The levelling up white paper one year on: progress on devolution but big tests to come

The next month will be a crucial test of the government’s ability to deliver the levelling up white paper’s devolution vision.

The next month will be a crucial test of the government’s ability to deliver the levelling up white paper’s devolution vision, write Akash Paun, Peter Hourston and Duncan Henderson.

It is now a year since the government’s Levelling Up the United Kingdom white paper was published. At the time, the Institute for Government welcomed the devolution proposals as “genuinely radical” in their ambition. And since then – despite the political and economic turmoil of 2022 – the government has made reasonable progress toward its commitment that “every part of England that wants one will have a devolution deal” by 2030.

Ministers have now concluded negotiations to devolve power to York and North Yorkshire, the East Midlands, the North East (expanding the existing North of Tyne deal), Suffolk, Norfolk, and Cornwall. In all these cases, local leaders have agreed to adopt a directly elected mayoral model, at either regional or county level, in exchange for powers over transport, skills, housing and other functions. Negotiations are also under way to strengthen the metro mayors of Greater Manchester and West Midlands, and there are plans for a new wave of deals elsewhere in England.

But while these developments are welcome, there remains much to do for the government to deliver the rebalancing of power it has promised, and which it rightly regards as key to achieving its wider levelling up objectives.

The deals still need to be ratified – this is not guaranteed

Concluding negotiations is a significant step towards devolution, but implementation cannot be taken for granted. All deals require public consultation and local council agreement before powers (and money) are formally transferred, and several proposed deals have previously fallen late in the process.

In 2016, for instance, devolution to the North East, East Anglia and Greater Lincolnshire collapsed after councillors voted against implementation, primarily due to opposition to the mayoral model. Scepticism toward mayoral devolution remains widespread within local government, and this feature of the agreed deals may prove a stumbling block once again. Cornwall Council, for example, has already indicated it may put the proposals to a referendum after the public consultation process is completed.

The government and local leaders may therefore face a challenge in persuading councils that the extra freedoms and funding on offer makes the introduction of an elected mayor worthwhile. It will also need to support local areas to develop the necessary institutional capacity to take on responsibility for big skills, transport and infrastructure budgets.

Even if all the new deals get implemented, devolution across the whole of England is a long way off

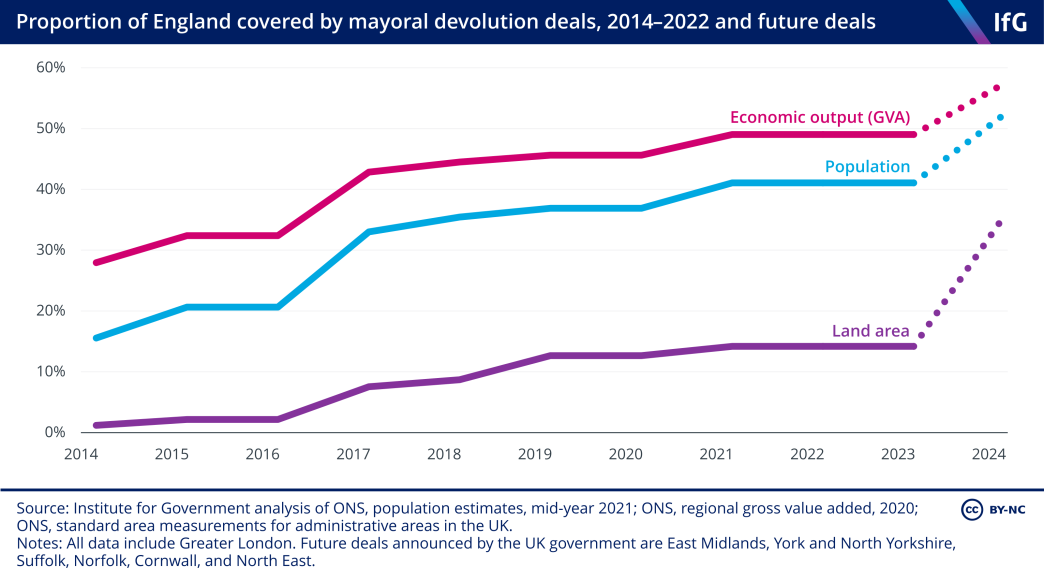

The proportion of England covered by devolution deals has gradually increased since 2014. If all the negotiated deals are implemented, 36% of England’s land area, 52% of the population, and 58% of its economic output will be covered by devolution.

This will be a significant achievement, but it raises the question of what should happen to the rest of the country. The government must also plan for the next wave of deals, and it was welcome to hear levelling up secretary Michael Gove announce, in late January, that Cumbria, Lancashire, Cheshire and Warrington, and Hull and East Yorkshire are next in the queue.

However, future deals may prove more difficult due to disagreement about the right geography for devolution, and opposition to the mayoral model. Ministers may therefore need to be flexible on the governance question or risk losing momentum. In the white paper, the government stated that non-mayoral devolution was an option, albeit with fewer powers on offer than for places willing to accept a mayor. No non-mayoral deals have subsequently been concluded, but ministers should make clear that this avenue remains open. Such deals could be a stepping stone to more ambitious mayoral deals in future.

Trailblazer deals are a key test of the government’s boldness on devolution

In addition to the six new deals agreed in 2022, the government has committed to deepen the existing devolution arrangements in Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, through new “trailblazer” deals. Negotiations have yet to conclude, but local leaders are seeking fuller control of transport, skills and employment, housing and net zero delivery, as well as – crucially – funding reform.

A key ask of the two regions is to be treated more like a Whitehall department by the Treasury, replacing the complex system of short-term, ring-fenced grants with a single funding pot. A less ambitious fallback option would be to consolidate the multiple streams of funding into separate pots for core functions such as transport, skills and decarbonisation.

Either model would give local leaders greater flexibility over how to spend money and more long-term certainty. But enhanced devolution will need to be accompanied by accountability reform – for instance through opening metro mayors up to scrutiny by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee and providing greater transparency over performance.

The trailblazer deals are a test of the government’s commitment to radical devolution, and an opportunity to test out new models of governance and funding that can then be emulated elsewhere. To get these deals across the line, the prime minister and chancellor will need to show that they are fully supportive of Michael Gove and the white paper’s vision, and ensure that key departments such as education and transport also stay on side.

The spring statement on 15 March offers an ideal moment to announce the new trailblazer deals and demonstrate progress on the wider devolution agenda – including the promised “spatial reorientation” of policy making in Whitehall – so the next month will be a crucial test of the government’s ability to deliver the rebalancing of power it promised one year ago.

- Topic

- Devolution

- United Kingdom

- England

- Administration

- Sunak government

- English Regions

- West Midlands North East Yorkshire and the Humber East Midlands

- Combined authorities

- West Midlands Combined Authority Greater Manchester Combined Authority

- Public figures

- Michael Gove

- Publisher

- Institute for Government