Outsourcing and privatisation

What is the difference between privatisation and outsourcing?

What is outsourcing?

Outsourcing is when companies, charities or other organisations run services on behalf of the government. These contracts are usually awarded following a competitive tendering process.

Examples of outsourced services include collecting household waste; cleaning schools, hospitals and government offices; providing IT services and support; managing prisons; and providing residential care to the elderly. Over £100 billion a year is spent on outsourcing by central and local government, and public bodies. 22 It is not possible to produce an exact figure for spend on outsourced services because the Treasury only publishes data which also includes spending on goods, such as paperclips or other equipment. In 2019/20, spending on both goods and services was £233bn. The National Audit Office has previously estimated that over half of this spending is accounted for by outsourced services. See Table 5.5 in HM Treasury, Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses 2019-20, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/901406/CCS207_CCS0620768248-001_PESA_ARA_Complete_E-L…; National Audit Office, The role of major contractors in the delivery of public services, 2013, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/10296-001-BOOK-ES.pdf

The rationale for outsourcing is that applying market mechanisms and private sector expertise to the work of government can reduce costs, raise quality and achieve wider benefits such as greater innovation and improved efficiency.

What is privatisation?

Privatisation is the sale of publicly owned assets to private investors. Investors take on responsibility for operating, managing and investing in the assets – and providing any services that derive from them in return for a fee from users. In the UK, the most well-known examples of privatisation have been utilities, such as energy, water and telecoms, and other assets such as rail and mail.

Early proponents of privatisation believed that creating markets would ensure services were efficiently produced and high quality, and the need for regulation would “wither away” as competition took hold. In practice this has not happened. These industries remain highly regulated – in several, regulators set the prices companies can charge and the amount they are expected to invest. 23 Johnson P, ‘It’s not obvious from the past that government can better run utilities’, Institute for Fiscal Studies, blog, 2 October 2017, www.ifs.org.uk/publications/9962

Opponents of the involvement of private companies in the health service often complain about “NHS privatisation”. This is the wrong term. NHS bodies contract private companies to deliver health services, often to help meet high demand, but NHS assets are not “sold off”.

Does this terminology really matter?

Yes. While they are often used interchangeably, outsourcing and privatisation are not the same thing. They have some similarities but also some big differences. The reasons why they have or have not worked are not necessarily the same.

Our research found that outsourcing has helped to drive improvements in efficiency and innovation in some areas, but there have been failures when government has not done enough due diligence on suppliers, been too focussed on price or allocated risks poorly.

Some dynamics are similar for privatisation. As with outsourcing, government has struggled to get companies to focus on broader goals rather than maximising profits. And as with outsourcing, asymmetric information (when the company has data government does not) has left service design and delivery vulnerable to ‘gaming’ – for instance private companies misrepresenting the quality of performance.

But unlike with outsourcing, failures to overcome these problems in privatised assets centre on the role of regulation. Government has often proved unwilling or unable to equip regulators with enough teeth to get companies to behave in certain ways. Despite regulators mandating low profit margins, for example, investors have managed to load companies with debt and extract large profits, particularly in the water sector. Another difference is around fees: there has also long been debate over how to balance keeping costs low for passengers and consumers against the need for long-term investment.

In several areas, variants and hybrid models have emerged. In rail, the track and the rolling stock were initially sold off to separate companies, but Network Rail, which manages the track, was later brought back under government control as an arms-length body of the Department for Transport (DfT). Train operators, which lease trains from rolling stock companies, are given contracts – or franchises – to operate routes over a specified period. 24 Butcher L, Railways rolling stock (trains), House of Commons Library, 2017, http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN03146/SN03146.pdf

Under Private Finance Initiative (PFI) contracts, outsourcers have built assets, such as prisons, and then operated them for an agreed contract period, typically 25–30 years. In most cases, these assets will return to public ownership when the contracts expire. 25 National Audit Office, Managing PFI assets and services as contracts end, 2018, www.nao.org.uk/report/managing-pfi-assets-and-services-as-contracts-end/; Panchamia N, Competition in prisons, Institute for Government, 2012, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/Prisons%20briefing%20final.pdf

Why are outsourcing and privatisation relevant now?

At the 2019 general election, Labour said it would return privatised utilities to public hands and “end all privatisation” (they meant outsourcing) in the NHS. In the 2020 leadership election, Sir Keir Starmer backed these policies – and, so far, as leader he remains committed to them.

Recent Conservative governments have also acknowledged that outsourcing and privatisation have not always worked as intended. For instance, the May government looked at government outsourcing in the wake of Carillion’s collapse and commissioned the Williams review of the structure of the rail industry.

Reassessments have continued under the Johnson administration, and some of the difficulties have become more acute due to the coronavirus pandemic. In June 2020, Robert Buckland, the justice secretary, decided to bring probation in England and Wales fully back in-house from June 2021, citing the need for greater “flexibility, control and resilience” to manage the impacts of the virus.

DfT has introduced a new franchising system for Britain’s rail providers: operators are paid a management fee, but government bears all cost and revenue risk. This is a short-term measure, but it appears likely to be similar to the system the Williams review, still yet to report, will recommend and may prove to be the government’s preferred longer-term option. 26 The Economist, ‘A bailout for Britain’s railways’, 21 March 2020, retrieved 22 March 2020, www.economist.com/ britain/2020/03/21/a-bailout-for-britains-railways

Debate about whether to return outsourced services and privatised utilities to public hands looks set to rumble on.

What if government does choose to take back control of services or assets?

An increasing number of local authorities and public bodies have already decided to bring outsourced services back in-house. For example, Hackney Council took over its waste collection in 2010 after two decades of contracting out, while the DVLA began running its own IT in 2014.

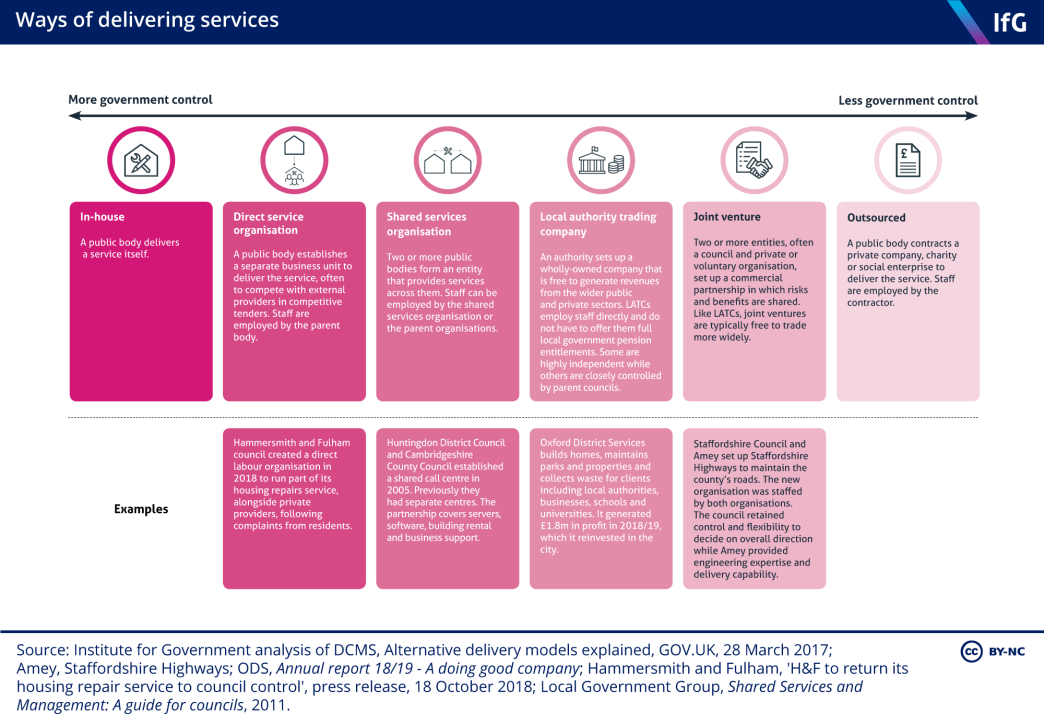

This is known as ‘insourcing’. As we set out in a recent report, insourcing can bring benefits including better quality and greater flexibility – but those choosing to do it need to ensure they understand the service, honestly assess whether they have the capability to deliver it better, and plan the transition carefully. There are several options between fully in-house and fully outsourced provision, such as joint ventures and trading companies (see chart). Each has pros and cons.

Renationalising privatised assets is an altogether different prospect. While there is little conclusive evidence that privatisation has improved quality or efficiency – some studies show improvements, others do not 27 Helm D, Thirty years after water privatisation – is the English model the envy of the world? Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol 36, no. 1, January 2020, www.dieterhelm.co.uk/assets/secure/documents/Thirty-years-after-water-privatisation-HELM.pdf – there is a debate to be had over whether renationalisation is now the best approach (we had that debate at the IfG during the 2019 election, available to watch on YouTube).

Broadly, advocates of renationalisation argue that changing ownership models is the best way to address problems such as poor quality, underinvestment and excessive executive pay. Critics argue that when utilities were previously nationalised it was not a great success and – in areas such as energy and water – better regulation would be a more effective solution.

A government that wanted to take back control of the operation of railways could simply wait for current franchises to end, but full renationalisation would mean buying back the rolling stock. In energy, water, mail and telecoms, government would also need to buy out the companies that own the underlying assets.

There is disagreement about how to price assets and companies fairly. Various methods have been floated, including market value plus or minus a certain amount or what is known is the Regulated Asset Base (RAB), which is based on what investors originally paid plus subsequent capital expenditure. At the 2019 election most discussion focussed on RAB, but there was discord over what premium should be paid on top of it for the risks investors have taken. 28 The Labour party said it would use RAB and others agreed using market value could be problematic with large fluctuations in share price. The CBI has used RAB plus 30% to estimate that Labour’s renationalisation plans would cost £196bn. But Dieter Helm, an expert on regulated utilities, argued this was “absurd” and around RAB plus 10% would be considered fair. BBC News, ‘Labour’s nationalisation price tag would start at £196bn, CBI says’, BBC News, 16 October 2019, www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-50036463; BBC Radio 4, ‘Nationalisation – how would it work?’ The Briefing Room, 27 September 2018, www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b0bkv1vd Any price would need to be seen as reasonable to avoid damaging investment in the wider economy.

- Topic

- Procurement Public services

- Keywords

- Outsourcing NHS

- Publisher

- Institute for Government