Performance Tracker 2023: Cross-service analysis

Public services are under considerable strain, with years of tight funding, staffing problems and underinvestment in capital all taking their toll.

Performance

Most public services are performing worse now than on the eve of the pandemic

Eight of the nine services covered in this report are performing worse now than they were in 2019/20. In many ways this is unsurprising. The pandemic was an unprecedented disruption to public service delivery and placed some major new demands on services – particularly health care – and it is to be expected that the backlogs and unmet needs that arose during this period would take some time to be addressed. But the depth of problems and speed of recovery have been worse than they might have been because of the state of public services when the pandemic hit.

Indeed, previous Institute for Government and CIPFA research

223

Guerin B, Atkins G, Davies N and Sodhi S, How fit were public services for coronavirus?, Institute for Government, 3 August 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/how-fit-were-public-services-coronavirus

found that of the services covered in this report, only schools were performing better than they were in 2010. The performance of all other services had fallen, with the biggest declines being seen in prisons, hospitals, general practice and adult social care. Neighbourhood services were not covered in that report, and the government lacks good performance data for most, but many of these services became harder to access in the 2010s, with fewer accessible bus routes outside London, less frequent waste collection and fewer libraries.

224

Atkins G and Hoddinott S, Neighbourhood services under strain, Institute for Government, May 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/neighbourhood-services-under-strain

While performance has worsened in most services since 2019/20, criminal courts and hospitals are in serious trouble. The crown court backlog is at a record high, reaching 64,709 in June 2023, compared to just 40,826 in March 2020. And the situation is even worse than the headline figure suggests. A disproportionate number of cases in the backlog are jury trials, which take much longer to process. Accounting for this greater complexity, the backlog is now equivalent to 89,937 cases.

As a result of the large backlog, the average wait from a case being listed to a trial being completed has risen to 168 days in 2022, up from 115 days in 2019. But the overall wait from offence to completion now exceeds a year – rising from 251 days to 379 days over the same period. In both cases, there has been a small improvement over the past year.

Hospital services are also struggling badly, with people suffering very long waits for treatment. On all major performance metrics, hospitals are doing substantially worse than they were in 2019/20. In 2022/23, just over half of those attending A&E were admitted, transferred or discharged within four hours (56.7%), compared to three quarters in 2019/20 (75.4%). This is against a long-standing target of 95%, and a new target from December 2022 of 76%. The elective waiting list also continues to grow, reaching 7.8 million in August 2023.

The picture in general practice is more nuanced. Productivity appears to have improved, with a record number of appointments being delivered despite a fall in the number of fully qualified, permanent GPs. Direct patient care staff (DPC)* such as pharmacists are also providing more appointments in a wider range of services than ever. Despite this, patients are finding it harder to access primary care services, with demand easily outstripping supply.

Those who need adult social care are struggling to access publicly funded services. Large injections of funding over the past year have helped to partially stabilise the adult social care market, but staffing problems and capacity are worse than they were before the pandemic: vacancy rates in 2022/23 sat at 9.9% – an improvement on the 10.6% of 2021/22, but still well above the 6.7% in 2019/20.

Virtually all the neighbourhood services covered in this report are doing somewhat worse now than on the eve of the pandemic. There are, for instance, higher levels of rough sleeping, a continued deterioration in road quality and lower rates of recycling.

In schools, attainment in reading at key stage 2 and English and maths at key stage 4 appears to have stayed relatively steady, despite the disruption to learning caused by the pandemic. However, there has been a decline in maths and writing skills at KS2 – and there is likely to have been deterioration in other KS4 subjects besides these core curriculum ones. There is also a growing gap in attainment between disadvantaged pupils and their better-off peers. Given pupils who completed assessments in 2023 may have benefited from up to two and a half years of tutoring under the National Tutoring Programme, these results raise questions about the effectiveness of this programme. Meanwhile, many pupils’ learning has been disrupted by a sharp increase in absence rates since the pandemic, with more than one in six primary school pupils (17.2%) and more than one in four secondary school pupils (28.3%) estimated to have been persistently absent in 2022-23.

In the police, the absolute number of charges fell by 13.5% between 2019/20 and 2021/22, despite the big increase in the number of officers.** Perhaps counterintuitively, the big influx of new recruits has, in fact, been a short-term drain on the productivity of forces due to the amount of supervision and support that they need. The number of charges increased by a minimum of 8.9% in 2022/23, likely reflecting new officers becoming more productive, but this is still 5.8% lower than in 2019/20. Public trust in the police is also substantially lower than before the pandemic, as a result of high-profile scandals in recent years.

In prisons, the picture is mixed. Starts and completions of accredited programmes*** in 2021/22 were down 59.9% and 64.6% respectively compared to 2019/20, meaning fewer inmates are able to set themselves up for better opportunities on release. While numbers climbed between 2020/21 and 2021/22, it is unclear whether this is indicative of the start of a long-term recovery, or simply a bounce back after the initial shock of the pandemic. Rates of assault – both on other prisoners and on staff – were much lower in 2022/23 than in 2019/20, having fallen dramatically due to the pandemic. However, rates have been increasing for the last two years. Self-harm has fallen among male prisoners – who account for 96% of the prison population – but has increased substantially among women, with incidents per individual increasing by 79.3% from an already high level between 2019/20 and 2022/23.

The common factor behind these trends is that prisoners are now spending more time locked in their cells than they were before the pandemic. While that has had a positive impact on some performance indicators, like violence rates, these statistics do not tell the whole story and the overall effect is negative, with prisons less able to undertake the rehabilitative activities that are critical to their purpose.

Children’s social care is the one service that is performing at broadly the same level as it was in 2019/20. The proportion of cases seen within 15 days of a s47 assessment**** improved from 78.8% then to 80.0% in 2021/22. However, the proportion of child protection plans that were reviewed within the required timescales has fallen from 91.5% to 89.3% over the same time period. Ofsted inspection results have marginally improved, but only 74 of 152 councils have been assessed since inspections resumed in 2021, making it hard to draw firm conclusions.

* This includes care co-ordinators, pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, social prescribing link workers and others.

** This figure excludes some charges from 2019/20, so the fall is actually understated.

*** Intervention programmes offered to offenders, which address issues such as offending, violence and substance misuse. A full list is available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/960097/Descriptions_of_Accredited_Programmes_-_Final_-_210209.pdf

**** Investigations carried out by local authorities to assess if there is a risk of significant harm to a child or children.

Public service performance problems are systemic

There are serious performance issues in each of the individual services covered in this report. But they also operate as part of wider systems, 235 CIPFA, ’Whole system approach volume 1’, (no date), retrieved 16 October 2023, www.cipfa.org/policy-and-guidance/reports/whole-system-approach-volume-1 with problems in one service feeding into others. Such interrelated difficulties are most obvious in the health and care, criminal justice and local government systems.

Delayed discharge from hospitals of people who no longer need medical attention hampers elective and emergency activity by making it more difficult to admit new patients. This is not just felt on wards: ambulances cannot hand over patients to A&E if the system becomes jammed; and GPs find more of their referrals to hospitals are rejected or that their patients must wait longer for an appointment following a referral. And while hospitals themselves are responsible for a substantial proportion of delays – for instance, as patients suffer long waits for prescriptions or discharge plans before they can leave – many are due to a lack of capacity in adult social care and community health provision. Often, there is nowhere else to go for people who are ready to leave hospital.

Patients spending longer in hospital beds also face greater risk of losing mobility and acquiring infections, increasing demand on other health and community services. Such people may find themselves back at their GP sooner – but with demand in general practice already outstripping supply, and many unable to book timely appointments or access other support, some will instead go straight to A&E, increasing pressure on hospitals.

Similar systemic problems can be seen in criminal justice. The government’s successful programme to increase the number of police officers by 20,000 (between 2019 and 2023) has started to feed through into more charges, in turn increasing demand on the criminal courts and, eventually, prisons. Neither has had (nor likely will have) the capacity to adequately cope with this. As a result of judge and barrister shortages, increased case complexity and declining guilty plea rates, productivity is declining in the crown court. Similarly, the growth in the prison population is expected to exceed building plans. This comes in a context in which both were already struggling to cope with demand, despite lower than anticipated case flow. The government is not on track to meet its already unambitious crown court backlog target and prisons are at bursting point, having recently been forced to rely on last-ditch population-control attempts like early releases and sentence suspensions. This comes on top of the service’s reliance on temporary and police cells (and even the possibility of renting cells overseas 236 Chalk A, address at the Conservative Party conference, 3 October 2023, retrieved 16 October 2023, www.conservatives.com/news/2023/cpc23-address-from-alex-chalk ) due to delays to the prison building and refurbishment programme.

The slow progress in tackling the crown court backlog has also contributed to a 51.4% increase between February 2020 and June 2023 in the number of prisoners held on remand awaiting trial, adding to overcrowding. This has made it even harder for prisons to safely return to pre-pandemic regimes, leaving many prisoners stuck in their cells for more than 20 hours a day, with, as noted, less access to training and education than before the pandemic. Reduced provision of rehabilitative activity will likely have a knock-on effect on reoffending, which will in turn place additional pressure on the criminal justice system. 237 Ministry of Justice, ‘HM Prison and Probation Service Offender qualities Annual Report 2021 to 2022’ ('Chapter 5 tables: Accredited programmes in custody’), 24 November 2022, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hm-prison-and-probation-service-offender-equalities-annual-report-2021-to-2022

In local government, councils are responsible for the delivery of a wide range of public services but have been forced to make difficult decisions in the face of reduced funding and increased demand. This is not a new problem: between 2009/10 and 2021/22, local government spending power fell by 10.2%, due to substantial cuts to the value of central government grants. 238 Atkins G and Hoddinott S, ‘Local government funding in England’, Institute for Government, 10 March 2020, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/local-government-funding-england

At the same time, demand for adult and children’s social care services has grown. Since 2015/16, the number of requests for adult social care support from new clients has increased by 22.1% for 18–64 year olds. Similarly, the number of children in care and children protection plans grew by 27.5% and 30.2% respectively between 2009/10 and 2021/22. 239 Department for Education, ‘Children looked after in England including adoption’, 13 July 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoptions/2022

Local authorities are subject to statutory duties requiring them to safeguard and protect vulnerable children and adults. As a result, they have had to maintain social care provision at the expense of other services. The exact balance of cuts has depended on local circumstances and political priorities, but overall spending on non- social care services fell by 30.6% in real terms between 2009/10 and 2021/22. 240 Atkins G and Hoddinott S, Neighbourhood services under strain, Institute for Government, May 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/neighbourhood-services-under-strain

There are also important interdependencies between health and care, criminal justice, local government and wider services. Extensive hospital waiting lists and difficulties accessing general practice have created backlogs in medical appointments for an ageing prison population, placing additional pressure on prison officers. Long waits for NHS assessments for autism and ADHD are a barrier to providing earlier formal support to pupils with special educational needs to save costs later. And cuts to local authority funded youth services have likely placed additional crime and non-crime demand on the police.

Many interviewees also emphasised the knock-on impact of limited access to publicly funded mental health services, with particular pressure placed on hospitals, police, schools and children’s social care.

Covid no longer appears to be a major, direct drag on public service performance

In the first year of the pandemic, Covid had an unprecedented impact on the performance on public services. Many paused activities completely, at least initially, while most others were forced to implement stringent social distancing requirements or deliver services remotely. In Performance Tracker 2022: Public services after two years of Covid, 241 Davies N, Hoddinott S, Fright M and others, Public services after two years of Covid, Institute for Government, 17 October 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/performance-tracker-2022-0 we reported that the direct impact of Covid was much reduced but still present in some cases and particularly hospitals, where enhanced infection control measures were a continued drag on productivity.

At the time of writing, the pandemic is no longer having a meaningful direct impact on the performance of public services covered in this report. Buildings have reopened, social distancing has been scrapped and the NHS is no longer taking onerous additional precautions to protect against Covid infections.

There are, however, lingering indirect effects, most notably on staff, whose absence rates have remained much higher than pre-pandemic. In prisons, the number of working days lost to sickness among main operational staff was a quarter above the 2019/20 level (24.3%), even if slightly down on the previous year. In hospitals the proportion of available staff days lost to illness increased from 4.46% in 2019/20, to 5.36% in both 2021/22 and 2022/23 – an increase of nearly 20% across the two years. 242 NHS Digital, 'NHS sickness absence rates, April 2022, Monthly Tables, Table 2' https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-sickness-absence-rates/april-2023-provisional-statistics In children’s social care, the sickness absence rate is lower, at 3.5% in 2022, but that is still the highest since 2017 and up on 2.9% in 2020 and 3.1% in 2019.

Historic underinvestment in capital has hit public services hard

Covid is no longer having a direct impact on services – but problems persist. This is because while the pandemic was a serious shock, it also exacerbated and magnified pre-existing problems – most importantly, the historic underinvestment in capital and difficulties with recruitment and retention.

Compared to other rich nations the UK is a low-investment nation. According to analysis by the Resolution Foundation, UK government investment* has averaged around 2.5% of GDP since the year 2000, just two thirds of the OECD average of 3.7%. Indeed, the UK has consistently invested less than the average since at least 1960. 243 Odamtten F and Smith J, Cutting the cuts: how the public sector can play its part in ending the UK’s low-investment rut, Resolution Foundation, March 2023, p. 12, https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Cutting_the_cuts.pdf Looking at health capital specifically, since 1970 there have only been two years when the UK spent more than the OECD average and in most it spent substantially less. 244 OECD, ’Gross fixed capital formation in the health care system’, (no date), retrieved 16 October 2023, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SHA_HK#

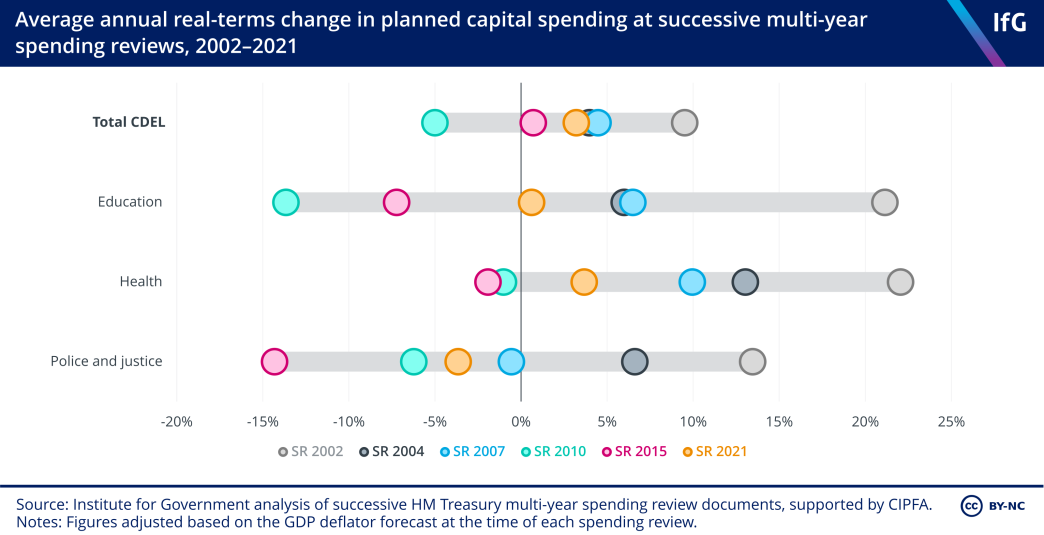

The pandemic came at a particularly bad time for the UK’s public sector. The decade before saw particularly deep cuts to the capital spending of the departments overseeing the services covered in this report. The worst hit was the MoJ, where annual capital spending averaged less than half the real-terms spending in 2007/08. Capital spending by DLUHC, HO and DfE all remain substantially below the levels of 2007/08. Even DHSC, which was relatively protected, saw cuts averaging around 8%. Capital spending by DHSC and MoJ grew substantially in 2020/21, but it will take time to undo the effects of historic low investment.

If the government had wanted to keep capital spending the same as the average between 2004/05 and 2007/08 for the whole of the 2010s for the departments covered in this report, it would have needed to spend an additional £24bn throughout that decade, in 2023/24 prices – about 12% more than the government actually spent in that time. But even that sum is equivalent to only around two thirds of the maintenance backlog across the services for which data is published (see below), reflecting that even between 2004/05 and 2007/08 capital spending was still not particularly generous.

In addition to receiving relatively ungenerous capital budgets, departments have consistently underspent, for a variety of reasons. Government suffers from persistent ‘optimism bias’ over how long projects will take to complete. There is insufficient capacity in the construction sector to deliver. And cuts to administrative budgets have reduced departments’ ability to spend quickly and well. 264 Atkins G, Tetlow G and Pope T, Capital spending: Why governments fail to meet their spending plans, Institute for Government, February 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/capital-investment-why-governments-fail-meet-their-spending-plans Some departments have used capital budgets to cover shortfalls in day-to-day spending: between 2014/15 and 2018/19, some £4.3bn of funding initially allocated to health capital was transferred in this way 265 Institute for Government analysis of Department of Health and Social Care, Department of Health and Social Care Annual Report and Accounts 2021–22, 26 January 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1135637/dhsc-annual-report-and-accounts-2021-2022_web… to meet “spending pressures”. 266 HM Treasury, Public Expenditure: Statistical analyses 2018, Cm9648, The Stationery Office, 2018, p.49, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b4f3e2240f0b61866427805/PESA_2018_Accessible.pdf

This has all had a serious impact on the productivity of public services, with problems with both the quality and quantity of capital assets. Teachers, nurses, doctors and social workers all find it harder to do their jobs in crumbling and cramped buildings, on old computers running out-of-date software, and without access to the latest equipment.

Sizeable maintenance backlogs have built up in some services. Across the hospitals, schools, criminal courts, prisons and the road network this now totals £37bn;**,

267

Department for Education, Condition of School Buildings Survey: Key findings, May 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/989912/Condition_of_School_Buildings_Survey_CDC1_-_ke…

,

268

House of Commons Justice Committee, ’Oral evidence: the work of the Ministry of Justice’, HC869, 1 March

2022, retrieved 17 October 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/9807/html

,

269

Figures provided by the Ministry of Justice.

,

270

NHS Digital, ’Estates Returns Information Collection, Summary page and dataset for ERIC 2021/22’, 13 October 2022, retrieved 17 October 2023, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/estates-returns-information-collection/england-2021-22

,

271

Asphalt Industry Alliance, Annual Local Authority Road Maintenance (ALARM) Survey, 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.asphaltuk.org/alarm-survey-page

in prisons, this has contributed to the shortage of cells and the need to make emergency use of police cells to hold inmates. Prisons are now so full that maintenance projects have been further delayed as governors cannot afford to move people out of substandard cells while they are repaired. In the NHS, almost a fifth of the record maintenance backlog is classified as ‘high risk’ (17.6%), which means repairs must be carried out urgently to avoid “catastrophic failure, major disruption to clinical services or deficiencies in safety liable to cause serious injury and/or prosecution”.

272

NHS Digital, ’Estates Return Information Collection (ERIC) 2021/22, Data Definitions’, 13 October 2022, retrieved 16 October 2023, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/estates-returns-information-collection/england-2021-22

Similarly, tight capital budgets have prevented departments from replacing buildings constructed using reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC), some of which are now considered too dangerous to use. For example, in 2020 DfE requested funding to rebuild and refurbish around 200 schools a year but was only granted funding for a quarter of that.

273

Comptroller and Auditor General, Condition of school buildings, Session 2022–23, HC 1516, National Audit

Office, 2023, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/condition-of-school-buildings.pdf

Many public services are using technology that is not fit for purpose. In the criminal courts, a recent survey found less than half of salaried and fee-paid judges said that internet access at court was excellent or good. 274 Courts and Tribunal Judiciary, ’Judicial Attitude Survey 2022’, 4 April 2023, retrieved 16 October 2023, www.judiciary.uk/guidance-and-resources/judicial-attitude-survey-2022 And Institute for Government research published earlier this year heard from interviewees about the impact of “slow-loading computers and creaking internal systems” on NHS performance. 275 Freedman S and Wolf R, The NHS productivity puzzle: Why has hospital activity not increased in line with funding and staffing?, Institute for Government, June 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/nhs-productivity Up to 27 out of 220 trusts rely on paper as they still do not have electronic patient records 276 Carding N and Harding R, ‘Revealed: The 27 trusts still without an electronic patient record’, HSJ, 26 May 2022, retrieved 16 October 2023, www.hsj.co.uk/technology-and-innovation/revealed-the-27-trusts-still-without-an-electronic-patientrecord/7032511.article and efforts to improve IT have been undermined by cuts to capital funding. 277 Carding N, ‘NHS tech funding falls to less than £1bn’, HSJ, 9 February 2023, retrieved 16 October 2023, www.hsj.co.uk/technology-andinnovation/nhs-tech-funding-falls-to-less-than-1bn/7034194.article

The NHS is also short of critical equipment. Among OECD countries, the UK has the fifth lowest number of CT and PET scanners and MRI units per capita. 278 Wickens C, Why do diagnostics matter?, The King’s Fund, October 2022, p. 24, www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-10/Why%20do%20diagnostics%20matter%20online%20version_0.pdf As a result, hospitals are able to conduct fewer diagnostic tests, extending the size of the elective backlog and waiting times for patients.

Taken together, this underinvestment means that public services are getting less out of each member of staff than they would otherwise. This partly explains the ‘productivity puzzle’ seen in the NHS, and particularly hospitals 279 Freedman S and Wolf R, The NHS productivity puzzle: Why has hospital activity not increased in line with funding and staffing?, Institute for Government, June 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/nhs-productivity – that is, why extra cash funding has not helped boost activity as hoped.

The government has recognised the importance of capital investment, with Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor, saying in the autumn statement 2022: “When looking for cuts, capital is sometimes seen as an easy option. But doing so limits not our budgets but our future.” 280 HM Treasury and Hunt J, ’The Autumn Statement 2022 speech’, 17 November 2022, retrieved 16 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-autumn-statement-2022-speech To that end he announced that capital allocation made in 2021 would be protected for the spending review period, and would then be maintained in cash terms for the following three years. This includes funding to expand and improve the prisons, hospitals and schools estates. 281 Department of Health and Social Care Media Centre, ’New Hospital Programme - media fact sheet’, Department of Health and Social Care, 25 May 2023, retrieved 16 October 2023, https://healthmedia.blog.gov.uk/2023/05/25/new-hospital-programme-media-fact-sheet , 282 Institute for Government interview.

Despite higher inflation eroding the value of the 2019 settlement, capital budgets for this spending review period are still set to grow more quickly than during the multi- year spending reviews in the 2010s. However, this is from a relatively low base, and below the growth rates seen in the 2000s.

* General government gross fixed capital formation.

** £10.2bn in hospitals, £10.6bn in school, £1bn in criminal courts, £1.4bn in prisons, £14.0bn across the road network.

High turnover and loss of experienced staff have further hampered services

Workforce turnover can help to improve services by bringing in new staff with different backgrounds and experiences. But the evidence suggests that the high rate of churn in many public services is damaging service productivity and can lead to worse outcomes for services users 286 Fright M, Davies N and Richards G, Retention in public services, Institute for Government, October 2023; www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/staff-retention-public-services – for example, students’ test scores are reduced by higher teacher turnover. 287 Gibbons S, Scrutinio V and Telhaj S, ’Teacher Turnover: Does It Matter for Pupil Achievement?’, ERIC, (no date), retrieved 16 October 2023, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED583870

Leaving rates are high across all public services. In the 12 months to June 2023, one in ten workers left NHS hospital and community care settings (11.2%). Although this is below the highs of 12.5% in the year to summer 2022, during the second year of the pandemic, it is still above 2019 levels. And in children’s social care, 17.1% of the workforce left in the last financial year – a series high – up from 15.1% in 2019/20. It may be that higher leaving rates partly reflect the loss of staff who would have left in 2020/21 but stayed longer due to the pandemic; if so, leaver rates could return to pre- pandemic levels. But for now they remain elevated in many services.

Many of those who have left public services roles had years of experience – and were therefore likely to be among the most effective in their roles.*, 288 Fright M, Davies N and Richards G, Retention in public services, Institute for Government, October 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/staff-retention-public-services For example, half of band 3–5 prison officers in 2022/23 have fewer than five years’ experience, compared to 23% in 2009/10, while the proportion with more than 10 years’ experience fell from 56% to 31% over the same period. And in nursing, the overall number of registered nurses with more than 30 years’ experience has fallen slightly in recent years, whereas the number with fewer than five years’ experience has increased by more than 40%.

There is also greater use of temporary staff in some services. In children’s social care, the number of agency social workers in post increased by 13% over the past year and is now at the highest level on record. 296 Department for Education, ’Children’s social work workforce’, 23 February 2023, retrieved 16 October 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-s-social-work-workforce/2022 The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan stated that spending on agency staff rose 23% between 2018/19 and 2021/22 to reach £2.96bn. It also cites evidence that “use of temporary staffing – particularly agency staff – can have a negative impact on patient and staff experience, and continuity of care”. 297 NHS England, NHS Long Term Workforce Plan, June 2023, p. 30, www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/nhs-long-term-workforce-plan-v1.2.pdf Previous Institute for Government research also heard from interviewees that agency staff in hospitals tend to make ‘less discretionary’ effort (working more hours than one’s contract sets) than those on the payroll, contributing to lower productivity. 298 Freedman S and Wolf R, The NHS productivity puzzle: Why has hospital activity not increased in line with funding and staffing?, Institute for Government, June 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/nhs-productivity

As well as being less effective, agency staff are also more expensive. For example, Freedom of Information releases have suggested that, once agency fees and the like are added, the NHS can be charged up to £2,500 per shift per nurse 299 Triggle N, Hayward C, Rodgers J, ‘Desperate NHS pays up to £2,500 for nursing shifts’, BBC News, 11 November 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-63588959 and £5,200 per shift per doctor 300 Pym H, ‘Hospitals in England pay £5,200 for one agency doctor’s shift’, BBC News, 11 December 2022, www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-63935416 – several times the cost of employing experienced nurses or doctors directly. Similarly, although supply teachers are often paid less per day than equivalently experienced full-time teachers, the cost to schools is normally substantially higher again due to agency mark-ups, compliance costs and other fees. 301 National Education Union, ’Supply teachers: Pay, conditions and working time’, (no date), retrieved 16 October 2023, https://neu.org.uk/advice/supply-teachers-pay-conditions-and-working-time

* In the case of prison and police officers, large numbers of experienced staff left in the early 2010s through voluntary redundancy schemes introduced by the coalition government to cut staff as part of efforts to reduce public spending.

There are lots of contributory factors to high leaver rates

The precise reasons for leaving a job or profession will vary from person to person, but the key factors driving high public service workforce leaver rates are pay, workloads, unsociable hours, changing societal norms and dissipating goodwill. A tight labour market is also making it easier for staff to find work elsewhere.

Many of these are long-running problems. In the 2010s, the government made ‘efficiencies’ by holding down public sector pay. Previous Institute for Government and CIPFA work has estimated that the two-year pay freeze between 2011 and 2013, and a 1% average pay cap from 2013 to 2017, saved the government £10bn–£20bn per year from 2017 onwards. 302 Pope T, Hoddinott S and Fright M, ’Austerity’ in public services: lessons from the 2010s, Institute for Government, 25 October 2022, retrieved 16 October 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/austerity-public-services-lessons-2010s However, as a result the public sector pay differential – the difference between public and private sector pay – fell substantially and, taking account of bonuses, turned negative.

Once employer pension contributions are taken account of, total public sector remuneration was still higher, but in 2021 the gap was the smallest it had been since at least 2005. More recently, public sector wages have been further eroded by high levels of inflation, meaning the gap is likely to have shrunk further.

As a result, pay for critical public service staff such as police officers, teachers and nurses has not kept pace with private sector wage rises, and is also worth less in real terms.* Unsurprisingly, staff are unhappy. For example, the proportion of respondents to an annual Police Federation survey reporting dissatisfaction with basic pay increased from 69% in 2020 to 86% in 2022. 305 Police Federation of England and Wales, Pay and Morale 2022 - Headline Report, (no date), www.polfed.org/media/18245/pay-and-morale-2022_headline-report.pdf And the latest NHS staff survey found only 25.6% of staff were satisfied with pay, 12.3 percentage points lower than in 2019. 306 NHS, NHS Staff Survey 2022: National results briefing, March 2023, www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/static/8c6442c8d92624a830e6656baf633c3f/NHS-Staff-Survey-2022-National-briefing.pdf In addition to its contribution to high leaving rates, pay is also the key driver of strike action (discussed in more detail below), which is also hugely disruptive to public services.

On workloads, while many public service jobs have always been demanding, there is evidence that the pandemic has increased workloads even more, 324 Fright M, Davies N and Richards G, Retention in public services, Institute for Government, October 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/staff-retention-public-services and excessive workloads are cited by many who are considering leaving. For example, “feeling under too much pressure” was the second most common reason given by nurses for thinking about or planning to leave their role. 325 Royal College of Nursing, ’RCN Employment Survey 2021‘, 30 December 2021, retrieved 16 October 2023, www.rcn.org.uk/Professional-Development/publications/employment-survey-2021-uk-pub-010-075 And research by the Department for Education found that workload was given as a reason by almost all teachers considering leaving the state sector in the next 12 months for reasons other than retirement (92%). 326 Adams L, Coburn-Crane S, Sanders-Earley A and others, Working lives of teachers and leaders - wave 1, Department for Education, April 2023, p. 19, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1148571/Working_lives_of_teachers_and_leaders_-_wave_…

Public services can also involve unsociable hours, particularly those such as hospitals and the police, which run 24 hours a day, all year round. These services require staff to work in shift patterns, which likely contributes to many staff reporting low levels of wellbeing. For example, only a little over half of respondents to the NHS Staff Survey said they have balance between home life and work life, 327 NHS, NHS Staff Survey 2022: National results briefing, March 2023, www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/static/8c6442c8d92624a830e6656baf633c3f/NHS-Staff-Survey-2022-National-briefing.pdf and just under half of police officers reported they have poor work–life balance. 328 Police Federation of England and Wales, Pay and Morale 2022 - Headline Report, (no date), www.polfed.org/media/18245/pay-and-morale-2022_headline-report.pdf In comparison, a survey of 2,000 UK employees published in 2022 found that only 31% did not feel that they have a good work–life balance. 329 Cebr, The Future of You, Lenovo, January 2022, p. 17, https://techtoday.lenovo.com/origind8/sites/default/files/2022-03/The%2520Future%2520of%2520You%2520-%2520Whitepaper.pdf

Such working patterns are increasingly unattractive given changing societal norms. Particularly for graduate roles, home and ‘flexi’ working arrangements have also become much more common in other sectors and a failure to keep up with the wider economy has left many public service employers at a comparative disadvantage. 330 Fright M, Davies N and Richards G, Retention in public services, Institute for Government, October 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/staff-retention-public-services This desire for greater flexibility is behind the decision by some nurses and doctors to take up agency or locum roles, rather than direct NHS employment. 331 Institute for Government interview.

These factors, particularly pay and poor working conditions, have contributed to a loss of goodwill among public service workforces, with many giving this as a key reason for quitting. For example, of nurses planning to leave, 70% cited feeling undervalued. 332 Royal College of Nursing, RCN Employment Survey 2021, 30 December 2012, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.rcn.org.uk/Professional-Development/publications/employment-survey-2021-uk-pub-010-075 Similarly, morale (98%) and how the police are treated by the government (96%) were the top two reasons given by police intending to resign. 333 Police Federation of England and Wales, Pay and Morale 2022 - Headline Report, (no date), www.polfed.org/media/18245/pay-and-morale-2022_headline-report.pdf

These issues are particularly problematic given the tightness of the labour market. Across the wider economy, there are more vacancies than job seekers, 334 Institute of Directors, ’More vacancies than unemployed, for the first time ever‘, press release, 11 October 2022, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.iod.com/news/iod-press-release-more-vacancies-than-unemployed-for-the-first-time-ever meaning employers have to do more to retain and recruit staff. We heard in interviews that many public services are struggling with competition from the private sector – and elsewhere in the public sector. Better pay or working conditions in the retail and hospitality sectors has tempted away many working in lower paid public service roles, including care workers and administrators. Public sector employers similarly find it difficult to compete with the private sector wages available to managers, analysts and IT professionals.

Within the public sector itself, worse remuneration packages in adult social care, prisons and community pharmacies have resulted in a net loss of staff to the NHS, police and primary care respectively. Competition also comes from overseas, particularly for doctors and nurses, where the higher pay and standard of living available has seen many move to countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

* This is also true if 2008 is taken as the starting point, though the difference is smaller as public sector wages outperformed those in the private sector between 2008 and 2010.

The government is relying on immigration to fill workforce gaps in some services

There has been a substantial increase in the number of international recruits starting in general practice, hospitals and adult social care – all services that have experienced some form of workforce crisis since the pandemic. Most strikingly, in the 12 months to June 2023, the number of British nurses and health visitors fell by 2,763, while the number from the rest of the world increased by 11,984. 335 NHS Digital, ‘NHS workforce statistics, HCHS staff in NHS Trusts and core orgs June 2023, Turnover tables’, Turnover, age & nationality table, 28 September 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-workforce-statistics/june-2023 And in adult social care, new joiners from overseas over the past year alone account for 3.6% of all filled posts in the sector.

International recruits can improve public services by bringing different ways of working and perspectives, but relying on them to fill workforce gaps comes with risks. First, international staff are generally more expensive to recruit. Research by Nuffield Trust found that it costs £10,000–£12,000 to recruit a single nurse from overseas. However, this does mean that the government avoids the training costs for these staff. This can be much higher; for example, the typical cost of training a nurse domestically is at least £26,000. 336 Palmer B, Leone C and Appleby J, Return on investment overseas: lessons for the NHS, Nuffield Trust, October 2021, p. 8, www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-10/1633336126_recruitment-of-nurses-lessons-briefing-web.pdf

Second, those recruited may not stay in their roles as long. While international nurses from outside the EU are more likely to stay in the NHS as a whole and in the same organisation than those from the UK, those from the EU leave more quickly. 337 Palmer B, Leone C and Appleby J, Return on investment overseas: lessons for the NHS, Nuffield Trust, October 2021, p. 8, www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-10/1633336126_recruitment-of-nurses-lessons-briefing-web.pdf Internationally recruited doctors also stay in the service for less time than their British counterparts. 338 General Medical Council, The state of medical education and practice in the UK: The workforce report 2022, October 2022, p. 58, www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/workforce-report-2022---full-report_pdf-94540077.pdf This leads to greater staff churn and higher recruitment costs per year served.

Third, there is a political risk. International recruitment, particularly of care staff, has been a major contributor to the record levels of net migration over the last year. Given the high public salience of immigration levels, 339 YouGov, ’The most important issues facing the country’, (no date), retrieved 17 October 2023, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/education/trackers/the-most-important-issues-facing-the-country and the Sunak government’s rhetoric around immigration, there is a risk that these recruitment routes are shut down, possibly at short notice, allowing little time for providers to identify new sources of staff. Even if high levels of international recruitment remain possible, public services in this country have no control over the numbers trained abroad, how competitive the global marketplace is, or the occurrence of shocks such as Covid that can disrupt the ability of people to move between countries.

Widespread strikes have had a negative impact on public service performance

Public services are facing the greatest level of disruption from strikes in more than a quarter of a century. From August 2022 to July 2023, more than 2 million working days were lost due to strike action in the public sector. This is the most in a 12-month period since at least 1996, when comparable statistics were first published. 340 Office for National Statistics, ‘Working Days Lost due to strike action in the public sector - monthly (‘000s‘)‘, 12 September 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/timeseries/f8xz/lms

Strikes of this magnitude have a big impact on the performance of public services. Academic research looking at strikes by doctors in 2016 found that the disruption did not have an impact on patient volumes, average mortality or readmission rates for emergency patients. However, there were higher readmission rates for Black patients and reductions in the volume of elective procedures. 342 Stoye G and Warner M, ’The effect of doctors’ strikes on patient outcomes: Evidence from the English NHS’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2023, vol. 212, pp. 689–707, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167268123002184?via%3Dihub While it is still too early to fully assess the impact of NHS strikes over the past 12 months, it does appear that the strikes by junior doctors in April 2023 led to a meaningful fall in the number of elective procedures.

Hospitals completed 1.4 million elective pathways in April 2019, but only 1.2 million in April 2023 – 10.4% less. As a result, the elective backlog increased by 84,166 in that month. And in the following month, when there were no strikes by junior doctors, the number of completed pathways rebounded to 1.5 million.

A similarly clear drop in activity can be seen in schools. According to data published by the Department for Education, as little as 43% of pupils attended school during the eight days of national teacher strikes that took place between February and July 2023. Secondary schools were struck particularly hard, with only around a quarter of pupils going into school on strike days. 362 Department for Education, ‘Pupil attendance in schools: Week 28 2023’, 27 July 2023, accessed 23 October 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/pupil-attendance-in-schools/2023-week-28 The absence of so many pupils for more than a week this academic year will only make it harder for schools to catch up on learning lost during the pandemic.

The industrial action by criminal barristers between April and October also reduced the activity that criminal courts were able to undertake. The number of cases processed in crown courts fell from 25,172 in March 2022 to 20,068 in September 2022, again hurting backlog reduction efforts.

The government’s strikes strategy likely extended the strikes, and so their disruption

The widespread strike action over the past year has deep and broad roots, including the coalition government’s decision to hold down public sector pay from 2011 onwards (Figure 0.7), the more recent spike in inflation, and the impact of the pandemic on services and staff wellbeing. Given the UK’s low economic growth, high levels of debt and inflation, and the need to consider the impact of pay offers to some groups on the demands of others, any government would have found it difficult to resolve these industrial disputes.

However, there were important weaknesses in the Sunak government’s strategy for responding to strikes, which likely extended their duration and thus the level of disruption caused to public services. Most critically, ministers refused to negotiate on pay for months. Strikes by NHS staff, including nurses and paramedics, began in December 2022, teachers from the National Education Union in February 2023, and junior doctors in March. This followed months of campaigning and balloting by the unions involved. But it wasn’t until March that an improved offer was made to NHS staff and teachers (with the schools pay dispute only resolved after a further, improved offer), and junior doctors’ pay was eventually raised unilaterally in July, when the government accepted recommendations made by pay review bodies.

For too long the government unreasonably claimed that higher pay was not possible due to the impact on inflation. However, there is no evidence that improved offers below the consumer price index (CPI) but closer to private sector wages would have any impact on inflation. 363 Whiteley P, ’Does public sector pay drive inflation?’, LSE British Politics and Policy blog, 21 February 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/does-public-sector-pay-drive-inflation Indeed, the government eventually made offers at this level. If it had done so earlier – in autumn 2022, rather than spring 2023 – it may have been able to bring at least some of the disputes to an end with far less disruption. Instead, the government’s combative approach, including the introduction of the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act, probably exacerbated resistance from strikers, making it even harder to reach agreement.

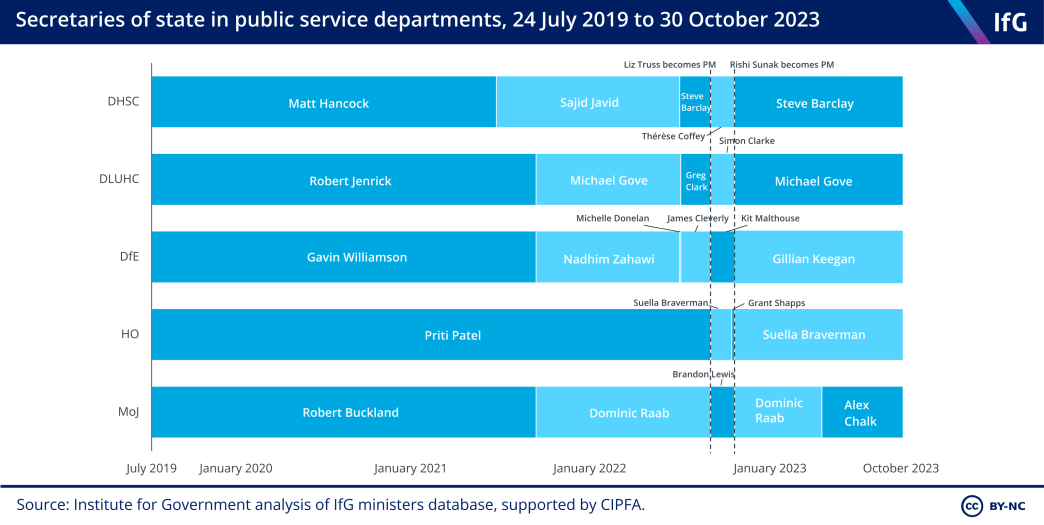

The same is true of the dispute with criminal barristers that was resolved in 2022. Little progress was made by Dominic Raab while he was justice secretary, yet Brandon Lewis, who took a much more conciliatory approach, was able to end the strikes by making an improved pay offer, despite only being in post for six weeks.

Of all the disputes, the one with junior doctors looks most difficult to resolve. The British Medical Association is seeking a 35% pay rise (to bring pay back in line with 2008/09 levels) and there has been little evidence that it is willing to negotiate substantially down from this. Despite the relatively low cost of meeting this demand, 364 Hoddinott S, ’The government needs to rethink its approach to public services strikes’, Institute for Government, 20 April 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/public-services-strikes it would have been difficult for any government to do so given the knock-on impact on the (more modest) pay demands of less well paid NHS staff.

However, even in this case, a different approach by government may have helped. With a more moderate and reasonable public stance, the government could have garnered greater public support, putting pressure on junior doctors to compromise and on consultants* not to join them on the picket line in July. Instead, public support for junior doctors grew from 47% in January to 56% in June. 365 Hall R, ’Majority back NHS strikes despite disruption, polls show’, The Guardian, 2 July 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jul/02/majority-back-nhs-strikes-despite-disruption-polls-show

* Consultants, while still in dispute with the government, have offered not to conduct further strikes if the government will agree to talks facilitated by ACAS, www.bma.org.uk/bma-media-centre/bma-offers- government-route-to-resolve-consultants-dispute-via-acas

Workforce problems will prevent some services returning to pre-pandemic performance levels by the end of the current spending review period in April 2025

Staffing is the single biggest expenditure for public services, accounting for more than half of spending for most of the services covered in this report. While there are a variety of ways that government could improve the performance of services, absent major productivity improvements, the size and composition of workforces will be a key factor.

Policing is the only service covered in this report for which the workforce should enable a return to pre-pandemic performance levels by April 2025. Though there remain shortages in key positions, such as investigators, and the number of PCSOs has fallen, the number of police officers has increased by more than 20,000 and by April 2025 many of these recruits should be more effective and be contributing to better police performance, particularly in terms of the number of charges. Indeed, the recent reversal in the long-term trend of falling charges may be early evidence of this.

At the other end of the spectrum, prisons, criminal courts and children’s social care do not have plans in place that will lead to sufficient recruitment or retention of staff. The problem is most severe in prisons. Most critically, there is no credible plan in place to recruit the number of officers needed to safely staff the huge expected increase in prisoners over the next few years due to the greater police numbers cited above; this will also affect courts, in which the current workforce of judges and barristers is likely to be insufficient to process a substantially higher volume of cases in the crown court.

Demands on children’s social care services are rising but the number of children’s social workers fell over the past year. With evidence that caseloads are becoming more complex, workloads already becoming unmanageable for many – and in the absence of a workforce strategy to ease pressure on staff – it appears highly unlikely that this workforce will be sufficient to meet demand.

The workforce situation in the other services is less clear. However, although strike action is only ongoing in hospitals, the ability of the government to agree future pay deals will have a big impact on recruitment and retention across all the services covered in this report. The ease of doing that will depend on inflation and the health of the wider economy.

Funding

Funding settlements are now worth less due to higher pay awards and inflation

Budgets for the 2022/23–2024/25 period were originally set at the 2021 spending review. Additional funding for the NHS, schools and adult social care was then announced at the 2022 autumn statement. However, the value of these cash settlements has been eroded over time, due to higher than anticipated pay awards and inflation.

The 2021 spending review anticipated that public sector wages would increase by 2–3% annually across the spending review period. However, the government has been forced to make substantially higher pay awards as a result of inflation and industrial action, as covered above. For example, the cost of the improved offer to nurses, ambulance staff and other NHS workers (those on the Agenda for Change pay scale) 366 NHS, ’Agenda for change – pay rates’, April 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/working-health/working-nhs/nhs-pay-and-benefits/agenda-change-pay-rates was an additional £2.7bn in 2022/23 and an approximate ongoing cost of £1.3bn per year from 2023/24 onwards. 367 Brown F, ’NHS pay rises will cost £4bn and will be funded from ’areas of underspending’, govt says’, Sky News, 17 March 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, https://news.sky.com/story/nhs-pay-rises-will-cost-4bn-and-will- be-funded-from-areas-of-underspending-govt-says-12836167 In March, when this deal was agreed, the government did not state how it would be funded.

In July, when the government accepted the recommendations of pay review bodies (PRBs) for other public service workforces, it said it would not borrow to fund these. This means that these will have to be paid for either through increased revenue, or by cutting spending. The government has stated that some of the funding will come from increases to visa fees and the immigration health surcharge. 368 Hassan B N, ’Why are UK visa application fees rising? Rishi Sunak announces change‘, Evening Standard, 14 July 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/why-uk-visa-fees-cost-rising-b1094477.html However, most will come from reallocating existing spending, either from within departmental budgets or elsewhere across government.

The increase in teachers’ pay will also be funded from the existing DfE budget for 2023/24 and 2024/25, with the government stating that this is to come from reprioritisation of underspends 369 The Education Hub, ’Teacher strikes: Everything you need to know about the 2023/24 teacher paya ward’, Department for Education, 13 July 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2023/07/13/teacher-strikes-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-2023-24-teacher-pay-award – expected to be partly from the National Tutoring Programme – rather than cuts to school budgets. This use of a one-off allocation to fund an ongoing liability will store up problems for the next spending review.

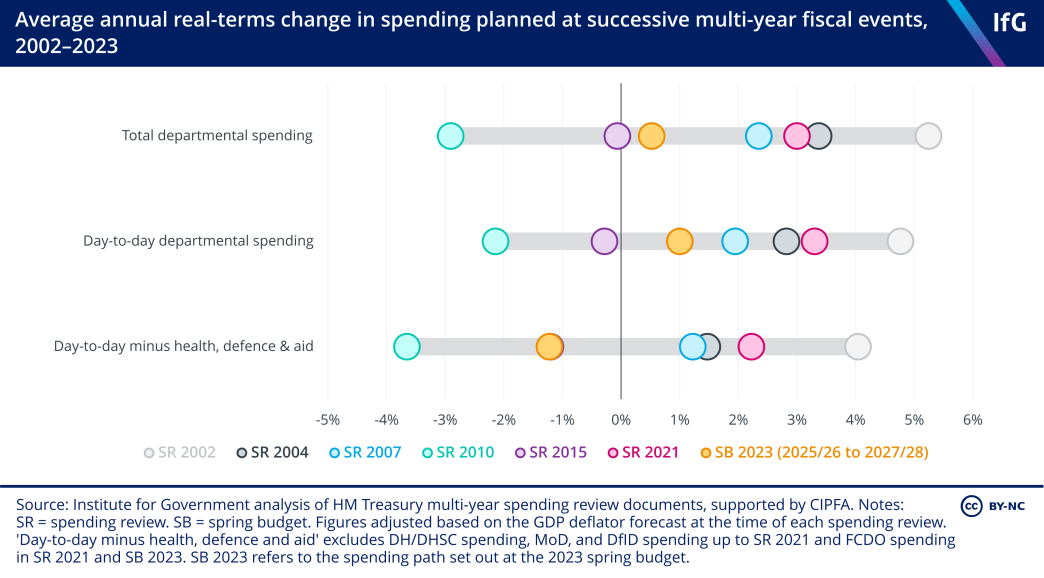

At the time of the 2021 spending review, the OBR projected that the GDP deflator (the measure of inflation used by the government to assess real-terms increases in departmental spending) would be 2.2% in 2023/24. By the 2022 autumn statement this had risen to 3.2% and the latest forecast from the OBR is that it will be 2.5% – though this is likely to prove too low as inflation has recently proved more persistent than expected in March 2023. As a result, spending allocations are now less generous than they were (see Figure 0.10).

Some services are facing even higher sector-specific inflation than this. Interviewees told us that the unit costs of adult social care packages are now much higher than they were a year ago. According to a survey of directors of adult social services, this has been driven by increasing complexity of care needs, staffing costs and wider inflationary pressures. 370 Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, Spring Survey 2023, 2023, p. 17, www.adass.org.uk/media/9751/adass-spring-survey-2023-final-web-version.pdf Similarly, we heard that the unit cost of residential children’s social care placements has also risen substantially, with increased demand and limited capacity putting local authorities in a weak bargaining position with private providers.

The inflation-driven rise in interest rates could also reduce spending on local authority-provided public services. In recent years, some local authorities took out loans to finance commercial investments, hoping that those would then generate a future stream of income. 371 Gilmore A, ’Debt refinancing a major concern for Croydon Council as interest rates rise’, Room151, 27 June 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.room151.co.uk/151-news/debt-refinancing-a-major-concern-for-croydon-council-as-interest-rates-rise Those with variable-rate or short-term loans that need to be refinanced will face higher interest rates, increasing annual repayments, and reducing the funding available to front-line services. Some private sector providers will also be affected. The Competition and Markets Authority has identified that some of the largest providers of residential care services for children are owned by private equity firms and carry high levels of debt. This risks a “disorderly failure of highly leveraged firms” that could affect the placements of children in care. 372 Competition and Markets Authority, Children’s social care market study final report, 22 March 2022, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-social-care-market-study-final-report/final-report The loss of these providers could push up prices even further.

Parts of local government and the NHS are already running deficits

According to government figures, local authority usable reserves in England increased from 45% of service expenditure in 2019/20 to 63% in 2021/22. However, data issues mean that some councils’ reserves are likely overstated 373 Institute for Government interview. and the precise figures depend on how the distribution of emergency business rates relief at the beginning of the pandemic is accounted for.

Comprehensive data on reserves in 2022/23 will not be published until the end of this year. However, there is extensive evidence that many local authorities have run large deficits in recent years. For example, Kent County Council overspent its 2022/23 budget by £44.4m, with the additional money coming from reserves. 374 Gilmore A, ’Kent County Council reports nearly 45m budget gap’, Room151, 3 July 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.room151.co.uk/treasury/kent-county-council-reports-nearly-45m-budget-gap Bradford Metropolitan District Council overspent by £32m in 2022/23, largely due to higher- than-expected children’s social care costs. The council’s director of finance noted that remaining reserves would likely only be sufficient to cover 2023/24 and that “reserves are reducing at an unsustainable rate.” 375 Gilmore A, ‘Down £100m in one year: Bradford’s reserves drop at ‘an unsustainable rate’, Room151, 4 April 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.room151.co.uk/treasury/down-100m-in-one-year-bradfords-reserves- drop-at-an-unsustainable-rate In this financial year, Kirklees Council has agreed to draw down £25m from reserves to partially fill a £43m budget deficit, 376 Marlow A, ‘Kirklees Council has ‘no option’ but to save £19m to address its £43m budget shortfall’ https://www.dewsburyreporter.co.uk/news/people/kirklees-council-has-no-option-but-to-save-ps19m-to-address-its-ps43m-budget-shortfall-4038447 and East Sussex County Council is spending £5.6m from reserves on road repairs. 377 BBC News, ‘Council to dip into reserves for road repairs’, 30 June 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c0wvkd0lx31o Reserves can only be used once and are not a long-term solution to persistent deficits.

Three quarters of local authorities also had cumulative deficits on the part of local authorities’ education budgets reserved for schools spending in 2021/22, largely as a result of their spending on statutory special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) support, with the combined deficit totalling £1.4bn.* Local authorities with large deficits can access funding from central government through ‘safety valve’ deals. In exchange for additional funding, local authorities are required to eliminate their in- year deficits by taking action to reform their SEND provision – which in some cases can include moving learners from the independent special school sector, where the cost is higher, to state provision. Since 2020/21, some 34 local authorities have entered into such agreements, with the DfE committing nearly £1bn in return. 378 Booth S, ‘Council SEND deficit bailouts hit £1bn as 20 more issued ‘, https://schoolsweek.co.uk/council-send-deficit-bailouts-hit-1bn-as-20-more-issued

In the NHS, at least 14 integrated care systems (ICSs), out of a total of 42, ended 2022/23 with a budget deficit. 379 Anderson H, ‘Revealed: the 14 ICSs admitting they will end the year in deficit‘, HSJ, 27 February 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.hsj.co.uk/finance-and-efficiency/revealed-the-14-icss-admitting-they-will-end-the- year-in-deficit/7034308.article Many will run a deficit in 2023/24 as well. At the July meeting of the NHS England board, the chief financial officer reported that 15 had submitted a deficit plan for 2023/24, with a total forecast overspend of £720m. 380 Kelly J, ‘Financial performance update’, NHS England, 27 July 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/financial-performance-update

* In December 2022 the government announced that local authorities could keep these deficits off their balance sheets until 2025/26, www.lgcplus.com/services/children/send-deficits-kept-off-budgets-for-another-three-years-12-12-2022

Most services have not had adequate funding to return to pre-pandemic performance levels by April 2025

Funding for general practice is insufficient to return the service to pre-pandemic performance levels. The current five-year GP contract started in 2019/2020 and runs until 2023/24, but higher than anticipated inflation means that real-terms core funding for GPs will be 3.1% lower in 2023/24 than in 2019/20, despite patient numbers registered with general practice increasing by 5.7% over the same period. There has also been underinvestment in general practice capital, which is a major impediment to expanding access to the service and also means that the successfully expanded direct patient care workforce is not being used effectively.

In contrast to general practice, spending on hospitals has increased substantially since 2019/20, with a further £3.3bn for each of 2023/24 and 2024/25 announced at the 2022 autumn statement. As shown in Figure 0.10, spending has outpaced demand and should, in theory, be sufficient to enable hospitals to return to pre-pandemic performance levels. However, the shock of the pandemic, combined with pre-existing problems such as underinvestment in capital and loss of experienced staff, has reduced hospital productivity. 385 Freedman S and Wolf R, The NHS productivity puzzle: Why has hospital activity not increased in line with funding and staffing?, Institute for Government, 13 June 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/nhs-productivity The government does not have credible plans in place to improve hospital productivity, so planned spending will not be enough.

We assess the financial sustainability of adult social care, children’s social care and neighbourhood services together, as all are delivered by local government. Like the NHS, local authorities received a funding boost at the 2022 autumn statement in the form of increased funding for adult social care. As a result, local authority spending power is now projected to rise by 4.7% in real terms per year on average in 2023/24 and 2024/25. In addition to outpacing inflation, the funding increase should be enough to meet ongoing demographic demand and maintain performance at current levels. In children’s social care, that will mean performance in April 2025 will be broadly similar to that seen before the pandemic. However, in both adult social care and neighbourhood services, where performance has declined over the past three years, the funding is unlikely to be enough to see a sufficient improvement. These judgments are in aggregate and the situation will vary widely across the country due to differing demands, local priorities and effectiveness, and the ability of local authorities to raise council tax in line with central government expectations.

Schools also did well out of the 2022 autumn statement, receiving an additional £2bn in both 2023/24 and 2024/25. The typical school is in a relatively stable financial position, at least compared to most of the services covered in this report, and schools will be able to draw on extra DfE funding to cover the cost of the higher teacher pay offer in this spending review period. While there is limited evidence on the impact of the pandemic on attainment at key stage 4, the drop in pupil attainment at key stage 2 has been sizeable. Inadequacies in the design and funding of the government’s catch- up programmes mean it is unlikely that this drop in performance will be reversed before April 2025.

Police forces were provided no additional funding in the autumn statement 2022, and across the three-year spending review period we calculate that demand will rise by 1.7% for police services, while spending (following the newly agreed pay deal and the government’s additional funding to pay for the deal) will fall by 2%. However, the police received a substantial boost to funding in the three years before this. As a result, overall spending is expected to rise on average by 0.7% per year in real terms between 2019/20 and 2024/25, which should be enough to allow the police to return to pre-pandemic performance.

The situation in criminal courts and prisons is much harder. Like the police, they were not provided additional funding in the autumn statement 2022. However, their settlements in earlier years were also less generous. Demand for these services is also likely to rise more quickly due to the increased number of charges that 20,000 additional police officers have started – and will likely continue – to generate. Over the spending review period, we calculate that the growth in demand for criminal courts and prisons will outstrip the growth in funding by 5.0 and 4.1 percentage points per year respectively.

Funding in the next spending review period is even tighter and would see almost all services performing worse in 2027/28 than on the eve of the pandemic

The funding situation for public services will be difficult for the rest of this spending review period, but the situation from April 2025 onwards will be even harder.

The plans set out in the 2022 autumn statement and the 2023 budget show that total departmental spending is due to grow by 1% per year in real terms between 2025/26 and 2027/28. However, assuming that NHS spending grows at 3.6% per year in real terms over this period – an amount the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates would be required to meet the commitments laid out in the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan 386 Warner M and Zaranko B, Implications of the NHS workforce plan, Institute for Fiscal Studies, August 2023, p. 2, https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-08/R272-Implications-of-the-workforce-plan-IFS%20%282%29.pdf – that aid spending and defence spending grow in line with GDP, and that the government will continue to allow local authorities to raise revenue through council tax increases, the settlements for unprotected areas of public spending will be much less, averaging -1.2% per year in real terms.

This would make it the tightest spending review since 2015. Notably, the Cameron and May governments found it impossible to stick to those 2015 plans. 387 Atkins G and Lanskey L, The OBR’s forecast performance, Office for Budget Responsibility, Working Paper no.19, August 2023, p. 12, https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/WP19_The_OBRs_forecast_performance_Aug23.pdf Instead, they felt it necessary to provide additional funding to the NHS, adult social care and the criminal justice system due to poor performance. In 2025, the performance of most of the services covered in this report will be much worse than it was a decade earlier. The next government is therefore likely to face huge public and political pressure to provide public services with more generous funding settlements. Indeed, speaking at an Institute for Government event, Lord Gus O’Donnell, the former cabinet secretary, said that the spending plans were “totally unsustainable”. 388 Institute for Government, ‘Why does the UK underinvest in public service infrastructure – and how can the problem be fixed?’, Institute for Government, 25 September 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/event/uk-underinvest-public-service-infrastructure

Some services will fare better than others under current spending plans. GPs and hospitals will see a meaningful improvement in spending, largely because the government will need to raise spending on the NHS to meet the commitments laid out in the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan. 390 NHS England, NHS Long Term Workforce Plan, June 2023, www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-workforce-plan Those increases – if the government sticks to them – are likely to outstrip inflation and the increase in demand for those services.

In local government and schools the situation is less certain. Funding is around what might be needed to meet inflation and demand pressures, though for different reasons. Local authorities will continue to benefit from central government’s policy of allowing them to raise council tax, while demand for school places is expected to decline as the number of children falls in coming years, as the end in 2013 of a baby boom is felt across the education system.

Under current plans, the criminal justice system looks to have the lowest levels of funding compared to its needs. Expected demand for police, prisons and criminal court services far outstrips the funding currently implied by the government’s plans.

Given the current performance of services, the expected trajectory over the rest of the current spending review period and the spending plans discussed above, children’s social care is the only service we analyse that is likely to have sufficient funding to exceed pre-pandemic performance in 2027/28. Unlike children’s social care, the other local government services – adult social care and neighbourhood services – are performing worse than on the eve of the pandemic and the tightness of implied local government funding is unlikely to be enough for that position to be reversed. The same is true of schools, where funding is probably insufficient to make up for lost learning due to Covid.

In hospitals and general practice, increased funding in the next spending review is unlikely to reverse many of the trends – underinvestment in capital, staff retention problems, and system co-ordination issues, among others – all of which have been exacerbated since the start of the pandemic.

But the situation looks most stark for the criminal justice system, where anticipated progress on police performance would be reversed and dire performance in criminal courts and prisons would only worsen if the next government sticks to these spending plans.

The next government will face very difficult spending decisions – whoever is in office

A general election must happen by the end of January 2025 at the latest, with most expecting a spring or autumn 2024 vote. But whoever wins that election will inherit a delicate funding situation. If, as expected, that government does find it impossible to stick to current spending plans from 2025/26 onwards, then it will face difficult choices about how to raise the money.

The sums involved will be large. For example, if the government wished to increase total* or day-to-day departmental spending by as much as the 2007 spending review, this would cost an additional £34bn or £14.7bn respectively in 2027/28. This amounts to 1.4% of GDP for total spending, and 0.6% of GDP for day-to-day spending. Even a 1% real-terms annual day-to-day spending increase for non-health and aid services would cost £12.7bn. A £34bn increase in total departmental spending in 2027/28 is the equivalent of raising the basic rate of income tax by 5p, all rates of income tax by around 4p or VAT by around 4p. 401 HM Revenue and Customs, ‘Direct effects of illustrative tax changes’, 30 June 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/direct-effects-of-illustrative-tax-changes

In short, something would have to give: sustained higher spending on public services cannot be funded by short-term and relatively small measures such as utilising one- off underspending and increasing visa fees. If the next government wishes to raise such additional revenue then, without a major boost to economic growth, it will need to do so via key taxes.

Alternatively the government could seek to cut spending elsewhere or borrow more. However, it is hard to see where savings of this scale could be made and the next government may be reluctant to undertake additional borrowing to fund public service spending as there is currently little room relative to the fiscal rule to have debt falling as a share of GDP (which Labour has also committed to).

* Total is the sum of resource (day-to-day) spending and capital spending.

Looking ahead

Performance improvement is possible but requires a big change in government’s approach

Whoever forms the next government will face a daunting task just to return services to pre-pandemic levels of performance, never mind those seen in 2010. The problems described above are deeply entrenched and in some cases the result of decades of decisions. The next government should not expect to fix them over a single parliament. But the public should expect them to start the process. The longer that government takes to chart a better course, the harder it will be.

There is no meaningful fat to trim in public services – budgets have been under sustained pressure for more than a decade and there are no more easy cuts that can be made without damaging performance further. But services can run more efficiently, with higher activity and standards delivered on existing staffing and funding levels. Yet unlocking these productivity improvements will require a change in approach and, in some cases, upfront investment. That will not be simple, but the potential benefits are huge. For example, between 1997 and 2009, UK public sector quality adjusted productivity increased by just over 5%. 402 Office for National Statistics, ‘Public service productivity estimates: total public service, 2020, Worksheet 3: Quality Adjusted Productivity Indices by Service Area, 1997 to 2020, UK.’, 28 April 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/economy/economicoutputandproductivity/publicservicesproductivity/datasets/publicserviceproductivityestimatestotalpublicservice Delivering a productivity increase of 5% across the services covered in this report now would be the equivalent of £11.8bn extra in funding.

The purpose of this report is not to set out an exhaustive range of solutions but to identify the key questions that any government serious about public service performance should be asking.

1. How can workforce disputes be avoided and experienced staff retained?

As discussed in detail above, the government’s strikes strategy has likely extended the duration of pay disputes, and thus exacerbated the disruption caused to public services. And at least some industrial action is likely to continue. At the time of writing, junior doctors have committed to continued striking and consultants have said that they will undertake further industrial action if an improved offer is not made by early November. 403 Sharma V, Open letter to Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, BMA, 2 October 2023, retrieved 17 October 2023, www.bma.org.uk/media/7651/letter-to-prime-minister-from-bma-consultants-cttee-021023.pdf

Disagreements between government, unions and workforces over pay are inevitable, but it is in the interests of everyone that they are settled amicably. Pay review bodies (PRBs) are a helpful mechanism for doing so but this depends on all participants having confidence in the process. Unfortunately, government actions over the past year have politicised PRBs. Specifically, Rishi Sunak and his ministers have repeatedly emphasised the bodies’ ‘independence’, using this to justify its refusal to reopen pay negotiations. However, PRBs are not truly independent: their remits are set by government; their recommendations can be rejected or partially rejected; and their recommendations are anchored by the government’s evidence on affordability. While the government generally does accept the PRB recommendations and has done in recent years, including when the PRBs have recommended well above the affordability figure, the government’s approach has led to a loss of confidence from unions in the PRB process.