Performance Tracker 2023: Police

Forces are starting to reverse poor performance, but severe challenges still remain.

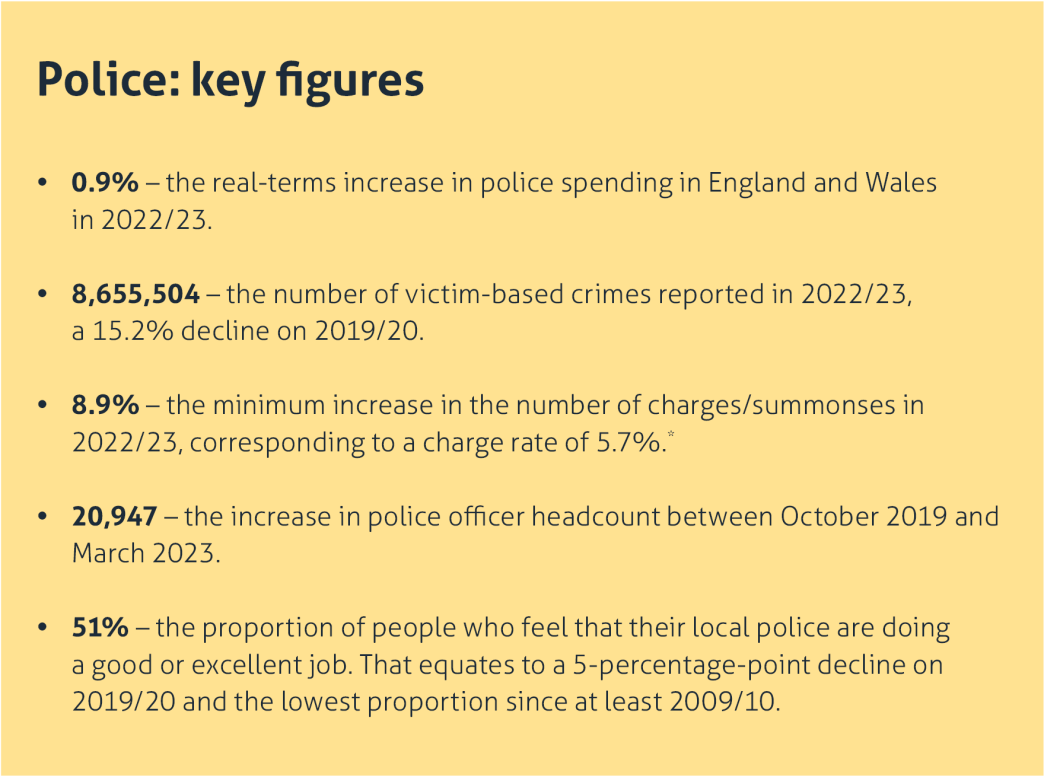

The police service faces an array of challenges. Levels of public trust are at historically low levels – a consequence of a litany of scandals (and repeated failures to address these) and a general and widespread belief that the police cannot adequately deal with crime. While overall levels of reported crime have declined over the last 10 years, so too have charge rates. In the period, police resources have been stretched by the combination of increasing crime complexity and growing non-crime demands.

Police spending has increased significantly in recent years, largely to support the successful recruitment of an additional 20,000 police officers. The decline in the charge rate has been halted, and the absolute number of charges increased in 2022/23 for the first time since 2013/14. Similarly, forces are increasing their focus on sexual assaults, while aiming to reduce the amount of time spent on non-crime demands such as responding to mental health incidents.

However, there is considerable uncertainty about the long-term impact of the additional officers. Forces are under financial strain to maintain officer numbers, while rapid recruitment has led to concerns over the adequacy of vetting arrangements and the burden placed on supervising officers. It will take time to assess whether these changes can lead to a sustained increase in the number of charges, and improvements in public trust.

Police forces have seen big funding increases in recent years

Around 70% of police funding comes from central government. 120 Home Office, ‘Police funding for England and Wales 2015 to 2024: data tables’, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-funding-for-england-and-wales-2015-to-2024 Most of that is passed directly to police and crime commissioners (PCCs), who have broad control over how much is allocated to their force as opposed to other services such as victim support. 121 Brown J, Police and Crime Commissioners, House of Commons Library, October 2021, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06104/SN06104.pdf The rest of the central funding goes to support national efforts like counter- terrorism. 122 Home Office, ‘Police funding for England and Wales 2015 to 2024: data tables’, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-funding-for-england-and-wales-2015-to-2024 The other major funding source is the police precept on council tax. 123 Brown J, Police and Crime Commissioners, House of Commons Library, October 2021, p. 19, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06104/SN06104.pdf This is set by each PCC and since 2015/16 has accounted for between 25% and 30% of annual police funding. 124 Home Office, ‘Police funding for England and Wales 2015 to 2024: data tables’, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-funding-for-england-and-wales-2015-to-2024

Police expenditure declined in real terms by 16.2% between 2009/10 and 2016/17. It has risen significantly in recent years – although remains below 2009/10 levels – with real-terms spending sitting at £17.3bn in 2022/23. One key driver of these recent increases has been the government’s 2019 police uplift programme to increase officer numbers by 20,000, which the National Audit Office (NAO) expected would cost £3.6bn by 2023. In 2022/23, the government provided an additional £550m to PCCs in part to help forces recruit their quota of additional officers, 125 Home Office, ‘Factsheet: Provisional Police Funding Settlement 2022/23’, blog: Home Office in the media, 16 December 2021, https://homeofficemedia.blog.gov.uk/2021/12/16/factsheet-provisional-police-funding-settlement-2022-23 and also allowed them to raise up to £246m through increases to the police precept. 126 House of Commons, Written questions, answers and statements, ‘Police Grant Report (England and Wales) 2022/23’, statement made on 2 February 2022, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2022-02-02/hcws577

Overall crime is at historic lows

Our understanding of crime levels comes from two sources:

-

Police-recorded crime statistics: these statistics come from the crimes reported to – and recorded by – the police. They provide a relatively quick signal of emerging trends, but are influenced by changing recording practices, police activity and public willingness to report crimes. 132 Office for National Statistics, ‘Crime in England and Wales: year ending September 2022’, 26 January 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingseptember2022#strengths-and-limitations

-

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW): conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), this looks at crimes reported by a representative population sample. It measures a smaller number of crimes than police-recorded statistics, but captures crimes not reported to the police and is independent of police recording practices. As such, the CSEW is a better indicator of long-term trends. 133 Office for National Statistics, ‘Crime in England and Wales: year ending September 2022’, 26 January 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingseptember2022#strengths-and-limitations

The CSEW has shown a relatively consistent decline in the number of crimes over the last decade. In 2022/23 this was at its lowest level at 4,384,656 crimes.* This is a 22.5% decline on 2019/20, the most recent year for which comparable data is available. The key contributors to this trend have been declines in theft and violence offences.

Conversely, the levels of police-recorded crime have been increasing in recent years and are now well above levels recorded by the CSEW. Overall police-recorded crime stood at 5,584,888 in 2022/23, some 30.9% above 2009/10 levels and 59.3% above 2013/14 levels.** Contributing to this increase is a growth of 204% in recorded sexual offences between 2013/14 and 2022/23, and a 233% increase in total ‘violence against the person’ offences over the same period.

It is likely that overall crime has declined, while changes in reporting and recording practices largely explain the growth in police-recorded crime.* However, both the police-recorded statistics and CSEW measures agree on the trends for some crimes. For example, aside from a pandemic-led uptick in 2020/21, police-recorded incidents of anti-social behaviour (ASB) have declined consistently every year since at least 2007/08. 134 Office for National Statistics, ‘Crime in England and Wales: other related tables’ (‘Table F21’), 20 July 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/datasets/crimeinenglandandwalesotherrelatedtables The 1,006,197 incidents recorded in 2022/23 stands 25.4% below pre-pandemic levels, and 71.5% below 2009/10 levels.**, 135 Office for National Statistics, ‘Crime in England and Wales: other related tables’ (‘Table F21’), 20 July 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/datasets/crimeinenglandandwalesotherrelatedtables This seems to correspond with the CSEW, which has recorded a relatively consistent decline in perceptions of high levels of anti-social behaviour since 2006/07. 136 Office for National Statistics, ‘Crime in England and Wales: annual supplementary tables’ (‘Table S32’), 20 July 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/datasets/crimeinenglandandwalesannualsupplementarytables

* Excluding fraud and computer misuse.

** Excluding fraud and computer misuse.

Fraud and computer misuse now account for half of all crime

In recent years, digital technology has provided new opportunities for criminals to engage in cyber-crime. According to the CSEW, there were 4.27m fraud and computer misuse offences in 2022/23. The total number of fraud and computer misuse cases has actually fallen by 17.2% since 2016/17, when they were first recorded. However, as a result of a decline in other case types, fraud and computer misuse now account for half of all victim-reported crime (49.3%).

Despite the scale of fraud, the Police Foundation (a policing think tank) has been critical of forces’ response to it. 153 The Police Foundation, A New Mode of Protection: Redesigning policing and public safety for the 21st century, March 2022, www.policingreview.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/srpew_final_report.pdf The absolute number of charges or summonses for fraud has declined by 39% since 2016/17 and in 2022/23 only 0.35% of all reported fraud (which itself is a small proportion of the CSEW figure) resulted in a charge or summons. 154 Home Office, ‘Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2022 to 2023’, 20 July 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/crime-outcomes-in-england-and-wales-2022-to-2023 This partly reflects that a large proportion of fraud incidents either originate abroad or have an international element.

Non-crime demand takes up a significant amount of police time

In addition to responding to crimes, the police also undertake a large amount of non-crime work. This includes demands from mental health, public protection, safeguarding and missing persons activity.

Forces do not measure non-crime demand consistently but it certainly takes up a large amount of police time. For example, in 2015, the vast majority of calls to the police did not result in a crime being recorded (83%),* 155 College of Policing, ‘Estimating demand on the police’, March 2023, https://assets.college.police.uk/s3fs-public/2021-03/demand-on-policing-report.pdf while one study estimated that around 20% of front-line police resource is allocated to incidents requiring mental health engagement. 156 Langton S, Bannister J, Ellison M, Haleem MS and Krzemieniewska-Nandwani K, ‘Policing and mental ill-health: using big data to assess the scale and severity of, and the frontline resources committed to, mental ill-health- related calls-for-service’, Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 2021, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 1963–76, https://academic.oup.com/policing/article/15/3/1963/6332599

There is also some evidence that non-crime demand is growing. For example, 21 of the 48 forces which responded to a recent Freedom of Information (FOI) request reported a rise in mental health incidents since 2017, with one force reporting a 313% rise.

157

Kotecha S and Golding C, ‘Increase in mental health callouts received by police over past five years’, BBC News,

9 March 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-64891572

Cases of detention under the Mental Health Act increased by 36% between 2016/17 and 2021/22.

158

Home Office, 'Police powers and procedures: Other PACE powers, England and Wales, year ending 31 March 2022', 17 November 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-powers-and-procedures-other-pace-powers-england-and-wales-year-ending-31-march-2022

This has been linked to reductions in funding for mental health services.**

159

The Police Foundation, A New Mode of Protection: Redesigning policing and public safety for the 21st century, March 2022, pp. 35-6, www.policingreview.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/srpew_final_report.pdf

Similarly, the number of missing persons incidents, which increased by 65% between 2013/14 and 2019/20, has been estimated to cost the police around 3m investigation hours each year.

160

The Police Foundation, A New Mode of Protection: Redesigning policing and public safety for the 21st century, March 2022, p. 36, www.policingreview.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/srpew_final_report.pdf

Noting that the police often stray into doing the work of other services, the police inspectorate (HMIC) recently argued that “there needs to be greater clarity over what the police’s role in society is”. 161 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, State of Policing: The annual assessment of policing in England and Wales 2022, June 2023, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/state-of-policing-the-annual-assessment-of-policing-in-england-and-wales-2022 The recent ‘Right Care, Right Person’ initiative – which partly seeks to reduce the amount of time police spend on mental health callouts – is one such effort, but its success will take time to evaluate. 162 Department of Health and Social Care and Home Office, ‘National Partnership Agreement: Right Care, Right Person (RCRP)’, policy paper, 26 July 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-partnership-agreement-right-care-right-person/national-partnership-agreement-right-care-right-person-rcrp

* The 83% of calls will, however, include crime-related incidents where no crime was recorded

** For comparability, Avon & Somerset, North Wales, and West Mercia have been excluded.

The number of charges increased sharply in 2022/23 for the first time since 2013/14

Charge rates – that is, the proportion of recorded crimes that resulted in a charge – have declined precipitously over the last decade. This is partly a function of the increase in the number of crimes recorded by the police and in some cases the over-recording of crimes. Recently announced changes to recording practices, which will involve recording fewer crimes (including minor offences committed in the course of a more substantial offence) will likely reduce the number of recorded crimes and increase the charge rate. 163 Home Office, ‘Police given more time to focus on solving crimes and protecting public’, 13 April 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/police-given-more-time-to-focus-on-solving-crimes-and-protecting-public

However, the absolute number of charges issued each year also fell by 43.6% between 2009/10 and 2021/22. This fall likely reflects problems with police performance. Last year, HMIC argued that insufficient supervision, poor digital forensic capability and inadequate capacity had contributed to low charge rates for serious acquisitive crime.

164

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, The Police Response to Burglary, Robbery and Other Acquisitive Crime: Finding time for crime, August 2022, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/police-response-to-burglary-robbery-and-other-acquisitive-crime

HMIC also criticised what it described as the “unacceptably low number of crimes that are solved following investigations”, and identified cases in which investigations were closed before all lines of inquiry had been pursued.

165

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, Police Performance: Getting a grip, July 2023, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/police-performance-getting-a-grip

Indeed, HMIC’s PEEL inspections (which examine the effectiveness of forces) assessed no forces as outstanding when it came to investigating crime.

166

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, Police Performance: Getting a grip, July 2023, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/police-performance-getting-a-grip

The police have come under particular scrutiny for their performance in charging sexual assault and rape. In 2014/15, just 11.3% of sexual assaults and 8.5% of rapes ended up being charged. In 2021/22 this had fallen to 2.9% and 1.3% respectively. The government’s end-to-end rape review highlighted forces’ poor performance against rape investigations. 167 Ministry of Justice, The End-to-End Rape Review Report on Findings and Actions, June 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1001417/end-to-end-rape-review-report-with-correction…;

Similarly, Operation Soteria (a pathfinder programme seeking to identify ways to transform investigations into sexual offences, and now being rolled out to all forces) has found that investigators lack sufficient knowledge about sexual offending, that disproportionate effort was being put into testing the credibility of a victim’s accounts, and that forces lack sufficient data systems to allow for good strategic analysis to improve investigations. 168 Home Office, Operation Soteria Bluestone Year One Report (accessible version), independent report (authored by Professor Betsy Stanko, OBE), 14 April 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/operation-soteria-year-one-report/operation-soteria-bluestone-year-one-report-accessible-version#learnings-from-pr…;

The charge rate rose marginally in 2022/23 to 5.7%, up from 5.5% the year before. The increase in 2022/23 was the result of a minimum 8.9%* increase in the absolute number of charges. This is the first increase in the absolute number of charges since 2013/14. As discussed further below, the increase in the number of charges likely reflects new officers becoming more productive. This was in part driven by a 23.9% (minimum) increase in charges for sexual offences, the largest year-on-year increase since at least 2006/07.

While this likely reflects the efforts inspired by Operation Soteria, the charge rate for sexual offences only increased marginally to 3.6%, significantly below the 2013/14 level. Similarly, overall charges are still at historic lows, and it will take time before forces can demonstrate consistent overall improvements.

* Devon & Cornwall Police did not submit full data in 2022/23.

The government has met its officer recruitment target

In 2019, the government announced the police uplift programme, its plan to increase officer numbers by 20,000 by March 2023. The government has now successfully met this target, increasing officer headcount by 20,947 compared to October 2019. Accounting for attrition, this involved recruiting 46,504 new officers, approximately 31% of the total officer workforce. 170 Home Office, ‘Police officer uplift, final position as at March 2023’, 26 July 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-officer-uplift-final-position-as-at-march-2023

This has contributed to a 14% increase in full-time equivalent (FTE) officer numbers since 2019/20. This is the highest number of officers since at least 2002/03, when comparable records began. 172 Home Office, ‘Police workforce, England and Wales: 31 March 2023’, 26 July 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-workforce-england-and-wales-31-march-2023/police-workforce-england-and-wales-31-march-2023 The recruitment has also accelerated the long-term growth in the proportion of female officers since 2006/07 (women now comprise 35% of all officers compared to 30% in 2018/19 and 23% in 2006/07). It has also had an impact on overall ethnic diversity, with the proportion of non-white officers increasing from 9.3% to 11.0% between 2018/19 and 2022/23.

The police uplift programme may help address key shortages, but also poses several challenges

The roles that new officers are put into will make a big difference to whether the number of charges continues to increase in future years. Interviewees repeatedly stressed concern over the national shortage of detectives. In 2021, there was a shortfall of 6,851 level 2 accredited investigators (dealing with the most complex investigations), a 38% increase on the previous year.

197

The Police Foundation, A New Mode of Protection: Redesigning policing and public safety for the 21st century,

March 2022, p. 104, www.policingreview.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/srpew_final_report.pdf

A lack of suitably qualified detectives can damage both the quantity and the quality of police investigations.

198

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, The Police Response to Burglary, Robbery and Other Acquisitive Crime: Finding time for crime, August 2022, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/police-response-to-burglary-robbery-and-other-acquisitive-crime

Similarly, concerns have been raised about the ability of forces to properly manage and investigate serious acquisitive crime (burglary, robbery and theft), 199 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, The Police Response to Burglary, Robbery and Other Acquisitive Crime: Finding time for crime, August 2022, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/police-response-to-burglary-robbery-and-other-acquisitive-crime and mismatches between the increasing demand for digital forensic examinations and forces’ capacity in this respect. 200 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, An Inspection into How Well the Police and Other Agencies Use Digital Forensics in their Investigations, December 2022, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/how-well-the-police-and-other-agencies-use-digital-forensics-in-their-investigations It appears that the police uplift programme has already contributed to an increase in officers undertaking these roles, with 2,376 additional officers working in investigations in 2022/23 compared to 2018/19. This may explain why the number of charges per officer increased to 2.7 in 2022/23, from 2.6 a year earlier.* This is the first increase since 2013/14, which recorded 4.7 charges per officer. If, as newly deployed officers become fully effective, this figure continues to grow, then this will feed through into a sustained increase in the number of charges as well.

In the short term, new officers are a drain on the productivity of more senior colleagues. Before being able to work independently, new officers require supervision by more experienced ‘tutor constables’. In one survey, the NAO found that these responsibilities may make tutors up to 50% less operationally effective, citing tutor ‘burnout’ as a problem.

201

Comptroller and Auditor General, The Police Uplift Programme, Session 2021-22, HC 1147, National Audit Office,

2022, p. 38, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/The-Police-uplift-programme.pdf

This may have damaged the overall effectiveness of the workforce, as might some of the methods forces have employed to manage this pressure, including giving tutoring responsibilities to less experienced officers and increasing the number of students per tutor.

202

Comptroller and Auditor General, The Police Uplift Programme, Session 2021-22, HC 1147, National Audit Office,

2022, p. 38, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/The-Police-uplift-programme.pdf

The Police Remuneration Review Body has reported that some officers became supervising sergeants after two years of service, leading to concerns that a lack of support would undermine morale and cause retention problems.

203

Police Remuneration Review Body, Ninth Report: England and Wales 2023, (CP 883), July 2023, p. 40, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1170127/PRRB_report_2023_web_accessible_PDF_for_publi…;

There is also evidence that the police uplift programme may have had a negative impact on the composition and thus the performance of police workforces. Officers are supported by other police staff who, as of 2022/23, made up approximately 31% of the total police workforce and include administrators, trainers and investigators. In recent years, these roles have been increasingly occupied by civilian – thus more cost- effective – specialists. 204 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, Observations on the Third Generation of Force Management Statements, March 2022, p. 21, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publications/observations-on-the-third-generation-of-force-management-statements However, the requirement to maintain officer numbers has incentivised forces to replace cheaper staff – who often have specialist skills – with more expensive warranted officers. 205 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Service, State of Policing: The annual assessment of policing in England and Wales 2022, June 2023, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/state-of-policing-the-annual-assessment-of-policing-in-england-and-wales-2022

Despite the overall increase in officer numbers in recent years, the number of police community support officers (PCSOs) declined by 15.6% from 2019/20 to 2022/23. Over this period, many were recruited into the uplift programme. The reduction in PCSOs – whose numbers had already fallen by 45.3% between 2009/10 and 2019/20 – has been cited as a key contributor to the decline in community engagement between forces and citizens. 206 The Police Foundation, A New Mode of Protection: Redesigning policing and public safety for the 21st century, March 2022, p. 35, www.policingreview.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/srpew_final_report.pdf While recent recruitment has boosted the number of neighbourhood officers, this has failed to translate into, for example, greater police visibility, perceptions of which reached their lowest recorded level in 2022/23. 207 Office for National Statistics, ‘Crime in England and Wales: annual supplementary tables’ (‘Table S10’), 20 July 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/datasets/crimeinenglandandwalesannualsupplementarytables This has occurred over a period in which the demands on local policing have intensified, and has contributed to worse outcomes with respect to community engagement, preventative proactivity and visibility. 208 Higgins A, The Future of Neighbourhood Policing, The Police Foundation, May 2018, p. 63, www.police-foundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/TPFJ6112-Neighbourhood-Policing-Report-WEB_2.pdf Indeed, to the extent that the new constables are performing neighbourhood policing roles, this is inefficient, since PCSOs are cheaper to employ than warranted officers.

Finally, concerns have also been raised over the adequacy of the system for vetting police recruits, which has recently led the College of Policing to strengthen its vetting Code of Practice.

209

College of Policing, ‘Vetting Code of Practice updated’, July 2023, www.college.police.uk/article/vetting-code-practice-updated

Concerns that high recruitment demand would place vetting units under substantial pressure were raised at the start of the uplift programme in 2019.

210

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, Shining a Light on Betrayal: Abuse of position for a sexual purpose, September 2022, https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/publication-html/shining-a- light-on-betrayal-abuse-of-position-for-a-sexual-purpose

Despite these warnings, HMIC recently found that vetting units have struggled to cope with their higher caseload.

211

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, An Inspection of Vetting, Misconduct, and Misogyny in the Police Service, pp. 5–10, https://assets-hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/uploads/inspection-of-vetting-misconduct-and-misogyny-in-the-police.pdf

Indeed, HMIC concluded that hundreds of people had likely joined the police in the last few years who should not have.

212

Sky News, ‘Sophy Ridge On Sunday: Grant Shapps, Johnathan Reynolds and Matt Parr’, 5 February 2023, YouTube, 58:58, www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQHDYpeokOM

Similarly, recruiting difficulties and pressure to meet the target have sparked concerns that recruitment practices may have been simplified.

213

Fright M and Richards G, ‘Hitting the 20,000 police officer target won’t fix the criminal justice sector’s problems’, Institute for Government, April 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/police-officer-target

The recruitment of potentially large numbers of unsuitable officers could have a long-term impact on police performance and trust in the police.

* As above, this excludes some data from Devon & Cornwall Police. As such, the number of charges per officer is probably slightly higher

Public trust in the police is falling

The case of David Carrick, who in December 2022 pleaded guilty to 49 offences (including rape) committed over a long career as an officer in the Metropolitan Police, is one of a litany of scandals that have rocked public confidence in the police in recent years. Others – including the murder of Sarah Everard, child strip searches and the Charing Cross scandal – have similarly cast doubt on the police’s ability to appropriately vet and discipline officers (including those with histories of misconduct) and, ultimately, protect the public. This was particularly true of the aftermath of the Carrick case, when it was revealed that over 1,000 allegations of sexual misconduct implicating 800 officers had been spotted by the Met. 214 BBC News, ‘Met chief says 800 officers investigated over sexual and domestic abuse claims’, 16 January 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-beds-bucks-herts-64293158 More recently, the Met has revealed large increases in the number of officers dismissed for gross misconduct, awaiting gross misconduct hearings, or who have been suspended. 215 BBC News, ‘1,000 Met Police officers suspended or on restricted duties’, 19 September 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-66842521

Most of this attention is focused on the Met, which Baroness Casey – in her recent review into behaviour and standards in the Met – labelled institutionally racist, homophobic and sexist.

216

Baroness Casey Review, Final Report: An independent review into the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the Metropolitan Police Service, Baroness Casey of Blackstock DBE CB, March 2023, www.met.police.uk/ SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/met/about-us/baroness-casey-review/update-march-2023/baroness-casey-review-march-2023a.pdf

However, along with the Met, another three forces are also in ‘special measures’,

217

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, ‘Police forces in Engage’, www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/about-us/what-we-do/our-approach-to-monitoring-forces/police-forces-in-engage

an advanced monitoring process for forces not responding to – or unable to deal with – concerns identified by HMIC.

218

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, ‘Our approach to monitoring forces’, www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/about-us/what-we-do/our-approach-to-monitoring-forces

Similarly, there is evidence that claims of sexual misconduct and racism are proportionally higher in several other forces.

These reports have likely contributed to the marked decline in trust in the police among people from minority ethnic backgrounds in particular. One survey from the Mayor’s Office for Police and Crime (covering London) reported that the proportion of Black respondents who believe that the police treat everyone fairly regardless of who they are fell from 64% in 2019/20 to 46% in 2021/22 (having been relatively stable since 2014/15). While such surveys in London consistently display lower rates among Black than White respondents, it is notable that the same survey also displayed a marked – though smaller – decline among White British respondents from 2019/20. 219 Baroness Casey Review, Final Report: An independent review into the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the Metropolitan Police Service, Baroness Casey of Blackstock DBE CB, March 2023, www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/met/about-us/baroness-casey-review/update-march-2023/baroness-casey-review-march-2023a.pdf

Trust in the police among the general population is also declining. The share of CSEW respondents reporting that their local police are doing a good or excellent job fell by 5 percentage points between 2019/20 and 2022/23, to 51%. This is down from 63% in 2015/16. Interestingly, the ethnic groups with the largest proportion claiming the police are doing a good or excellent job are Asian, Black and Other ethnic groups. Respectively, 59%, 56% and 63% of the respondents in these groups believed their local police were doing a good or excellent job in 2022/23, compared to 50% of White respondents.

220

Office for National Statistics, ‘Crime in England and Wales: annual supplementary tables’ (‘Table S2’), 20 July 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/datasets/crimeinenglandandwalesannualsupplementarytables

Overall, data from YouGov indicates a marked loss of confidence in recent years. Averaging figures over a 12-month period in a survey carried out between October 2022 and September 2023, more than half of respondents said they had either not very much or no confidence at all in the police to deal with crime (52%), compared to 48% in the previous 12-month period. 223 YouGov, ‘How much confidence Brits have in police to deal with crime’, (no date), https://yougov.co.uk/topics/ legal/trackers/how-much-confidence-brits-have-in-police-to-deal-with-crime Similarly, in a different survey, averaged figures over the same period showed that half of respondents felt the police were doing a good job compared to 60% a year earlier. 224 YouGov, ‘Are the police doing a good job?’, (no date), https://yougov.co.uk/topics/legal/trackers/are-the-police-doing-a-good-job

- Topic

- Public services

- Department

- Ministry of Justice

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government