Police accountability

Several recent high-profile scandals have brought into focus the need for strengthened police accountability.

Why is police accountability important?

British policing is based on consent, meaning the ability of the police to carry out their functions rests on ‘public approval of their existence, actions and behaviour’.[1] Accountability is therefore essential to ensure the police’s responsiveness to the public.

However, several recent high-profile scandals have strained this relationship and brought into focus the need for strengthened accountability.

How are police forces structured?

There are 43 territorial forces covering England and Wales, some of which hold national responsibilities. For example the Metropolitan Police (the Met) responsible for most of London is also responsible for counter-terrorism.[2]

Above the territorial forces are 10 regional organised crime units that perform specialist functions.[3] Other forces also perform national functions, such as the British Transport Police, which serves the railway network.

How do police and crime commissioners hold police forces to account?

Democratic accountability is exercised through elected police and crime commissioners (PCCs). In some areas, the mayor fulfils this role.

The responsibilities of PCCs include appointing their forces' chief constable, setting its budget and strategic objectives, and for scrutinising performance. The Met’s chief – known as the met commissioner – is appointed by the home secretary.

PCCs scrutinise their forces by, for example, publishing reports and data on their forces’ performance, and scrutinising their forces’ handling of complaints. Between elections, PCCs are scrutinised by police and crime panels (PCPs). These can require PCCs to answer questions, make recommendations on the PCCs plans, and veto the appointment of chief constables.[4]

Chief constables are responsible for operational delivery, setting standards and conducting national operations.[5] While PCCs usually appoint, scrutinise, and can dismiss chiefs, this relationship is tempered by the chief’s operational independence, meaning forces will always remain under the operational control of its chief.[6]

What other organisations play a role in police accountability?

The home secretary is responsible for setting out the capabilities required to manage national threats (published in a Strategic Policing Requirement), for providing grants to PCCs, and overseeing bodies like the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC). The home secretary can also direct poorly performing forces to develop plans to address their failings.[7]

His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFS, whose head is appointed by the home secretary) inspects and reports on the effectiveness of forces, making recommendations to improve their service.[8]

The IOPC investigates serious complaints against the police, including cases of ‘deaths following police contact’.[9] It also monitors the complaints system and recommends improvements arising from misconduct issues.[10]

How do complaints against the police work?

The complaints system is important for holding officers to account. By ensuring malpractice is addressed, the system seeks to increase the legitimacy of, and so public confidence in, the police. This process has two parts: complaints and discipline.

The complaints process has four stages: first, a complaint must be recorded if it meets certain conditions (for example, if the complaint alleges criminality). Second, forces must decide whether to refer a complaint to the IOPC (while most complaints are dealt with by a forces’ own professional standards department, certain serious complaints must be referred).[11] Third, a decision on whether or how to investigate a case is made. Finally, complainants can request their case be reviewed, by the IOPC or relevant PCC.

Disciplinary processes are used when an officer is found to have engaged in behaviour that would ‘damage public confidence in policing’.[12] Sanctions include written warnings, demotions and dismissals.[13]

What are recent criticisms of the police complaints process?

Complaints and conduct

The complaints process can be slow. A recent review into the Met found that it takes an average of 400 days to make decisions on misconduct allegations.

Few complaints result in dismissals. Since 2013 only 0.7% of officers facing repeated allegations of misconduct were dismissed.[14] This is particularly concerning given reports of possible failures to investigate prior allegations against Sarah Everard’s killer while a serving police officer.[15]

Most complaints are investigated by forces themselves. This can leave senior officers free to overrule misconduct investigators - professional standards departments are seen as insufficiently transparent.[16]

However, the introduction of ‘legally qualified persons’ to oversee misconduct hearings reduced each forces’ control over their outcome. In the Met, this has coincided with fewer dismissals of officers facing gross misconduct allegations.[17] It has been argued that misconduct matters should be decided by senior officers with concern for their forces’ reputation. Some chiefs have taken their forces’ misconduct panel to court when their decision has been too lenient.[18] Similarly, the threshold for determining behaviour that warrants gross misconduct has been criticised for being too high (becoming almost synonymous with criminality).[19]

Wider issues

There are also concerns over the wider systems of accountability to which forces answer. A clear case is the Met, whose former commissioner Cressida Dick resigned in February 2022 after the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, lost confidence in her leadership. However, the then home secretary, Priti Patel, disagreed with this and commissioned a review into the resignation, which criticised the mayor’s actions.[20]

Recent research also highlights the lack of formal sanctioning powers as a key contributor to the impotency of PCPs. Consequently, PCCs are effectively free of scrutiny between elections, while the success of local accountability is left dependent on the contingent ‘one-to-one’ relationship between PCCs and chiefs.[21]

Are there any proposals to reform police accountability?

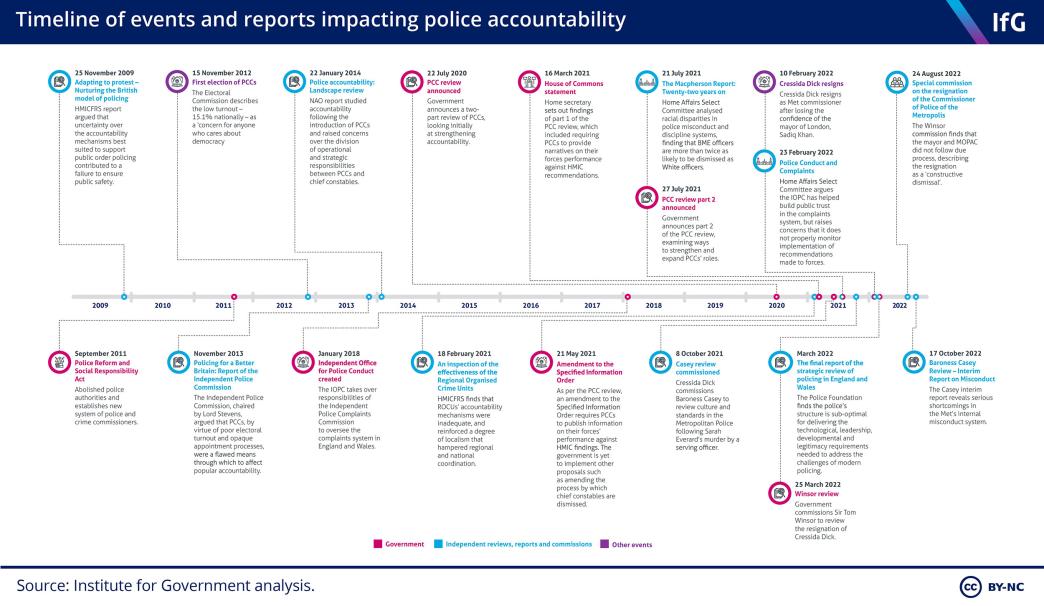

In July 2020 then policing minister Kit Malthouse announced a review to evaluate ways to strengthen PCCs’ accountability.[22] Among the changes introduced following the first part of the review is the requirement that PCCs report on their forces’ performance against HMICFRS’ recommendations. Other changes have yet to be implemented, including amendments to the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 to clarify the dismissals process between PCCs and chiefs.[23]

The new Met commissioner, Mark Rowley, recently indicated his desire to make it easier to dismiss poorly performing officers, who are often protected by appeals tribunals.[24] This comes after a parliamentary inquiry reported that, despite its success in cutting investigation times, the IOPC still needs to speed up complaints investigations (including by increasing scrutiny of those who delay investigations). It also urged government to undertake bi-annual reviews of forces’ progress against IOPC recommendations.[25]

- Definition of policing by consent - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- CBP-8582.pdf (parliament.uk) p.18

- Regional Organised Crime Units (ROCUs) - NCSC.GOV.UK

- www.gov.uk/government/publications/police-and-crime-panels/police-fire-and-crime-panels-guidance

- Policing in the UK: Governance, Oversight and Complaints (parliament.uk) p.8

- Operational Independence and the New Accountability of Policing (justiceinspectorates.gov.uk) p.4

- CBP-8582.pdf (parliament.uk) p.13

- www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/about-us/what-we-do/

- Who we are | Independent Office for Police Conduct

- CBP-8582.pdf (parliament.uk) pp.15-16

- Police conduct and complaints (parliament.uk) p.19

- Home_Office_Statutory_Guidance_0502.pdf (publishing.service.gov.uk) p.31

- Ibid, pp.139-140

- www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/met/about-us/baroness-casey-review/baroness-casey-review-interim-report-on-misconduct.pdf pp.3-9

- www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/publication-html/an-inspection-of-vetting-misconduct-and-misogyny-in-the-police-service/#summary

- Police conduct and complaints (parliament.uk) p.26

- www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/met/about-us/baroness-casey-review/baroness-casey-review-interim-report-on-misconduct.pdf pp.6-14

- www.ukpolicelawblog.com/misconduct-panel-s-decision-to-impose-a-final-written-warning-for-racist-remarks-quashed-by-the-high-court/

- www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/met/about-us/baroness-casey-review/baroness-casey-review-interim-report-on-misconduct.pdf pp.6-14

- www.gov.uk/government/publications/commissioner-accountability-review/special-commission-on-the-resignation-of-the-commissioner-of-police-of-the-metr…

- Police Relational Accountabilities: The Paralysis of Police Accountability? - Research Repository (essex.ac.uk)

- https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2020-07-22/debates/20072232000015/PoliceAndCrimeCommissionerModelReview

- Written statements - Written questions, answers and statements - UK Parliament

- www.thetimes.co.uk/article/my-officers-will-go-to-every-burglary-and-wont-be-taking-the-knee-says-new-met-chief-sir-mark-rowley-kk8q0r0r5 p.5

- Police conduct and complaints (parliament.uk) pp.49-50

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Criminal justice Accountability

- Department

- Ministry of Justice

- Publisher

- Institute for Government