Performance Tracker 2023: Criminal courts

Demand is becoming more complex, backlogs are at record highs, and productivity is declining

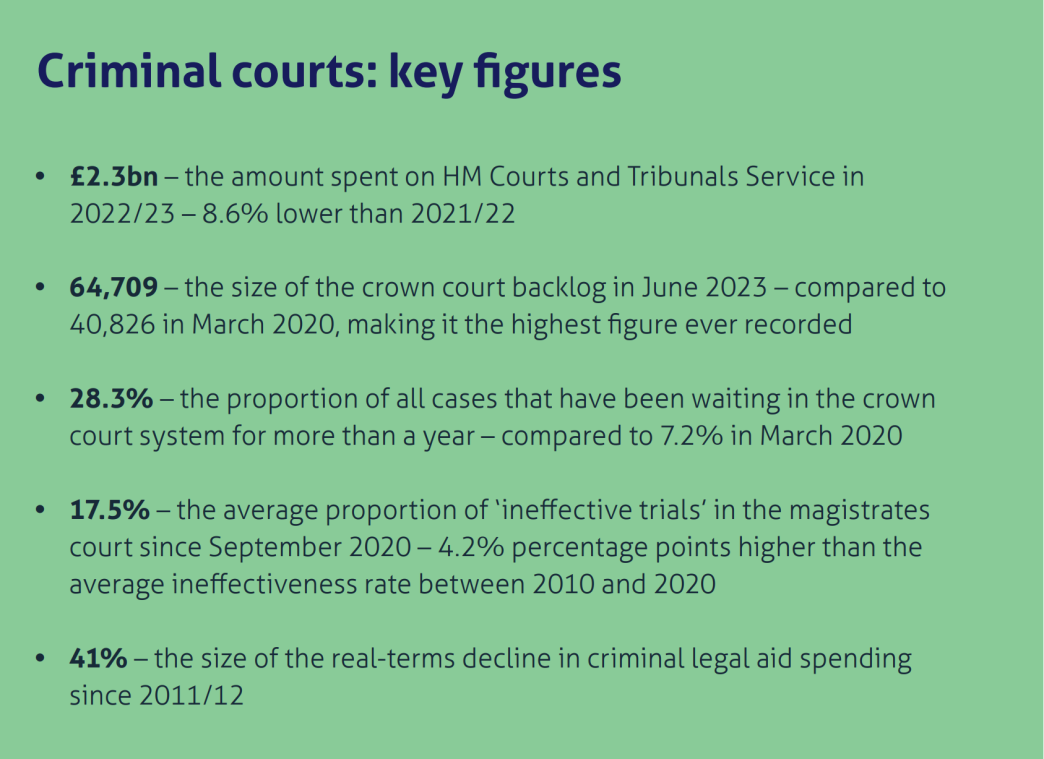

The twin effects of the pandemic and the 2022 barristers’ strike have severely affected the functioning of the criminal courts in recent years, with hearings delayed and the case backlog growing to record highs.

Magistrates’ courts have made good progress in starting to clear their backlog. This is a reflection of the largely procedural nature of many of the minor cases that enter these courts, also helped by the decline and slow growth in demand at the start of the pandemic.

The situation in the crown court – which conducts more serious or complex hearings and, crucially, jury trials – is much worse. Its case backlog reached a record 64,709 in June 2023. Adjusted for the complexity of cases in the backlog, which disproportionately comprises jury trials, this was equivalent to 89,937 cases. The backlog grew initially due to Covid-enforced court closures and social distancing, and then again in 2022 due to industrial action by criminal barristers.

These were exceptional events, but courts dealing with the most serious cases have also faced wider problems translating higher spending and more sitting days in recent years into greater throughput. As such, the crown court is facing a productivity crisis that has continued to increase the backlog. This has increased waiting times, with 28% of cases in the backlog waiting for over a year, and 10% waiting over two years. With demand projected to increase, this must change if backlogs are to be cleared and the court system is to operate efficiently.

Spending fell in 2022/23, and is set to continue falling

Real-terms spending on courts in England and Wales declined by 23.4% between 2010/11 and 2017/18. It then increased by 20% between 2017/18 and 2021/22, before falling by 10% in 2022/23.

The fall in 2022/23 is largely explained by a fall in non-cash expenditure – which includes provisions for future spending – with real-terms spending also eroded by high levels of inflation. Spending on the judiciary and staff fell by 3.4% in 2022/23.

Under the 2021 spending review, real-terms spending on courts (criminal and civil) was set to increase by around 4% per year to 2024/25. 54 Atkins G, ‘Spending review 2021: what it means for public services’, Institute for Government, 15 March 2021, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/explainer/spending-review-2021-what-it-means-public-services However, higher than expected inflation means that courts’ spending is now expected to fall by 2% in real terms between 2022/23 and 2024/25. (Unlike the NHS, schools and adult social care, criminal justice services were not provided with additional funding in the autumn statement 2022 to account for inflation.)

Demand is lower than before the pandemic in the magistrates but higher in the crown court, and is likely to rise in coming years

The best way to measure demand in criminal courts is to look at the number of cases they receive. All cases start their life in the magistrates’ courts; the most serious are then passed on to the crown court.

The number of new cases entering the magistrates’ court fell by 6.9% between 2012/13 and 2019/20. There was then a further, dramatic, fall in new cases in Q2 2020 with the onset of the pandemic (down 36.9%). Since then, demand has slowly increased but the number of cases received in 2022/23 was still 12.1% lower than in 2019/20. It is also lower than was implied by the government’s own model for the impact that the increase in the number of police officers would have on court demand. However, as discussed in the Police chapter, the number of charges increased by at least 8.9% in 2022/23. This is likely to lead to more cases entering the courts in future years.

Criminal cases are split into three main categories:

- summary: the least serious case type, comprising the vast majority of new cases

- either-way: cases whose severity means they can be processed in either the magistrates’ or crown court

- indictable only: the most serious cases, which can only be heard in the crown court

The pre-pandemic decline in new cases was driven by declines of 20.6% and 25.3% in more serious ‘either-way’ and ‘indictable’ cases (respectively) from 2012/13 to 2019/20. This was a consequence of fewer charges, increasing crime complexity and cuts in the Crown Prosecution Service’s budget. The decline in indictable cases also explains the decline in crown court demand. However, at the end of 2021 the trend of falling numbers of ‘either-way’ cases was reversed. The number of ‘either-way’ cases received by the magistrates’ courts grew by 16.5% between Q3 2021 and Q2 2023.

Before the pandemic, demand in the crown court fell more dramatically than in magistrates’ courts. In 2019/20 annual crown court receipts were 31.3% lower than in 2010/11. A sharp 45.2% drop at the start of the pandemic quickly recovered in the second half of 2020, and demand in 2022/23 was only 7.8% below the 2019/20 level. However, a more recent spike in crown court receipts – equating to a 13% growth since December 2022 – means demand has now surpassed pre-pandemic levels. This is partly attributable to a surge of cases following the reversal of magistrates’ extended sentencing powers – a measure that was introduced to relieve pressure on the crown court but which subsequently raised concerns about prison capacity. We expect this trend to continue, however, given the recent increase in charges.

Nor do the headline numbers tell the full story. The complexity of cases entering the crown court has also increased. For example, sexual offences – which require complex evidence handling and more sitting days, and have lower guilty plea rates than many other offences – comprised 10.3% of all the cases entering the crown court in Q2 2023. This proportion has been rising since Q2 2018, when such cases comprised 5.7% of cases – a 93.9% increase between these quarters. More broadly, the proportion of all defendants who plead not guilty (or enter no plea) was 26.9% in 2022/23, the highest level since 2018/19. 60 Ministry of Justice, ‘Criminal court statistics quarterly: April to June 2023’ (‘Crown Court plea tool’), retrieved 24 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/criminal-court-statistics-quarterly-april-to-june-2023 This too has pushed up the average length of trials. 61 Judiciary of England and Wales,The Lord Chief Justice’s Report 2023, September 2023, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/LCJ-annual-report-2023.pdf

Courts have struggled to process more cases and are less efficient

At the start of the pandemic, the combination of lockdowns and social distancing requirements severely limited courts’ ability to process cases, particularly jury trials. In the second quarter of 2020, the magistrates’ courts dealt with 59.3% fewer cases than the preceding quarter. Following this initial shock, magistrate courts gradually increased the number of cases processed, with the number in Q1 2023 just 3.8% lower than in Q1 2020. The magistrates’ courts were hampered by several strikes among legal advisers and court associates over the rollout of the Common Platform 62 Markson T, ‘Union announces more HMTS strikes over ‘unsustainable’ Common Platform’, Civil Service World, 21 November 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/hmcts-pcs-union-strike-common-platform-it-system-rollout-unsustainable; – a digital case management system that forms a key part of HMCTS’ reform programme 63 The Bar Council, ‘Access denied: The state of the justice system in England and Wales in 2022’, November 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.barcouncil.org.uk/resource/access-denied-november-2022.html#:~:text=A%20fair%20and%20just%20society,in%20our%20justice%20system%20today – from September 2022 to March 2023. Despite this, they have processed more cases than they have received in most quarters since the start of the pandemic. 64 Markson T, ‘Union ‘wins significant concessions’ that could end HMCTS dispute’, Civil Service World, 14 March 2023, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/hmcts-common-plaform-dispute-pcs-union-concessions;

In the crown court, processing was limited by the dual effects of the pandemic and the barristers’ strike. The pandemic initially caused a sharp 47.1% drop in the total number of cases that crown courts processed, including an almost total 97.5% fall in jury trials. After quickly recovering, last year’s industrial action had a further negative effect, causing a 20.2% drop in the number of cases processed between Q1 and Q3 2022.

Even outside of these crises – and despite increased funding since 2017/18 and an increase in sitting days (discussed below) – the number of cases processed has not surpassed pre-pandemic levels, and it declined in the most recent quarter. This suggests courts are operating less efficiently than in the past.

Several factors are contributing to this drop in productivity

One reason courts have struggled to process as many cases as they did before the pandemic is that they have become less efficient. The Ministry of Justice records all court cases that are listed for trial as having four potential outcomes:

- effective: the trial goes ahead as planned

- vacated: the trial is postponed ahead of the scheduled date (meaning another case can be listed instead)

- cracked: the trial does not need to go ahead, but this is only decided on the day

- ineffective: the trial does not happen on the day and must be rescheduled.

Since the pandemic, one of the most concerning trends has been the growth of ineffective cases in criminal courts. This is the worst outcome as far as efficiency is concerned, as it means court space goes unused while legal practitioners spend time preparing for cases that do not happen. In the magistrates’ courts, the proportion of ineffective trials averaged 13.3% per quarter from 2010 to 2020, compared to 17.5% since Q3 2020.

The situation is worse in the crown court, where quarterly rates of ineffectiveness averaged 18.6% from Q2 2021 to Q2 2023, up from 10.2% between 2010 and 2019. At the height of the barristers’ strike, such cases comprised a record 35.9% of all listed trials, driven by the unavailability of defence advocates. While the strike was the immediate cause of this, interviewees have stressed concern over the unavailability of legal advocates as a growing contributor of ineffectiveness; this was also cited by the Lord Chief Justice as a cause of court efficiency problems in 2021 and 2022. undefined Judiciary of England and Wales, The Lord Chief Justice’s Annual Report 2022, October 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.judiciary.uk/lord-chief-justices-annual-report-2022 Contributors to this have included the decline in sitting days – the number of days that the government funds for judges to hear cases – over several years and the poor relative remuneration of criminal legal work, both of which have reduced the market for criminal legal work. Interviewees stressed that reducing sitting days in particular has pushed barristers and solicitors into other areas of legal work.

Problems with buildings and technology have also reduced court efficiency. The Law Society has raised concerns over problems with the suitability of courts’ facilities 70 The Law Society, ‘Five steps to resolve the backlogs in our courts’, 19 December 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.lawsociety.org.uk/campaigns/court-reform/news/five-point-plan-to-fix-court-backlog while the Bar Council has described instances in which leaks, infestations and collapsing walls have blighted court space. 71 The Bar Council, ‘Access denied: The state of the justice system in England and Wales in 2022’, November 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.barcouncil.org.uk/resource/access-denied-november-2022.html#:~:text=A%20fair%20and%20just%20society,in%20our%20justice%20system%20today However, these issues have had less impact than the insufficiency of the workforce to make use of existing space. 72 Institute for Government interview.

Similarly concerning is courts’ inability to make use of available sitting days. The government (which funds sitting days) began to reduce the number of sitting days from 2015, and Covid restrictions reduced these further in 2020 to the lowest recorded level (69,100 compared to 113,800 in 2015). 73 Ministry of Justice, ‘Civil justice statistics quarterly: January to March 2023’ (Royal Courts of Justice Annual Tables – 2022 (‘Table 9.2’)), retrieved 24 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/civil-justice-statistics-quarterly-january-to-march-2023 Sitting days have since grown to 102,600 in 2022. However, the amount of time spent hearing cases has been much lower since the onset off the pandemic; 2.7, 2.9 and 2.8 hours per sitting day in 2020, 2021 and 2022 respectively, compared to 3.6, 3.5 and 3.5 hours in 2017, 2018 and 2019 respectively.

This means courts are making less use of the available time. Covid restrictions may have played a part in this, as courts listed cases less aggressively than in the past (meaning that when cases were cracked, there was often no other case to take its place). 74 Ministry of Justice, ‘Civil justice statistics quarterly: January to March 2023’ (Royal Courts of Justice Annual Tables – 2022 (‘Table 9.2’)), retrieved 24 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/civil-justice-statistics-quarterly-january-to-march-2023 Similarly, greater use of remote hearings – scheduled for specific times – may be extending the time between hearings, leading to less efficient use of sitting days.

The increased complexity of cases may also have exacerbated listing problems. These cases have less predictable lengths, and it is harder to schedule cases to make best use of sitting days when a greater proportion of cases are unpredictable in this way. Concerningly, given our expectation that the number of complex cases will continue increasing, this means that productivity may continue to decrease.

This declining efficiency, coupled with rising demand, has led to the crown courts receiving more cases than they have been able to process for the last four years and the size of the case backlog growing dramatically.

A huge crown court backlog will continue to hamper the smooth functioning of the service

In the magistrates’ courts, the backlog reached 422,156 cases in Q2 2020, some 40.8% higher than in December 2019 and the highest since the data was first published in 2012. Magistrates’ courts processing capacity has grown more quickly than the growth in demand since 2020 and as a result, the backlog has been cut by 18.2% and is now 15.2% higher than in December 2019. Several factors have contributed to this. First, many cases are less complex, allowing greater use of remote hearings. Second, many cases can be heard with a single magistrate and legal adviser (the single justice procedure).

If defendants plead not guilty, cases in the crown court require jury trials. These became more difficult to conduct during the pandemic, meaning the crown court was more substantially affected by the pandemic than the magistrates courts were. Indeed, were no additional cases to enter the court system, the current magistrates’ backlog could be cleared in less than three months; the estimate for the crown court is more than seven months.

The number of cases waiting in the crown court had started to increase before the pandemic because of the government’s decision to reduce sitting days. 77 House of Commons Justice Committee, Court Capacity: Sixth Report of Session 2021-22, HC69, April 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/21999/documents/163783/default This caused the backlog to grow by close to a quarter between December 2018 and March 2020 (24.1%). The pandemic worsened things even more dramatically, growing the backlog by a further 48.6% between March 2020 and June 2021. A subsequent decline was reversed by the industrial action among criminal barristers, which pushed the outstanding caseload in the crown court to a record high of 62,844 in September 2022.

Concerningly, progress in reducing the crown court backlog was limited between September 2022 and March 2023, and has since reversed. Even before this, the government was set to miss its target to reduce the backlog to 53,000 by March 2025 by years. 78 HM Treasury, Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021: A stronger economy for the British people, HC 822, 27 October 2021, retrieved 24 October 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1043688/Budget_AB2021_Print.pdf Even if the government were to meet this target, the backlog would still be 30% higher than on the eve of the pandemic.

However the backlog is even worse than the headline figure suggests. Because courts struggled to hold jury trials during the pandemic, the composition of the backlog has shifted to include a much higher proportion of cases requiring jury trials. As such, the case mix in the backlog is much more complex than at the start of the pandemic. Accounting for this additional complexity, the backlog in Q2 2023 was equivalent to 89,937 cases, compared to the official figures of 64,709. This means that on the basis of how much work it will take to clear, the current backlog is actually 136.9% larger than at the start of the pandemic.

Backlogs have contributed to the worst waiting times on record, severely delaying justice

Larger backlogs mean victims and defendants waiting for more time until they can have their cases closed. This is particularly apparent in the crown court. Over the six years before the pandemic, between 40% and 50% of crown court cases were dealt with in less than three months. This proportion declined during the pandemic and reached its worst recorded level in Q4 2022, when only 27.8% of cases were dealt with in that time frame.

The flip side of this is that a greater proportion of cases now take much longer to be processed. Since the start of the pandemic, the proportion of cases taking over a year has increased from 7.2% to 28.3%. In absolute terms, this means there are now over six times as many cases taking more than a year than there were in March 2020.

Longer waiting times mean people experience a poorer quality of justice. People’s memories fade over time and it becomes increasingly likely that victims (especially of the most serious offences) withdraw from cases. 86 House of Commons Justice Committee, Court Capacity: Sixth Report of Session 2021-22, HC69, April 2022, p. 21, retrieved 24 October 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/21999/documents/163783/default , 87 Dearden L, ‘“Overwhelmed” justice system failing victims of crime, CPS chief warns’, Independent, 2 January 2023, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/criminal-justice-system-delays-overloaded-b2250604.html The former victims commissioner attributed this to victims’ inability to process trauma, arguing that ‘justice delayed is justice denied’. 88 Baird V, Dame, ‘Courts backlog: Justice delayed is justice denied’, Victims Commissioner, 21 July 2021, retrieved 24 October 2023, https://victimscommissioner.org.uk/news/annual-report-courts-backlog/#:~:text=Delays%20prevent%20victims%20processing%20their%20trauma%2C%20with%20th… And the longer waiting times have a wider impact on the criminal justice system too, as they mean defendants spend longer in custody awaiting trial – so placing even more pressure on prisons (see the Prisons chapter).

The government must contend with an increasingly dissatisfied workforce

Courts’ ability to process cases depends not only on the number of sitting days but also the number of available legal practitioners, including magistrates, judges and barristers, as well as other court staff. This remains a significant problem.

As noted, the criminal courts system was severely disrupted by the barristers’ strike, which came to an end in October 2022 after the government extended a 15% rate rise to most criminal cases. 89 Casciani D and Burns J, ‘Criminal barristers vote to end strike over pay’, BBC News, 17 October 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-63198892 Despite this, we have heard that many of the problems facing barristers (including capacity still being too limited and barristers being overstretched) have worsened over the last year. 90 Institute for Government interview. This is consistent with the problems identified in the Bellamy Review of legal aid, which heard that retention of experienced barristers is a significant problem. 91 Bellamy C, Sir, Independent Review of Criminal Legal Aid, 29 November 2021, retrieved 24 October 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1041117/clar-independent-review-report-2021.pdf Real-terms spending on criminal legal aid has declined by 43% since 2011/12 , which has led barristers and solicitors to increasingly diversify their practice away from criminal work, a trend exacerbated by the pandemic. Overall, there was a 9.8% decline in the number of full-time criminal barristers* between 2017/18 and 2021/22. 92 Data provided by the Bar Council.

The work of courts has also been impeded by a shortage of other key staff groups. Magistrate numbers have fallen significantly in recent years. In 2021/22, there were fewer than half the number of magistrates than in 2010/11 (down 53.6%) due to recruitment freezes. A national recruitment campaign that aimed to boost magistrate numbers by 4,000 was launched in January 2022, and contributed to an increase of 830 magistrates between 2021/22 and 2022/23, a 7% increase. 96 Ministry of Justice, ‘Magistrate recruitment campaign launched’, Press release, 24 January 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/magistrate-recruitment-campaign-launched This is the first increase since 2010/11, although magistrate numbers are still over 50% lower. 97 Judiciary of England and Wales, The Lord Chief Justice’s Annual Report 2022, October 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.judiciary.uk/lord-chief-justices-annual-report-2022

The government has also attempted to increase judicial capacity over the last year, including by allowing certain district and High Court judges to sit in the crown court and by raising the judicial retirement age by five years (which also applies to magistrates). 98 Judiciary of England and Wales, The Lord Chief Justice’s Annual Report 2022, October 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.judiciary.uk/lord-chief-justices-annual-report-2022 Despite this, the number of FTE fee-paid judges only increased by 15 over the last year, while the headcount of salaried judges declined by 13, with both below 2010/11 levels.

Judicial capacity has still been described by the Lord Chief Justice as an ‘acute problem’, with shortages of circuit judges** in particular affecting London and the Midland crown court circuit. 102 Judiciary of England and Wales, The Lord Chief Justice’s Annual Report 2022, October 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.judiciary.uk/lord-chief-justices-annual-report-2022 In recent recruitment rounds for circuit and district judges, the Judicial Appointments Commission has been unable to fill more than 84% of advertised vacancies, with one district judge round only filling 67% of vacancies. undefined House of Commons Justice Committee, Appointment of the Chair of the Judicial Appointments Commission: Sixth Report of Session 2022-23, HC 925, 7 December 2022, retrieved 24 October 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/31912/documents/179258/default

We have also been told by several interviewees that morale is low across the judiciary. This seems to be borne out by survey data published in March 2023, which suggests that 55% of salaried judges’ morale is affected by salary issues; this is 4 percentage points higher than 2020. 103 Thomas C (Prof, KC), ‘2022 UK Judicial Attitude Survey: Salaried judges and fee-paid judicial office holders in England & Wales Courts and UK Tribunals’, UCL Judicial Institute, 28 March 2023, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/England-Wales-UK-Tribunals-JAS-2022-Report-for-publication.pdf Similarly two-thirds of salaried judges claim that working conditions were worse in 2022 than two years previously (compared to one-third for fee-paid judges). 104 Thomas C (Prof, KC), ‘2022 UK Judicial Attitude Survey: Salaried judges and fee-paid judicial office holders in England & Wales Courts and UK Tribunals’, UCL Judicial Institute, 28 March 2023, retrieved 24 October 2023, www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/England-Wales-UK-Tribunals-JAS-2022-Report-for-publication.pdf

* Barristers that self-declared to the Bar Council that at least 80% of their gross fee income in the respective year came from criminal work. This work could be split between public and private criminal work (although they all received some income from public funding).

** Judges that sit in crown and county courts in a given jurisdiction.

- Topic

- Public services

- Department

- Ministry of Justice

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government