Government use of personal data in the coronavirus response requires public debate and support

The government’s response to the coronavirus crisis makes an open discussion about its use of citizens’ data more urgent

The government’s response to the coronavirus crisis makes an open discussion about its use of citizens’ data more urgent, says Gavin Freeguard

Outbreaks and pandemics often focus attention on the conditions that helped them to spread. In the past, this has put sanitary conditions – overcrowding, water supply – under the spotlight, and that is happening again in the case of washing hands, wild animal markets and wearing masks. But in countries with well-developed public health systems, might subsequent scrutiny fall on disease surveillance? Could better use of data have helped us to track, and stop, the spread of coronavirus, especially since much of the technology now exists?

The government is already exploring options. Health secretary Matt Hancock has announced that the NHS is developing a contract tracing app – which has been rolled out in different varieties across the world – alerting those who could be infected, while three leading figures in NHSX – the NHS’s relatively new digital transformation unit – blogged about their work to build a data platform and data store to help coordinate national efforts.

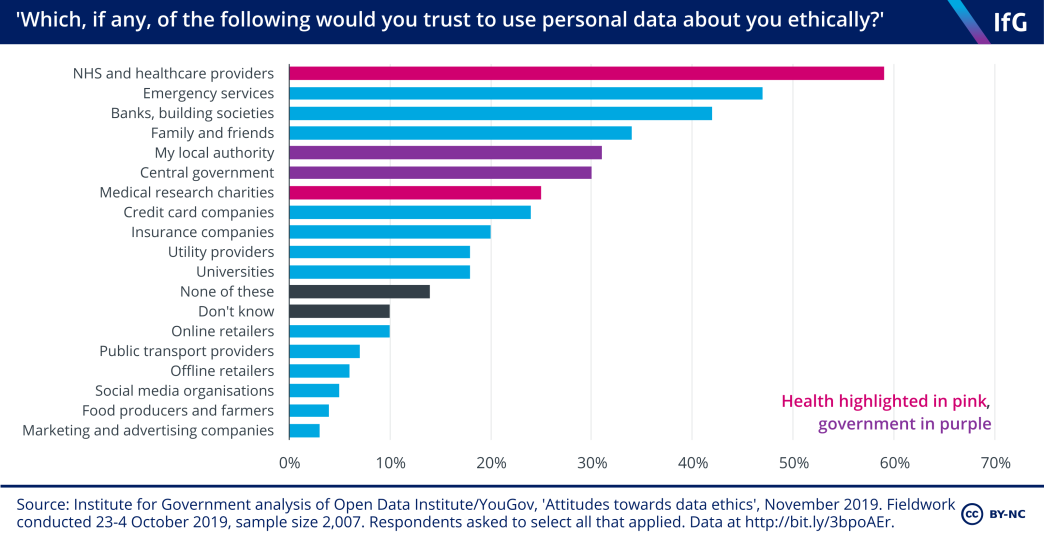

Better, more joined-up use of our personal data is not a panacea – the Ada Lovelace Institute has gone so far as to say ‘there is an absence of evidence to support the immediate national deployment’ of contact tracing apps’ – but it may be able to help track the spread and mitigate the effects of coronavirus. However, the use of personal data by government, not to mention tech giants and other private companies, inevitably raises tricky questions about privacy and to what level people are willing to have their personal data shared.

The NHS is already trusted by the public to use and share its data

‘Personal data’ covers a variety of types and forms of information. Sometimes it allows specific individuals to be identified easily; other times, it is aggregated and anonymised (although research has raised doubts about how far personal data can be completely anonymised). Some of it might be administrative data, logging our interactions with public services; sometimes it will be survey data which records our answers to specific questions; sometimes it can be much more invasive, such as using our phones to track our movements.

Openness is key to securing this public trust, and the NHS has so far been reasonably transparent about how it is using data during the crisis. However, the location data needed for contact tracing sits in a group of personal data that the public is more reticent about sharing – just 13% of people are comfortable with the sharing of behavioural data, which includes tracking someone’s location. And the government’s troubled care.data scheme, which closed in 2016 following years of controversy over the ethics and technicalities of data sharing, is a reminder that health data is a sensitive area.

The government has not done enough to explain how it uses our personal data

Last summer, leading civil society groups (including the Institute for Government) wrote to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport ahead of the government’s (still) forthcoming National Data Strategy. We said that great public benefit can come from the more joined-up use of data, but that this would only be possible with ‘with appropriate safeguards, transparency, mitigation of risks and public support’; government needs to ‘earn the public’s trust’ and have the debate about the appropriate use of citizens’ data ‘in public, with the public’.

But the public still doesn’t know that much about how personal data is shared and used across government and the public sector. What data is being shared, with whom and by whom? What are the processes, flows and levels of access? What is being shared with the private sector? What legal gateways are departments using? What ethical frameworks, such as the government’s data ethics framework or the ‘five safes’ framework for using sensitive data, are departments applying? Without the answers to these questions, it is difficult to answer even bigger ones: where is data sharing working well across government, how are departments successfully balancing ethics and effective use, and how can those principles and practices be embedded across government?

Matt Hancock’s proposed tracing app will be voluntary, with the government promising that ‘all data will be handled according to the highest ethical and security standards, and would only be used for NHS care and research, and we won’t hold it any longer than it’s needed.’ The source code will also be published as part of the government’s ‘commitment to transparency’. But if the use of personal data is to play a central role in the government’s response to coronavirus, then the government needs to provide greater transparency about how data is currently used and shared, greater honesty about the trade-offs between ethics and efficacy, and clear ways of bringing the public into the discussion. The dialogues being started by the National Data Guardian and others look like a promising start, but discussion will need to go beyond health and care data.

When the inquiries into coronavirus have been held, will we look back on an absence of contact tracking or health apps which record population health in the same way we now regard cramped tenements and poor sewage systems – or will the mere suggestion that this might be the retrospective view lead to changes that are far too sweeping? Improving people’s living conditions and sanitation was about creating a healthier society; so too will be balancing the risks and benefits of asking citizens to hand over their data.

- Supporting document

- gaps-govt-data-final.pdf (PDF, 200.68 KB)

- Topic

- Coronavirus

- Keywords

- Data and digital

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government