Personal data and coronavirus

How the UK government is planning to use our data to tackle the coronavirus

Will the government’s test and trace service involve the use of an app?

From 24 September, yes. The government announced on 11 September that, following trials in the Isle of Wight and the London Borough of Newham, it would launch a new app in England and Wales. The app will involve contact tracing but also allows users to check alert levels in their area, check into pubs and restaurants, track their symptoms, book a test and keep track of their self-isolation.

On 27 May, the UK government had announced it would start rolling out the NHS Test and Trace service in England the following day, without the use of an app.

How is government planning to use our data to tackle coronavirus?

Contact tracing is only one of the initiatives where government is planning to use personal data – defined by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018 as any information that directly identifies or could be used to identify a living person, or information that could be combined with other information to indirectly identify someone – to counter coronavirus.

NHS England, NHS Improvement and NHSX (the NHS’s digital innovation unit) are building a data platform or data store. This is designed to bring together existing data that is held across the health system, but not linked together, and should give decision-makers at all levels of the NHS key information on everything from bed occupancy to how long Covid-19 patients stay in hospital, helping them to understand how the virus spreads and how to mitigate it.

Microsoft, Palantir, Faculty, Amazon Web Services and Google are among the private companies involved, although the NHS says that all data will remain under its control, and be destroyed or returned in line with the law and contractual agreements once the crisis is over. A group of civil society organisations, privacy advocates and researchers has written to the NHS asking it to provide more information and reduce data sharing risks.

The OASIS project, which is led by NHSX and supported by jHub (the Ministry of Defence’s strategic command innovation hub), is also collecting data from symptom tracking apps built by academics and commercial providers, in order to help the NHS understand the spread of the virus. NHSX says that OASIS will not be looking at the medical needs of individual citizens and ‘will not be receiving, or requesting, data that can identify individuals’.

Individual public services that have been built during the coronavirus crisis will also be using personal data. For example, the Cabinet Office service, ‘Get coronavirus support as a clinically extremely vulnerable person’, requires people to enter their NHS number and is likely to involve the sharing of their data between different parts of government and with supermarkets, which will be governed by data sharing agreements between those organisations.

Some countries have started to investigate immunity certification that could give greater freedom to those who had recovered from the disease, even though much remains unknown about immunity from coronavirus. The government said at its press conference on 21 May that it was looking at ‘systems of certification to ensure people who have positive antibodies can be given assurances of what they can safely do’. Any such schemes would inevitably involve personal data.

What is contact tracing?

Contact tracing involves identifying people who may have been in contact with an infected individual and so may themselves be infected. These people can then be given instructions to help stop the disease spreading further, such as testing or treating them or ordering them to self-isolate or quarantine. This is done routinely for sexually-transmitted diseases without the use of technology, through interviews or individuals giving names and contact details to the authorities, but has never been done on this scale before.

Those infected with a highly-transmissible airborne disease like coronavirus won’t be able to name everyone they came into contact with. Many countries are developing contact tracing apps, designed to tell users if they have come into contact with someone who is ill. This has never really been done before – the technology is untested and unproven, meaning different countries have taken different approaches (outlined below).

Some countries are using technology in other ways to assist contact tracing – particularly those in eastern Asia that have previously faced outbreaks of other coronaviruses like SARS and MERS. In South Korea, for example, the app is voluntary but authorities are supplementing interviews by also using smartphone location data, telecoms data, CCTV and bank records.

Most experts believe that apps, at best, can only ever be part of an effective contact tracing strategy – as countries including the UK (‘a contact tracing app by itself isn’t useful. It has to be part of a wider public health response strategy’), France (‘only one brick’ of a more comprehensive strategy), and Singapore (‘automated contact tracing is not a coronavirus panacea’) have made clear.

How do contact tracing apps work?

The user downloads the app to their phone. Most of the apps being developed use Bluetooth – a wireless technology which allows your phone to exchange information with other devices (such as other phones, smartwatches, or wireless headphones) – to record which other phones (and therefore users) you will have come into contact with, and how close you may have been. The app does this through generating random ID numbers, and collecting the random ID numbers of the app installed on other phones nearby.

It’s when someone becomes ill that the apps being developed take different approaches.

In a decentralized model, the app is designed so everything happens on individuals’ phones and no central server (belonging to, say, a health service or government department) is involved. Every so often, the app is sent a list of the random ID numbers of people who have reported that they may be ill, and checks that list against the ID numbers an individual may have come into contact with. The approaches being developed by Google and Apple (‘Gapple’) and the DP3-T (Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing) protocol developed by a consortium of academics from across Europe are decentralized.

In a centralized model, the app is designed so some central server, belonging to a health service or other organisation, is involved. When a user tells their app that they may be ill, this is reported to the central server that then alerts other phones that may have encountered the infected person. It also means the central authority, such as a health service, is able to use this data to track the spread of the infection. The app developed initially by NHSX, the French government’s StopCovid app, and the PEPP-PT (Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing) protocol are centralized.

In Europe, the UK and France were outliers in developing centralized apps. The UK is now working on a solution that brings together both its initial work and the Google/Apple approach. Germany’s decision to move from a centralized to decentralized approach prompted Ireland and Italy to follow suit. The Norwegian government had taken a centralised approach, but suspended its app after its data protection authority ruled against its use of location data.

There are other variations between different apps globally – some use GPS location data (for example, India), allow users to input other data (something that has apparently been discussed in the UK), or allow medical experts to input data – and there are countries (including China and India) where apps are mandatory, not voluntary.

Are centralized or decentralized apps better?

There are some broad issues common to both types of app, in terms of ethics (mainly privacy), equity and effectiveness. Both approaches involve some risk to personal data; both require relatively new smartphones, not available to the whole population, which risks a digital divide; and contact tracing apps of any kind are untested and unproven and will require a broader programme of testing and contact tracing to work. Apps require large numbers of the population to sign up; using the strength of Bluetooth signals to detect proximity has never been done on this scale before; detection through walls could lead to ‘false positives’; and malicious actors could spread false information or target particular users.

Advocates of the decentralized approach argue that their apps better protect privacy, since data is held on individuals’ phones and not by some central authority that would act as a ‘honeypot’ to attackers. Using Google and Apple software also guarantees technical support from those companies and their platforms – other apps (such as the NHSX one) are having to develop workarounds so they can run properly on Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android operating systems. For example, Apple’s privacy demands of Bluetooth meant Singapore’s TraceTogether app could only run on iPhones that were unlocked all the time, draining the battery.

Advocates of the centralized approach argue that they are designed to give health authorities access to data to better understand and halt the spread of a virus, which is simply not possible in a decentralized system. This central approach also allows an authority to ‘unwind’ false positives (if someone reports they’re ill, forcing those they encountered into self-isolation, but later tests negative) and perhaps understand and guard against ‘griefing’ (deliberate attempts to cry wolf). Some also argue that this approach means sovereign states are making their own decisions, rather than following standards developed by technology companies.

What exactly is the UK approach?

The NHSX started by developing a centralized app. The app would record the first half of a user’s postcode (e.g. SW1Y) and the model of the user’s phone. The random ID number allocated to the phone would be known only to the phone and the NHS server. Where the user did not fall ill, records of other phones encountered would be deleted after 28 days. If a user reported they were ill to the central NHS server, the central server would work out who had been close by and whether to alert them, using Bluetooth signal strength as a proxy for proximity and a risk-scoring algorithm – an example of automated decision-making. If the user subsequently tested negative for the virus, everyone else would be told about the false notification. The National Cyber Security Centre has been working with NHSX to ensure the data is secure.

The government started piloting the app, alongside Public Health England tracing and swab testing, as part of a ‘test, track and trace’ plan on the Isle of Wight in early May 2020. The Isle of Wight was chosen because it is ‘a geographically defined area’ with a sufficient size of population and a single NHS trust covering the whole island. Although the government has published lots of details behind the app (including the source code) and some about the trial (including its data protection impact assessment), it’s not clear exactly when the trial is due to end or what ‘success’, leading to a national rollout, would look like.

On 19 May 2020, junior health minister Lord Bethell told the House of Lords that the trial had shown that ‘people wanted to engage with human contact tracing first’, and the government had therefore ‘changed the emphasis’ of their communications and planning, now ‘regard[ing] the app as something that will come later in support’. On 27 May, the government announced that the NHS Track and Trace service would launch the following day, without the app. In evidence to the health and social care select committee on 3 June, Baroness Harding, the government’s test and trace ‘tsar’, described the app ‘more as the cherry on the cake’ and an end-to-end test and trace service as the ‘bedrock’.

There had been reports that the UK government was developing a second app in parallel, using decentralized Google/Apple technology, and that pressure was growing from Downing Street to change tack. On 18 June, the Department of Health and Social Care announced that it was bringing its work on a centralised app together with the Google/Apple solution – its trials on the Isle of Wight had shown the limitations of the NHSX app, including it not working properly on some operating systems (the software apparently failing to detect nearby Apple phones). However, it also said the Google/Apple protocols '[did] not yet present a viable solution’, particularly when it came to using Bluetooth to estimate distance between phones.

The UK government has announced an app will launch in England and Wales on 24 September, following trials on the Isle of Wight and in the London borough of Newham. This is based on the decentralised Google/Apple protocols. Contact tracing is part of the app, with users who test positive for coronavirus able to share their result anonymously. An algorithm will then be used to determine who has been in ‘close contact’ with the infected person (generally meaning whether you’ve been within two metres of someone for 15 minutes or more).

The app has other functions. It will allow users to:

- check the risk level for their postcode (for example, whether a local lockdown is in place)

- check in to venues like pubs and restaurants by scanning a QR code upon entry, allowing human contact tracers to get in touch if someone with coronavirus was at the venue at the time

- enter symptoms to see whether they might need a coronavirus test

- book a coronavirus test and receive the results

- start a countdown to tell the user when their period of self-isolation has come to an end.

How many people will have to download the app for it to work?

A report by the Oxford Big Data Institute estimated that 56% of the UK population would need to sign up (this is 80% of all smartphone users) to stop the epidemic, but the app could still be useful with lower numbers of users. Some countries have higher estimates of how many people would need to use their app (e.g. Singapore, 75%), while Iceland is believed to have the highest voluntary use of an app (nearly 40%).

More than half of the population of the Isle of Wight had downloaded the app around a week into the trial. A poll for The Observer suggested just over half the UK population would be willing to download the app. Matthew Gould, chief executive of NHSX, told a select committee it would be ‘tough’ to reach the ‘optimal’ levels of download and would ‘require us to earn and keep people’s trust that we are doing it in the right way’.

Some countries – such as China and India – have made the use of their apps mandatory.

Does this all apply to the whole of the UK, or just England?

Health is devolved to the administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Scottish government said it had wanted greater involvement in the development of the initial, centralised NHSX app, but needed to understand how data from that app could work with its plans: such an app might be an ‘enhancement’ but not a ‘substitute’ for the wider approach outlined by the Scottish government in early May. The Scottish government started trialing its own software on 18 May. On 10 September, the Scottish government launched a decentralised app, ProtectScotland, though it says that ‘the app is an extra tool complementing existing person-to-person contact tracing which remains the main component’ of the Scottish system. The app does not have the extra functionality of the one in use in England and Wales.

The Welsh government has long said it was working with the UK government. On 1 June, the Welsh government announced it would roll out contact tracing, with ‘a new online system’ following on 8 June. On 11 September, the UK government announced that Wales, like England, would roll out use of the NHS Covid-19 app.

The Northern Ireland executive originally said it would not encourage residents to download the centralised NHS app that was being developed and that it was working on its own app which could work with the decentralised app being developed in the Republic of Ireland. The deputy first minister expressed personal concerns with the UK’s centralized approach from a ‘human rights point of view’. On 30 July, Northern Ireland became the first part of the UK to launch a contact tracing app – a decentralised one in tandem with Ireland.

Will the government have to pass any new laws?

NHSX told the Science and Technology Committee in late April 2020 that no specific legislation was being considered, arguing there was ‘sufficient legislation and there are sufficient safeguards in place’ for what they wanted to do. The most relevant legislation is the General Data Protection Regulation, incorporated into UK law through the Data Protection Act 2018. The health secretary has also written to health-related bodies requiring them to share and process confidential health information under the Health Services (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002, and issued a direction allowing the security services to access information related to securing NHS and public health networks and systems. NHSX has set up an ethics advisory board for the app. Public Health England is also making use of the National Health Service Act 2006 to share data.

The Ada Lovelace Institute [1] and parliament’s joint committee on human rights have separately called for legislation that should limit how contact tracing apps can use personal data.

What happens next?

The NHS has said that future releases of the now-mothballed centralised app may allow users to provide further information about themselves to help the NHS ‘identify hotspots and trends’. According to a leak reported by Wired, this could also include a coronavirus ‘status’ – a similar system in China has been used to allow people different levels of freedom. The Ada Lovelace Institute has warned of ‘problematic expansion of scope’ from contact tracing or symptom tracking apps to immunity certification.

There had been some controversy about whether data will be deleted when it is no longer required. With contact tracing apps, any data on the user’s device can be deleted, but this is not the case once it is submitted to the central server – i.e. when somebody reports that they are ill. NHSX told the joint committee on human rights that, at the end of the crisis, data would either be deleted or ‘fully anonymised in line with the law, so that it can be used for research purposes’. This is not a concern with decentralised apps.

The government’s coronavirus recovery plan notes that the government has a ‘responsibility to build the public health and governmental infrastructure… that will protect the country for decades to come’. As we have previously suggested, this could involve changes in the way government uses citizens’ data. The recovery plan also refers to ‘an unprecedented degree of data-collection, as many Asian countries implemented after the SARS and MERS outbreaks’, even though the UK has not gone as far as these countries in using location, CCTV or financial data.

What are the implications for personal data from contact tracing not involving an app?

Public Health England has published a privacy notice outlining the data it is planning to collect on people with coronavirus (kept for 20 years) and their contacts (kept for five years, the data being kept for so long to ‘help control the spread of coronavirus, both currently and possibly in the future’). PHE says the data will be kept secure in its ‘secure cloud environment’ and only seen by those with a ‘specific and legitimate role’ in the response and working on NHS Test and Trace, and it may be shared with NHS doctors and nurses working alongside PHE. Action by the Open Rights Group means data will now be kept for eight, rather than 20 years.

PHE is allowed to use this data in the public interest, particularly in the area of public health, under GDPR, and share it under section 251 of the National Health Service Act 2006, which temporarily lifts the duty of confidentiality. It is unclear how much of this could end up in the NHS data store, which is supposed to include ‘Covid-19 test result data from Public Health England’. In July, DHSC admitted no data protection impact assessment had been conducted before launching the service.

What does the public think?

Broadly, the public tends to trust the NHS and healthcare providers more than other types of organisations with their personal data. Greater openness is also likely to build trust. But there have been some more specific, recent polls about contact tracing.

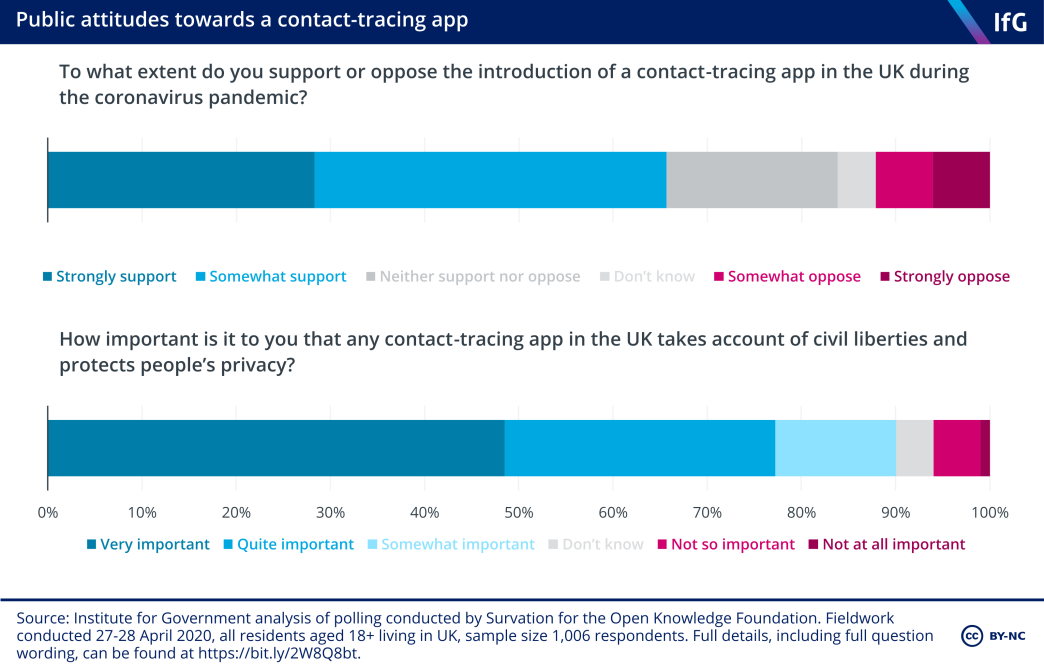

Polling for the Open Knowledge Foundation in April 2020 found around 65% of those polled supported the introduction of a contact tracing app. More than three-quarters thought it was ‘very’ or ‘quite’ important that any such app took account of civil liberties and protected people’s privacy (rising to nine in ten when ‘somewhat important’ was included). In June 2020, polling by Ipsos MORI for the Health Foundation found 62% of people would download the app, but this varied significantly by occupation, education and age.

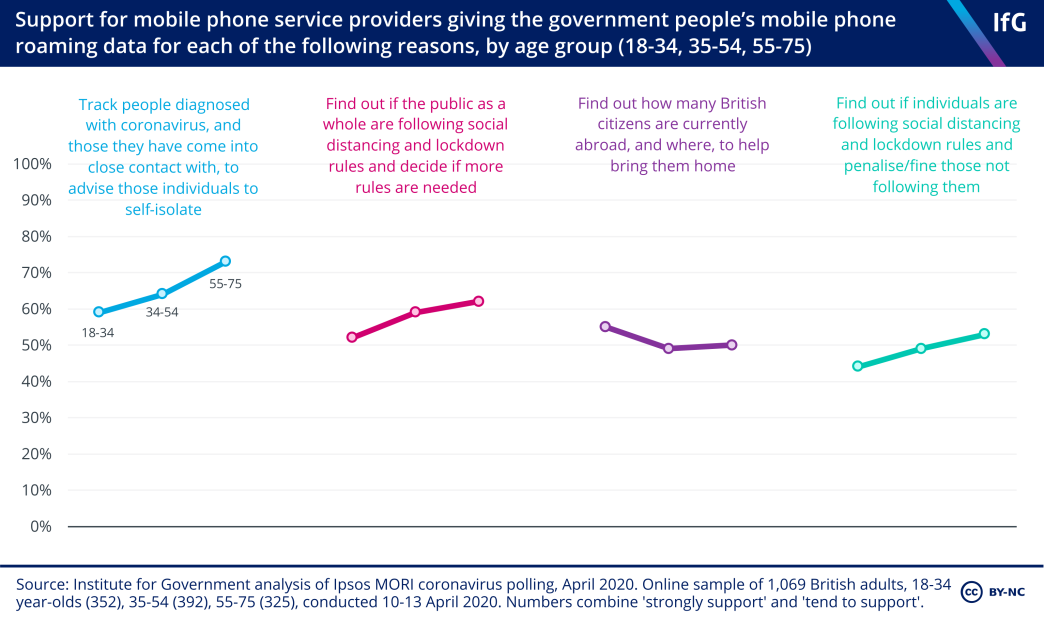

An Ipsos MORI poll (conducted in April 2020) found strong public support for mobile phone companies handing over data to the government to help find people who had come into contact with those suffering from coronavirus. Around half were supportive of data being handed over to find out if particular individuals were breaching social distancing guidelines or lockdown. Support for data being handed over tended to increase with age.

Other studies also suggest public support for contact tracing. Again, though, digital contact tracing has not yet been shown to have worked.

Timeline

See a more extensive timeline of data-related developments in the UK government’s coronavirus response – please add anything we’ve missed.

- Topic

- Coronavirus

- Keywords

- Data and digital Law Parliamentary scrutiny

- Publisher

- Institute for Government