What is the European Investment Bank?

The European Investment Bank (EIB) is the European Union’s bank, owned by the EU member states – the bank’s only shareholders.

The EIB has an AAA credit rating[1] due to its wide portfolio of investments which spread risks. It can raise money at a cheaper rate than private debt and equity providers. As the EIB does not make commercial returns, it is a cheaper long-term source of finance than private equivalents.

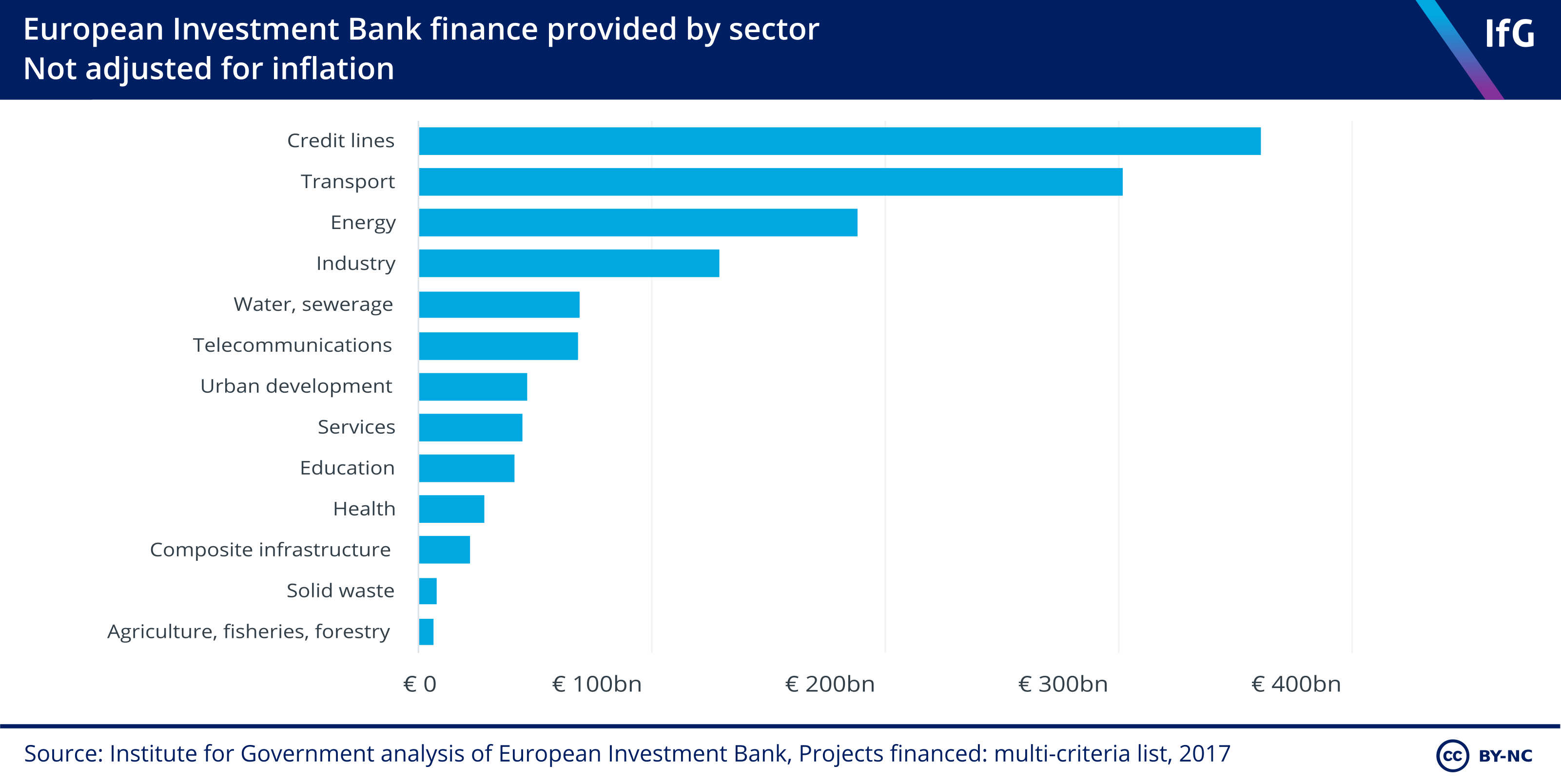

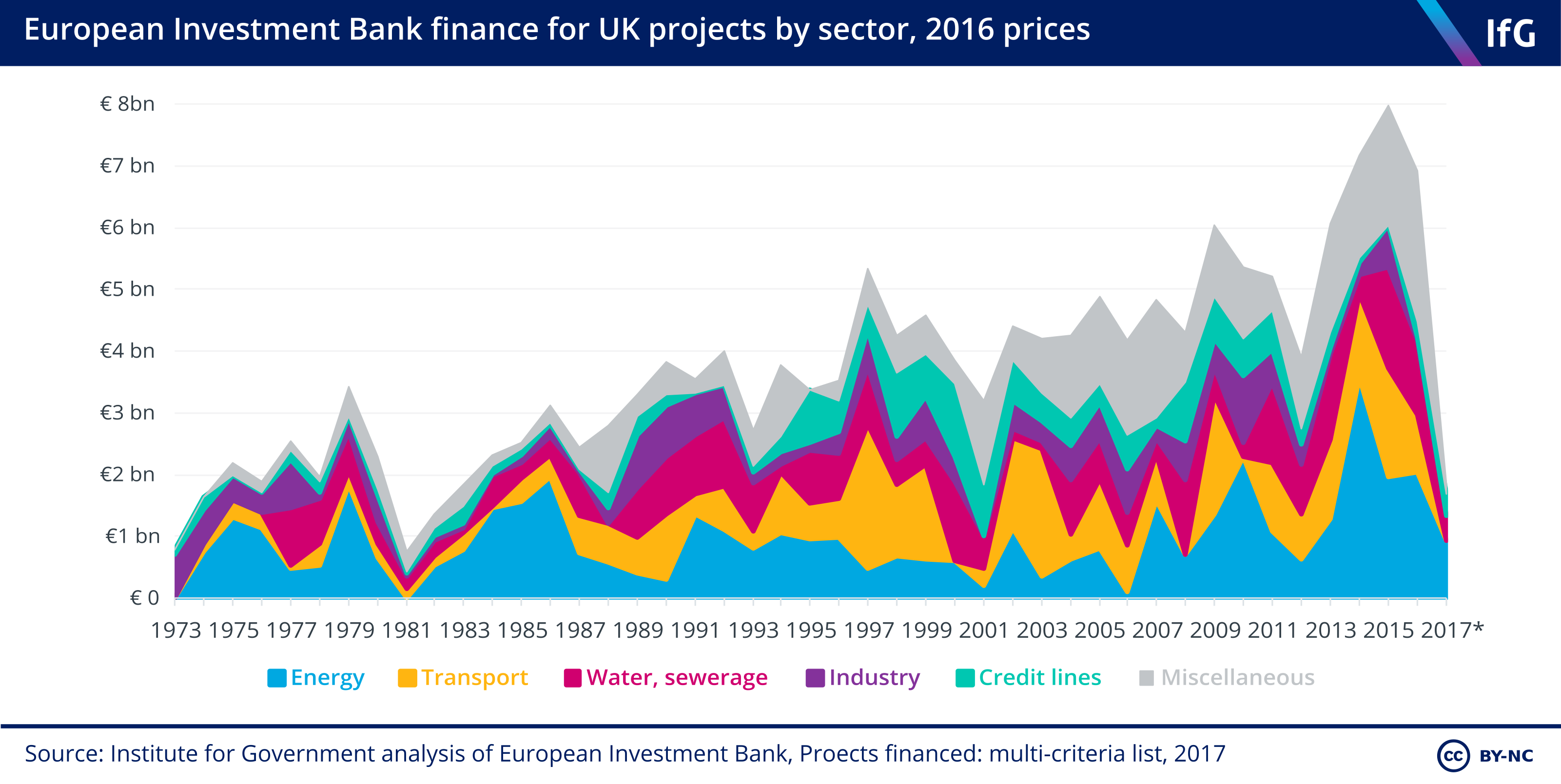

The EIB primarily invests in credit (where the EIB assumes financial institutions’ credit risk[2] to encourage them to lend), transport, and energy projects.

The EIB supports projects by investing directly, and by derisking them – guaranteeing that it will cover certain risks so that other financial institutions are more likely to invest. The EIB played this role[3] for the London Array offshore windfarm and Liverpool Port Extension, for example.

When investing, the EIB provides loans, guarantees, and equity to projects. The EIB also has a share[4] in the European Investment Fund (EIF), which invests in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

The EIBs derisking service advises governments on how to make projects ‘bankable’ i.e. how to design them so they are appealing to private investors. This can provide reassurance to private investors, encouraging private investment.

Where does the EIB invest?

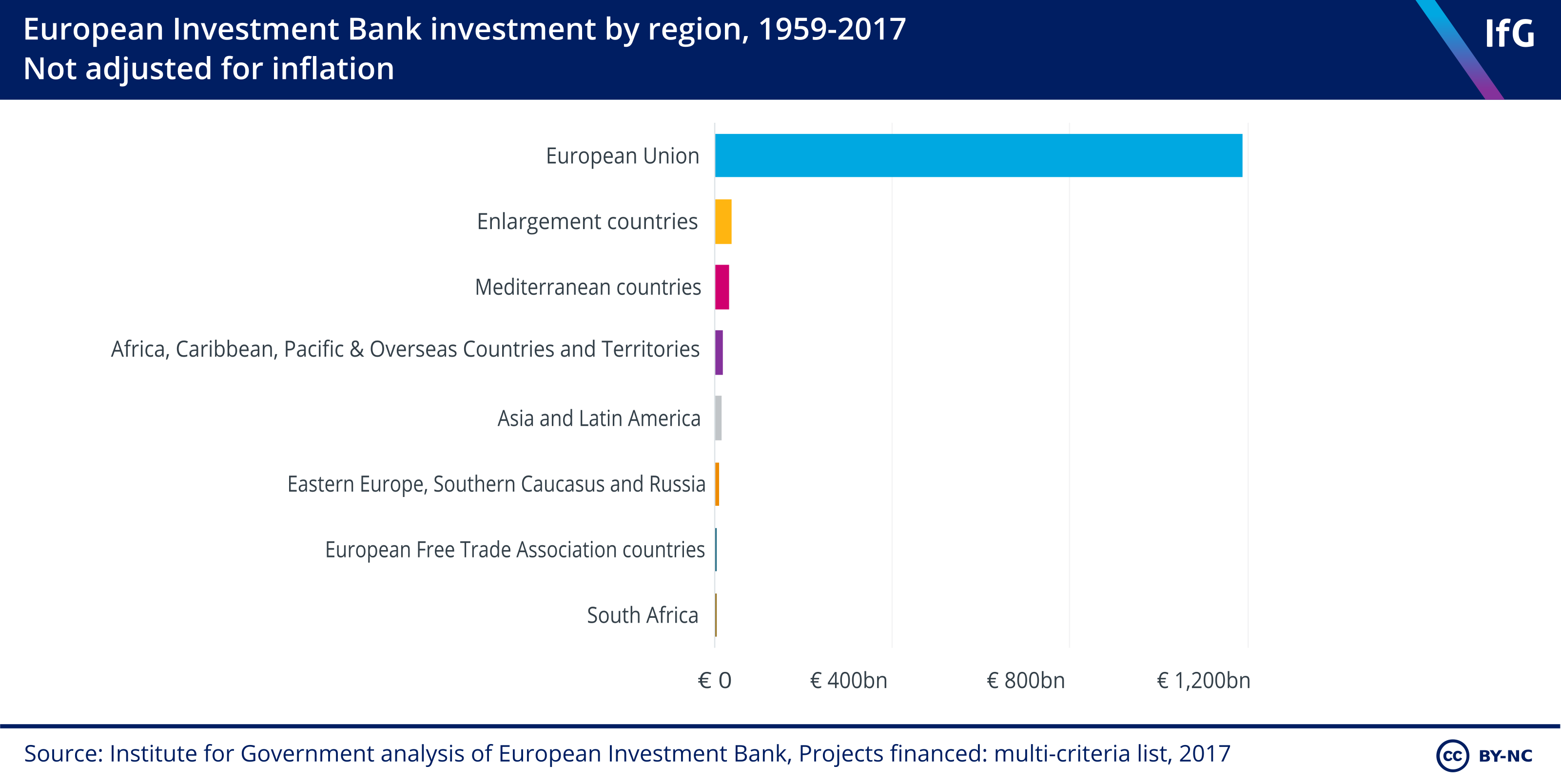

Most EIB investments have been in projects in EU countries, but 9% have been invested in projects in other regions.

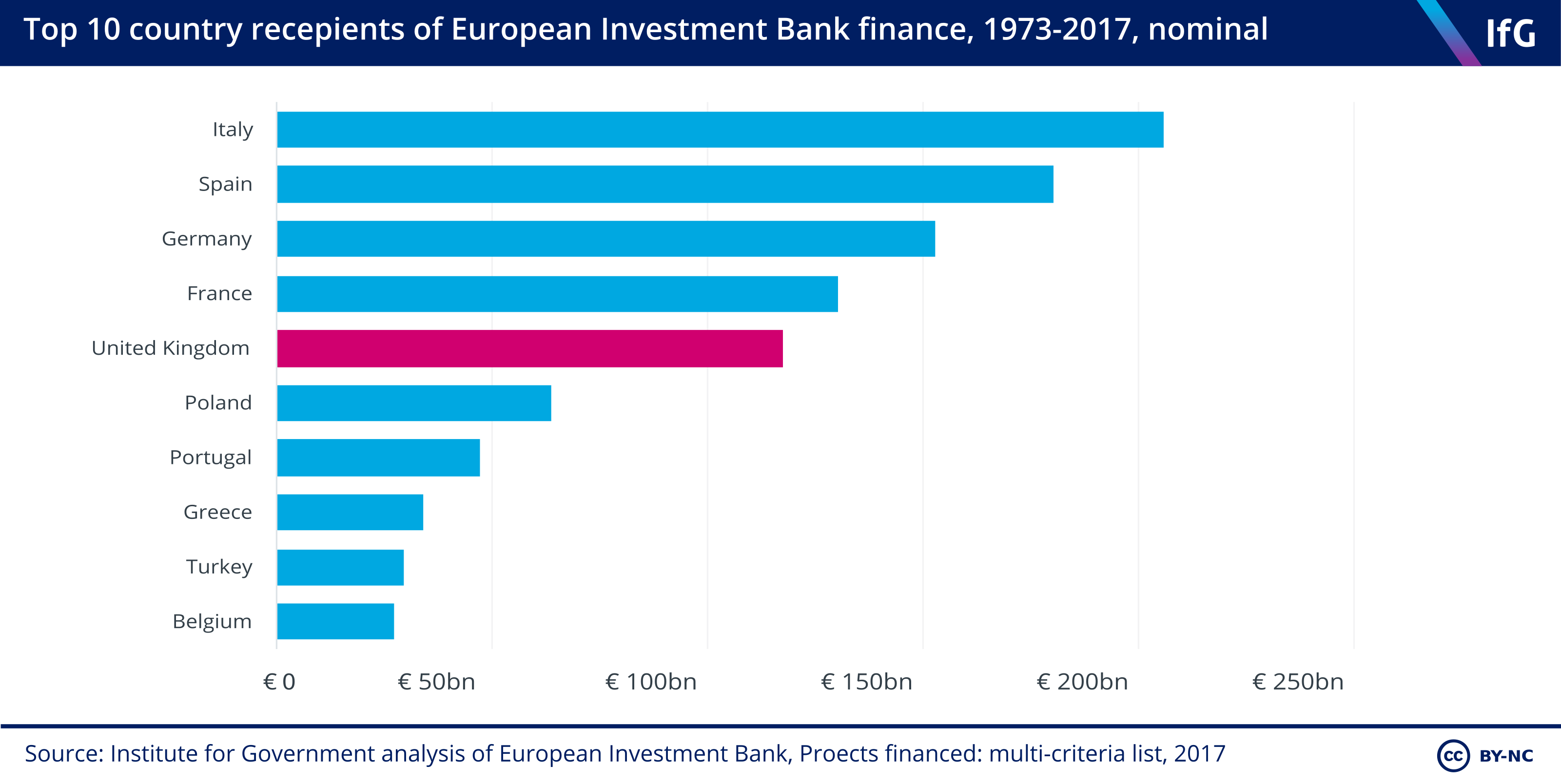

Compared to other countries, the UK has received the fifth most EIB investment.

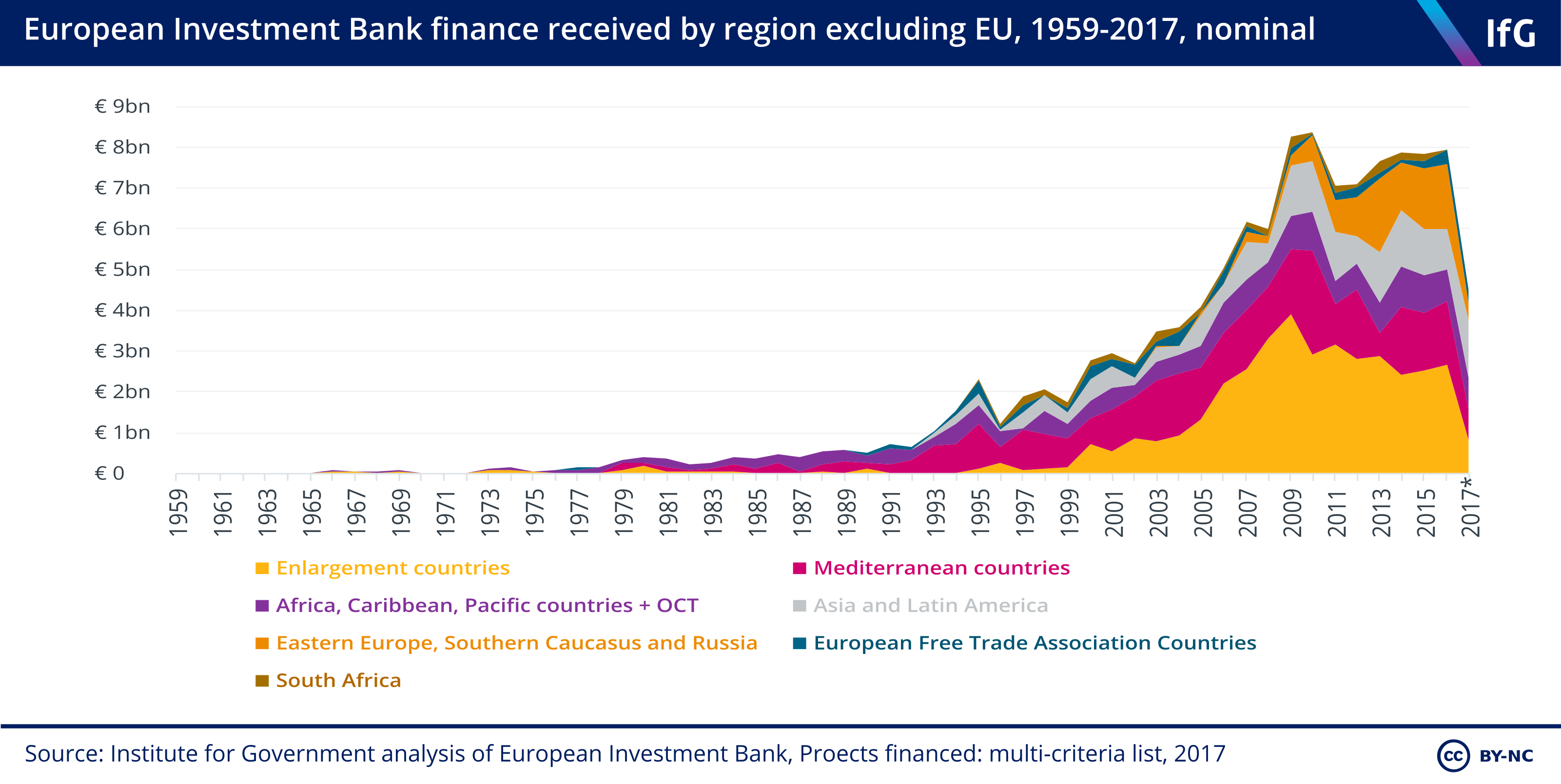

Outside the EU, the enlargement countries, EU applicants and potential EU applicants, have received the most EIB investment.

EIB investment outside the EU has also increased over the last 20 years. Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey have benefited most from this trend, but these investments remain modest in comparison to investment in EU member states.

Investments outside the EU focus on meeting EU aims, such as developing energy and transport networks in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries and promoting regional integration in Eastern Europe.

What projects has the EIB supported in the UK?

The EIB has invested primarily in UK energy, transport, and water projects. Recent projects include:

- guaranteeing €200m loans to northern SMEs

- a €220m loan for Merseytravel’s new trains

- a €900m loan for the Thames Tideway Tunnel.

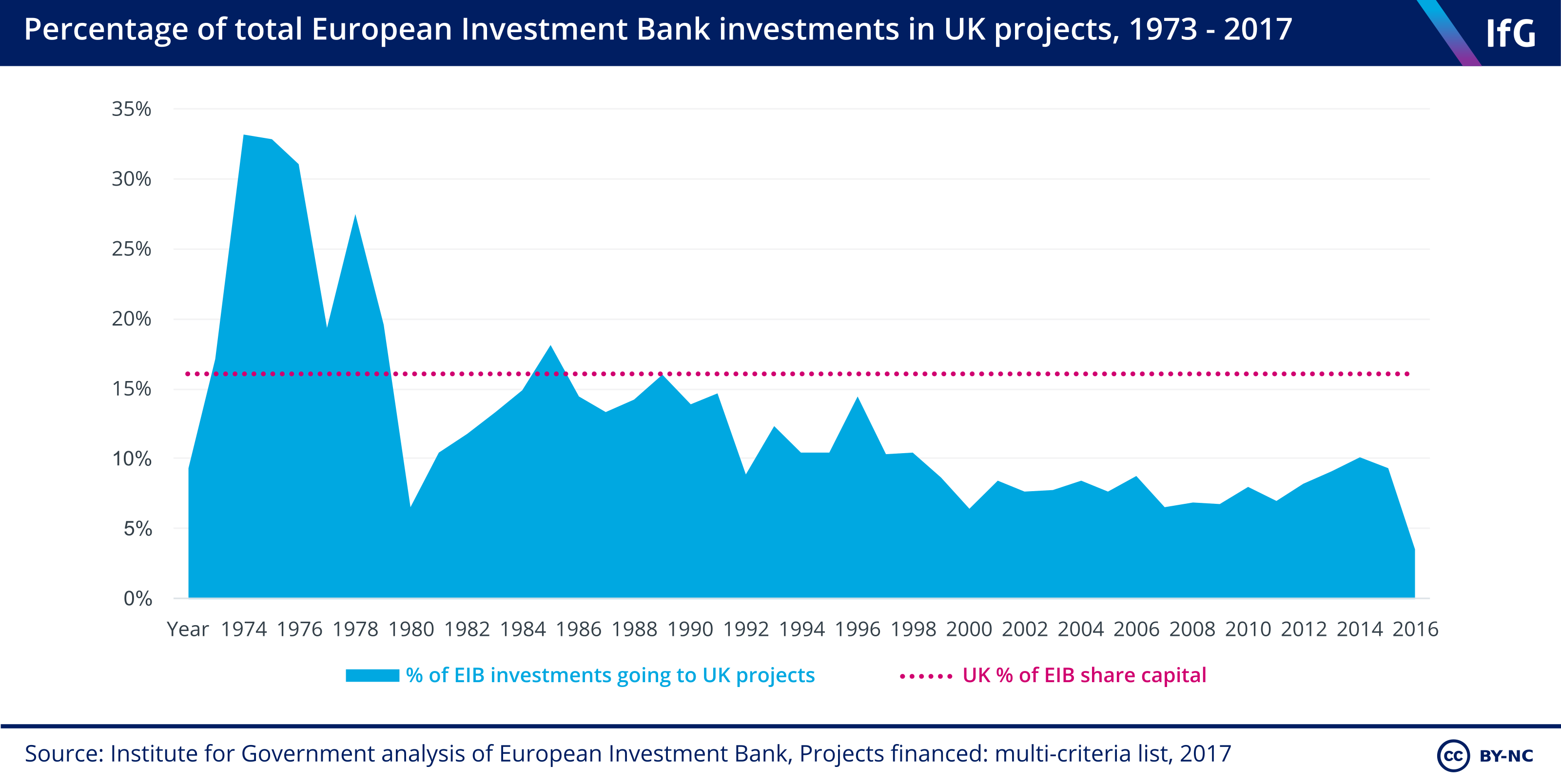

The EIB has invested €165bn in UK projects, just under 9% of its total investments between 1973 and 2017. The UK share of investment rose to 10% in 2015, after former chancellor George Osborne made increasing the share of investment the UK received a government priority.[5] It has since declined to 9% in 2016, and 4% in 2017.

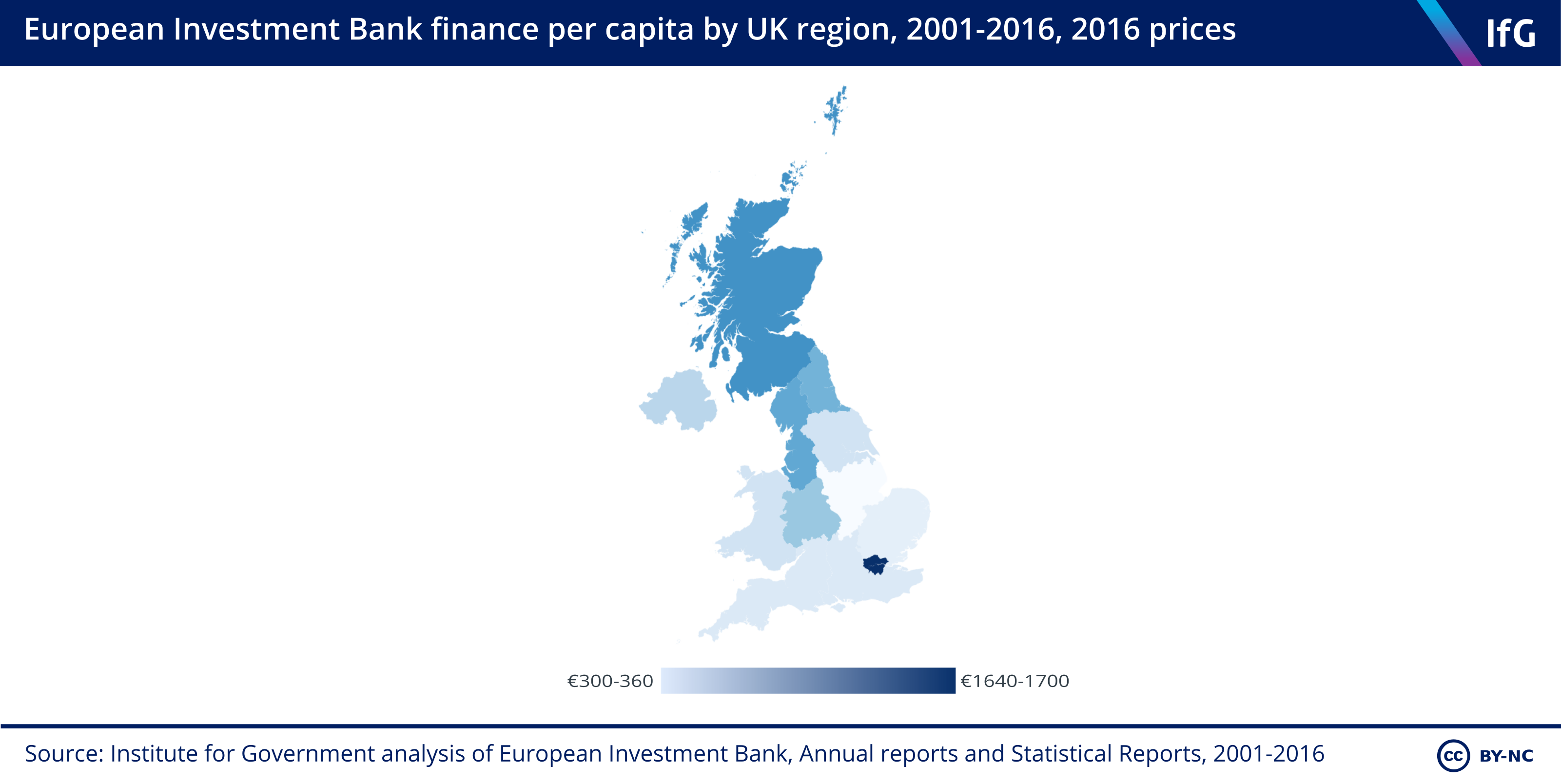

Within the UK, available data shows that the EIB has invested primarily in* London, Scotland, and the North West.

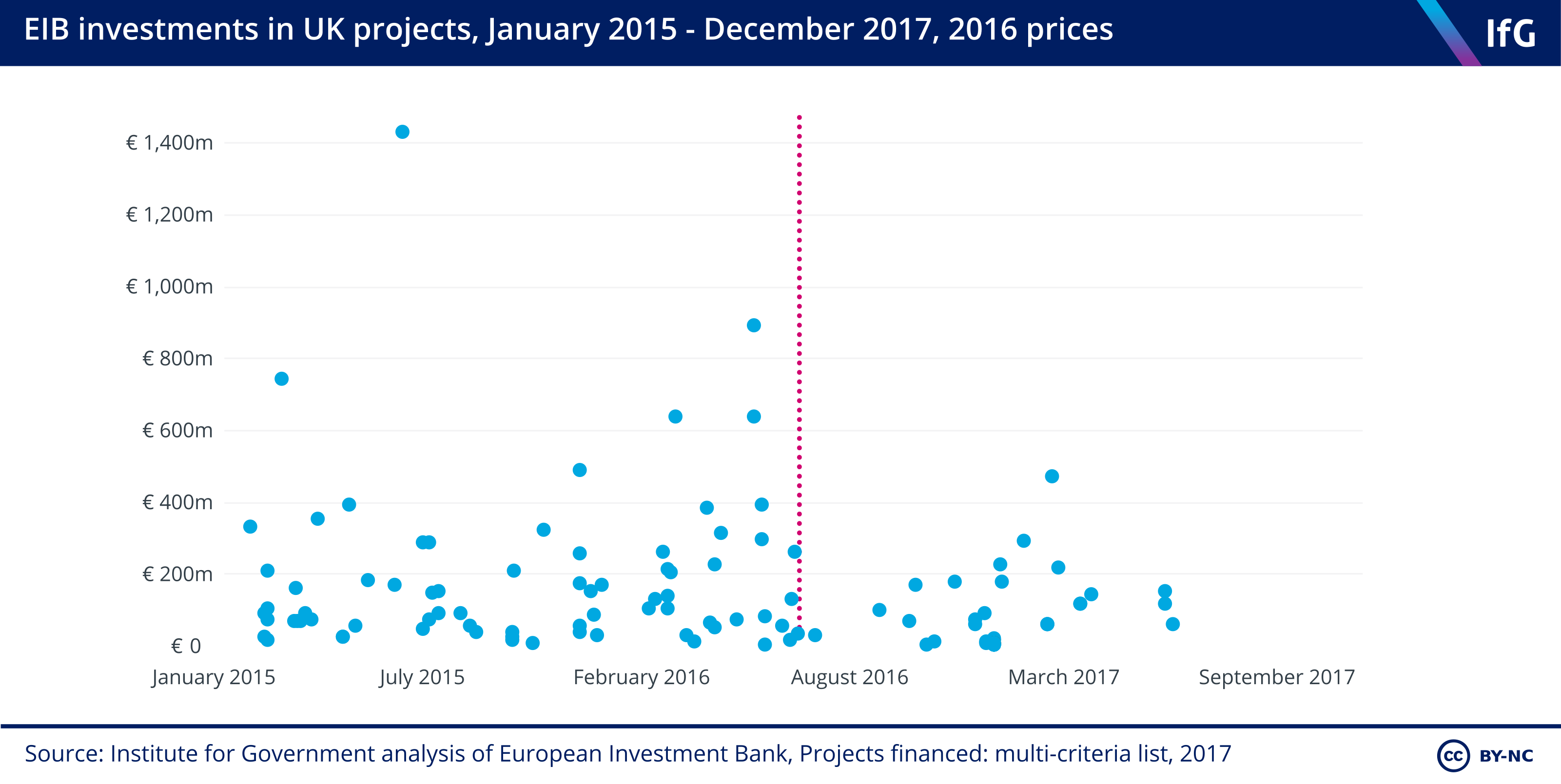

These regions have been most affected as the EIB made fewer loans to the UK after the 2016 EU referendum.

In the 18 months after the referendum, only 39 deals (collectively worth just under €3.1bn) have been finalised. In the 18 months before, there were 74 deals, (collectively worth over four times as much, €13.5bn).

UK projects remained eligible for EIB finance until the Withdrawal Agreement entered into force on 31 January 2020.

There was some controversy over lending in the interim period. The Guardian[6] and Business Insider[7] reported that the EIB and EIF put additional requirements on lending for UK projects after the government triggered Article 50 in March 2017. EIB officials, however, said lending to the UK declined because there were fewer projects requesting EIB finance. The EIB President, Werner Hoyer, argued that this was because of uncertainty about the UK’s future relationship with the EIB.

What has the UK contributed to the EIB?

After joining the EU, the UK became a member of the EIB with a 16% capital share.[8] The UK has contributed €3.5bn and has €35.4bn of ‘callable capital’.[9] ‘Callable capital’ is a contingent liability – money which the UK is obliged to pay if the EIB suffered losses it was unable to cover using its accumulated reserves.

The UK’s capital share has been a contentious issue, as the UK contributes a greater percentage of EIB capital than it receives as a percentage of EIB investment:

What does the Withdrawal Agreement say about the European Investment Bank?

The Withdrawal Agreement states that:

- The EIB will repay the UK’s paid-in capital in 12 annual installments, the first of which was paid in December 2019 (Article 150).

- The UK is still liable for its callable capital – money which the UK is obliged to pay if the EIB suffered losses it was unable to cover using its accumulated reserves – for projects approved before 31 January 2020. If these liabilities are triggered, the UK will have to pay the EIB on the same terms as other member states, which will be decided by the EIB board (Article 151).

- For projects which were approved before 31 January 2020, the existing UK–EIB relationship will stay in place. This preserves the EIB’s operating conditions to ensure that existing projects don’t face disruption because of the UK's withdrawal from the EU (Articles 124 and 137).

- After 31 January 2020, UK projects will not be eligible for EIB operations reserved for member states, and UK projects requesting loans or equity investments will be treated as “entities located outside the Union” (Article 151).

What has leaving the EIB meant?

As EIB finance is a cheaper source of finance than private equivalents, the UKs reduced access to EIB loans and equity investments will increase the cost of finance for projects.

If these higher costs are passed to taxpayers and consumers, then bills will increase – particularly in energy and water, where the EIB has lent extensively to UK projects. Water UK, the industry body for water companies, argues that consumers could face higher water bills[10] if regulated water companies lose access to EIB finance.

As there is some evidence that the EIB stimulated additional private investment by undertaking due diligence for and investing in novel and riskier projects (such as the Thames Tideway sewer tunnel), reduced access to EIB finance could reduce the number of UK projects in novel and risky sectors.

Some investors, however, argue that the EIB has crowded out private investment. Whether reduced access to EIB finance will affect private investment in novel and risky projects remains to be seen.

What does the Political Declaration say about the European Investment Bank?

The Political Declaration on the future UK–EU relationship, which sets the direction of the future relationship negotiations, notes the EIB as an area of shared interest for the UK and the EU, and notes “the United Kingdom's intention to explore options for a future relationship with the European Investment Bank (EIB) Group”.

This has been a common objective across the May and Johnson governments. During the May government, various ministers repeatedly said that they wanted access to EIB finance on better terms than non-EU member states. The former chancellor, Philip Hammond, said in June 2017 that “it may be beneficial to maintain a relationship”[11] in the future. Responding to a parliamentary question in September 2017, former Brexit secretary David Davis said that the UK “will be looking to maintain an ongoing relationship”.[12] The joint UK–EU report on phase one of Brexit talks in December 2017 noted that the UK wants to explore a “continuing arrangement between the UK and the EIB”.[13]

But maintaining a relationship will be difficult. If the UK were to remain a member, it would require the EU27 unanimously agreeing[14] to amend Article 308 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union which states that “members of the European Investment Bank shall be the Member States”.

Could the UK set up a domestic replacement?

Without a final deal on the EIB, several commentators have argued the UK should set up a domestic ‘Infrastructure Bank’ replacement. The National Infrastructure Commission, a non-departmental public body which advises the government on infrastructure investment, recommended that the government set up “a new, operationally independent, UK infrastructure finance institution”[15] by 2021, if the UK loses access to the EIB.

The government has not signalled it will do this. In the 2017 autumn budget, Philip Hammond promised that the government is “ready to step in to replace European Investment Fund lending if needed”,[16] though provided no details on this – and EIF lending is only part of the EIB’s overall investments.

The Johnson government ran a consultation on infrastructure finance between March and June 2019, and whether the UK needed to establish “a new, operationally independent, UK infrastructure finance institution”, but has yet to publish a response.

Any UK replacement would be resource intensive. Werner Hoyer, the president of the EIB, has said that it would take 10 years and significant upfront capital investment for the UK to set up a replacement with the equivalent capacity to make loans and equity investment.

*These figures only include regional investments. Multiregional, credit line, and global loans finance are not included. Between 2001 and 2016, region-specific investments accounted for 66% of the EIBs UK investments

- European Investment Bank, EIB Support to the Financial Sector Lines of Credit to Financial Intermediaries, November 2017, www.eib.org/attachments/country/acp_fs_lines_of_credit_to_financial_intermediaries_en.pdf

- European Investment Bank, Credit Rating, www.eib.org/en/investor_relations/rating/index.htm

- Vivid Economics, The role and impact of the EIB and GIB on UK infrastructure investment: Prepared for National Infrastructure Commission, May 2018, www.nic.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Vivid-Economics-Final-report-Analysis-of-EIB-and-GIB-projects-050718.pdf

- European Investment Fund, Register of Members, www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/register_shareholders.pdf

- HM Treasury and The Rt Hon George Osborne, New figures show record European Investment Bank investment in UK in 2015, GOV.UK, 14 January 2016, www.gov.uk/government/news/new-figures-show-record-european-investment-bank-investment-in-uk-in-2015

- The Guardian, UK infrastructure projects could be hit by European Investment Bank concerns, 15 May 2017, www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/may/15/uk-infrastructure-projects-could-be-hit-by-european-investment-bank-concerns

- Ghosh S, A £2 billion European investment fund has stopped giving money to UK tech startups because of Brexit, Business Insider, 19 May 2017, www.businessinsider.com/the-eif-has-frozen-funding-to-new-uk-vcs-and-cancelled-an-angel-investment-scheme-2017-5?r=UK

- European Investment Bank, Shareholders, www.eib.org/en/about/governance-and-structure/shareholders/index.htm

- European Investment Bank, 2016 Financial Report, March 2017, www.eib.org/attachments/general/reports/fr2016en.pdf

- Arqiva, Arqiva submission to National Infrastructure Committee’s Call for Evidence on 5G, www.nic.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Call-for-evidence-2.pdf#page=1708, p. 1708

- HM Treasury and The Rt Hon Philip Hammond, Mansion House 2017: Speech by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, speech, GOV.UK, 20 June 2017, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/mansion-house-2017-speech-by-the-chancellor-of-the-exchequer

- Parallel Parliament, Debates between Seema Malhotra and Mr David Davis, 2017, www.parallelparliament.co.uk/mp/Seema_Malhotra-Saluja/vs/David_Davis

- European Union and United Kingdom government, Joint report from the negotiators of the European Union and the United Kingdom Government on progress during phase 1 of negotiations under Article 50 TEU on the United Kingdom's orderly withdrawal from the European Union, 8 December 2017, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/joint_report.pdf

- House of Lords European Union Committee, Brexit and the EU budget: 15th Report of Session 2016–17, March 2017, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201617/ldselect/ldeucom/125/125.pdf#page=28, p. 28

- National Infrastructure Commission, National Infrastructure Assessment 2018, 10 July 2018, www.nic.org.uk/publications/national-infrastructure-assessment-2018/

- HM Treasury and The Rt Hon Philip Hammond, Autumn Budget 2017: Philip Hammond's speech, speech, GOV.UK, 22 November 2017, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/autumn-budget-2017-philip-hammonds-speech

- Topic

- Policy making Brexit

- Keywords

- Trade

- Publisher

- Institute for Government