Towns Fund

The Towns Fund for England (hereafter the Towns Fund) is a £3.6 billion fund for ‘struggling’ towns across England to support local economic growth.

What is the Towns Fund and how has the money been allocated?

The Towns Fund for England (hereafter the Towns Fund) is a £3.6 billion fund for ‘struggling’ towns across England to support local economic growth.[1] The Towns Fund was announced in July 2019 and incorporated the £1.6 billion Stronger Towns Fund announced in March 2019.

The Towns Fund has three separate funding strands:

- Funding for 101 towns invited by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC, formerly the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government) to submit bids. These towns could submit bids for up to £25 million each, or up to £50 million in exceptional circumstances. The selected towns were not automatically eligible for funding but their proposals were to be evaluated by DLUHC. A full list of the funding allocated was published in July 2021, and the amount allocated came to £2.3 billion in total.[2]

- A competitive allocation of funding for further towns that were not initially selected. DLUHC has committed to making this funding available in future but has not yet provided any details of how it will be allocated.[3]

- The future high streets fund, £830 million for regenerating high streets across England in December 2020 and May 2021. The process of selection for this fund was separate from the towns deal process – any local area (including London boroughs) could bid, though DLUHC’s prospectus stated that bids should only be from areas ‘facing significant challenges’.[4] In May 2021, DLUHC confirmed 57 of the 72 high streets that will win funding. 16 of those 57 were also towns that were invited to bid for town deals.

This explainer focuses on the first strand of funding: the selection of towns and the allocation of money for Town Deals.

How were towns initially selected?

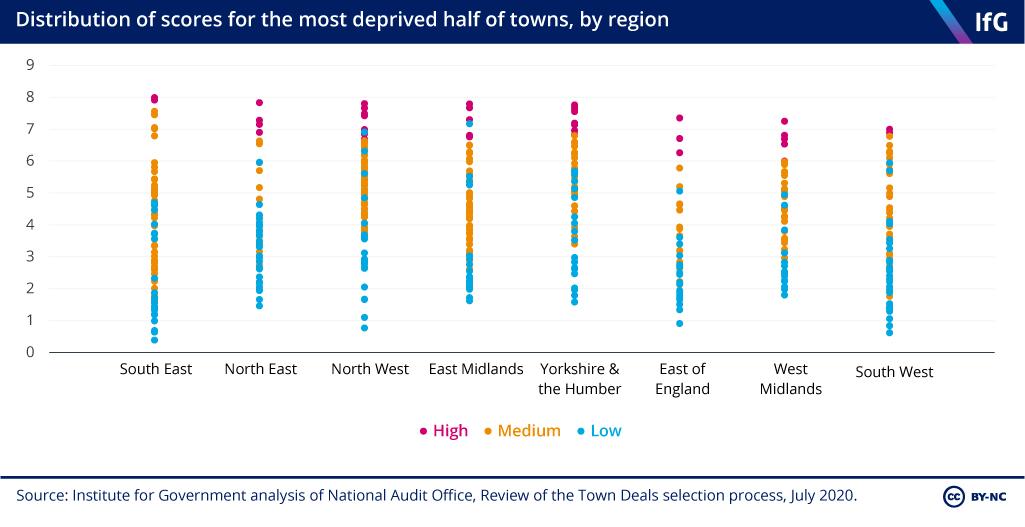

Following criticism that the process of selecting towns to bid for Town Deals was biased,[5] the National Audit Office published details of the full selection process.[6] Officials at DLUHC ranked all 1,082 towns in the UK – defined as built-up areas with a minimum area of 20 hectares (200,000 m2), with individual settlements separated by at least 200 metres, and with a population between 5,000 and 225,000 – based on income deprivation. The least deprived towns, 50% of the total, were then ruled out of eligibility for the Towns Fund.

The remaining half were scored and ranked according to a formula that incorporated seven different criteria, summarised in the table below. The first four are quantitative measures drawn from official statistics, while the remaining three are qualitative assessments made by officials at DLUHC.

| Metric | Measure | Sources | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income deprivation | Income component from the Index of Multiple Deprivation | DLUHC and Office for National Statistics (ONS) | 3 |

| Skills deprivation | Proportion of the working-age population with no qualifications at National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) level | ONS | 1 |

| Productivity | Gross value added per hour worked | ONS | 1 |

| EU exit exposure | Gross value added of sectors identified as ‘at risk’ by the Bank of England in the case of a ‘no deal’ EU exit | DLUHC, ONS and the Bank of England | 1 |

| Exposure to economic shocks | Significant economic shocks in the town’s recent history (qualitative) | DLUHC | 1 |

| Investment opportunity | Opportunity for investment signalled by significant current or upcoming private investment (qualitative) | DLUHC | 1 |

| Alignment to wider government intervention | The presence of other government funding or programmes which could complement the Towns Fund (qualitative) | DLUHC | 2 |

Officials also recommended that ministers select different numbers of towns from each of the eight English regions to ensure that funding was spread across the country while still recognising that there are different levels of need in each region. This was based on each region’s productivity, income, skills, deprivation and rural/urban classification (with rural areas assumed to have greater need). The recommended area allocations are summarised in the table below. Officials recommended that 100 towns be selected in total.

| Regions | Recommended number of towns |

|---|---|

| North West | 21 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 19 |

| West Midlands | 18 |

| East Midlands | 14 |

| North East | 11 |

| East of England | 6 |

| South West | 6 |

| South East | 5 |

Officials sorted the 541 eligible towns into high-, medium- and low-priority groups. Officials picked a set of towns in each region (equal to 40% of the number of recommended towns within that region) to classify as high priority. These were towns with the highest total scores on the ranking formula within each region, that scored highly across most criteria, and whose ranking and scores did not significantly change with different weightings of the ranking formula. This resulted in a list of 40 high-priority towns in total, and officials recommended that ministers select all of these towns to be part of the final list of 100.

Towns were classified as low priority either because they were among the 15% of lowest-scoring towns in each region or because they had fewer than 15,000 inhabitants (or fewer than 10,000 in the South West). There were 183 low-priority towns.

The remaining 318 towns were designated as medium priority. Officials recommended that ministers select up to 60 medium-priority towns, depending on how many low-priority towns they also chose. Officials did not recommend that ministers rule out all low-priority towns, but did suggest that ministers choose relatively few of them and record a strong rationale for any selected.

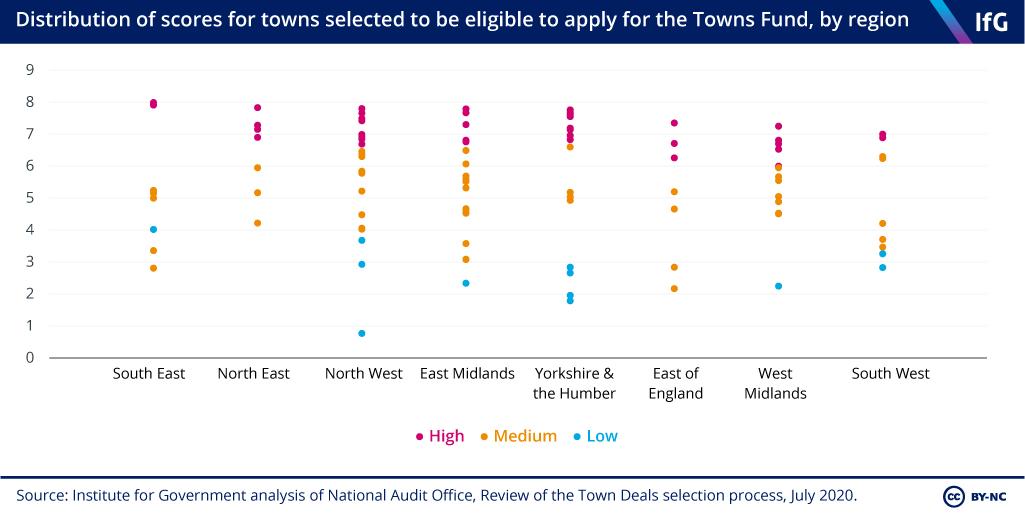

Ministers ended up selecting 101 towns, rather than the recommended 100: 40 high-priority, 49 medium-priority and 12 low-priority. The towns from the medium and low-priority groups that were selected had a range of scores; they were not just the top-scoring of the towns in those groups.

The lowest-scoring town selected was Cheadle, which ranked 535th in the country and last in its region based on the Towns Fund formula. The 12 low priority towns are listed in the table below.

| Town | Region | Overall rank (out of 541) |

|---|---|---|

| Newhaven | South East | 283 |

| Southport | North West | 324 |

| Glastonbury | South West | 363 |

| Leyland | North West | 391 |

| Todmorden | Yorkshire and the Humber | 401 |

| St Ives (Cornwall) | South West | 404 |

| Stocksbridge | Yorkshire and the Humber | 418 |

| Stapleford | East Midlands | 447 |

| Redditch | West Midlands | 454 |

| Brighouse | Yorkshire and the Humber | 482 |

| Morley | Yorkshire and the Humber | 494 |

| Cheadle | North West | 535 |

Ministers had to give specific justifications for any of the low priority towns chosen, examples of which include:

- regeneration and investment opportunities

- levels of income deprivation

- poor transport links

- achieving a spread of towns across a region.[7]

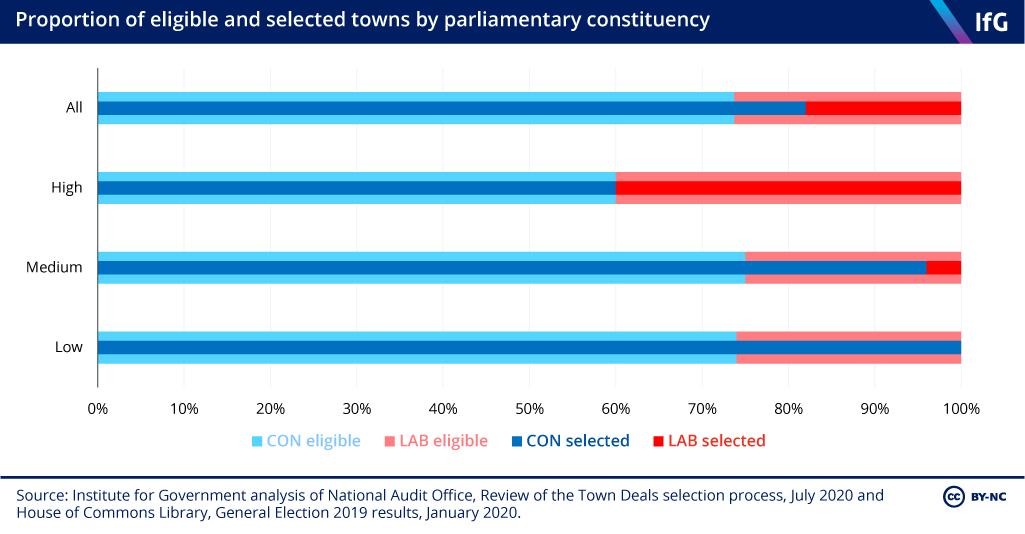

All 12 of the low priority towns selected were in Conservative-held parliamentary constituencies; of all the 183 low priority towns initially eligible, 136 were Conservative, 46 Labour and 1 Liberal Democrat. Figure 3 shows in more detail how across the medium and low priority categories, ministers tended to choose towns in Conservative-held constituencies more than Labour ones – though towns in Labour-held constituencies made up a smaller proportion of the overall towns eligible.

How much money did each town get?

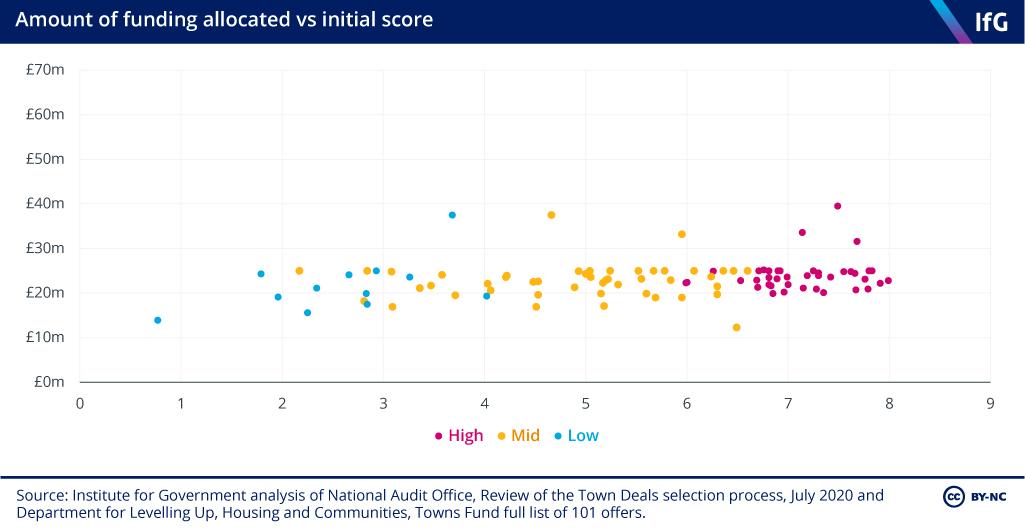

The government published the full list of funding allocations for the Towns Fund in July 2021. In total, £2.3 billion has been allocated to Town Deals. Two towns (Kirkby and Sutton in Ashfield) submitted a joint bid, and so there were 100 allocations in total. The average amount awarded was around £23 million, with the highest award being £62.6 million for the joint bid.

Excluding the joint bid, there were seven towns that received more than the £25 million that was on offer for town deals except for in ‘exceptional circumstances’,[8] as summarised in the table below.

| Town | Region | Total funding allocated |

|---|---|---|

| Blackpool | North West | £39.5 million |

| Southport | North West | £37.5 million |

| Stevenage | East of England | £37.5 million |

| Keighley | Yorkshire and the Humber | £33.6 million |

| Bishop Auckland | North East | £33.2 million |

| Rotherham | Yorkshire and the Humber | £31.6 million |

| Staveley | East Midlands | £25.2 million |

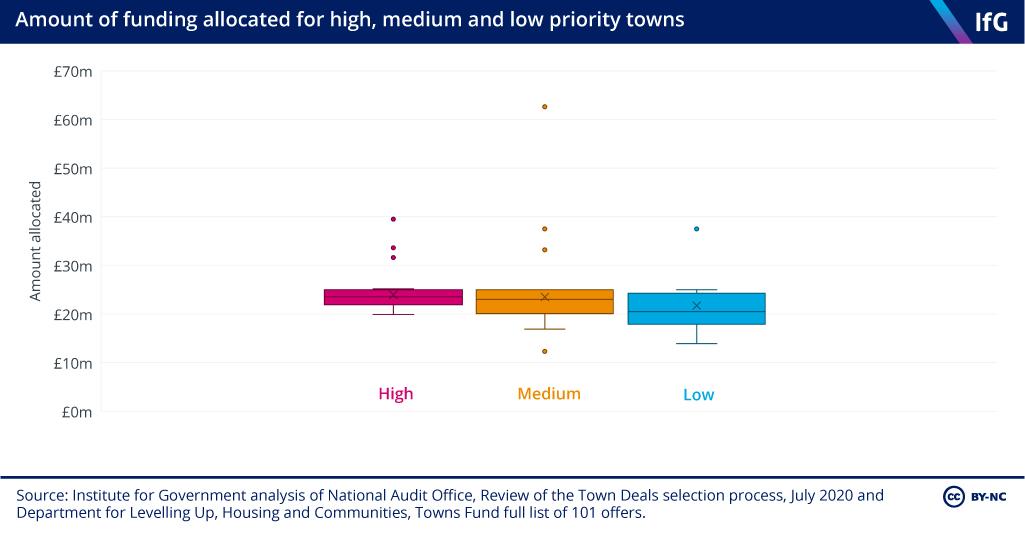

As Figures 4 and 5 show, a town’s score in the initial selection process does not seem to have had much of an effect on the total amount of money it was allocated.

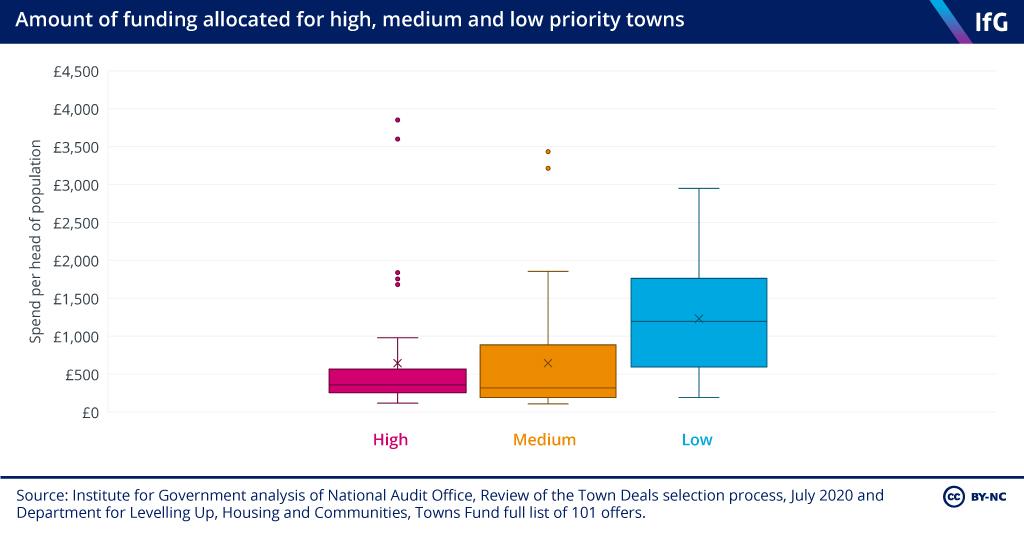

Where there is a more pronounced difference is the amount of funding each town received per head of population. Low priority towns on this measure received more money than those classed as medium and high priority, as shown in Figure 6.

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/924503/20191031_Towns_Fund_prospectus.pdf p. 5

- www.gov.uk/government/publications/town-deals-full-list-of-101-offers

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/924503/20191031_Towns_Fund_prospectus.pdf p. 17

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/783531/Future_High_Streets_Fund_prospectus.pdf

- www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-54894221

- www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Review-of-the-Town-Deals-selection-process.pdf

- www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Review-of-the-Town-Deals-selection-process.pdf p. 27

- www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Review-of-the-Town-Deals-selection-process.pdf p. 4

- Topic

- Public finances Devolution

- Keywords

- Levelling up Regional economic growth

- United Kingdom

- England

- Publisher

- Institute for Government