Funding changes signal an end to the government’s ambitious social care reform package

Stuart Hoddinott says the government’s latest announcement is short-sighted, stores up problems, and leaves a key manifesto pledge unfulfilled.

For over 25 years, successive governments have discussed and then failed to reform adult social care. 18 The King's Fund, A short history of social care funding reform in England: 1997 to 2021, www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/short-history-social-care-funding So the announcement of two white papers in late 2021 by Boris Johnson’s government 19 Department of Health and Social Care, People at the Heart of Care: Adult Social Care Reform White Paper, December 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1061870/people-at-the-heart-of-care-asc-reform-access… 20 HM Government, Build Back Better: Our Plan for Health and Social Care, September 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1015736/Build_Back_Better-_Our_Plan_for_Health_and_So… gave those in the service hope that a government was finally serious about tackling this thorny issue. But decisions to first delay charging reforms and now shift funding away from important workforce initiatives shows that the government has given up on its manifesto commitment to implement social care reform that “stands the test of time”. 21 Conservative Party Manifesto 2019, www.conservatives.com/our-plan/conservative-party-manifesto-2019

The government’s approach to adult social care funding is short-sighted

The government’s announcement of how it intends to spend £2 billion of previously announced funding 22 Department of Health and Social Care, Adult social care reform - media fact sheet, blog, 4 April 2023, https://healthmedia.blog.gov.uk/2023/04/04/adult-social-care-reform-media-fact-sheet/ suggests that it has dropped many of its previous commitments. Making £250 million available for a range of workforce initiatives represents a 50% cut compared to its white paper pledge of £500 million, and there was no mention of the £300 million to “integrate housing into local health and care strategies” – another key element of its reform package – which we can therefore assume the government has also cut.

Reneging on these commitments will come at a cost. Capacity in adult social care is severely limited, with an ongoing workforce crisis being one of the key reasons for a deficit of supply – 10.9% of posts were vacant as of January this year, a larger proportion than in the NHS. Low pay compared to other sectors is one reason for poor retention of carers, but dissatisfaction with training opportunities and the lack of career progression also contributes to poor retention, two issues these reforms were intended to address.

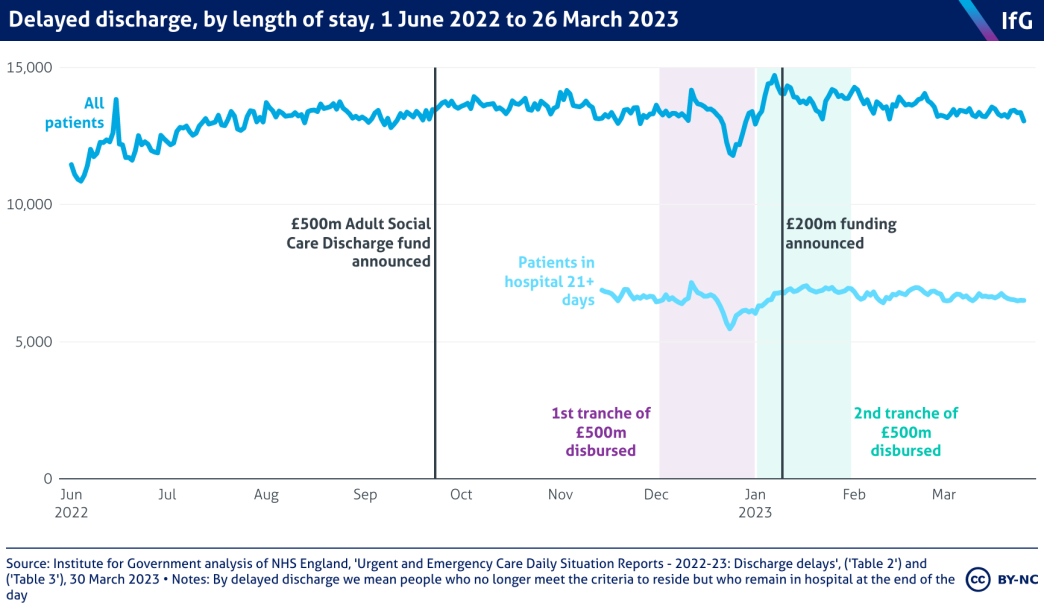

Not investing in better training, conditions and career progression now means that the government will have to spend more in the future to recruit staff in an emergency, as it did this past winter. But that approach is ineffective and represents poor value for money. Despite investing £700 million into the service to improve delayed discharge, the number of people who remain in hospital despite being eligible for discharge has hardly fallen.

While there is no correct level of funding for adult social care, the government should recognise that this decision will come with consequences.

Social care reform should focus on more than improving hospital discharge

While the government made cuts to social care workforce investment, it made clear that improving discharge out of hospital was a key priority. Its latest announcement detailed that £600 million of the £2 billion previously earmarked for investment in the service would instead be spent on “improving hospital discharge”, with £1.6 billion of the £8.1 billion allocated for the Better Care Fund in 2024 now designed to serve the same purpose.

But this suffers from the same problem as recent government announcements about the service; it casts adult social care as important only insofar as it supports the NHS. This approach directly contradicts what Sajid Javid claimed was the purpose of the government’s 2021 reform package, when he used the foreword to the People at the heart of care white paper to argue that the proposed reforms “offer people choice and control over the care they receive, […] promote independence and enable people to live well as part of a community, [and] enable [the workforce] to deliver the outstanding quality care they want to provide”. The latest announcement undermines almost all elements of that proclamation and instead treats adult social care as a pressure valve for hospitals.

It isn’t just a people-centred social care service that this announcement weakens, but also another key government priority. The government used the spring budget to announce childcare reforms that were intended, at least in part, to increase workforce participation. In the same way that many parents are discouraged from re-joining the workforce due to a lack of affordable childcare, poor social care provision shifts the burden of care onto working age adults who cannot afford to fund care for their loved ones, and who then leave the workforce.

Boris Johnson, Sajid Javid and Rishi Sunak on a visit to Westport Care Home in east London in 2021.

This announcement means that social care will remain un-reformed for this parliament

This announcement also signals that the government is effectively shunting reform into the next parliament, abandoning one of its key manifesto promises and ditching Boris Johnson’s commitment that social care would be reformed “once and for all”. Even if charging reform is implemented in October 2025 as currently planned, it will still be 14 years since Andrew Dilnot first made these recommendations, and more than a quarter of a century since Tony Blair’s government established the Royal Commission on Long Term Care in 1997. 24 The King's Fund, A short history of social care funding reform in England: 1997 to 2021, www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/short-history-social-care-funding Users and carers have been let down yet again.

Implementation of these reforms in 2025 is far from guaranteed, with further delay likely. If Labour wins the next election, then it is likely to substantially amend the Conservatives’ reforms, meaning another long wait before social care receives the reform it so badly needs.

Public finances will not make life easy for whichever party wins that election. Spending plans beyond 2024/25 are currently very tight, with the government pencilling in annual spending increases of approximately 1% at last year’s autumn statement. Most of those increases will go to areas of protected spending – the NHS, schools, and overseas aid – which will leave very little available for social care.

This policy instability from the centre has implications for the entire sector. Recent work from the IfG shows that uncertainty about policy implementation and funding decisions discourages investment by both local authorities and providers in the service, which in turn contributes to worsening outcomes. Making commitments and abiding by them is one of the most important steps the government could make to encourage other stakeholders to invest in the service.

The government will be criticised for this announcement, but the biggest impact will be felt by the people who use the service. Saying that social care is in urgent need of reform is easy, but delivering that pledge has once again proved to be beyond ministers.

- Keywords

- Social care Health NHS Public spending Public sector Budget

- Political party

- Conservative

- Position

- Health secretary Prime minister

- Administration

- Johnson government Sunak government

- Department

- Department of Health and Social Care

- Public figures

- Boris Johnson Sajid Javid Rishi Sunak Steve Barclay

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government