services that affect people’s health and wellbeing, such as housing policy.

** Foundation trusts are health care trusts with greater financial and managerial autonomy, including being accountable to a board of governors rather than the health secretary, greater freedoms about how to spend money and greater flexibility in staff pay and management.

England

England managed the NHS differently after the Blair government’s decision to increase UK health care spending to the European average in the 2000s.[6] The white paper published in 2000[7] tied higher funding to NHS reform,[8] including targets for elective surgery waiting times[9] and for all patients to be seen within four hours of arriving at A&E. This became known as the ‘targets and terror’,[10] and later ‘naming and shaming’,[11] approach to managing the NHS.

The white paper argued that poorly performing hospitals were too often given extra funding, while hospitals that performed well were given less funding, and concluded that “the current system penalises success and rewards failure”.[12] Aiming to ensure that higher funding resulted in better performance, the government put targets in place, and after 2001 scored NHS organisations between zero and three stars each year. Poor performance resulted in sanctions, reputational damage and occasionally sacking chief executives.[13],[14] Good performance resulted in rewards – high-performing hospitals could become foundation trusts, with greater autonomy from direct government control – a policy not introduced in the devolved nations.[15] The combination of higher funding and public targets had some success in reducing waiting times (see ‘NHS performance’ section below).

The New Labour government put more emphasis on user choice and provider competition to improve services after 2005, when star ratings were removed.[16] England developed the health care quasi-market established in the 1990s by introducing a tariff payment system known as ‘payment by results’, making greater use of the private sector (encouraging privately run independent sector treatment centres to compete with publicly run NHS trusts to provide elective surgeries),[17] and allowing patients to choose where they received secondary care,[18] which came into full operation in 2006.[19]

The coalition government continued in this direction while Andrew Lansley was secretary of state for health. The Health and Social Care Act 2012[20] strengthened and made explicit the role of competition within the NHS, by creating an independent commissioning board (which later became NHS England) and GP-led clinical commissioning groups (CCGs).[21] The 2012 Act was complex and controversial, and there is a widespread perception that it did not create an effective market in the NHS.[22]

In contrast Lansley’s successor, Jeremy Hunt, prioritised safety and quality during his time as health secretary (2012–18),[23] by strengthening the role of the Care Quality Commission (CQC) in inspections and regulation.[24] The CQC’s influence in England is much greater than its counterparts in the devolved nations, which have less authoritative inspectors and regulators.[25]

Under both Hunt and his successor and current postholder, Matt Hancock, England has put increasingly less emphasis on user choice and provider competition to improve services.[26] NHS England’s Long Term Plan, published in 2019, emphasised integration and ‘integrated care systems’, which would encourage NHS providers, commissioners and local authorities to collaborate.[27] A 2021 government white paper titled Integration and Innovation[28] in effect proposes to reverse some of the changes made in the 2012 Act.[29]

Scotland

In contrast to England, Scotland placed greater emphasis on partnerships between health and social care providers, and less on competition and the private sector, in the 2000s.[30] It removed the internal market in 2004 by abolishing NHS trusts and the purchaser/provider split. The Scottish government combined acute and primary services in 15 health boards in 2000[31] and created ‘community health partnerships’ in 2004. The latter were designed to improve integration between health and social care – an early example of integration that became a key goal in the 2010s.[32]

Higher health spending in Scotland was not explicitly linked to reform, and in the early 2000s Scotland did not use a stringent performance management system. It did, however, move closer in 2006 through ‘Health Improvement, Efficiency, Access and Treatment’ (HEAT) targets – which set specific targets for health boards – and local delivery plans, designed for the government to hold health boards accountable. The targets did not have explicit sanctions or rewards, but performance was publicly reported, as in England.[33]

Scotland’s strategy to improve quality of care and patient outcomes differs to that of the other three nations.[34] It has a long-standing relationship with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston in the US, which helped design and run the Scottish Patient Safety Programme from 2008. In contrast to the primarily centralised change programmes in England, Scotland uses “a model of small-scale testing and revision of new quality improvement initiatives, and a relatively informal approval and expansion of initiatives”.[35]

Scottish health policy since devolution has been remarkably stable, despite the change in political control at Holyrood in 2007, in contrast to near-constant change in English health policy.[36] Scottish policies emphasised collaboration in both the 2000s and 2010s,[37] although health and social care have been administratively integrated only since 2016.*

* In 2016 Scotland replaced community health partnerships with 31 integration authorities, which had a wider range of powers. See Dayan M and Edwards N, Learning from Scotland’s NHS, Nuffield Trust, July 2017, retrieved 22 February 2021, retrieved 22 February 2021, pp. 22–24, www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-07/learning-from-scotland-s-nhs-final.pdf; Timmins N, The four UK health systems: Learning from each other, The King’s Fund, 2013, retrieved 22 February 2021, p. 11, www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_ summary/four-uk-health-systems-jun13.pdf

Wales

Like Scotland, Wales neither used stringent performance management, nor sought to increase competition in the early 2000s.[38] It instead aimed to improve services through “more co-ordination between providers”,[39] and Wales’ first unique devolved health policy document in 2001 aimed to improve broader public health services.[40] A focus on public health and preventative measures have been a distinctive feature of Welsh health policy since devolution.

In the early 2000s, the Wanless review (2003) and the Auditor General for Wales (2005 and 2006) reported that Welsh hospitals were facing severe pressure, partly as a result of inadequate performance management, arguing that the current system “rewarded failure” by allocating more money to poorly performing hospitals.[41] In response, the Welsh government revised its performance management system, and introduced higher profile ‘Tier 1’, or ‘key priority’, targets that were “subject to very close attention by health boards, trusts and Welsh Government”[42] in 2011 – an approach with similarities to that taken in England and Scotland,[43] albeit with less stringent performance management.[44]

Like Scotland and England after 2014, Wales tried to improve collaboration and integration in the 2010s. The Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014 “introduced a legal duty on local authorities to promote integration of health and social care when carrying out their social services functions”,[45] and created regional partnership boards to bring together health boards, local authorities and others to improve integration.[46]

Northern Ireland

Health policy in Northern Ireland since devolution has primarily been marked by lack of change – partly because of the suspension of the Northern Ireland executive between 2002 and 2007, and then again between 2017 and 2020. Combined with the difficulty of agreeing reforms in coalition administrations (mandated by the Belfast/ Good Friday Agreement) even when in operation, Northern Ireland has implemented fewer policy changes than the other three nations.

Northern Ireland is also distinct in having had administratively integrated health and social care boards since 1973. Northern Ireland’s four health and social services boards took responsibility for providing social care from local government in 1970 – long before England, Scotland and Wales considered integration a priority.[47] The primary reason for this was because of concerns about “systematic discrimination by local governments”, which escalated sectarian tensions.[48] Integration has had some benefits such as (seemingly)* patients in hospitals waiting less time to be discharged than in the other nations,[49] but Northern Ireland faces some of the same problems as Scotland, Wales and England. The higher political profile of health care – its local visibility and larger budget – tends to mean that it dominates over social care within health and social care boards.[50]

While reforms have been comparatively infrequent, the Northern Ireland executive did introduce changes to its health system in 2009, since when there has been a single commissioning Health and Social Care Board and five health and social care trusts that provide care.[51] Northern Ireland maintained a purchaser/provider split until 2016, unlike Scotland and Wales, but in practice its small population and limited private sector meant that there was little real competition to provide services.[52] As a result Northern Ireland has tended to emphasise co-operation rather than competition, similar to Scotland and Wales.[53]

The problems in Northern Ireland’s health system are well known, with politics the main obstacle to change. There were seven major reviews of health and social care between 2001 and 2016, which all made similar recommendations: reduce reliance on acute hospitals, centralise some specialist services and emphasise healthy behaviour to reduce the prevalence of preventable illnesses.[54] The most recent review (Bengoa, 2016) identified “review fatigue” as a problem in itself and concluded that successive governments had spent a lot of time and resources analysing challenges, identifying weaknesses and making recommendations, but had failed to enact reforms to change the system.[55] The suspension of devolved government between 2017 and 2020 and the coronavirus pandemic have severely hampered progress in implementing Bengoa’s reforms.[56]

* Delayed discharges are counted differently in Northern Ireland, so it is not possible to compare performance in a like- for-like way. See Ham C, Heenan D, Longley M and Steel D, Integrated care in Northern Ireland, Scotlandand Wales: Lessons for England, The King’s Fund, 2013, retrieved 10 March 2021, pp. 16, www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/integrated-care-in-northern-ireland-scotland-and-wales-kingsfund-jul13.pdf

NHS spending

The devolved administrations spend more per person than England

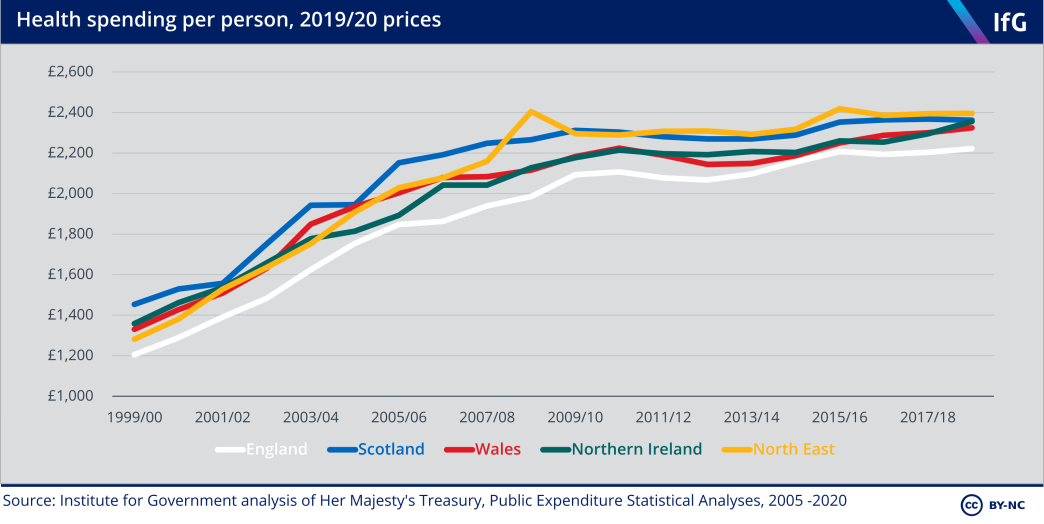

Health spending – spending on medical equipment, outpatient services, hospitals, public health, and research and development[57] – grew very differently across the first two decades of devolution. In the first decade (1999 to 2009), there was rapid growth in spending, but in the second decade (2010 to 2019) spending rose much more slowly.

Health spending has evolved similarly in all four nations, although Wales cut spending the most at the start of the 2010s, reducing spending per person by 3.4% in real terms between 2010/11 and 2013/14 to protect spending on local government and social care. The intention was to focus on wider public health and prevention[58] – but perceived poor performance and media pressure led the Welsh government to reverse course from 2014/15.

Of the four nations, Scotland spends the most per person and England the least. England’s lower spending is partly explained by its comparatively healthier and younger population – the populations of the devolved nations have higher health needs than the population of England overall – and partly because all three devolved nations have a higher overall level of public spending.[59]

Comparing spending in North East England – which has higher health needs than the rest of England – to the three devolved nations illustrates this. The North East spends more per person than the English average because England’s internal formula allocates health care spending according to need (accounting for age, sex, disability, deprivation, supply costs and health inequalities).[60] Due to England’s internal formula and the choices made by the devolved governments, spending grew faster in the North East than in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland between 1999/00 and 2011/12.

After adjusting for health needs, Scotland spends more than Wales and England

Age is one of the biggest determinants of health spending.[61] To account for how much of the difference in spending between the four nations is because of the different age structures of their populations, Table 3.2 compares each nation’s actual spending to what would be expected if they spent the same per person of a given age as England does.

Table 3.2 Expected age-adjusted health spending per person in the devolved nations, 2018/19

|

|

Scotland |

Wales |

Northern Ireland |

North East England |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected age-adjusted health spending per person | £2,179 | £2,252 | £2,102 | £2,212 |

| Actual health spending per person, 2018/19 | £2,305 | £2,269 | £2,300 | £2,338 |

| Actual health spending compared to expected age-adjusted spending per person | +5.8% | +0.8% | +9.4% | +5.7% |

Source: Institute for Government analysis.

This suggests that the majority of extra spending in Wales compared to England is explained by its older population, but that Scotland, Northern Ireland and the North East spend more than England even after adjusting for age. In the case of the North East this reflects other factors in England’s internal allocation formula, such as higher rates of disability. As Wales and the North East have similar demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, the gap in age-adjusted spending suggests that if funding were allocated to Wales via England’s formula, Wales would spend around 5% more than it does now.

The independent Holtham Commission assessed overall spending in Wales compared to England in 2010 and found that for health care, Wales had needs 14–15% higher than England,[62] and – across public services – Wales was underfunded relative to estimated needs.[63] The UK government continues to allocate devolved funding through the Barnett formula – which does not consider needs. However, the Welsh and UK governments reached an agreement in 2016 that future funding increases would be 105% of the increase in English spending, with the aim over time of reaching a ‘funding floor’ of 115% of English spending.[64]

The devolved administrations need higher funding to provide the same level of health care as England. An analysis in 2013 applied the health funding allocation formulae of England and Scotland to estimate funding for the four nations,[65] and found that both would allocate more money to the devolved nations than to England.[66] Both formulae would have allocated the most money to the North East among England’s regions, a similar amount to that allocated to Scotland and Wales.

Table 3.3 Estimates of the health care spending needs of the devolved nations and the funding they would receive through the English funding formula

|

|

Scotland |

Wales |

Northern Ireland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average per-person need (index, England average = 100), 2013 | 111.7 | 115.5 | 109.1 |

| Actual spending per person, average 2005/06-2010/11 (index, England = 100) | 113.9 | 107.7 | 108.5 |

Source: Institute for Government analysis of Ball R, Eiser D and King D, ‘Assessing Relative Spending Needs of Devolved Government: The Case of Healthcare Spending in the UK’, Regional Studies, May 2013, p. 11.

If UK health spending had been allocated through the English funding formula in 2013, then Scotland would have received 11.7% more funding per person than England, but Scotland actually spent 13.9% more per person. Higher spending in Northern Ireland (8.5% more than in England) was roughly accounted for by differences in health needs. Wales is a clear outlier. It spent 7.7% more per person than in England, but England’s formula would have given it substantially more – 15.5% more per person.

These calculations are now out of date – spending has increased faster in England than in Scotland since 2013. As of 2018/19, Scotland spends 6.3% more per person than England, Northern Ireland 6%, and Wales 4.6%. An updated calculation would be likely to show that the gap between English formula-assigned spending and actual spending in Scotland has narrowed, and that Wales still spends less than it would receive via England’s formula.

NHS resources

Scotland has the highest staff rates

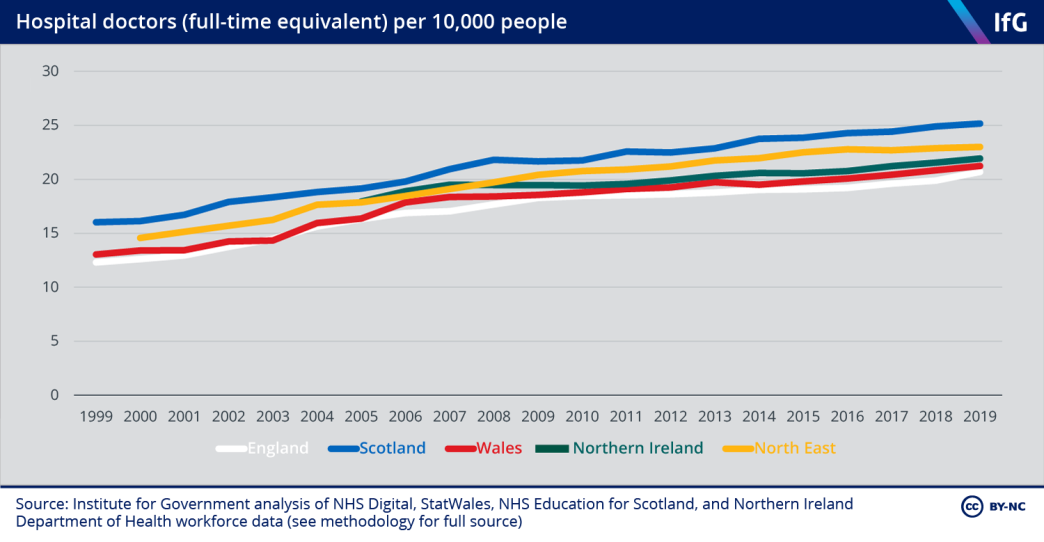

Differences in spending translate into differences in resources – mainly staff and beds.* The number of hospital doctors per person in each nation broadly corresponds to their level of health spending, although the number of doctors per person in England is slightly higher than would be expected for England’s level of spending.

Due to the lack of comparable data on how many hours GPs work, it is not possible to judge which nation has the most extensive primary care. The number of GPs – which cannot account for any differences in how many hours GPs work in each nation – suggests that Scotland has the most GPs per person, and that England and Wales have a similar number per person. Data on the full-time equivalent number of GPs available between 2009 and 2011 also suggests that Scotland had the highest number a decade ago.[67]

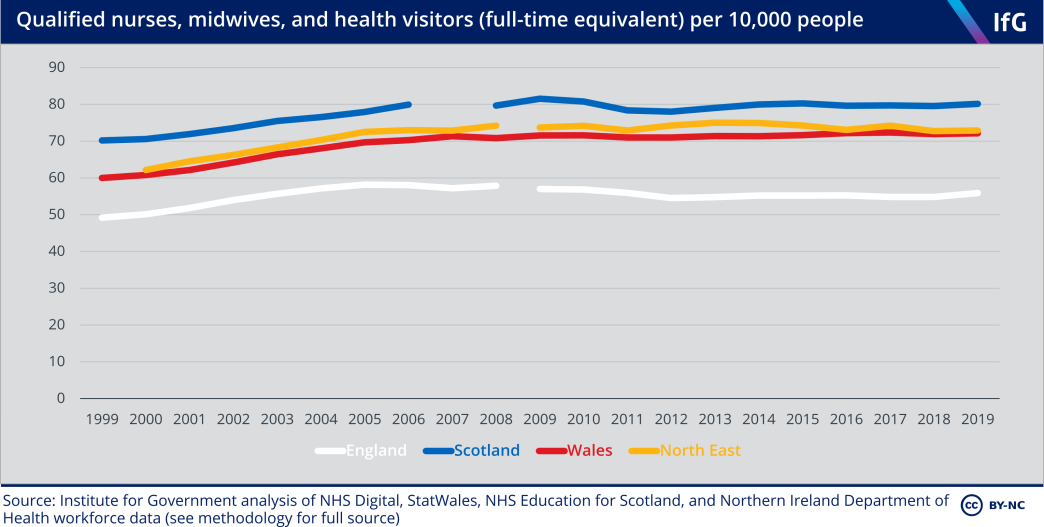

Scotland also has the highest number of qualified nurses, midwives and health visitors per person. The trends in the three devolved nations compared here are again similar, but unlike hospital doctors, there was no increase in the number of nurses during the 2010s. England has significantly fewer nurses – both because of England’s lower spending, and because it relies on support staff, such as health care assistants, more than the other nations.[68]

* Comparing staff numbers and bed numbers is difficult because the four nations define and count these differently so the following data should be interpreted as indicative rather than precisely comparable.

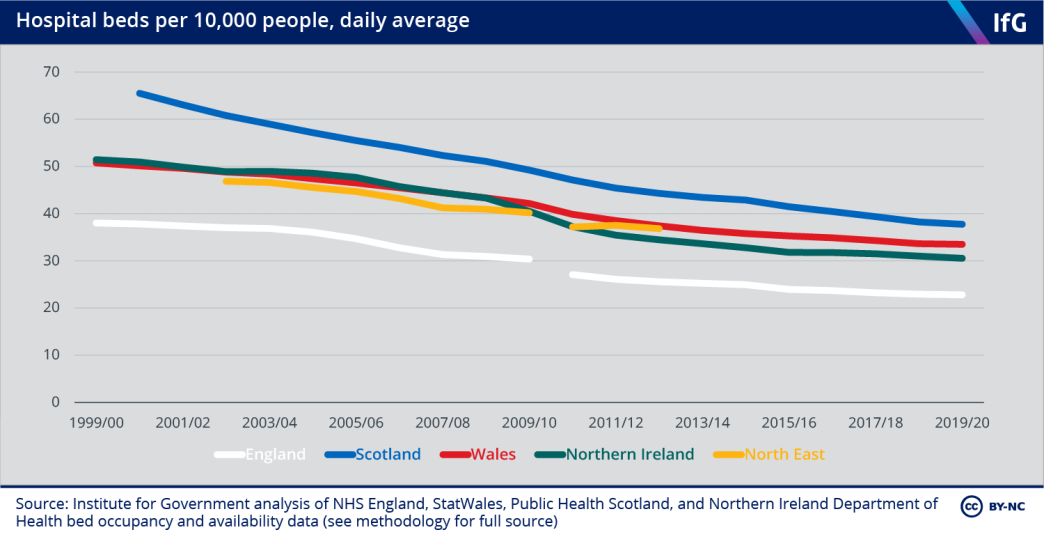

Scotland has the most hospital beds per person

Scotland has consistently had the most hospital beds per person since devolution, and England the lowest. The gradual fall in all four nations reflects medical innovations that have enabled less invasive surgery and shortened recovery time (meaning that hospitals require fewer beds to provide a similar amount of care),[69] and a shared policy of moving care out of hospitals and into community settings where possible.

NHS performance

Comparing the ‘performance’ of health systems – whether the efficiency of the system, the effectiveness of care provided, or how satisfied patients are with the care they receive – is difficult. There is no single objective measure of health performance, and the four nations have prioritised different goals. Some aspects of performance are particularly hard to measure, or to attribute to government policy – it is not clear, for example, whether disability-free life expectancy is an outcome of the health care system, a demand on it, or both. To compare performance, we therefore analyse a variety of indicators primarily attributable to the health system itself and broadly comparable across the four nations, looking at waiting times, patient satisfaction and treatable mortality.

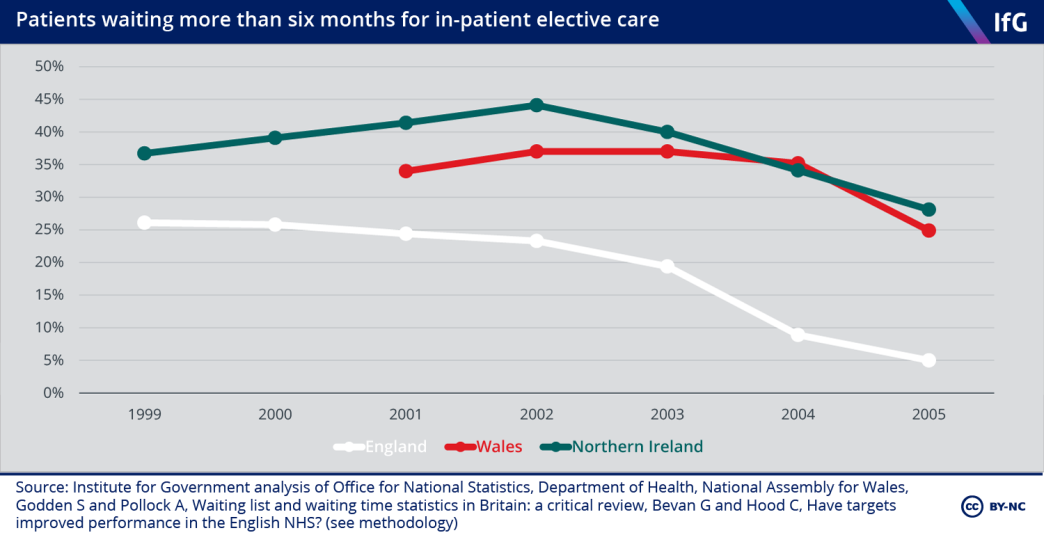

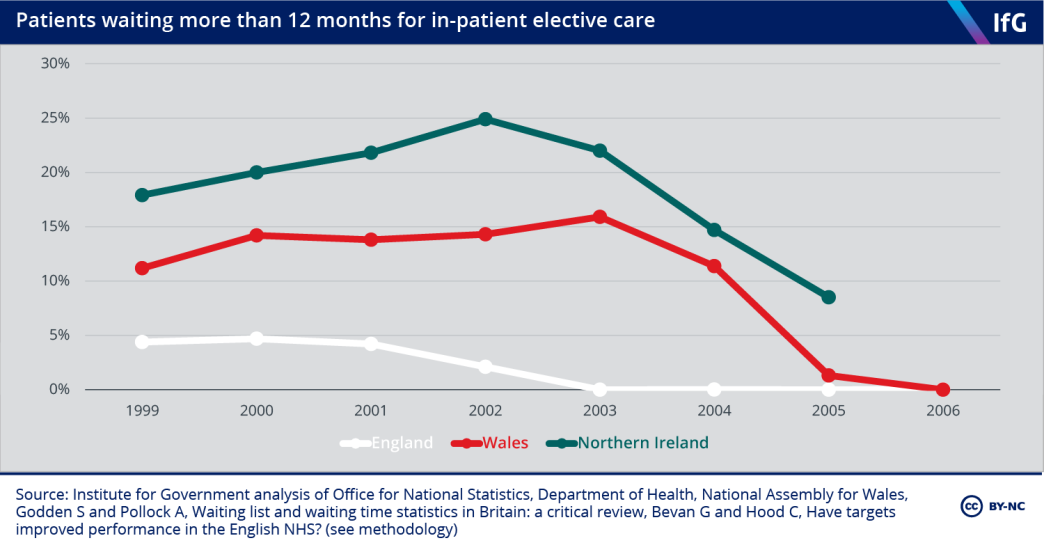

England appears to have reduced elective waiting times fastest in the early 2000s

One measure of the performance of health services is how long people have to wait for treatment.* The first major point of divergence after devolution was England’s ‘targets and terror’ performance management regime, which was not replicated in the devolved administrations. As spending was increasing at a similar rate in all nations, comparing waiting times is a useful way to evaluate how effective that system was. The reported data shows that England improved performance in targeted areas faster than the devolved nations in the early 2000s.

The Blair government prioritised reducing waiting times for elective care in 2000,[70] and between 1999 and 2002 England reduced the number of people waiting more than six and 12 months for inpatient elective care while the number of patients waiting in Wales and Northern Ireland increased. After 2003, both Wales and Northern Ireland started to reduce the number of people waiting although they remained behind England.

Scotland’s waiting times data were measured differently and are not directly comparable – but one analysis comparing the difference in changes in waiting times in England and Scotland between 1997/98 and 2003/04 found that England reduced long waiting times (six months or more) faster than Scotland, by somewhere between 2% and 9%.[71]

The reported data suggests that England’s system helped reduce elective waiting times faster than the other three nations, albeit at the expense of some ‘gaming’ - deliberate actions to improve the reported data.[72] There is some evidence that hospitals in England manipulated waiting list data, and cancelled or delayed follow- up appointments to meet their targets.[73] Approximately 100,000 fewer people were accepted for treatment (put on the waiting list) in the period 2000–03 compared to 1997–99.[74] As it is unlikely that the need for treatment declined significantly between these periods, this suggests hospitals may not have been accepting patients for treatment that they previously would have to reduce waiting lists. England’s system thus had a significant impact on reported performance against targets. Long waits were genuinely reduced – but the exact level of improvement is hard to determine.[75],**

The broader lesson is that targets alone do not necessarily drive improvement. While all four nations had waiting time targets in the early 2000s,[76] only England implemented a linked system of public star ratings, sanctions and rewards. There is some evidence that these star ratings and sanctions – which gave transparent rankings to providers[77] – drove improvement, rather than the targets themselves.[78] There is also evidence from the US and Italy that ‘transparent public ranking’ can improve health care performance[79] – but the system employed in England between 2000 and 2005 involved both this (via star ratings) and sanctions, such as job losses, and it is difficult to disentangle these factors. Targets are not guaranteed to improve performance, and their impact depends on how they are designed and implemented, and the broader system of performance management that they are part of.[80]

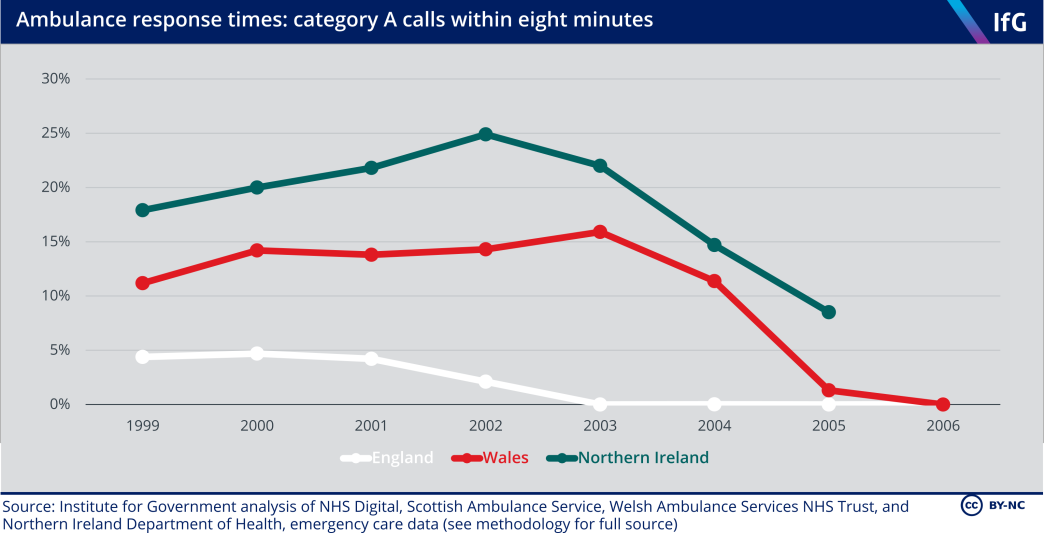

Ambulance response times further illustrate the effect of the star ratings system. England and Wales both introduced call prioritisation in the late 1990s, and both England and Wales had a target to reach 75% of category A (life-threatening) calls within eight minutes by 2001.[81] England improved from 1999/2000 onwards and achieved this target in 2002/03, but performance in Wales hardly improved from 1999/00 to 2003/04.*** The principal difference between England and Wales during this period was England’s star rating system, which applied to ambulance trusts between 2002 and 2005.

As with waiting times, there is also evidence of gaming in England. While ambulance trusts improved performance against the headline eight-minute target, they showed little improvement on non-headline targets.[82] In around a third of trusts, response times were manually ‘corrected’ to be recorded as taking less than eight minutes[83] – although a reanalysis by the Commission for Health Improvement found that “dramatic corrections” to response times would have at most improved reported performance by 6%[84] meaning gaming did not fully undermine improvements.

Scotland and Northern Ireland also improved quickly between 2005 and 2010. Both published performance data during this period and in Scotland, the target gradually increased up to 75% by 2008/09. This was not quite achieved, but the combination of targets and public reporting – such as the Scottish government’s increased focus on HEAT targets – seems to have driven improvement.

In the 2010s, there were frequent changes in measuring ambulance service performance in England, Scotland and Wales, making it impossible to compare. Northern Ireland responded to a smaller proportion of calls on time after 2010 – although the total number of category A calls has been stable since 2014/15, so it is difficult to explain why there has been such a dramatic decline in meeting the eight-minute target. The English, Scottish and Welsh data shows some evidence of a slight decline in the 2010s, but the frequent changes make it difficult to judge accurately.

* Waiting time figures require caution: some of the difference may be because England explicitly targeted this measure of performance and so put more emphasis on reducing waiting times.

** There is little evidence that hospitals hit the targets in England by reducing the quality of other aspects of care such. While England had star ratings, sanctions and rewards, there was no rise in hospital mortality in hospitals in England compared to hospitals in Wales and Scotland. See Besley T, Bevan G and Burchardi K, ‘Naming and shaming: the impacts of different regimes on hospital waiting times in England and Wales’, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Discussion paper 7306, 2009, retrieved 11 February 2021, pp. 13–15, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/33775.

*** The Welsh government responded to the ambulance service’s underperformance by reducing the target to 65% in 2004.

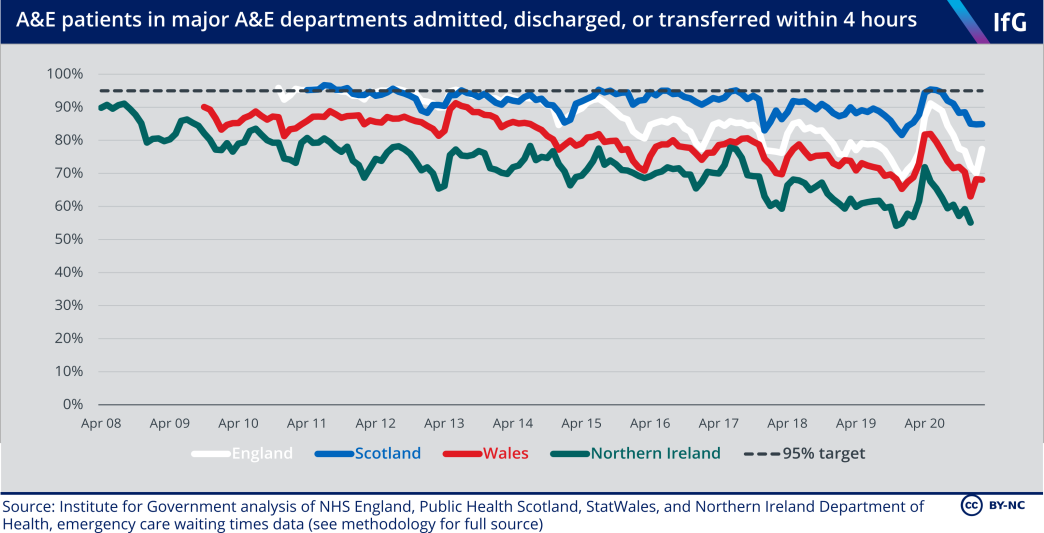

Scotland now sees the most emergency department patients within four hours

All four nations have had a long-standing target that 95% of A&E patients should be admitted, discharged or transferred within four hours. Scotland has had the best A&E performance on this measure of the four nations since 2015; Northern Ireland has consistently had the worst. The trends in the four nations are very similar: a gradual but consistent decline during the 2010s, at least partly explained by tight funding.[85] The uptick at the start of 2020 is due to much lower A&E attendance during the early months of the coronavirus crisis when, even before the first national lockdown was introduced, many people chose to stay away from hospitals.[86]

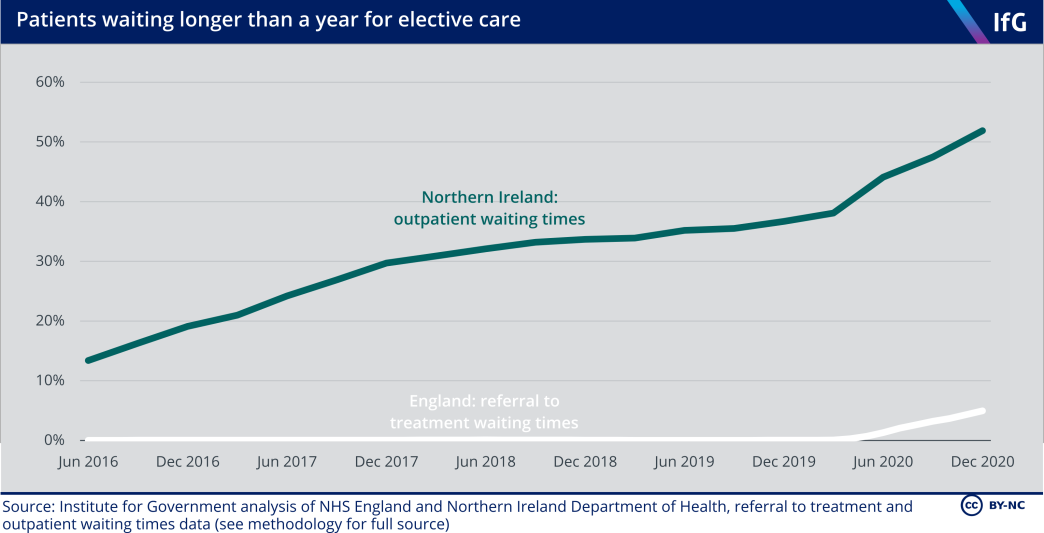

Northern Ireland has the longest elective waiting times in the UK

It is difficult to compare waiting times for elective care in the four nations because the data is not collected and published in a comparable way,* but it is clear that waiting times in Northern Ireland are much longer than in any of the other three nations. Northern Ireland measures two different waiting times: outpatient waiting times (the time patients wait from being referred to having their first outpatient appointment), and inpatient waiting times (the time patients wait from when a clinician decides they need treatment to being treated).

Comparing referral to treatment times in England – which cover both outpatient and inpatient waiting – to just outpatient waiting times in Northern Ireland is illustrative. Between 2016 and 2019 virtually no patients in England waited longer than a year from referral to treatment – in Northern Ireland, a large proportion of patients had to wait longer than a year just to receive their first outpatient appointment. Over a third of patients on outpatient waiting lists in Northern Ireland were waiting for more than a year before the coronavirus pandemic.

Northern Ireland also has very long inpatient waiting times, meaning patients wait even longer once a clinician has decided they need treatment; some wait years from referral to treatment.[87] The comparison with England is stark. In September 2019, more than 100,000 patients had waited more than a year for their first outpatient appointment in Northern Ireland, whereas in England only 1,305 patients had waited more than a year on the entire pathway from referral to treatment, even though Northern Ireland has only 3.4% of England’s population.[88]

The number of people waiting for a long time in Northern Ireland has increased since the 1990s. Waiting times decreased in the mid-2000s but these gains were lost within a few years,[89] and the number has increased since 2013. Between December 2013 and December 2018 there was a 459% increase in the number of patients waiting more than nine weeks for their first outpatient appointment.[90]

There are multiple causes of Northern Ireland’s long waiting times, but insufficient funding and rising demand are not plausible explanations. Northern Ireland’s health spending is comparable to Scotland and Wales, and elective waiting time performance has been stable in Wales during the 2010s.[91] There have been year-on-year increases in elective care referrals in all four nations of the UK.[92] Plausible explanations include: increases in emergency admissions (forcing hospitals to postpone elective procedures),[93] inefficiencies in hospital provision (Northern Ireland has an excess of acute hospitals and a lack of specialist sites, slowing down treatment times as resources are spread thinly),[94] staffing shortages, and ineffective performance management (none of Northern Ireland’s waiting time targets has been met since 2014 despite regular changes to make the targets easier to achieve).[95],[96]

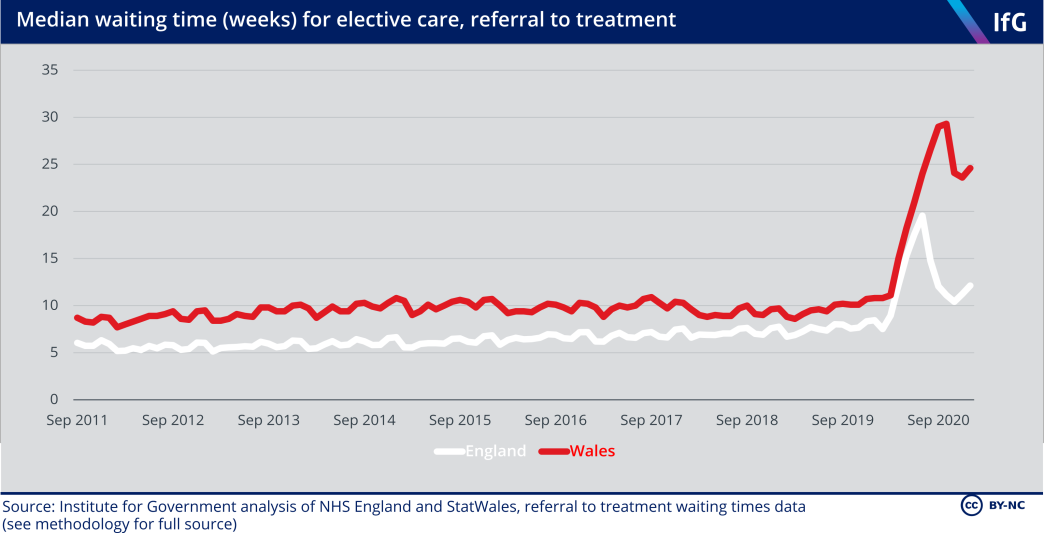

Comparing the nations in the rest of the UK** shows that throughout the 2010s England had shorter median waiting times than Wales, although waiting times in Wales did not increase over the decade, whereas waits got slightly longer in England.*** The trend in Scotland’s elective waiting times is similar to England between 2012 and 2020, showing slightly lengthening waiting times.****

* England, Scotland and Wales all measure the time from ‘referral to treatment’ (RTT) – the time that non- emergency patients wait between first being referred to starting treatment. However, it is only possible to fairly compare England and Wales because they both publish data on ‘incomplete’ waiting times – the length of time patients who are currently on the waiting list have been waiting.

** Scotland publishes data on complete referral to treatment times (people who have been treated), whereas England and Wales publish data on incomplete referral to treatment times (people who are waiting to be treated) – and is not included here. The implications for comparison are unclear: international evidence suggests that waiting times for patients treated may be longer or shorter than waiting times for patients on waiting lists. See Siciliani L, Moran V and Borowitz M, ‘Measuring and comparing health care waiting times in OECD countries’, Health Policy 118(3), December 2014, pp. 292–303, retrieved 3 March 2021, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/82804797.pdf

*** The rapid increase in waiting times in England and Wales after March 2020 reflects postponed operations as a result of the pandemic response.

**** As measured by patients waiting longer than 18 weeks for incomplete RTT (England), compared to patients waiting longer than 18 weeks for complete RTT (Scotland).

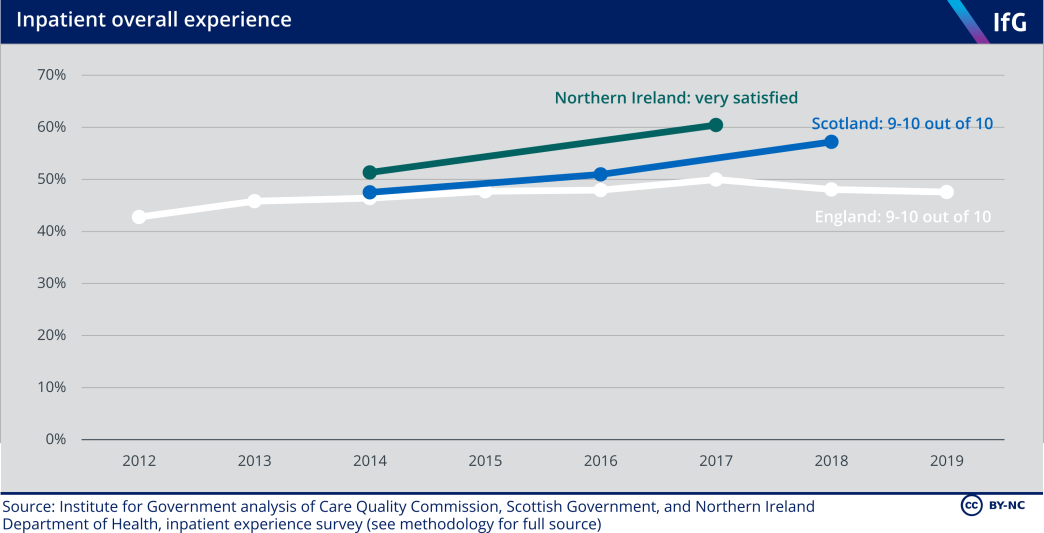

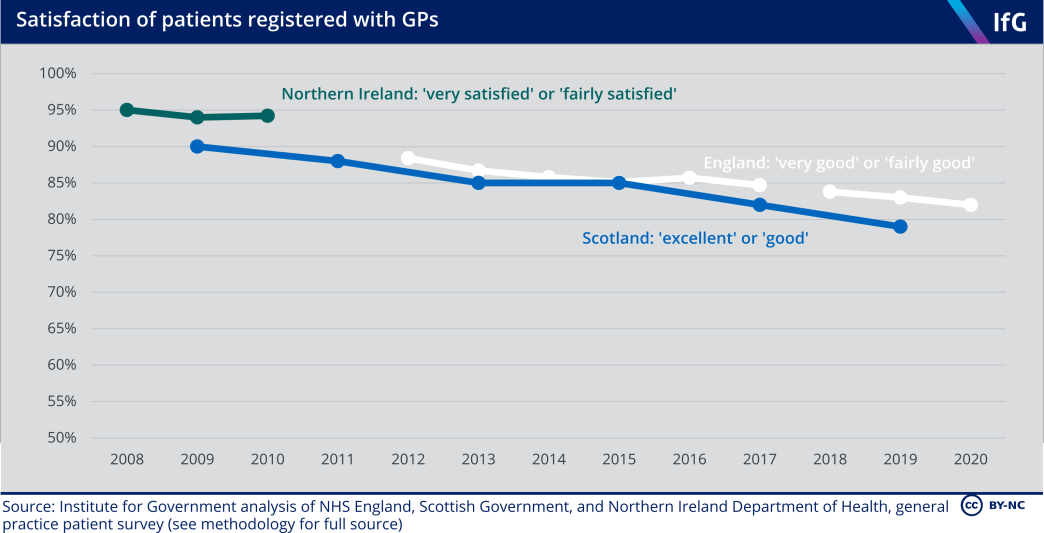

Patient surveys suggest similar levels of satisfaction

Patient experience surveys provide another measure of performance. Differences in survey design mean that only England and Scotland – who ask inpatients to fill in surveys rating their “overall experience” on a scale of 1–10 – can be easily compared. Inpatient surveys suggest that patients in England and Scotland are broadly equally satisfied, although patients in Scotland reported being more satisfied in 2018.

Northern Ireland also asks a question about “overall experience” but uses a five-point scale. The proportion who are “very satisfied” is, however, relatively similar to the proportion who choose 9–10 out of 10 in Scotland and England. Wales does not have a comparable inpatient survey.

England and Scotland also run similar general practice satisfaction surveys – both ask patients registered with GPs to say how satisfied they are on a five-point scale, albeit with slightly different wording.* Patients’ satisfaction with their GP is similar in both countries, declining during the 2010s. The limited data from Northern Ireland only shows that satisfaction was high between 2008 and 2010. Wales uses a different survey methodology, so the results are not comparable.

* There was a methodology change in England in 2018.

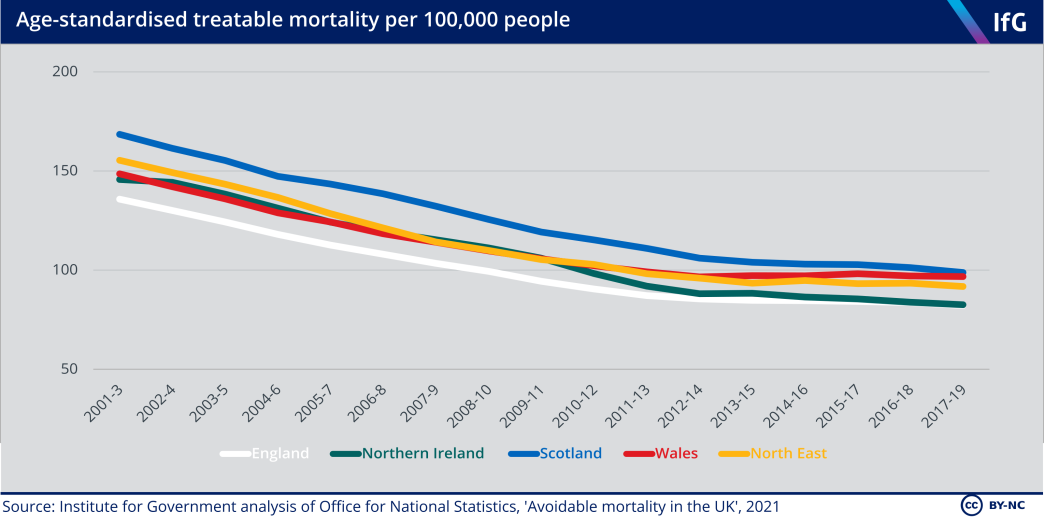

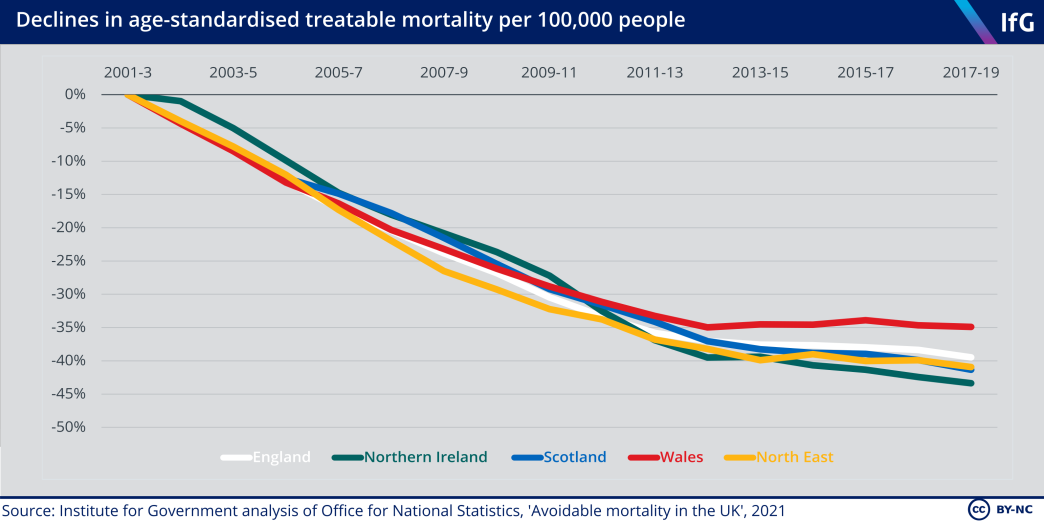

The four nations of the UK have all reduced treatable mortality since devolution

It is difficult to measure the impact of health care systems on overall population health, but ‘treatable mortality’ approximates how much health care reduces mortality. Treatable mortality measures “causes of death that can be mainly avoided through timely and effective health care interventions, including secondary prevention and treatment”,[97] and is often used as a way to assess the quality of care in different systems across countries and over time.[98] Deaths caused by appendicitis, scarlet fever and asthma are considered treatable, but deaths caused by malaria, influenza (flu), and alcohol and drug poisonings are instead considered preventable – “deaths that can be mainly avoided through effective public health and primary prevention interventions”.*

Some causes of death are counted as 50% treatable, to reflect that some cases are treatable while others are not, so some cancers and heart disease are included. Owing to the difficulty of assigning causes of death for older people, treatable deaths only include those aged under 75. In 2019, 8% of all deaths in the UK were considered treatable.[99]

Treatable mortality is a subset of overall mortality, which partly explains why Scotland which has higher overall mortality rates – has consistently had the highest rate of treatable mortality since 2001.**

The four nations have reduced treatable mortality at similar rates since devolution, despite their very different starting points and divergent policy choices – principally because of developments in medical science and treatment common to all four nations. As with overall mortality, the rate of improvement has slowed since 2011 although Northern Ireland – despite poor health service performance on the measures detailed above – continued to improve during the 2010s, such that it is now very similar to England on this measure.

Northern Ireland has improved the most since 2001, and Wales the least. In Wales in the 2010s, treatable mortality among both men and women barely improved. England and Scotland have improved at similar rates. Given the demographic comparability between the North East of England and the devolved nations described above, improvements in treatable mortality among men in the 2000s suggested that England’s health care system was initially improving faster[100] – but Scotland and Northern Ireland have improved more than the North East in the 2010s.

Looking at causes of death, the difference between Northern Ireland and Wales is mainly accounted for by deaths caused by circulatory diseases, such as aneurysms and heart disease, and deaths caused by respiratory diseases, such as asthma and pneumonia. Deaths from circulatory and respiratory diseases are significantly higher in Wales than in Northern Ireland, and Scotland also has high deaths from circulatory diseases.[101]

Considering Northern Ireland’s very long waiting lists for elective care, it is surprising that it performs well as measured by treatable mortality. This is probably because long elective waits tend not to be for life-saving procedures. Some studies suggest that long elective waiting times – which in most cases are for procedures to improve mobility or reduce pain – are associated with reduced quality of life, but not higher mortality rates.[102] Monitoring the clinical impacts of long elective waiting times appears to be inadequate in both Northern Ireland and England,[103] and further research in this area would help inform future policy.

Higher treatable mortality rates in Wales might be linked to Wales’s low spending compared to need in the 2010s, but Wales’s relatively high treatable mortality rate in the 2010s is likely to have a variety of causes.

* Treatable mortality does not, for example, cover vaccination to prevent contagious diseases. Bevan and others (2014) found that childhood vaccination rates in 2011/12 were very similar in the four nations, with England’s vaccination rates slightly lower than the other three nations. For a full list, see OECD, ‘Avoidable mortality: OECD/Eurostat lists of preventable and treatable causes of death (November 2019 version)’, November 2019, retrieved 6 April 2021, www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Avoidable-mortality-2019-Joint-OECD-Eurostat-List-preventable-treatable-causes-of-death.pdf

** Scotland’s significantly higher drug and alcohol deaths are not included in this comparison because they are considered ‘preventable’ rather than ‘treatable’. In 2019, there were 48.1 alcohol- and drug-related deaths per 100,000 people in Scotland, significantly above Northern Ireland (31.7) and more than double Wales (23.9) and England (21.4). See ONS, ‘Avoidable mortality in the UK: 2019’, ONS, 26 February 2021, retrieved 6 April 2021, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/datasets/avoidablemortalityintheuk

Lack of comparable data prevents a more complete assessment of performance

Almost all attempts to analyse performance in the four nations of the UK have found serious problems when comparing the data produced by each nation owing to variations in data collection and publication. We encountered the same problem in our research: there is not enough comparable data to build a clear picture of the performance of the four health care systems.

Improving data is vital to widening our understanding of the health systems in the four nations, and to shed greater light on the successes and failures of different policies. This should be a priority for both statisticians and policy makers. Better data will help policy makers improve services. We recommend that the following data should be prioritised for improvement:

- Hospital activity: it is difficult to compare hospital activity data – the number of inpatients, outpatients, day cases and procedures in each nation. These are vital to compare productivity and efficiency. While the problems are well known,[104] little has been done to improve comparability.

- Spending: more granular spending data would be useful to evaluate how the four nations spend their health budgets – distinguishing between hospital and community health services, primary care and social care.

- Staff: the way that doctors and nurses are counted in each nation is still slightly different, without good reason. We think that statisticians in the four nations should explain why staff are counted differently and agree a methodology to collect data on the number of hours worked by GPs, to allow meaningful comparison.

- Elective waiting times: the four nations still count waiting times differently, although England and Wales now produce data on the time taken from referral to treatment, including median waiting times for people currently waiting for treatment. Scotland and Northern Ireland could adopt this measure – or England and Wales could publish comparable data on people who have been treated. The health systems in England, Scotland and Wales should have the underlying data to publish either or both of these measures, and it would increase accountability if they agreed to publish at least one – ideally both – comparable measure regularly. Northern Ireland should prioritise producing data on the time from referral to treatment both to improve policy makers’ understanding of how long patients wait in total, and to facilitate accurate comparisons with the other three nations. Before the pandemic, there was ongoing work in Northern Ireland to produce referral to treatment waiting times, and we strongly recommend that data comparability should be considered as this is developed.[105]

- Experience surveys: the four nations should agree a single question for inpatient and GP experience in their health surveys, to allow comparison using the same wording and answer scale. England and Scotland already have very similar questions, so this could provide a starting point. The four nations should also use a similar methodology for these surveys.

The social care systems of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland provide different levels of care.

Adult social care

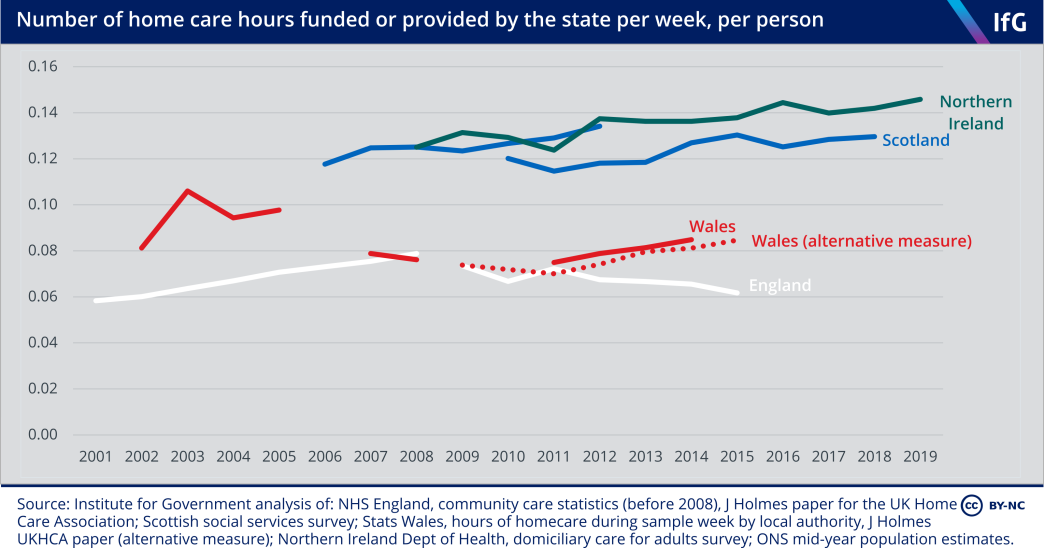

The social care systems of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland provide different levels of care. Proportionally, nearly twice as many older people receive care at home or in a care home in Northern Ireland than in England, and all three devolved governments spend more on care than in England.

Differences in spending reflect differences in policy: Scotland and Northern Ireland spend more because they have chosen to provide some free home care to all people in need, not just those who pass a means test.*

But all four social care systems have been squeezed in recent years, as spending has not risen in line with demand. This has blunted the impact of those policy differences, as providers in all four countries have used similar strategies to manage demand locally.

It is not possible to say which social care system performs best. The four governments measure very few social care outcomes, and those that they do measure are difficult to compare. This lack of information has hindered governments in the four nations from learning from each other’s experiences in order to improve services. Improving data availability and comparability must be a priority.

* Home care refers to care provided in a person’s own home – for instance, washing, managing medication, or helping with routine household tasks. Northern Ireland provides free home care, whereas Scotland provides free personal care, a term that encompasses most aspects of home care but excludes some household tasks like meal preparation. Residential care refers to care provided in a care or nursing home. Nursing care means care services that need to be provided by a trained nurse, usually for higher-need clients.

Social care policy

Scotland and Northern Ireland gained legislative powers over social care in 1998 and Wales in 2006.[1] Since then, the four nations have made different policy choices, notably on which services are available for free.

Most of the differences between the systems are the result of choices made since devolution. But some elements of social care provision, like the administrative integration of health and social care in Northern Ireland in 1973 or differences in whether services are provided by the private or public sector, pre-date devolution.

England’s system is the least generous

The proportion of people whose care is paid for by the state is very different in different parts of the UK, due both to variation in policy design and to differences in wealth between the four nations.[2]

Table 4.1 Summary of state-funded social care in the four nations

Country |

Means test (upper limit)* |

Responsible body |

Non-means- tested provision |

% self- funding – home care |

% self- funding – residential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | £23,250 | Local authorities | Limited NHS provision** | 30% | 46% |

| Scotland | £28,000 | Local authorities | Free personal and nursing care | 25% | 36% |

| Wales |

£50,000 (residential) £24,000 (home care) |

Local authorities | Capped home care costs (£100 per week) | 21% | 32% |

| Northern Ireland | £23,250 | Health and social care trusts | Free home care and nursing care | 7% | 11% |

Source: Institute for Government analysis of self-funding estimates from the Skills for Care papers in the four nations, means test limits from Oung C, Schlepper L and Curry N, ‘Offer and eligibility: Who can access state-funded adult care and what are people entitled to?’, 18 March 2020, retrieved 1 April 2021, www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news- item/offer-and-eligibility-who-can-access-state-funded-adult-care-and-what-are-people-entitled-to***

To receive state-funded care, potential users are assessed to see if they need support, and if the value of their assets is below a given threshold.**** In all four nations, those who meet the relevant needs and means test receive state-funded care – such as home adaptations, home care or a care or nursing home place. For those who meet the means test, the state provides the full costs of staying in a care home – covering both care and so-called ‘hotel costs’.*****

Wales has the most generous means test, providing funding for residential care to anyone in need with assets valued at under £50,000. The threshold for residential care was raised from £24,000 in 2017; the means test for community care remains £24,000.[3] Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland provide some state-funded care even for those who have assets above the threshold. In Wales, those with a higher level of assets have their contribution to home care capped at £100 per week.[4] In Scotland and Northern Ireland, most care services provided in the home are free, regardless of the assets someone has. In Northern Ireland, health and social care trusts (HSCTs) have the right to charge for home care services but rarely do, and never charge the over-75s.[5]

In Scotland, personal care has been free since 2002 for people aged 65 and older, and since 2019 for all adults.

In Scotland and Northern Ireland, the state also provides a subsidy for care and nursing home residents who are in need, but those with assets above the means test must continue to pay the majority of their fees.

* Those with assets above this level have to fund all of their care themselves. There is also a lower means test limit, below which all care is state-funded. For those whose assets fall between these two limits, the state will fund part of care costs, depending on the income and the assets of the care recipient.

** NHS Continuing Care funding – through which the NHS pays for the care of those whose needs are primarily health needs – funds around 10% of residential care beds in England.

*** A ‘self-funder’ is someone who primarily pays for their own care out of a pension, savings or other assets, rather than receiving government support. Many care recipients, including those in residential care in Scotland who receive free personal care payments from the government, fund only part of their care, so these self-funding estimates include everyone who is fully or mainly self-funding.

**** Needs tests vary between nations in terms of what services applicants are entitled to receive. Means tests do not take into account the value of a home when care recipients or family members still live there, so in most cases only financial assets like savings, pensions or second homes are included. The Money Advice Service, ‘Means tests for help with care costs – how they work’, [no date], accessed 1 April 2021, www.moneyadviceservice.org.uk/en/articles/means-tests-for-help-with-care-costs-how-they-work

***** ‘Hotel costs’ are the costs charged for the accommodation and food provided by care homes and nursing homes, which typically make up most of care home fees.

Northern Ireland is unusual in funding and administering health and social care together

Social care services are run by local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales. The services are therefore run separately from the NHS, although people frequently move between hospitals and care settings.