Performance Tracker 2023: General practice

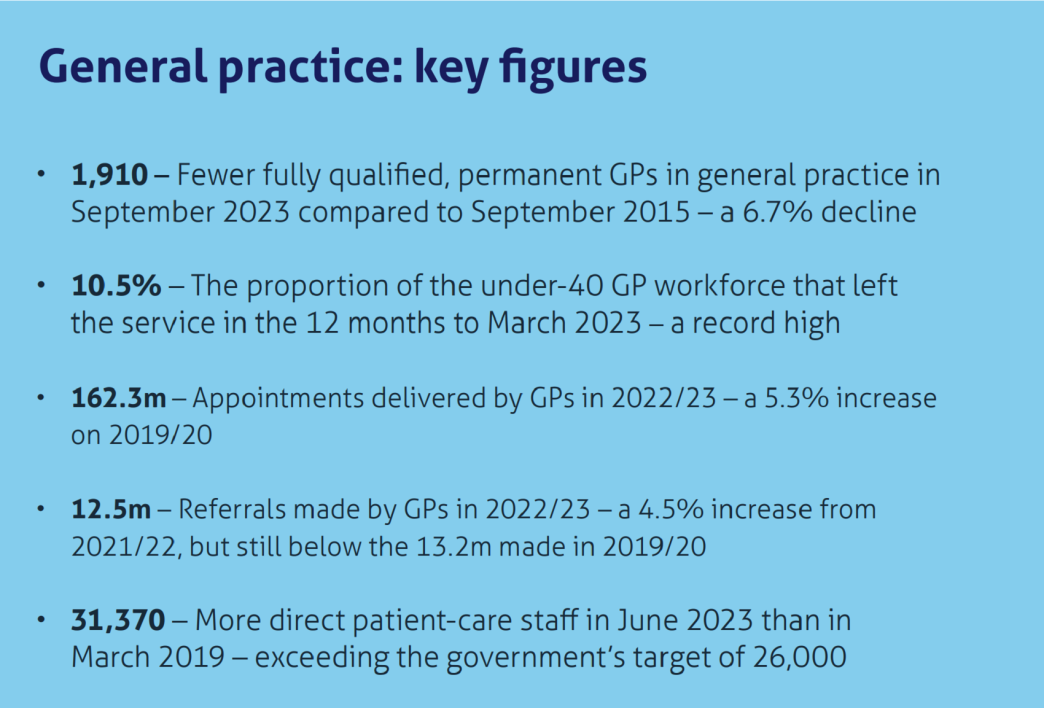

Despite a declining workforce, GPs are delivering more appointments than ever, though this may be increasing workloads and burnout.

General practice is delivering more appointments than ever. This is partly because of the government’s successful recruitment of more than 29,000 additional direct-patient care staff – fulfilling a manifesto commitment – but also because GPs themselves are providing more appointments, even as the number of fully qualified, permanent GPs continues to fall. This is in contrast to secondary care, chiefly hospitals, where the post-pandemic puzzle has been why more staff are delivering less activity on some measures than in 2019/20.*

Despite this record activity there is still not enough capacity to meet demand, with patients struggling to access appointments. In response, the government published its Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care in May 2023.** It is still too early to tell if that plan will have the desired effect, but it at least recognises some of general practice’s problems, such as historic underinvestment in capital: it contains a proposal to upgrade practices’ telephony systems.

The government is not taking a similar approach to all elements of general practice funding. It has remained wedded to funding levels agreed in 2019, despite recent inflation being far higher than predictions at the time, and has ruled that the recent uplift in GPs’ salaries must be paid for by reallocating funding from elsewhere in the NHS.*** The BMA’s General Practitioners Committee (GPC) threatened to ballot on industrial relations in response, but has since backed down in anticipation of a new contract in 2024/25.

As elsewhere in public services, high workloads are adding to the stress of the job for GPs and are likely contributing to growing numbers leaving general practice. Retention issues are particularly acute among younger GPs, with record numbers of GPs aged under 40 leaving general practice in the 12 months to March 2023 – there are now fewer GPs in this age group than at any other point on record. And while the NHS has recruited record numbers of GP trainees, not all stay in general practice after receiving their qualifications. Resolving the crisis in the GP workforce should remain the government’s top priority for general practice.

* Freedman S and Wolf R, The NHS productivity puzzle, Institute for Government and Public First, June 2023, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/nhs-productivity

** NHS England, ‘Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care’, 9 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/delivery-plan-for-recovering-access-to-primary-care/

*** Department for Health and Social Care, ‘NHS staff receive pay rise’, press release, 13 July 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/nhs-staff-receive-pay-rise

Spending and funding

Spending on general practice increased in 2021/22

Including Covid measures, spending on general practice rose by 4.2% in real terms in 2021/22, bringing the cash total to just over £15bn. Covid accounted for just under £800m (5.3%) of that total, and grew by 10.2% in real terms in 2021/22. This extra spending was primarily driven by increased spending on the vaccine programme, which rose from £333.9m in 2020/21 to £727.0m in 2021/22 – an increase of 112.1%.

Excluding this spending, the NHS increased its spending on general practice by 3.9% in real terms in 2021/22. But growth in spending was not distributed equally across all parts of general practice.

Spending on primary care networks (PCNs, organisations that the NHS launched in 2019 as part of the NHS Long Term Plan, designed to improve cooperation between practices and other parts of the health and care system) 248 Baird B and Beech J, ‘Primary care networks explained’, blog, The King’s Fund, 20 November 2020, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/primary-care-networks-explained grew more quickly than any other area of spending in 2021/22. The budget for PCNs grew from £568.4m in 2020/21 to £1.0bn in 2021/22 – an increase of 74.3% in real terms. Excluding Covid spending, the proportion of investment in general practice spent on PCNs has risen from 2.0% in 2019/20 (the first year PCNs existed) to 7.1% in 2021/22.

Excluding PCNs and Covid gives a better picture of the funding available for core general practice services, and shows that the NHS increased spending on GP services by just 0.4% in real terms in 2021/22.

The 2023/24 GP contract does not increase funding in line with inflation

The relationship between general practice, NHS England and the government is different to other parts of the health system. Practices effectively operate as small, independent businesses which the NHS contracts to provide services. 261 Beech J and Baird B, ‘GP funding and contracts explained’, blog, The King’s Fund, 11 June 2020, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/gp-funding-and-contracts-explained The NHS reimburses practices for the services they deliver largely depending on the size and the composition of their patient lists with, for example, older patients and patients with higher needs attracting more funding. The 2023/24 financial year is the last of the current five-year GP contract that started in 2019/20 and which was negotiated by NHS England and the British Medical Association (BMA, the union that represents doctors) in 2018 and early 2019. 262 NHS England, ‘Investment and evolution: A five-year framework for GP contract reform to implement The NHS Long Term Plan’, 31 January 2019, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/gp-contract-five-year-framework/

When a contract is agreed, GP partners – who own and manage GP practices – take on a certain amount of personal liability to deliver those services. The expense of running a practice comes out of the income practices receive from the GP contract, and GP partners pay themselves after other expenses (the largest part of which is other practice staff’s salaries) 263 Beech J and Baird B, ‘GP funding and contracts explained’, blog, The King’s Fund, 11 June 2020, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/gp-funding-and-contracts-explained have been met.

Over the last two years, the BMA GPC and NHS England have disagreed about the level of funding that the current GP contract provides. The BMA thinks that NHS England (NHSE) should have provided an uplift to help alleviate “pressures being faced by GPs and their teams” 264 British Medical Association, ‘GP contract changes England 2022/23’, BMA.ORG.UK, 10 March 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.bma.org.uk/pay-and-contracts/contracts/gp-contract/gp-contract-changes-england-202223 that have arisen from inflation. For its part, NHSE and the government think that general practice should see out the contract that they previously agreed. As it stands, NHSE has gone ahead with the previously agreed contract in both 2022/23 and 2023/24, which the BMA has labelled an “imposition of an ‘insulting’ and ‘inadequate’ contract”. 265 Tonkin T, ‘Contract imposition forces GPs to consider all options in response’, blog, British Medical Association, 10 March 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/contract-imposition-forces-gps-to-consider-all-options-in-response

There is some merit to the government’s argument. As independent contractors, GPs should be expected to take on risk when they agree to a new contract. There are, however, arguments against this decision and 2023 is clearly different to 2019. First, general practice worked through a global pandemic. That led, in some instances, to the government imposing new requirements on general practice without providing sufficient additional funding. For example, in September 2022, the government announced that GPs would have to provide appointments to patients within two weeks of them first requesting one. 266 Department of Health and Social Care, ‘Our plan for patients’, 22 September 2022, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/our-plan-for-patients/our-plan-for-patients There has also been a shift towards more remote appointments, and a general rise in costs. Some of these changes are funded – for example, the government will provide £240m of funding to shift practices to a cloud-based telephony system 267 NHS England, ‘Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care’, 9 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/delivery-plan-for-recovering-access-to-primary-care-2/ – but many are not.

Second, there has been a bout of above-forecast inflation which has driven up the cost of providing GP services. Despite that, the government chose largely to stick to the cash funding levels agreed in 2019. 268 NHS England, ‘Investment and evolution: A five-year framework for GP contract reform to implement The NHS Long Term Plan’, 31 January 2019, retrieved 18 October 2023, p.51, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/gp-contract-2019.pdf This means that the contract baseline increased by only 2.5% in 2022/23 and will increase by 2.7% in 2023/24, 269 Swift J, ‘GP Contract changes 2023/24: what you need to know’, blog, NHS Confederation, 9 March 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.nhsconfed.org/publications/gp-contract-changes-202324-what-you-need-know despite economywide inflation (as measured by the GDP deflator) increasing by 6.6% 270 GOV.UK, ‘GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP June 2023 (Quarterly National Accounts)’, GOV.UK, 30 June 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/gdp-deflators-at-market-prices-and-money-gdp-june-2023-quarterly-national-accounts in 2022/23 and being forecast to increase by 2.5% in 2023/24. 271 Office for Budget Responsibility, ‘Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2023’, 15 March 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2023/ At the time that the contract was agreed, the GDP deflator was not forecast to rise above 2% in any year of the contract, 272 GOV.UK, ‘GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP June 2023 (Quarterly National Accounts)’, GOV.UK, 30 June 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/gdp-deflators-at-market-prices-and-money-gdp-december-2018-quarterly-national-accounts meaning that the contract baseline would have increased by 2.1% in real terms by 2023/24, compared to 2018/19.

Instead, the contract baseline is now forecast to be 5.1% lower in real terms than in 2018/19. In addition wages, a major cost to practices, are likely to rise faster than inflation in 2023/24. The government has agreed to fund the increase in salaried GPs’ pay, but any increases for other practice staff will need to come out of existing budgets. This will in turn mean less funding available for other parts of general practice – but will be hard to avoid given the risk of staff leaving for better pay in, for example, secondary care.

The government’s line that GPs should honour the contract they agreed to in 2019 is short-sighted. Maintaining such a hard line in the face of obvious budgetary pressures risks worsening the problem of retention in general practice, and losing more of the workforce. That will make it much harder for the government to provide a politically acceptable standard of primary care.

Recent pay increases still leave GPs worse off than in 2006/07

There has been a long-term trend of declining pay for both GP partners and salaried GPs.[1] On the eve of the pandemic GP partner pay was already some 23.5% lower in real terms than 2006/07, and salaried GPs’ pay was 17.6% lower.

Since then there has been an increase for both staff groups. GP partner pay increased by 12.0% in real terms between 2019/20 and 2020/21, and by a further 7.4% in 2021/22. In the first year of the pandemic, this was mostly due to Covid support money, increased income from the Covid vaccine programme (some of which continued into 2021/22) and a reduction in costs such as locum expenses during the first lockdown. Despite those large recent pay increases, GP partner pay was still 8% lower in real terms in 2021/22 than in 2006/07. This is likely to make GP partnership less attractive at a time when the number of GP partners is already falling – a trend which could lead to more practice closures, as explored in more depth below.

Pay for salaried GPs has also risen since the onset of the pandemic, by 2.0% in real terms between 2019/20 and 2021/22.[1] The agreed pay deals in 2022/23 and 2023/24 will further increase pay in real terms, but will still leave it 7.6% lower in real terms than in 2006/07. Other than in 2023/24, when part of the uplift for salaried GPs was funded, GP practices have had to pay for recent pay uplifts out of the GP contract.

The forecast increase in 2023/24 for salaried GPs comes following a government decision to increase their pay by 6% in that year,

308

Department of Health and Social Care, ‘NHS staff receive pay rise’, press release, 13 July 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/nhs-staff-receive-pay-rise

after initially recommending a 2.1% pay increase.

309

NHS England, ‘Submission to the Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration: Evidence for the 2023/24 pay round’, 11 January 2023, p.46, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/B2025-nhs-england-submission-to-the-review-body-on-doctors-and-dentists-2023-24.pdf

Importantly, the GP contract will be uplifted to account for this higher pay settlement, though it does not seem that this is additional funding for the NHS from the government, but rather money that is being reallocated from other parts of general practice.

310

Department of Health and Social Care, ‘NHS staff receive pay rise’, press release, 13 July 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/nhs-staff-receive-pay-rise

The prospects for other practice staff are not so positive. The GP contract allows for a 2.1% pay rise for other practice staff in 2022/23 and 2023/24

311

Colivicchi A, ‘Salaried GPs and practice staff can only expect 2.1% pay rise this year, NHS England warns’, Pulse Today, 6 February 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/practice-personal-finance/salaried-gps-and-practice-staff-can-only-expect-2-1-pay-rise-this-year-nhs-england-warns/

– however this is against private sector wages increasing by around 7% in 2022

312

Office for National Statistics, ‘Average weekly earnings in Great Britain: March 2023’, 14 March 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/averageweeklyearningsingreatbritain/march2023

and a forecast 5.5% in 2023.

313

Bank of England, ‘Monetary Policy Report - May 2023’, 11 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2023/may-2023

More comparable, though, are the increases that the government has given to non-medical staff who work in hospitals. Those staff have received pay increases of 4.7% in 2022/23 and will receive a 5.2% increase on average in 2023/24, in addition to one-off payments worth 6% of their salary in 2022/23.

314

Hoddinott S, ‘A welcome NHS pay deal has taken too long to reach’, blog, Institute for Government, 17 March 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/nhs-pay-deal

In short, pay increases in general practice are not competitive with either the wider economy or other parts of the NHS, posing a risk to staff retention. This means that funding for general practice is not sufficient to provide all staff with competitive pay increases without imposing cuts on other areas of primary care.

Dissatisfaction with the GP contract has led the BMA to threaten balloting GPs on industrial action,

315

Colivicchi A, ‘BMA gives Government list of demands to meet to avoid GP industrial action’, Pulse Today, 22 March 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/breaking-news/bma-gives-government-list-of-demands-to-meet-to-avoid-gp-industrial-action/

though it has since backed down from that position in anticipation of a new contract in 2024/25.

316

Lind S, ‘BMA will not ballot GPs on industrial action over contract imposition’, Pulse Today, 27 April 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/breaking-news/bma-will-not-ballot-gps-on-industrial-action-over-contract-imposition/

Still, the possibility of industrial action hangs over general practice, especially as colleagues in other NHS services continue to take to the picket lines. A likely general election in 2024 adds further complications to negotiations. GP leaders will want to agree a contract with a new government, with reports that this could mean that they will push for a one-year holding contract to bridge the gap between 2023/24 and 2025/26, when the longer-term contract would start.

317

Bower E, ‘New GPC chair sets out ambitions for expected one-year GP contract in 2024/25’, GP Online, 11 August 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gponline.com/new-gpc-chair-sets-ambitions-expected-one-year-gp-contract-2024-25/article/1833019

GPs often work in cramped and poorly maintained premises with outdated IT

It is more difficult to assess the sufficiency of capital spending in general practice than in other services, as there is little publicly available data to show the quality of the estate, IT systems, or equipment.

318

Department of Health and Social Care, ‘NHS Property and Estates: Why the estate matters for patients’, GOV.UK, March 2017, p.11, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/607725/Naylor_review.pdf

Much of the estate is not owned by the NHS itself: the May 2022 Fuller Stocktake reported that only 14% of premises are owned by NHS Property Services, with the rest owned by GPs themselves and third parties.

319

NHS England, ‘Next steps for integrating primary care: Fuller stocktake report’, May 2022, p.23, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/next-steps-for-integrating-primary-care-fuller-stocktake-report.pdf

Despite the difficulties in accessing good data, the indications from information that is publicly available and our own interviews are that capital investment in general practice has been insufficient to ensure the primary care estate meets the requirements of a modern health service.

A survey of clinicians shows that one in four GPs are treating patients in premises that are not fit for purpose.

320

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘4 in 10 GPs working in premises ‘not fit for purpose’, says College survey’, press release, 17 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/News/Practice-Premises-Survey

Lack of space seems to be a particular issue: 88% of GPs say that there are not enough consulting rooms;

321

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘4 in 10 GPs working in premises ‘not fit for purpose’, says College survey’, press release, 17 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/News/Practice-Premises-Survey

66% say that the lack of space makes it harder to train new GPs;

322

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘4 in 10 GPs working in premises ‘not fit for purpose’, says College survey’, press release, 17 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/News/Practice-Premises-Survey

and 84% report that estate space restricts how many GP trainees they can take on.

323

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Fit for the future: Reshaping general practice infrastructure in England’, RCGP.ORG.UK, 17 May 2023, p.10, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/2aa7365f-ef3e-4262-aabc-6e73bcd2656f/infrastructure-report-may-2023.pdf

One GP responding to a Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) survey said: “Lack of space is our biggest constraint.

There is no funding to address accommodating physios, mental health, and social care practitioners, [this] has led to GPs working in cupboards – it’s hopeless”.

324

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Fit for the future: Reshaping general practice infrastructure in England’, RCGP.ORG.UK, 17 May 2023, p.7, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/2aa7365f-ef3e-4262-aabc-6e73bcd2656f/infrastructure-report-may-2023.pdf

The lack of capital investment is not, however, limited to the estate. IT systems in general practice are often out of date. Almost half (46%) of respondents to the RCGP’s survey say that PC or laptop software is not fit for purpose

325

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Fit for the future: Reshaping general practice infrastructure in England’, RCGP.ORG.UK, 17 May 2023, p.12, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/2aa7365f-ef3e-4262-aabc-6e73bcd2656f/infrastructure-report-may-2023.pdf

and more than a third of general practice staff say that their broadband is not of an acceptable standard.

326

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Fit for the future: Reshaping general practice infrastructure in England’, RCGP.ORG.UK, 17 May 2023, p.12, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/2aa7365f-ef3e-4262-aabc-6e73bcd2656f/infrastructure-report-may-2023.pdf

It is not just the quality of IT within practices that prevents more efficient working – close to two thirds (65%) of staff say that their ability to exchange information with the wider health service is not fit for purpose, driven by underinvestment in software that makes it easier to share information.

327

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Fit for the future: Reshaping general practice infrastructure in England’, RCGP.ORG.UK, 17 May 2023, p.13, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/2aa7365f-ef3e-4262-aabc-6e73bcd2656f/infrastructure-report-may-2023.pdf

The reasons for this are complex. The NHS argues that responsibility for capital investment in primary care lies with GPs, given their status as independent contractors. As such, GPs should provide and maintain an appropriate estate and ensure IT systems are fit for purpose. While this is technically true, the reality is more nuanced. GPs are not well suited – either financially or from a logistical perspective – to make the required level of capital investment in general practice.

On financing, the GP contract is a poor mechanism for allocating capital investment. First, unlike how funding is allocated to government departments, there is no ring-fencing for capital investment in the amount provided to GPs, meaning that capital directly competes with other funding pressures, such as a requirement to increase practice staff wages. The result is that, as a government review of general practice premises policy found, there is “a lack of clarity or understanding around the responsibilities of all parties involved in estate ownership and occupancy” which can mean that property is not maintained to the level it should be.

328

NHS England and Improvement, ‘General Practice Premises Policy Review’, June 2019, p.11, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/general-practice-premises-policy-review.pdf

It could be argued that GP partners – as the holders of GP contracts – should reduce their earnings to fund investment. But on an individual practice scale, that may not generate enough cash for the type of investment required[1] and would likely further harm GP partner recruitment and retention at a time of declining numbers, as discussed below.

GPs are also somewhat at the mercy of national policy making. For example, the problem of limited and inappropriate estate space has been compounded by the expansion of multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs), which includes the addition of 29,103 direct patient care (DPC) staff (discussed more below). But that policy has not been accompanied by concomitant intention or funding to expand the estate, with de facto responsibility falling to practices to accommodate them. 329 Baird B, Lamming L, Bhatt R and others, Integrating additional roles into primary care networks, The King’s Fund, February 2022, p.16, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-02/Integrating%20additional%20roles%20in%20general%20practice%20report%28web%29.pdf This means that the government is not using those new staff as effectively as they might otherwise be, eroding value for money.

The Fuller stocktake asserts that when it comes to utilising multi-disciplinary teams, the primary care estate is “not up to scratch”

330

NHS England, ‘Next steps for integrating primary care: Fuller stocktake report’, May 2022, p.23, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/next-steps-for-integrating-primary-care-fuller-stocktake-report.pdf

and that the NHS needs to develop “hubs within each neighbourhood and place to co-locate integrated neighbourhood teams… for the provision of more integrated services”.

331

NHS England, ‘Next steps for integrating primary care: Fuller stocktake report’, May 2022, p.27, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/next-steps-for-integrating-primary-care-fuller-stocktake-report.pdf

As an example of the kind of investment needed, it uses the case study of a health centre that was developed in Waltham Forest through a partnership between the local authority and the local NHS, at a cost of £1.4m.

332

NHS England, ‘Next steps for integrating primary care: Fuller stocktake report’, May 2022, p.24, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/next-steps-for-integrating-primary-care-fuller-stocktake-report.pdf

That scale of investment and coordination of stakeholders is far beyond the ability of any practice – or even small group of practices – to deliver, either financially or logistically.

The same argument holds for investment in IT. Practices are responsible for providing hardware for their employees, and often as noted fail to provide an adequate standard. But it is beyond their ability to provide systems that, for example, enable data sharing between different parts of the NHS – an outcome that requires large scale investment and coordination. Even when individual practices can purchase their own IT systems, this is unlikely to represent good value for money; the Fuller stocktake again argues that, when procuring IT systems, integrated care systems could “leverage their larger scale and purchasing power to improve value for money and quality of service”.

333

NHS England, ‘Next steps for integrating primary care: Fuller stocktake report’, May 2022, p.26, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/next-steps-for-integrating-primary-care-fuller-stocktake-report.pdf

The government has recognised this and taken some steps to address the issue. On estates, it has proposed investing in six “Cavell centres”, intended to provide appropriate space for the integration of primary, community, and social care services. But the Health Services Journal reported in March 2023 that NHSE had ordered that work on the centres be stopped until a national business case had been approved.

334

Launder M, ‘Exclusive: NHSE halts ‘pioneer’ health centres due to lack of capital’, Health Services Journal, 21 March 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.hsj.co.uk/primary-care/exclusive-nhse-halts-pioneer-health-centres-due-to-lack-of-capital/7034482.article

On IT systems, the government used the Delivery Plan for Recovery Access to Primary Care to allocate £240m over 2023/24 and 2025/25 “for new technologies and support offers for primary care networks”,

335

NHS England, ‘Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care’, 9 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/delivery-plan-for-recovering-access-to-primary-care-2/

which includes some portion going to improved cloud telephony for practices. This is welcome, but is targeted at a very narrow, patient-facing part of the service and will not address many of the IT issues laid out above. It also comes at the expense of spending elsewhere in the health and care sector, as the government chose to “retarget” funding rather than make new money available.

336

NHS England, ‘Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care’, 9 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/delivery-plan-for-recovering-access-to-primary-care-2/

One interviewee suggested that decision making for capital investment in primary care could be improved if it was shifted upwards from GP partnerships to integrated care boards (ICBs), who would be best placed to make decisions about how to coordinate care between community care, primary care, mental health, and adult social care providers. This would also allow ICBs to leverage their size to achieve better value for money.

Demand

General practice does not have enough capacity to meet demand

Anecdotally, demand for GP services has never been higher. The so-called “8am rush” for GP appointments has featured prominently in the press over the last year.

337

Calver T, ‘Is this the end of the full-time family doctor?’, The Times, 22 July 2022, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/is-this-the-end-of-the-full-time-family-doctor-tvffppcnm

,

338

Letters to the editor, ‘My son could have flown to Spain and seen a doctor sooner’: your experiences of the NHS in 2022’, The Telegraph, 22 December 2022, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/opinion/2022/12/22/son-could-have-flown-spain-seen-doctor-sooner-telegraph-readers/

Supporting the anecdotal evidence with data is harder. It is possible to observe the number of appointments that general practice delivers: this increased by 12.4% between 2019/20 and 2022/23, an average of 4.0% per year. But that amount is necessarily limited by general practice capacity. There is therefore an unobservable number of people who try and fail to book an appointment on any given day (though there is evidence that people are finding it harder to book appointments, more on which below).

Demographic changes appear to have increased demand on general practice. While the overall population in England grew by 0.6% per year on average between April 2013 and April 2023, the over-65 population grew at 1.1% per year – the same proportion as rise seen in the number of patients registered with GPs. 339 NHS Digital, ‘Patients Registered at a GP Practice’, 12 October 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/patients-registered-at-a-gp-practice

That older population often has more complex needs – and the proportion of people aged 75 and over with two or more long term conditions is also increasing. 340 Raymond A, Bazeer N, Barclay C and others, Our ageing population, The Health Foundation, December 2021, p.20, https://www.health.org.uk/publications/our-ageing-population We heard throughout our interviews that patients are presenting with more complex conditions and therefore higher need for care across all health and social care services. This has again proved difficult to evidence, but if true would imply that it is not only the quantity of demand that has changed, but also the complexity.

Respondents to the GP Patients Survey also show decreasing satisfaction on questions related to access.

341

https://gp-patient.co.uk/surveysandreports

For example, the proportion of people who are satisfied with the experience of making an appointment and who found it easy to talk to someone on the phone dropped to 54.4% and 49.8% respectively in 2023, both the lowest scores on record. This has fed through to the lowest patient satisfaction on record with 71.3% reporting a positive experience of general practice in 2023, down from 82.9% in 2019. It could be argued that these results show a general frustration with the service. But polling shows that those who access the general practice are more satisfied with the service than those who do not.

342

Morris J, Schlepper L, Dayan M and others, Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2022, The King’s Fund, March 2023, figure 21, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/public-satisfaction-nhs-and-social-care-2022

These results imply that people are struggling to access general practice when they need to.

The proportion of people who had contact with general practice also declined in 2022, from 86% in 2021 to 84%.

351

Morris J, Schlepper L, Dayan M and others, Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2022, The King’s Fund, March 2023, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/public-satisfaction-nhs-and-social-care-2022

This could be because of falling demand, but could also be because well-publicised difficulties accessing general practice meant that people chose to stay away with conditions that they might previously have come forward for.

352

Institute for Government interviews

This doesn’t necessarily imply that GP workloads have fallen, however; a patient with increasingly high needs would demand more from general practice.

There are other reasons why demand could in fact be rising in general practice. The phenomenon of “workload dumping” from secondary care into primary care – the inappropriate transfer of work from hospitals to GPs – has been recognised for a while as a driver in demand for GP services, 353 Baird B, Charles A, Honeyman M and others, Understanding pressures in general practice, The King’s Fund, May 2016, p.52, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/Understanding-GP-pressures-Kings-Fund-May-2016.pdf though it is difficult to know if this has worsened in recent years.

All of these measures of demand are incomplete and it is difficult to unpick how much of the demand from the past few years was part of a pandemic backlog that may now largely have been cleared. Either way, it is clear that there is more demand for GP services than general practice can meet.

The government is attempting to manage demand out of the system

The government has recognised that demand pressures are a problem. It used NHS England’s Delivery Plan for Recovery Access to Primary Care 354 NHS England, ‘Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care’, 9 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/delivery-plan-for-recovering-access-to-primary-care-2/ to implement various measures to improve access to GP services, which can involve directing patients to where they might be able to access more appropriate care. These include:

- improved patient self-referral to hospital care

- self-treatment

- use of other practice staff to meet demand

- rollout of “care navigation” and to better advise and signpost patients to the right service or health professional

The Delivery Plan claims that practice teams spend 10%-20% of their time on “lower-value administrative work and work generated by issues at the primary-secondary care interface”.

355

NHS England, ‘Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care’, 9 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/delivery-plan-for-recovering-access-to-primary-care-2/

The NHS plans to alleviate some of that pressure using measures such as encouraging secondary care colleagues to make onward referrals within secondary care, rather than returning the patient to primary care for the referral to be made.

356

NHS England, ‘Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care’, 9 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/delivery-plan-for-recovering-access-to-primary-care-2/

It is still too soon, however, to assess if these will be effective. The NHS frames these interventions as signposting patients to a more appropriate service, thereby reducing demand for general practice. This could work – as long as there is sufficient capacity in those other services. It could be more appropriate, for example, for a patient to receive care from community health services. But there is evidence that capacity in community health has declined,

357

Scobie S and Kumpunen S, ‘The state of community health services in England’, blog, Nuffield Trust, 10 February 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/the-state-of-community-health-services-in-england-0-0

with a 34.1% and 30.3% decline in the number of district nurses and health visitors respectively between September 2010 and June 2022.

358

Scobie S and Kumpunen S, ‘The state of community health services in England’, blog, Nuffield Trust, 10 February 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/the-state-of-community-health-services-in-england-0-0

Workforce

The number of fully-qualified, permanent GPs continues to fall

Continuing a long-running trend, the number of fully qualified, permanent GPs fell again in 2022/23, with 372 fewer in March 2023 than in the same month the year before – a 1.4% decline. This means the number is 6.7% (1,924 total GPs) lower in March 2023 than in September 2015.

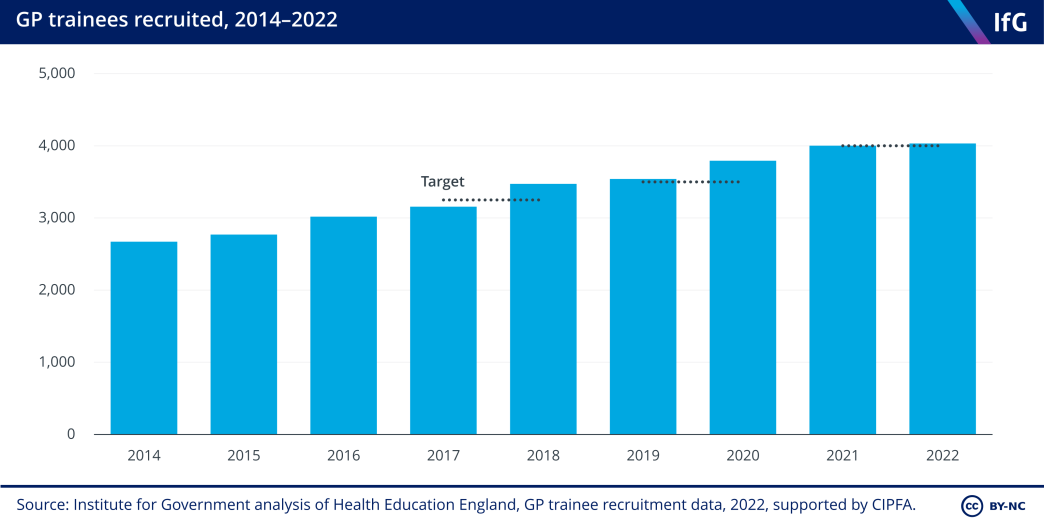

The NHS recruited a record number of GP trainees in 2022

While the number of fully qualified, permanent GPs has declined, the NHS recruited a record 4,032 GP trainees in 2022 – the fifth year in a row that it has exceeded its recruitment target. The NHS has plans to further increase the number of GP trainees, with an ambition to have 6,000 trainees by 2031 – a 50% increase in the current number of training places.

However these record numbers of trainees are not translating into an increase in full time-equivalent (FTE) GPs. This is for a few reasons. Interviewees claimed that the realities of working as a GP often put trainees off continuing with the specialty. Many of the same factors that lead more experienced GPs to leave the service also act as push factors for trainee (and newly qualified) GPs. In particular, high workloads, long hours and stressful working conditions mean that many trainees look elsewhere for work when they qualify, and often move specialties; some choose to work abroad. 361 Powell J, Gorsia M, Wood M and others, ‘Understanding doctors’ decisions to migrate from the UK’, General Medical Council, 18 October 2022, p.38, https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/migration-decisions-research-report_pdf-94525731.pdf

While it is good that the NHS is managing to recruit more GP trainees than ever, it is not without cost. Training is undertaken by senior colleagues, known as GP trainers, who supervise trainees until they are confident that they are competent enough to work alone.

362

Health Education England, ‘The GP Trainer's role includes two main activities - Educational Supervisor and Clinical Supervisor’, 21 May 2021, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.westmidlandsdeanery.nhs.uk/gp/trainers/role-of-the-gp-trainer

More trainees means more training. That increases the workload of other GPs. At a time when GPs are already leaving general practice due to poor work life balance, this risks further worsening the retention problem.

The NHS is increasingly relying on international recruitment to fill trainee roles

It is not just the number of GP trainees that has changed in recent years, but also the source of GP trainees. There were 4,443 more GP trainees in September 2022 than in September 2015. But the increase has been predominantly driven by recruitment from abroad, with 3,568 more trainees from outside the UK and the European Economic Area – a 519.0% increase in that time. In contrast, the number of UK trainees increased by only 46.1% (or 1,674) over the same period. Trainees from the rest of the world made up 40.8% of the total number in June 2023 compared to 17.0% in June 2018, before the recent recruitment drive.

This increasing reliance on international medical graduates (IMGs) to fill GP training spots raises questions of sustainability, ethics and value for money. On sustainability, the UK faces increasing competition from the rest of the world for a limited pool of medical graduates. Recruiting doctors away from other, often more deprived, countries falls into an ethical grey area.

On value for money, the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) estimates that it costs the NHS £50,000 per trainee per year, regardless of country of origin.

365

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Fit for the future: Opening the door to international GPs’, RCGP.ORG.UK, 2023, p.2, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/7747a58e-bb5a-423e-ad25-5af9e0f0e90f/opening-door-international-gps.pdf

But work from the General Medical Council (GMC) shows that IMGs are more likely to leave the NHS sooner than UK trainees. Some 89% of UK graduates who registered with the GMC in 2015 were still licensed in 2021, compared to 66% of IMGs.

366

General Medical Council, ‘The state of medical education and practice in the UK, 2022’, October 2022, p.58 https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/workforce-report-2022---full-report_pdf-94540077.pdf

This implies that the government is getting less for the money it invests in IMGs than British graduates.

Younger GPs are leaving general practice at record rates

As with other public services, there was a drop in people leaving general practice during the pandemic, followed by an increase in the immediate aftermath. In the 12 months to March 2023, some 8.8% of GPs (by full-time equivalent) left the service – above the low of 6.7% in the 12-months ending June 2021, but not out of line with pre-pandemic levels. However, a quarter of GPs under 30 (24.3%) and one in ten GPs aged between 30 and 39 (10.2%) left general practice over this period – a record for the latter age group.

When leaving rates rise (Figure 8) the number of GPs in those age groups will fall unless recruitment increases. Figure 9 shows that poor retention of young GPs has resulted in the number of fully-qualified, permanent GPs under the age of 40 falling at the fastest rate of any age bracket, with 912 fewer GPs in that group in March 2023 than in March 2016 – an 11.4% decline. In comparison, the overall number of fully qualified permanent GPs declined by 7.0% in the same period. This raises questions about the sustainability of the GP workforce.

The number and proportion of GP partners Is at its lowest on record

Declining overall numbers of GPs hides a more nuanced picture when it comes to the split between GP partners and salaried GPs. There were 4,923 fewer GP in March 2023 than in March 2016, a fall of 22.9%. In comparison, the number of salaried GPs increased by 2,728 (or 38.5%) over the same period. In March 2023, GP partners accounted for 62.3% of fully-qualified, permanent GPs, compared to 75.0% in March 2016.

There are several reasons why the number of GP partners is declining. First, in common with salaried GPs, trainees and the wider general practice workforce, many partners have experienced high workloads and burnout during and after the pandemic. But, if anything, this story is more severe for GP partners. Many partners might say that they are not only clinicians but also effectively small business owners who manage budgets, employ staff, and lease and maintain premises – all factors which increase stress and burnout.

In particular, the financial burden of partnership deters potential partners. That is both in terms of the initial amount to buy into a partnership (for example, by potentially purchasing a portion of the practice premises

377

BMJ Careers, ‘BMJ Careers: Guide To GP Partnerships’, BMJ.COM, 11 August 2022, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.bmj.com/careers/article/the-bmj-s-guide-to-gp-partnerships

), but also in terms of the liability that an individual takes on. Most GP partnerships operate as “unlimited liability partnerships”,

378

Department of Health and Social Care, ‘GP Partnership Review’, January 2019, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/770916/gp-partnership-review-final-report.pdf

meaning that a partner is liable for any and all costs associated with the partnership. This also brings with it the risk of being the “last partner standing”, wherein every other partner resigns or retires and the practice is unable to recruit any new partners, leaving the final partner with all financial liability.

379

Department of Health and Social Care, ‘GP Partnership Review’, January 2019, p.17, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/770916/gp-partnership-review-final-report.pdf

This creates a potentially vicious feedback loop: as the number of GP partners declines, the financial liability for the remaining GP partners increases, making the prospect of becoming a GP partner less attractive.

There are some solutions that could work to alleviate these disincentives. There is not necessarily a good reason why the partnership model has to operate as predominantly unlimited liability partnerships and one relatively low cost reform the government could introduce would be to allow for other legal structures – such as limited liability partnerships or companies – to hold the full range of GP contracts.

380

Department of Health and Social Care, ‘GP Partnership Review’, January 2019, p.17, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/770916/gp-partnership-review-final-report.pdf

[1] This is a proposal that the new chair of the BMA’s GPC for England, Dr Katie Bramall-Stainer, has indicated she would like to explore in the negotiation of the next GP contract,

381

GP Online, ‘Podcast interview: Dr Katie Bramall-Stainer, BMA GP committee for England chair’, podcast, GPonline.co.uk, 11 August 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gponline.com/podcast-interview-dr-katie-bramall-stainer-bma-gp-committee-england-chair/article/1832999

and which the health and social care select committee recommended in its report The future of general practice.

382

House of Commons Committee of Health and Social Care, The future of general practice: Fourth report of the session 2022-23 (HC 115), The Stationery Office, p. 38, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/30383/documents/176291/default/

The issue of premises is more complex. In Scotland the government recognised that upfront cost of entering a partnership and the liability associated with premises ownership was deterring GPs from becoming partners.

383

Scottish Government, ‘The national code of practice for GP premises’, November 2017, p.4, https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/advice-and-guidance/2017/11/national-code-practice-gp-premises/documents/0052753…

In response, it is introducing a scheme that will, in the first instance, allow GPs to take out interest free loans from the government to release equity on their premises before the government eventually purchases the entire primary care estate by 2043.

384

Scottish Government, ‘The national code of practice for GP premises’, November 2017, p.12, https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/advice-and-guidance/2017/11/national-code-practice-gp-premises/documents/0052753…

This would likely help promote partnership in England (and would also have the unintended benefit of giving the NHS greater control over the primary care estate, as discussed above) but would be very costly for the government – in 2019, the NHS estimated that it would cost “a minimum of £5-£6bn” to buy out the GP owned estate.

385

NHS England and Improvement, ‘General Practice Premises Policy Review’, June 2019, p.10, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/general-practice-premises-policy-review.pdf

The Department for Health and Social Care’s entire capital budget for 2023/24 is £10.4bn.

386

HM Treasury, Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021: A stronger economy for the British people, HC 822, The Stationery Office, October 2021, p.186, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1043689/Budget_AB2021_Web_Accessible.pdf

The result of these disincentives to enter partnerships is that the number of young GP partners has dropped substantially. In March 2023, there were 2,208 GP partners under the age of 40, down from 4,041 in March 2016 – a decline of 45.4%. This is far a steeper drop than the fall in the number of GP partners overall which fell 22.9% in that time and also a greater decline than the overall number of GPs under the age of 40 which fell by 11.4% in the same time.

It is not just that there are fewer young GPs and therefore fewer young GP partners; among those GPs who remain in general practice, younger GPs are opting to stay in salaried positions at a far greater rate than they did in 2016. In March 2016, the proportion of GPs that were aged 35-39 and were partners was 62.2%. By March 2023, this had fallen to 39.2% – a 23 percentage point decline. In comparison, there was only a 6.8 percentage point decline among GPs aged over 65.

The decline in GP partners is likely contributing to the trend of more practices closing.

403

British Medical Association, ‘Pressures in general practice data analysis’, BMA.ORG.UK, 28 September 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/pressures/pressures-in-general-practice-data-analysis

In response to a recent RCGP survey, two thirds of staff (65%) who said that their practice was at risk of closing claimed that it was due to GP partners leaving.

404

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Fit for the future: GP pressures 2023’, RCGP.ORG.UK, March 2023, p.8, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/f16447b1-699c-4420-8ebe-0239a978c179/gp-pressures-2023.pdf

The decline in the number of GP partners also has a more intangible impact; due to their financial investment, they have a strong incentive to make sure the practice is a success. This manifests as partners undertaking more work on average than their salaried colleagues

405

Odebiyi B, Walker B, Gibson J, Sutton M, Spooner S and Checkland K, Eleventh National GP Worklife Survey, PRUComm, 13 April 2022, p. 21, https://prucomm.ac.uk/assets/uploads/Eleventh%20GPWLS%202021.pdf

– or ‘discretionary effort’, a resource which interviewees told us is invaluable to the functioning of general practice.

406

Institute for Government interview

Declining numbers of GP partners could mean less of this resource.

On the face of it, the shift towards more salaried GPs – particularly among the younger generation – poses risks to the continuation of the GP partnership model. This could lead to increased calls for a change to the model – a potential route that both the Conservatives

407

PA Media, ‘Sajid Javid calls for patients to pay for GP and A&E visits’, The Guardian, 20 January 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/jan/20/sajid-javid-calls-for-patients-to-pay-for-gp-and-ae-visits

and Labour

408

Taylor H, ‘Labour ‘would tear up contract with GPs’ and make them salaried NHS staff', The Guardian, 7 January 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jan/07/labour-would-tear-up-contract-with-gps-and-make-them-salaried-nhs-staff

have mooted. But it should be stressed that the partnership model is far from doomed; interviewees told us that many of the pressures on GP partners could be alleviated with concerted efforts to remove additional workload and financial pressures from GP partners.

409

Institute for Government interview

High GP workloads are contributing to greater stress and burnout

According to interviews and surveys of GPs, the factor that contributes to both declining FTE GP numbers and worsening retention rates among younger GPs more than any other is high workloads, which leads to greater stress and burnout. The most recent GP work-life survey (which only shows results from a survey conducted in 2021 and is commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research) shows that increasing workloads and increased demand from patients are the two greatest contributors to stress in the job. 410 Odebiyi B, Walker B, Gibson J, Sutton M, Spooner S and Checkland K, Eleventh National GP Worklife Survey, PRUComm, 13 April 2022, p. 15, https://prucomm.ac.uk/assets/uploads/Eleventh%20GPWLS%202021.pdf

It is difficult to accurately capture the number of hours that GPs work per week. Data published by NHS Digital shows that 77% of fully qualified, permanent GPs worked less than 37.5 hours per week in March 2023, compared to 66.7% in September 2015.

411

https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-and-personal-medical-services/30-april-2023

This would appear to indicate that GPs are working less than in the past. But the story is more complex than that. GPs’ work often extends outside of their official “working hours”, as they are required to catch up on administrative work that they could not complete while they were seeing patients.

412

Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘GP working hours more complex’, press release, 21 November 2021, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/News/GP-working-hours-more-complex

This is so prevalent that many GPs make a formal move to part-time work so that they can work somewhere near to the typical 37.5 hours per week that a full-time GP is supposed to work.

The UK is also an international outlier in terms of GP workloads. GPs in the UK have the lowest level of job satisfaction among comparable countries

413

Beech J, Fraser C, Gardner T and others, Stressed and overworked, The Health Foundation, March 2023, https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/stressed-and-overworked

and report the highest levels of stress.

414

Beech J, Fraser C, Gardner T and others, Stressed and overworked, The Health Foundation, March 2023, https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/stressed-and-overworked

,

415

Odebiyi B, Walker B, Gibson J, Sutton M, Spooner S and Checkland K, Eleventh National GP Worklife Survey, PRUComm, 13 April 2022, https://prucomm.ac.uk/assets/uploads/Eleventh%20GPWLS%202021.pdf

Primary care networks and direct primary care staff

The government hit its manifesto commitment target for DPC staff a year early

In 2019, the Conservative Party promised to recruit 26,000 more DPC staff by March 2024.

416

The Conservative and Unionist Party, The Conservative and Unionist Party Manifesto 2019, 24 November 2019, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.conservatives.com/our-plan/conservative-party-manifesto-2019

They did this by providing additional funding through the Additional Role Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS), with the goals of “expanding general practice capacity… improv[ing] access for patients, support[ing] the delivery of new services and widen[ing] the range of offers available in primary care”.

417

NHS England, ‘Expanding our workforce’, ENGLAND.NHS.UK, [no date], retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/expanding-our-workforce/

The government hit its target in March 2023 – a year ahead of schedule.

418

Department of Health and Social Care, ‘Government meets target one year early to recruit primary care staff’, press release, 18 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-meet-target-1-year-early-to-recruit-primary-care-staff

The increase in DPC staff is not spread evenly across all staff groups. Of the additional 31,370 staff recruited between March 2019 and June 2023, more than half (55.5%) were accounted for by four staff groups: pharmacists, care coordinators, social prescribing link workers, and pharmacy technicians. The NHS intends that the largest of those staff groups – pharmacists – independently prescribe/re-prescribe medication and provide medication advice to other healthcare professionals, among other roles. 429 NHS England, ‘Additional roles: A quick reference summary’, ENGLAND.NHS.UK, 16 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/additional-roles-a-quick-reference-summary/

The full effects of this recruitment drive are unclear

The NHS publishes data on the total number of ARRS staff employed in PCNs, but told us that it does not collect data for the number of appointments carried out by all staff groups, meaning that it is impossible for either us or the NHS to effectively evaluate the efficacy of this recruitment drive. 430 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/appointments-in-general-practice It does though seem that the new staff are expanding the types of services offered to patients in primary care with, for example, more physiotherapists and paramedics than before 2019. This is undoubtedly of benefit to patients.

But it is also unclear what effect the large increase in staff is having on GP workload. Evidence shows that new staff struggled to properly embed in general practice, with a lack of clarity around the roles that many of them would play. 431 Baird B, Lamming L, Bhatt R and others, Integrating additional roles into primary care networks, The King’s Fund, February 2022, p.9, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-02/Integrating%20additional%20roles%20in%20general%20practice%20report%28web%29.pdf , p.9 Even when those new employees have been integrated into PCNs they still require extensive management by GPs. 432 Institute for Government interview And while the goal of hiring additional staff was to free up GP time, this is not always the case. Interviewees told us that DPC staff generally carry out tasks that GPs do not typically do themselves (for example social prescribing) rather than ones they do, making it difficult for GPs to shift their own work across to them. 433 Institute for Government interview In some cases they do take work from GPs and the NHS, rightly, told us that it is more appropriate for physios to treat bad backs and for healthcare assistants to do blood tests than GPs. 434 NHS England correspondence with the IfG But in these cases, DPC staff often take on the simpler cases, leaving GPs with the more complex – and therefore more time consuming and stressful – work. 435 Baird B, Lamming L, Bhatt R and others, Integrating additional roles into primary care networks, The King’s Fund, February 2022, p.18, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-02/Integrating%20additional%20roles%20in%20general%20practice%20report%28web%29.pdf

The large surge in recruitment has meant that PCNs often end up competing with other parts of the health and care sector for DPC staff. This has been most apparent in the recruitment of pharmacists; as the number of ARRS pharmacists has increased, there has been a worsening workforce crisis in community pharmacy. 436 Pym H and Wright N, ‘Scores of local pharmacies closing across England’, BBC, 8 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-65481473

Despite these remaining challenges, the success of the ARRS scheme should not be understated. Interviewees stressed the importance of DPC staff in recent years, with one interviewee saying “it’s hard to think where we’d be without [the additional DPC staff], because of the decline in GP numbers”.

437

Institute for Government interview

But there is still a way to go before they reach full effectiveness.

Activity

General practice is doing more with less

Despite the noted fall in fully-qualified, permanent GPs, the number of appointments that GPs delivered reached a record level in 2022/23 – with GPs providing 162.3m appointments, 0.2% more than in 2021/22 and 5.3% more than in 2019/20. Interestingly, this is in contrast to secondary care, where on some measures there is less activity than in 2019/20, despite higher staffing numbers. 438 Freedman S and Wolf R, The NHS productivity puzzle, Institute for Government and Public First, June 2023, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/nhs-productivity

Other practice staff are also delivering record numbers of appointments, with 163.3m provided in 2022/23 – an increase of 11.6% compared to 2021/22 and 19.5% compared to 2019/20. This is a far greater increase than the number of GP appointments because of the increase in DPC staff.

Given changing staffing levels, a better metric of activity might be the number of appointments delivered per FTE staff member. According to this metric, both GPs and other practice staff have increased the number of appointments delivered per FTE, with GPs (excluding trainees) delivering 8.3% more appointments per FTE in the 12 months to March 2023 than in the 12 months to September 2019[1] and other practice staff[2] providing 6.3% more.

Remote appointments are falling, but remain above pre-pandemic levels

The way GPs deliver appointments has not returned to pre-pandemic behaviours. In 2022/23, some 29.1% of appointments were delivered by telephone or online compared to 15.2% in 2019/20. But there has been a steady move back towards more in-person appointments since the height of the pandemic: in 2020/21, two fifths of appointments were delivered by telephone or online (42.0%).

The persistently high level of remote GP appointments – despite NHS guidance that practices should “ensure they are offering face to face appointments” 443 NHS England, ‘UPDATED STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE (SOP) TO SUPPORT RESTORATION OF GENERAL PRACTICE SERVICES’, ENGLAND.NHS.UK, 13 May 2021, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/B0497-GP-access-letter-May-2021-FINAL.pdf – may be because telephone appointments are popular with the public. Data from AskmyGP, a company which provides triage tools and software to GPs, shows that patients request telephone consultations more frequently than they are given them. 444 Longman H, ‘Who chooses how a patient sees their GP?’, blog, Ask My GP, 5 November 2021, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://askmygp.uk/category/evidence/

The UK seems to be an outlier in terms of mode of appointment, delivering by far the greatest proportion of its appointments remotely compared to other countries. 445 Beech J, Fraser C, Gardner T and others, Stressed and overworked, The Health Foundation, March 2023, p.18, https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/stressed-and-overworked There is a potential explanation in that survey – GPs in the UK are also the most likely to think that remote appointments can offer “timely and appropriate care”. 446 Beech J, Fraser C, Gardner T and others, Stressed and overworked, The Health Foundation, March 2023, p.19, https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/stressed-and-overworked

GPs are still referring people less frequently

The rate at which GPs refer patients fell in the first months of the pandemic as GPs attempted to keep patients away from hospitals. The proportion of GP appointments that result in a referral has increased steadily since the height of the pandemic and reached 8.6% in 2022/23, up from 8.1% in 2021/22 – though this is still lower than the 9.2% of attended GP appointments which resulted in a referral in 2019/20.

This reduction is due in part to continued use by GPs of Advice and Guidance (A&G) – a mechanism by which GPs consult with secondary care colleagues about whether or not they should refer a patient before making a referral. The goal of this policy is to reduce the number of unnecessary referrals from primary to secondary care, thereby lowering the number of people on the elective waiting list 450 NHS England, ‘Advice and Guidance’, ENGLAND.NHS.UK, [no date], retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/elective-care-transformation/best-practice-solutions/advice-and-guidance/ and improving outcomes for patients.

Since it was introduced in 2019, the number of requests for A&G has risen from approximately 40,000 per month to more than 160,000 in March 2023 – a 300% increase. NHS guidance for 2022/23 set general practice the target of using “specialist advice requests” (which includes A&G) for 16 of every 100 first outpatient attendances. 451 NHS England, ‘2022/23 priorities and operational planning guidance’, ENGLAND.NHS.UK, 22 February 2022, retrieved 18 October 2023, p.14, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/20211223-B1160-2022-23-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance-v3.2.pdf The National Audit Office (NAO) found that general practice has far exceeded that target, with GPs seeking A&G in 22 of 100 first outpatient appointments. 452 Comptroller and Auditor General, Managing NHS backlogs and waiting times in England, Session 2022-23, HC 799, National Audit Office, 2022, p.9, https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/managing-NHS-backlogs-and-waiting-times-in-England-Report.pdf

A&G is not just about managing demand out of the system and protecting hospitals from rising demand; there are also benefits for both GPs and patients. For patients, it means they avoid having to wait months or years on an elective waiting list unnecessarily. Interviewees also told us that GPs will almost always refer a patient if they insist on it, meaning that A&G rarely overrides patient wishes. Some GPs like A&G because they feel supported when deciding whether or not to refer a patient 462 Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Advice and guidance’, RCGP.ORG.UK, May 2022, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/representing-you/policy-areas/advice-and-guidance – a decision which is often quite stressful, particularly in the context of increasing workloads. 463 Riley R, Spier J, Buszewicz and others, ‘What are the sources of stress and distress for general practitioners working in England? A qualitative study’, BMJ Open, 2018, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/1/e017361

Despite this, there are still unanswered questions about what happens to those that end up on A&G pathways. If their condition worsens following a non-referral, they may present again to their GP with the same complaint. Or they may require care elsewhere, for example in the adult social care sector. An RCGP survey showed that 64% of GPs surveyed believed A&G was being used to reduce the elective backlog in secondary care. 464 Royal College of General Practitioners, ‘Advice and guidance’, RCGP.ORG.UK, May 2022, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.rcgp.org.uk/representing-you/policy-areas/advice-and-guidance Even if this route is beneficial to the majority of patients and to the health service, more work needs to be done to understand potential unintended consequences for patients and for the health and care system.

Access

The number of practices continues to decline

There were approximately 6,400 GP practices open in March 2023, down from just over 8,000 in April 2014 – a decline of 20%. 465 Bostock N, ‘Fifth of GP practices have closed or merged since NHS England was formed’, GP Online, 20 June 2022, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gponline.com/fifth-gp-practices-closed-merged-nhs-england-formed/article/1790429 There is no data for what happens to practices that were previously open, but evidence suggests that the majority is due to the merging and takeover of practices, rather than outright closures (some larger practices have multiple sites, but it is impossible to tell from the available data what has happened to the total number of GP sites). 466 British Medical Association, ‘Pressures in general practice data analysis’, BMA.ORG.UK, 28 September 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/pressures/pressures-in-general-practice-data-analysis

Declining numbers of GP practices mean that patient list sizes have been increasing over the last decade. This means that practices can often find economies of scale. Work from Nuffield Trust says that a “10% increase in patient list size is associated with a 3% reduction in cost per patient”, 467 Palmer B, Appleby J and Spencer J, Rural health care, Nuffield Trust, January 2019, p.3, https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-01/rural-health-care-report-web3.pdf implying that practices with larger list sizes could offer better value for money.

The evidence for patient experience in practices of different sizes is more mixed. Work by the IFS shows that larger practices achieved the highest Quality Outcome Framework (an NHS programme designed to incentivise improved patient outcomes

468

NHS England, ‘QOF 2022-23 results’, DIGITAL.NHS.UK, [no date], retrieved 18 October 2023, https://qof.digital.nhs.uk/

) scores and single-handed practices – by definition the smallest – achieved the lowest.

469

Stoye G, ‘Does GP Practice Size Matter? The relationship between GP practice size and the quality of health care’, blog, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 20 November 2014, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://ifs.org.uk/articles/does-gp-practice-size-matter-relationship-between-gp-practice-size-and-quality-health-care

The same paper, however, also says that “patients appear to be more satisfied with the care received in small practices, despite objective measures suggesting that they receive worse clinical standards of care”.

470

Stoye G, ‘Does GP Practice Size Matter? The relationship between GP practice size and the quality of health care’, blog, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 20 November 2014, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://ifs.org.uk/articles/does-gp-practice-size-matter-relationship-between-gp-practice-size-and-quality-health-care

Patient to GP ratios are increasing, and are worse in more deprived parts of the country

At the same time that the number of GPs has been falling, the number of patients registered with practices has increased. The number of patients per GP has risen from 1,990 in September 2015 to 2,340 in March 2023 – an 11.8% increase.

There is, however, no ratio of patients to GPs that is universally accepted as “safe” and the NHS does not provide an opinion on what it deems to be a safe level. Despite this, some argue that patient to GP levels have increased too far. One estimate by a local medical committee (LMC) put the safe ratio of patients to fully-qualified, permanent GP at 1,800. 474 [1] Bostock N, ‘1 in 5 people in England would be without a GP if practices stuck to 'safe limit'’, GP Online, 18 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.gponline.com/1-5-people-england-without-gp-practices-stuck-safe-limit/article/1823054 In March 2023, the patient to GP ratio was 2,340 across England, 30.0% above 1,800. The Health and Social Care select committee also recommended returning to personal lists for GPs, to improve continuity of care, and limiting list sizes to 2,500, with the aim of reaching 1,850 over five years. 475 House of Commons Committee of Health and Social Care, The future of general practice: Fourth report of the session 2022-23 (HC 115), The Stationery Office, p. 28, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/30383/documents/176291/default/ This would require the NHS to employ 7,300 more fully-qualified, permanent FTE GPs – 27.7% more than at present. The government rejected this recommendation in its response to the committee’s report. 476 House of Commons Committee of Health and Social Care, The future of general practice: Government Response to the Committee’s Fourth Report: Ninth special report of the session 2022-23 (HC 1751), The Stationery Office, p. 16, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/41014/documents/199705/default/

Across England, only a quarter of GP practices had patient-GP ratios less than or equal to 1,800 (24.9%) and 7.8% had ratios of more than 5,000. The increase in the ratio of patients to GP has also been greater in more deprived areas of the country. GP practices in the most deprived decile of the country saw patient to GP ratios rise form 2,073 in 2016 to 2,568 in 2023 – a 23.9% increase. In contrast, the ratio increased from 2,019 in 2016 to 2,180 in 2023 in the least deprived decile, a comparatively small increase of only 8.0%. This has resulted in the most deprived decile of the country having a patient-GP ratio that is 8.7% higher than the least deprived decile in March 2023. In March 2016, it was only 3.1% higher.

NHS England has recognised this and is actively trying to recruit more GPs to the most underserved parts of the country through the Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme. 485 NHS England, ‘Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme’, ENGLAND.NHS.UK, [no date], retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/the-best-place-to-work/starting-your-career/recruitment/

Larger patient lists for each GP inevitably means that GPs will be under more pressure to see more patients. The BMA recommends that GPs do not have more than 25 “patient contacts” per day. 486 British Medical Association, ‘Safe working in general practice, BMA.ORG.UK, 11 August 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/gp-practices/managing-workload/safe-working-in-general-practice This is likewise not a perfect metric of safe working levels as a “patient contact” can be interpreted in a number of ways and can vary substantially in length. Putting aside concerns about the measure, a report from Policy Exchange in 2022 estimated that GP contacts exceed 37 per day. 487 Philps S, Ede R and Landau D, At your service, Policy Exchange, March 2022, p.31, https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/At-Your-Service.pdf The rising workload for GPs led The Health and Social Care committee to concluded in their report The Future of General Practice that “patients are facing unacceptably poor access to, and experiences of, general practice and patient safety is at risk from unsustainable pressures”. 488 House of Commons Committee of Health and Social Care, The future of general practice: Fourth report of the session 2022-23 (HC 115), The Stationery Office, p. 12, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/30383/documents/176291/default/

The government’s access plan only helps at the margins

The Sunak government’s Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care seeks to address this. 489 NHS England, ‘Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care’, 9 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/delivery-plan-for-recovering-access-to-primary-care-2/ As the IfG has previously argued, 490 Hoddinott S, ‘The government’s plans for general practice will do little to improve patient access’, blog, Institute for Government, 10 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/general-practice-patient-access the measures announced in the plan may improve patients’ experience of phoning practices and booking appointments, but are unlikely to meaningfully improve access. Similarly, shifting work to pharmacists will help free up GP time in the short run, but extra capacity is likely to be consumed by demographic demand pressures in the next few years. 491 Hoddinott S, ‘The government’s plans for general practice will do little to improve patient access’, blog, Institute for Government, 10 May 2023, retrieved 18 October 2023, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/general-practice-patient-access

Improving GP access will require investment in general practice. Part of that investment would need to be in the workforce. The recruitment of DPC staff has been successful, as discussed above, but some elements of the service can only be provided by GPs. The NHS has plans to recruit more GPs as part of the Long Term Workforce Plan, but this chapter has shown that a large expansion in GP trainee numbers does not necessarily translate into rising numbers of GPs. The plan also does not give any clear indication of the number of GPs that it expects those additional GP trainees to convert into, making it difficult to evaluate the effect that the plan will have on the workforce and, therefore, general practice capacity.

The chapter has also shown that the estate is also not in a fit state for a large expansion of the workforce. The successful addition by the NHS of more than 26,000 DPC has not been met with a commensurate increase in the size or appropriateness of the estate. 492 Baird B, Lamming L, Bhatt R and others, Integrating additional roles into primary care networks, The King’s Fund, February 2022, p.16, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-02/Integrating%20additional%20roles%20in%20general%20practice%20report%28web%29.pdf Until the government solves these issues, it is unlikely that the supply of primary care will keep pace with demand.

- Topic

- Public services

- Department

- Department of Health and Social Care

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government