Performance Tracker 2023: Schools

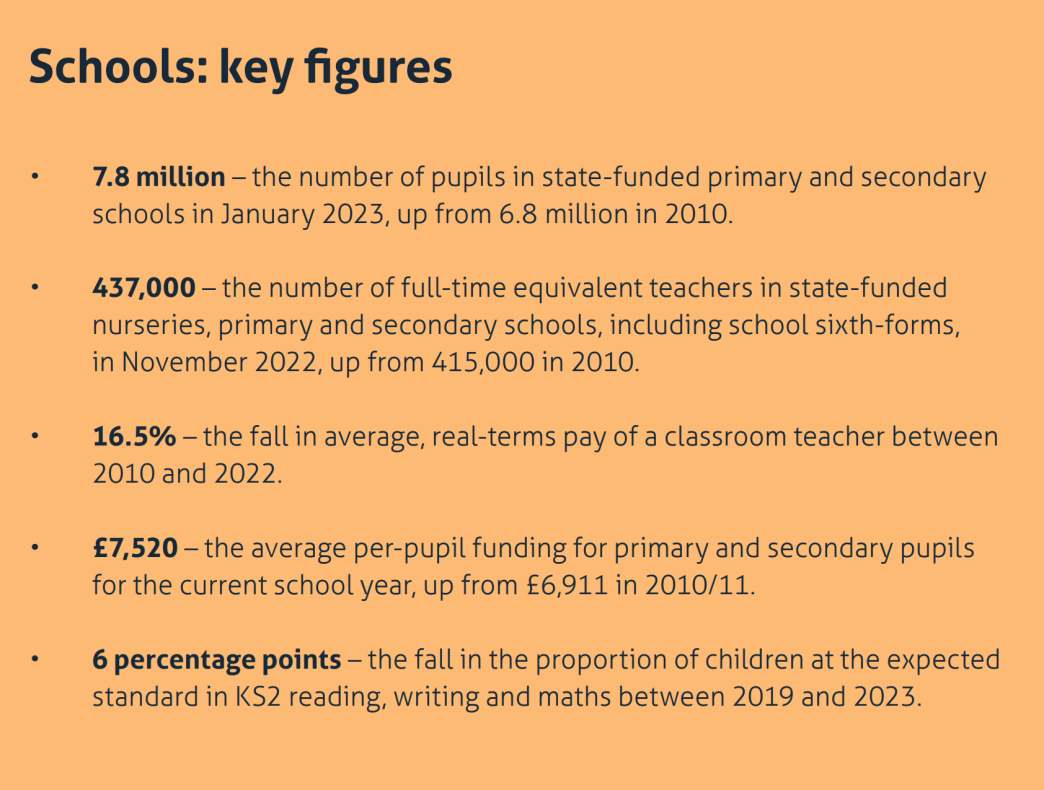

A recruitment crisis, problems with pupil attendance and the presence of RAAC are all presenting challenges for schools.

The start of the 2023–24 academic year was marked by a schools crisis. Some 104 schools and colleges were told by the Department for Education (DfE) at very short notice that they would not be able to reopen in part or in whole due to the risk posed by concrete used in their construction.

This followed disruption in the latter half of the previous school year, as members of the National Education Union went on strike for an accumulated eight days in a long- running dispute over pay. And while the government has provided additional money to fund the pay award that was eventually agreed, some schools will still find their finances are very tight.

Meanwhile, the attainment of primary school pupils is considerably down on pre- pandemic levels and pupil absence rates have grown alarmingly.*

* This chapter focuses on mainstream, state-funded schools in England serving pupils aged 5–16. It covers both local authority maintained schools and academies but, unless otherwise stated, excludes special schools, alternative provision, early-years and post-16 education.

Pupil numbers have peaked

Demographic trends – namely a baby boom that ended in 2013 – mean pupil numbers have been declining for several years in primary schools and are forecast to peak in secondary schools in 2024.

The changes are not uniform across the country: primary pupil numbers have decreased by 5.1% in London since 2019, when numbers peaked nationally, while other areas have seen either more modest decreases or small increases. 179 Department for Education, ‘Schools, pupils and their characteristics: Academic year 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 13 June 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics/2022-23 Think tank and media reports have attributed this to a growing number of young people being unable to afford starting a family in the capital. 180 Burn-Murdoch J, ‘London’s parasitical housing market is driving away young families’, Financial Times, 21 April 2023, retrieved 27 June 2023, www.ft.com/content/d6bc22ed-d6d8-464b-b706-b4d478c6baf1 , 181 Tabbush J, ‘Is inner London becoming a ‘child-free area’?’, Centre for London, 7 November 2022, retrieved 27 June 2023, https://centreforlondon.org/blog/london-child-free

Alongside demographic changes there appears to have been a growth in home education since the start of the pandemic. Department for Education figures (published for the first time) estimated there were 116,300 children in elective home education at any point during the 2021–22* academic year.

182

Department for Education, ‘Elective home education: Academic year 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 18 May 2023,

https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/elective-home-education

An estimate from the Association of Directors of Children’s Services put the number of home-schooled children at around 79,000 in 2018–19.

183

Association of Directors of Children’s Services, ‘Elective Home Education Survey 2019’, Association of Directors of Children’s Services, November 2019, https://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ADCS_Elective_Home_Education_Survey_Analysis_FINAL.pdf

* This chapter refers to both academic school years and financial years. We refer to school years as 20XX–YY, and financial years as 20XX/YY.

Per-pupil funding has increased from recent lows

Core schools funding increased from £46.7bn in 2010/11 to £54.9bn in 2022/23 (both in 2023/24 terms), equating to a real-terms increase of 17.5%. Most school revenue funding is provided on a per-pupil basis, however, so some of this increase purely reflects the fact that overall pupil numbers are higher now than in 2010. Per-pupil funding fell in real terms between 2014/15 and 2017/18 – but by 2022/23 stood at £7,156 per pupil, the highest level to date, and 3.5% above 2010/11 levels.*,**,

184

Department for Education, ‘School funding statistics: Financial year 2022-23’, GOV.UK, January 2023,

https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-funding-statistics/2022-23

While per-pupil funding has increased on average, the experience of individual schools varies. The government brought in a national funding formula in 2018/19 to address discrepancies in the funding that similar schools in different parts of the country received – but subsequent changes have been brought in to more generally ‘level up’, or equalise, funding nationally. 196 Department for Education, ‘Fairer school funding plan revealed’, press release, 7 March 2016, www.gov.uk/government/news/fairer-school-funding-plan-revealed , 197 Johnson B, ‘Conservatives must address our country’s shocking educational disparities’, The Telegraph, 2 June 2019, retrieved 10 August 2023, www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2019/06/02/conservatives-must-address-countrys-shocking-educational-disparities

Schools serving more deprived communities still get more funding per pupil than those in less deprived ones. But analysis by the National Audit Office (NAO) found that between 2017/18 and 2020/21 most London boroughs saw real-terms decreases in per-pupil funding, as did other areas with relatively high levels of deprivation such as Nottingham and Birmingham. Conversely, local authorities with lower levels of deprivation in the South West, the East Midlands and the South East received real-terms increases. 198 Comptroller and Auditor General, School Funding in England, Session 2021-22, HC 300, National Audit Office, 2 July 2021.

Analysis of changes up to 2021/22 by the Education Policy Institute, meanwhile, concluded that “the link between funding and pupil need is being weakened”, on average benefiting schools in more affluent areas. 199 Andrews J, ‘Analysis: School funding allocations 2021-22’, Education Policy Institute, 7 August 2020, retrieved 10 August 2023, https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/school-funding-allocations-2021-22

* Figures have been put into 2023/24 terms using a smoothed version of the Office for Budget Responsibility’s GDP deflator. See Methodology for further details. These figures cover both mainstream and non-mainstream schools, and cover major revenue funding streams but exclude some smaller elements of revenue funding and specific Covid-19 funding.

** Including school sixth-forms, where there were greater funding cuts in the years after 2010 than in 5–16 education, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has calculated that spending per pupil will only return to 2010/11 levels in 2023/24 – and if a schools-specific measure of inflation is used, funding will not in fact have returned to that level by the end of the current spending review period, 2024/25. See Sibieta L, ‘What is happening to school funding and costs in England?’, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 5 October 2023, retrieved 10 October 2023, https://ifs.org.uk/articles/what-happening-school-funding-and-costs-england

Far more pupils have special education needs and disabilities, increasing spending on this

As well as growth in overall pupil numbers since 2010, there has been a huge increase in the number of pupils with education, health and care plans (EHCPs). These are issued where a child requires a higher level of special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) support, and set out in detail the support required. The number of EHCPs has increased from 232,000 (2.8% of all pupils) in 2014 to 389,000 (4.3%) in 2023.* Around half of pupils with EHCPs are in state-funded mainstream primary and secondary schools. (Most other pupils with EHCPs attend state-funded special schools, but a sizeable minority attend independent special schools.) 200 Department for Education, ‘Special educational needs in England: Academic Year 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 22 June 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/special-educational-needs-in-england/2022-23

Growth in the number of pupils requiring this higher level of support has been at least partly driven by what the government has described as a vicious cycle: a lack of inclusivity in mainstream schools coupled with late intervention leading to escalating needs, prompting families or schools to seek EHCPs, which in turn means more resources are diverted from mainstream provision, prompting more late intervention. 201 Department for Education, SEND Review: Right support, right place, right time, CP 642, pp. 23–24, The Stationery Office, March 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1063620/SEND_review_right_support_right_place_right_t… Other factors include more common diagnoses of developmental disabilities such as autism. 202 Van Herwegen J, ‘Why the rise in number of SEN children, especially in the early years?’, University College London, 4 April 2022, retrieved 20 June 2023, https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/cdld/2022/04/04/why-the-rise-in-number-of-sen-children-especially-in-the-early-years

For pupils with SEND in mainstream schools, the first £6,000 of spending on additional support must be funded from schools’ general funding allocations, but separate ‘high needs’ funding exists to cover support above this level. High needs funding from the DfE pays for places in special schools and spending on alternative provision – and funds learning support for young people with SEND outside of school ages (up to age 25).

High needs funding is expected to total £10.1bn in 2023/24, an increase of 35.9% in real terms since 2019/20. This is much greater than the rise in core schools funding, which over the same period has increased by 11.4% in real terms.**, 203 Figures provided directly by the Department for Education Despite the enormous increase in high needs funding, in 2021/22, three quarters of local authorities were in deficit on the part of their education budgets reserved for schools spending due to the cost of meeting their statutory SEND duties. As of March 2022, the combined deficit totalled £1.4bn, up from £1.0bn a year earlier (discussed further in the ‘Cross-service analysis’ chapter). 204 Department for Education, ‘LA and school expenditure: Financial Year 2021-22’, GOV.UK, 8 December 2022, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/la-and-school-expenditure/2021-22

* The SEND system was reformed in 2014. The SEND system now covers young people up to the age of 25, but these figures relate specifically to school pupils. Figures in the first years after the reforms include SEN statements, which were replaced by EHCPs.

** Some of this includes high need funding. However, it is not possible to determine how much as no breakdown is available.

There are record numbers of teachers but the government is missing initial teacher training targets by a huge margin

Both teacher and teaching assistant numbers reached a record high in 2022. 205 Department for Education, ‘Schools’ costs: 2022 to 2024’, GOV.UK, February 2022, p. 3, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1137908/Schools__costs_2022_to_2024.pdf , 206 Department for Education, ‘School workforce in England: Reporting Year 2022’, GOV.UK, 15 June 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-england/2022 In the case of teacher numbers, this was driven by growing numbers of teachers in secondary schools, masking a slight decline in primary teacher numbers. (In this section, figures for primary schools includes those working at nursery level and figures for secondary schools includes those working in school sixth-forms.)

With pupil numbers peaking, these numbers mean pupil–teacher ratios have been broadly stable in primary schools since at least 2010. The ratios had deteriorated considerably for secondary schools between 2013 and 2019, but have been broadly stable since then. 208 Department for Education, ‘School workforce in England: Reporting Year 2022’, GOV.UK, 15 June 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-england/2022

Recruitment to initial teacher training courses is at crisis levels, however. The government sets annual targets covering postgraduate training, which accounts for the bulk of teacher training. These targets are intended to make sure that the schools system has sufficient numbers of teachers in future, based on trends in pupil numbers and assumptions about teacher leaver rates. The numbers entering postgraduate training have dropped starkly since the pandemic, coming in at only 23,000 in 2022– 23, around 30% below target. And the picture is particularly bad in some secondary school subjects – a target for physics, the worst performer, was missed by 83%. 211 Department for Education, ‘Initial Teacher Training Census: Academic Year 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 1 December 2022, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/initial-teacher-training-census/2022-23

In recognition of the recruitment crisis, in October 2023 the government doubled the size of grants for new teachers of some shortage subjects working in certain deprived parts of the country, to £6,000 annually for five years. 212 Department for Education, ‘£196 million to support new trainee teachers’, press release, 10 October 2023, retrieved 10 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/196-million-to-support-new-trainee-teachers

The share of teachers leaving the state-funded school system fell with the onset of the pandemic but has subsequently returned to pre-pandemic levels – and the out-of- service leaver rate, covering those who quit for other work or education (as opposed to retiring or dying) reached its highest level since at least 2010–11 in 2021–22.

215

Department for Education, ‘School workforce in England: Reporting Year 2022’, GOV.UK, 15 June 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-england/2022

Institute for Government research on public sector retention published in October 2023 identified disgruntlement over workloads and a lack of flexible working as well as unhappiness over pay as factors behind increasing exit rates.

216

Davies N, Fright M and Richards G, Retention in public services, Institute for Government, 9 October 2023,

www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/staff-retention-public-services

Staff pay is schools’ biggest cost and has increased by less than inflation

Staff costs account for around 80% of school spending. 220 Department for Education, ‘Schools’ costs: 2022 to 2024’, GOV.UK, February 2022, p. 3, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1137908/Schools__costs_2022_to_2024.pdf In 2011–12 and 2012–13 there were pay freezes for those working in schools, in common with other areas of the public sector, with below-inflation pay awards between 2013–14 and 2017–18. This, coupled with high inflation since 2021, means median pay fell by 16.5% in real terms between 2010 and 2022 for classroom teachers, by 15.0% for those in leadership roles excluding headteachers, and by 10.8% for headteachers. 221 Department for Education, ‘School workforce in England: Reporting Year 2022’, GOV.UK, 15 June 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-england/2022 , 222 Office for National Statistics, ‘Consumer price inflation, UK: May 2023’, 21 June 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/consumerpriceinflation/may2023

Disgruntlement with 2022–23 pay awards led to members of the National Education Union (NEU) going on strike for eight days between February and July 2023. 234 Standley N, ‘Teacher strikes in England end as all four unions accept pay deal’, BBC, 31 July 2023, retrieved 11 August 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-66360677 The strikes ended after the NEU and other teaching unions accepted a pay deal in July that gives teachers a 6.5% pay rise for 2023–24 – though one union, NASUWT, is continuing with action short of a strike over teacher working hours and workload. 235 Prime Minister’s Office and Department for Education, ‘Joint Statement on Teachers’ Pay: 13 July 2023’, press release, 13 July 2023, retrieved 11 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/joint-statement-on-teachers-pay-13-july-2023 , 236 NASUWT, ‘New industrial action campaign at schools and colleges in England’, 18 September 2023, retrieved 28 September 2023, www.nasuwt.org.uk/article-listing/new-industrial-action-schools-and-colleges-england.html

Given the crisis in initial teacher training recruitment, the National Foundation for Educational Research has said that the 6.5% pay award is welcome. 237 National Foundation for Educational Research, ‘NFER comment on government pay announcement‘, press release, 13 July 2023, www.nfer.ac.uk/press-releases/nfer-comment-on-government-pay-announcement/ It has, however, warned that pay will need to increase by more than average earnings in the economy as a whole in future years if there is to be a significant improvement in teacher recruitment and retention. 238 Tang S and Worth J, ‘Policy options for a long-term teacher pay and financial incentives strategy’, National Foundation for Educational Research, 12 July 2023, https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/ojeez5in/policy_options_for_a_long_term_teacher_pay_and_financial_incentives_strategy.pdf

Besides teacher salaries, pay deals covering many school support staff increased pay by up to 10.5% for the lowest paid staff in 2022/23,* while a proposed award for 2023/24 would raise pay by up to 9.4%. (In both years, pay offers are for a fixed amount of £1,925 – which translates into a large increase in percentage terms for generally low-paid support staff.) 239 Kenyon M, ‘Council staff offered £1,925 pay rise’, Local Government Chronicle, 23 February 2023, www.lgcplus.com/politics/workforce/council-staff-offered-1925-pay-rise-23-02-2023

* These pay awards cover financial years, unlike the pay awards covering teachers.

School financial health improved on average during the pandemic

School income and expenditure were both affected by the pandemic. The Department for Education provided schools with some specific Covid-19 revenue funding, while schools’ self-generated income – such as from letting out meeting spaces and sports halls – fell. Schools spent more on teaching and support staff, but expenditure on exam fees, development and training, and indirect employee expenses all decreased. 240 Department for Education, ‘School finances during the Covid-19 pandemic: Financial year 2021-22’, GOV.UK, 17 July 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-finances-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

Overall, school income increased by more than expenditure for the typical school in 2020/21* – and DfE has concluded that this would have been true even without Covid- specific grant funding, because of increases in general revenue funding. 241 Department for Education, ‘School finances during the Covid-19 pandemic: Financial year 2021-22’, GOV.UK, 17 July 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-finances-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

The share of schools and academy trusts with cumulative negative reserves** can be used as a proxy for the financial health of the system. For local authority maintained schools, where data is more available than for academies, the picture has been far more variable for secondary schools than for primary schools since 2009/10.

The percentage of maintained secondary schools with cumulative negative reserves increased from 11.2% in 2013/14 to a high of 30.2% in 2017/18, during which time per-pupil funding was stagnant or falling in real terms and secondary school pupil numbers were increasing. The share of schools in this position has fallen sharply since then, reaching 12.9% in 2021/22, due to per-pupil funding increasing in real terms, and income going up by more than expenditure on average during the pandemic. For local authority maintained primary schools, the proportion of schools in poor financial health has stuck within a smaller range, ending 2021/22 at a level similar to that seen in 2009/10. 242 Department for Education, ‘LA and school expenditure: Financial Year 2019-20’, GOV.UK, 21 January 2021, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/la-and-school-expenditure/2019-20 , 243 Department for Education, ‘LA and school expenditure: Financial Year 2020-21’, GOV.UK, 16 December 2021, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/la-and-school-expenditure/2020-21 , 244 Department for Education, ‘LA and school expenditure: Financial Year 2021-22’, GOV.UK, 8 December 2022, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/la-and-school-expenditure/2021-22

For academy trusts, including those covering non-mainstream schools, the proportion with cumulative negative reserves decreased from 4.1% to 2.6% between 2019–20 and 2020–21, the first full school year of the pandemic. 259 Department for Education, ‘Academy trust revenue reserves 2019 to 2020’, GOV.UK, 1 July 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/academy-trust-revenue-reserves-2019-to-2020 , 260 Department for Education, ‘Academy trust revenue reserves 2020 to 2021’, GOV.UK, 19 April 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/academy-trust-revenue-reserves-2020-to-2021 More recent figures have not been published for academies.

Funding increases for 2023/24 exceed expected cost increases

Looking ahead, per-pupil funding is increasing from £7,156 in 2022/23 to £7,520 in 2023/24 (both in 2023/24 terms), equating to a 5.1% increase. 261 Department for Education, ‘School funding statistics: Financial year 2022-23’, GOV.UK, January 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-funding-statistics/2022-23 , 262 Figures provided directly by the Department for Education. This comes after the government increased schools funding at the 2022 autumn statement, and separately provided £432.5m of funding for 2023/24 towards the cost of the September 2023 teacher pay award. (The government will provide a further £742.5m to cover the cost of the pay award for 2024/25.)*, 263 Figures provided directly by the Department for Education.

The Department for Education describes the 6.5% teacher pay award as “properly funded” – that is, nationally, increases in funding cover expected cost increases for schools, helped by energy bills coming in lower than expected, plus this additional funding from the department. 264 Prime Minister’s Office and Department for Education, ‘Joint Statement on Teachers’ Pay: 13 July 2023’, press release, 13 July 2023, retrieved 11 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/joint-statement-on-teachers-pay-13-july-2023 On its calculations, the funding provided in the 2022 autumn statement means schools could on average afford a 4% pay award, while the additional grant funding is sufficient for a 3% teacher pay award. Taking these figures together, the department says that the additional funding being made available in 2023/24 is more than is strictly needed to cover the 6.5% pay award. 265 Department for Education, ‘Teacher strikes: Everything you need to know about the 2023/24 teacher pay award’, GOV.UK, 13 July 2023, retrieved 16 August 2023, https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2023/07/13/teacher-strikes-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-2023-24-teacher-pay-award

This ignores the distributional effect, however – some schools will be more affected than others. The department does not model the effect on individual schools, though schools in London – which have received lower than average per-pupil funding increases in 2023/24 266 Department for Education, ‘2023 to 2024 schools and high needs additional allocations’, GOV.UK, 16 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/dedicated-schools-grant-dsg-2023-to-2024 – and schools with high SEND rates employing more support staff are more likely to feel financial pressure than some of their peers.

The Department for Education has said that the additional funding for the pay award will come from its existing budget, but has said that core school and college budgets will not be cut. 267 Department for Education, ‘Teacher strikes: Everything you need to know about the 2023/24 teacher pay award’, GOV.UK, 13 July 2023, retrieved 16 August 2023, https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2023/07/13/teacher-strikes-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-2023-24-teacher-pay-award In part, funding will come from an underspend on the National Tutoring Programme, which DfE has gained permission to retain rather than pass back to the Treasury. 268 Whittaker F, ‘£2bn school funding boost ‘didn’t go far enough’, admits Keegan’, Schools Week, 17 July 2023, retrieved 16 August 2023, https://schoolsweek.co.uk/2bn-school-funding-boost-didnt-go-far-enough-admits-keegan Beyond 2023/24 and 2024/25, the ongoing cost of the teacher pay award is likely to require further money from the Treasury.

In the medium term, the government’s success in implementing its SEND and alternative provision improvement plan, published in March 2023, will also have a material effect on spending on both mainstream and special schools. This plan aims to improve experiences of the SEND system, standardise provision nationally and make mainstream education more inclusive. 269 Department for Education, Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) and Alternative Provision (AP) Improvement Plan, CP 800, March 2023, p. 6, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1139561/SEND_and_alternative_provision_improvement_pl… The plan’s broad principles have support from the sector, and, if implemented successfully, could act as a brake on soaring high needs spending by reducing the use of independent provision. 270 National Association for Special Educational Needs, ‘Nasen responds to the publication of The SEND and Alternative Provision Improvement Plan’, press release, 2 March 2023, https://nasen.org.uk/news/nasen-responds-publication-send-and-alternative-provision-improvement-plan , 271 Education Policy Institute, ‘EPI comments on DfE’s release of the SEND and AP Improvement Plan’, press release, 2 March 2023, https://epi.org.uk/comments/epi-comments-on-dfes-release-of-the-send-and-ap-improvement-plan , 272 Association of School and College Leaders, ‘ASCL comment ahead of publication of SEND and AP Improvement Plan’, press release, 2 March 2023, www.ascl.org.uk/News/Our-news-and-press-releases/ASCL-comment-ahead-of-publication-of-SEND-and-AP-I

Changes are likely to meet opposition from parents, however, who would face a restriction of school choice for their child. This, together with a lack of detail on the level around which provision will be standardised – in line with the best support available now, or at a lower level – make it hard to quantify the future impact.

* These figures relate strictly to mainstream primary and secondary schools. Figures of £482.5m and £827.5m reported elsewhere include £50m and £85m of post-16 funding for 2023/24 and 2024/25 respectively.

The school estate

Just days before the start of the current academic year, 104 schools and colleges were ordered not to reopen in part or in whole by DfE due to the risk of collapse posed by concrete used in their construction. 279 Department for Education, ‘New guidance for schools impacted by RAAC’, GOV.UK, 31 August 2023, retrieved 1 September 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/new-guidance-for-schools-impacted-by-raac Further investigations took the total number of institutions with confirmed cases of reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) in their buildings to 214 by 16 October 2023, the latest date for which figures are available. 280 Department for Education, ‘Updated List of Education Settings with RAAC’, GOV.UK, 19 September 2023, retrieved 26 September 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/updated-list-of-education-settings-with-raac

The department has considered the risk of a school building collapse to be ‘very likely’ since July 2021 and is prioritising affected schools in a rebuilding programme, though the head of the NAO has said that the risks posed by RAAC took too long to be addressed. 281 Department for Education, Consolidated Annual Report and Accounts: For the year ended 31 March 2022 (HC 918), p106, The Stationery Office, 19 December 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1125417/DfE_consolidated_annual_report_and_accounts_2… , 282 Davies G, ‘It’s not just concrete, the government’s IT is cracking up too’, The Times, 5 September 2023, www.thetimes.co.uk/article/it-s-not-just-concrete-the-government-s-it-is-cracking-up-too-7kbrs5q8r

This comes after capital spending by DfE – the vast majority of which goes on schools – decreased markedly after the government cancelled the Building Schools for the Future programme in 2010. 283 Curtis P, ‘School building programme scrapped in latest round of cuts’, The Guardian, 5 July 2010, retrieved 11 August 2023, www.theguardian.com/education/2010/jul/05/school-building-programme-budget-cuts Even before the latest problems with RAAC emerged, the NAO reported in June 2023 that “in recent years, funding for school buildings has not matched the amount DfE estimates it needs, contributing to the estate’s deterioration”. 284 Comptroller and Auditor General, Condition of school buildings, HC 1516, National Audit Office, 28 June 2023, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/condition-of-school-buildings.pdf

The last survey of the school estate, carried out between 2017 and 2019 and published in May 2021, estimated the cost of returning all elements of the primary and secondary school estate to a good condition at £10.6bn.* There was considerable variation in the condition need by region, with schools in the East Midlands, for instance, requiring around twice as much investment per square metre as those in the South West. 288 Department for Education, Condition of School Buildings Survey: Key findings, Department for Education, May 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/989912/Condition_of_School_Buildings_Survey_CDC1_-_ke…

Planned DfE capital spending of £7.0bn for 2023/24 is higher in real terms than capital budgets have been at any point since 2016/17, though is 13.1% below the level seen in 2007/08, and even further below the unusually high amounts seen in 2009/10 and 2010/11. 289 HM Treasury, Spring Budget 2023, HC 1183, The Stationery Office, March 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1144441/Web_accessible_Budget_2023.pdf With total pupil numbers peaking, capital spending on mainstream schools is shifting from adding new capacity to repairing and replacing existing buildings. New DfE capital spending also covers a big planned expansion in special school capacity and extra spending on colleges and children’s homes. 290 Institute for Government interview.

* Including non-mainstream schools, early-years and post-16 provision the total was £11.4bn.

Catch-up programmes are not likely to reach as many pupils as intended

In-person teaching was severely disrupted over the course of two academic years as a result of Covid,

302

Davies N, Hoddinott S, Fright M and others, Performance Tracker 2022/23: Spring update, Institute for Government, 23 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/performance-tracker-2022-23

while a sharp increase in absence rates since has further disrupted many pupils’ learning. More than one in six primary school pupils (17.2%) and more than one in four secondary school pupils (28.3%) are estimated to have been persistently absent in 2022–23 – defined as missing 10% or more of school sessions.

303

Department for Education, ‘Pupil attendance in schools: Week 29 2023’, GOV.UK, 10 August 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/pupil-attendance-in-schools/2023-week-29

This has been blamed on a number of factors, including attitudinal change following the pandemic.

304

Oral evidence, House of Commons Education Committee, HC 970, 16 May 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13160/html

,

305

Yeomans E, ‘Covid and strikes have normalised school truancy, says commissioner’, The Times, 1 June 2023, retrieved 20 June 2023, www.thetimes.co.uk/article/covid-and-strikes-have-normalised-school-truancy-says-commissioner-l5jv2qwrg

,

306

Weale, S, ‘Schools in England seeing more pupil absences on Fridays’, The Guardian, 8 March 2023, retrieved

4 August 2023, www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/07/schools-in-england-seeing-more-pupil-absences-on-fridays

The government has a £4.9bn package of education catch-up measures, announced in 2020 and 2021 and allocated between the 2020–21 and 2023–24 school years. 307 House of Commons Education Committee, Is the Catch-up Programme fit for purpose?: Fourth Report of Session 2021–22 (HC 940), The Stationery Office, 2022. This is significantly less than the roughly £15bn that had been recommended by the government’s education recovery commissioner. 308 Rachel Sylvester, Tweet, 2 June 2021, www.twitter.com/RSylvesterTimes/status/1399991919208509440 Most of the sum made available (£3.5bn) is allocated to schools, with the rest allocated to early-years and 16–19 education. 309 Comptroller and Auditor General, Education recovery in schools in England, Session 2022–23, HC 1081, National Audit Office, 2023.

Two of the main components of this support – the ‘catch-up’ and the ‘recovery’ premiums – have provided schools with £1.9bn of funding for general use, with limited conditions attached. 310 Department for Education, ‘Catch-up premium’, GOV.UK, 27 April 2021, retrieved 31 January 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/catch-up-premium-coronavirus-covid-19/catch-up-premium , 311 Department for Education, ‘Recovery premium funding’, GOV.UK, 28 September 2022, retrieved 31 January 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/recovery-premium-funding/recovery-premium-funding The other main component is the government’s £1.1bn National Tutoring Programme (NTP), launched in November 2020. 312 Comptroller and Auditor General, Education recovery in schools in England, Session 2022–23, HC 1081, National Audit Office, 2023, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/education-recovery-in-schools-in-england.pdf

The NAO noted in February 2023 that catch-up interventions designed by the DfE were informed by evidence, but expressed concern that disadvantaged pupils* – ostensibly the main focus of recovery efforts – were still exhibiting higher levels of learning loss than other pupils. 326 Comptroller and Auditor General, Education recovery in schools in England, Session 2022–23, HC 1081, National Audit Office, 2023, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/education-recovery-in-schools-in-england.pdf

Ofsted, the schools inspectorate, also carried out a review of the NTP based on visits to a sample of 63 schools during the scheme’s second year. This found that in more than half the schools, tutoring was strong, with tutoring in some of the other schools visited having strong features. However, in 10 of the schools tutoring was “haphazard and poorly planned”. Ofsted also noted that schools generally had not yet developed efficient means of assessing the impact of the tutoring. 327 Ofsted, ‘Independent review of tutoring in schools: phase 1 findings’, GOV.UK, 26 October 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-tutoring-in-schools-and-16-to-19-providers/independent-review-of-tutoring-in-schools-phase-1…

An estimated 3.8 million tutoring courses under the NTP had been started between its launch in 2020 and May 2023. 328 Department for Education, ‘National Tutoring Programme: Academic Year 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 20 April 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/national-tutoring-programme/2022-23 The government is forecasting that only 1 million courses will be delivered in 2023–24, the final year of the scheme, versus an earlier expectation of twice that, however – leading it to drop an overall target of 6 million courses taken over the life of the programme. 329 Institute for Government interview.

NTP funding is a subsidy towards the cost of tutoring, with schools having to find the rest of the cost from their general funding and the level of subsidy reducing over time. Lower forecast demand, therefore, suggests that schools either cannot afford to fund the balance, or are not seeing sufficient value in the tutoring.

* Defined as being eligible for free school meals in the previous six years.

Primary school attainment has dropped markedly since the pandemic

The government cancelled key stage 2 (KS2) assessments, covering pupils at the end of primary school, in 2020 and 2021. KS2 assessments resumed in 2022, with the results showing a fall in the percentage of pupils meeting the expected standard in reading, writing and maths from 65% in 2019 to 59% in 2022, driven by steep falls in maths and writing attainment. 330 Department for Education, ‘Key stage 2 attainment: National headlines, academic year 2021/22’, GOV.UK, 5 July 2022, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/key-stage-2-attainment- national-headlines/2021-22

In 2023, some 59% of pupils again met the expected standard in reading, writing and maths – though with reading results falling and maths and writing results improving.

331

Department for Education, ‘Key stage 2 attainment: Academic year 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 12 September 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/key-stage-2-attainment/2022-23

This leaves the government well behind on a target introduced in 2022: to get 90% of pupils at the expected standard in reading, writing and maths by 2030.

332

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Levelling Up the United Kingdom, CP 604, The Stationery Office, 2 February 2022, p. 187, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1052706/Levelling_Up_WP_HRES.pdf

Since assessments resumed after the pandemic, the gap in attainment between disadvantaged pupils and their better-off peers has also widened to levels last seen in 2012.

333

Department for Education, ‘Key stage 2 attainment: Academic year 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 12 September 2023,

https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/key-stage-2-attainment/2022-23

Given pupils who completed KS2 assessments in 2023 may have benefited from up to two and a half years of tutoring under the NTP, the results raise further questions about the effectiveness of this programme.

For secondary pupils, GCSE exams and other external assessments were also cancelled in 2020 and 2021 – with a major backlash in 2020 against plans to use an algorithm to set grades. GCSE grades were set instead by schools and regulators in 2020, and schools in 2021, following national guidelines, and were considerably higher than those in previous years. 334 Atkins G, Kavanagh A, Shepheard M, Pope T and Tetlow G, Performance Tracker 2021: Assessing the cost of Covid in public services, Institute for Government, 18 October 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/performance-tracker/performance-tracker-2021 GCSE exams also restarted in 2022, with results set between 2019 and 2021 levels, while in 2023 grades were allowed to return to pre-pandemic levels, with some grading protections to ensure they were not below 2019 levels. 335 Saxton J, ‘Ofqual’s approach to grading exams and assessments in summer 2022 and autumn 2021’, Ofqual, 30 September 2021, retrieved 10 July 2022, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/ofquals-approach-to-grading-exams-and-assessments-in-summer-2022-and-autumn-2021 , 336 Ofqual, ‘Looking ahead to GCSE, Level 1 and Level 2 vocational and technical qualifications results’, GOV.UK, 22 August 2023, retrieved 25 August 2023, https://ofqual.blog.gov.uk/2023/08/22/looking-ahead-to-gcse-level-1-and-level-2-vocational-and-technical-qualifications-results

These factors mean GCSE results are of little value when trying to compare the overall performance of the 2022 and 2023 cohorts to that of earlier cohorts. Alternative evidence on the attainment of secondary school pupils – the National Reference Test, taken by a sample of 16-year-olds each year – did not, however, find statistically significant changes in overall attainment in English and maths between 2017 and 2023 at most of the attainment levels measured in the test. 337 Burge B and Benson L, ‘National Reference Test Results Digest 2023’, National Foundation for Educational Research, 24 August 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1180184/NRT_Results_Digest_2023.pdf But similarly to KS2, GCSE results for 2023 have seen the gap in attainment between disadvantaged pupils and their non-disadvantaged peers reach its widest point since 2011. 338 Department for Education, ‘Key Stage 4 performance: Academic year 2022/23’, GOV.UK, 19 October 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/key-stage-4-performance-revised/2022-23

On the other main school accountability measure – inspection ratings – 90% of primary schools and 81% of secondary schools were rated as either being ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted as at 31 July 2023. 342 Ofsted, ‘Management information - state-funded schools - as at 31 July 2023’, GOV.UK, 11 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/monthly-management-information-ofsteds-school-inspections-outcomes This is higher than was the case before the pandemic, though with fewer outstanding ratings. 343 Ofsted, ‘Management information - state-funded schools - as at 31 Dec 2019’, GOV.UK, 11 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/monthly-management-information-ofsteds-school-inspections-outcomes This follows the removal of an exemption from inspection for schools holding this rating in 2020, with most of these schools dropping to a good rating when inspected. 344 Ofsted, ‘A return to inspection: the story (so far) of previously exempt outstanding schools’, GOV.UK, 22 November 2022, retrieved 17 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-inspections-statistical-commentaries-2021-to-2022/a-return-to-inspection-the-story-so-far-of-previously-exe…

- Topic

- Public services

- Department

- Department for Education

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government