Five things we learnt from Jeremy Hunt's 2022 autumn statement

The IfG team give their verdict on the chancellor's autumn statement and what it means for government borrowing, households and public services.

On 17 November 2022 the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, delivered his autumn statement. Alongside it, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the independent fiscal watchdog, published its updated economic and fiscal forecasts – forecasts chancellors have since 2010 used to ‘cost’ their plans, but which Hunt’s predecessor Kwasi Kwarteng declined to ask for on launching his ill-fated ‘mini budget’ in September.

Hunt confirmed the reversal of many of Kwarteng’s announcements. But he also had to go further to restore fiscal sustainability and credibility in response to official forecasts expected to paint a notably bleaker picture than when last conducted in March.

These are the five things the Institute for Government learnt from the statement.

1. How tough will next year be?

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects real household disposable income (a measure of living standards) to fall by 7.1% between 2021/22 and 2023/24 – compared with a 1.4% fall over the same period predicted in its March forecast. If realised, this would be the sharpest fall in this measure of income since at least the second world war.

Given the weaker outlook for the economy, the OBR has revised up its forecast for unemployment, which is expected to peak at 4.9% in 2024, compared to a peak of 4.2% in 2023 in the March forecast.

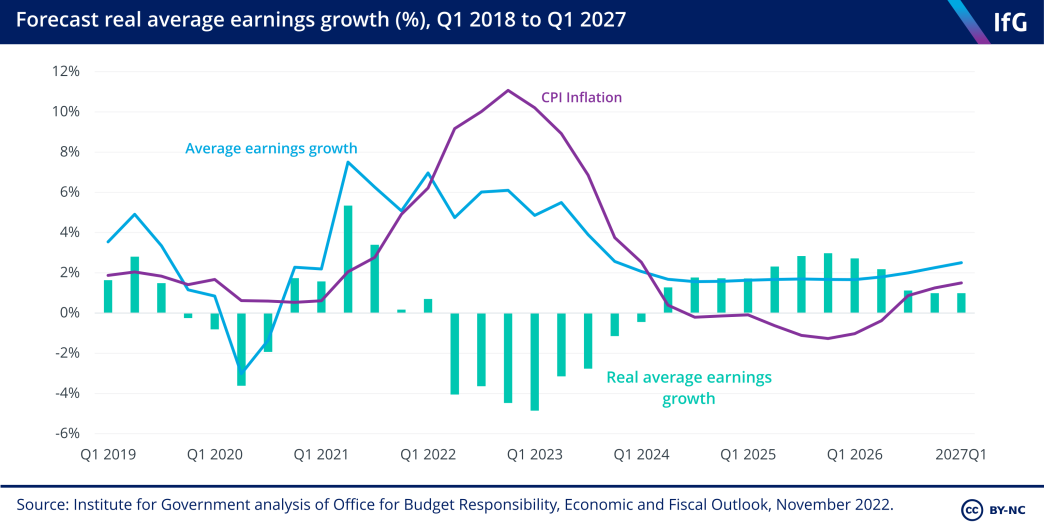

The outlook has also worsened for those who manage to remain in work. Although nominal average earnings are expected to grow by more in 2023 than expected in March (4.3% compared to 2.8%), the forecast for inflation has worsened. The OBR now expects inflation to peak at 11.1%, rather than at 8.7% in the final three months of 2022. The increase in prices relative to March far outstrips the rise in wages, meaning that the OBR expects real (that is, adjusted for inflation) wages to fall by 2.2% in 2023.

What matters for household incomes is the combination of changes to wages and changes to personal taxes and benefits. Since March, the government has announced substantial additional support for energy bills, totalling £58bn in the current fiscal year and £25bn in 2023/24. This includes the one-off payments to vulnerable groups announced in May by the then chancellor Rishi Sunak, which were extended today by Jeremy Hunt, and the “Energy Price Guarantee”. The latter will now cap energy prices so that the typical household will pay the equivalent of up to £2,500 per year between October 2022 and March 2023, rising to £3,000 between April and August 2023.

The combination of changes in economic conditions, new support for energy bills, and other changes to tax and welfare is what is driving the 7.1% fall in real household disposable income this year and next.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects real household disposable income (a measure of living standards) to fall by 7.1% between 2021/22 and 2023/24.

2. How much worse is the economic and fiscal outlook?

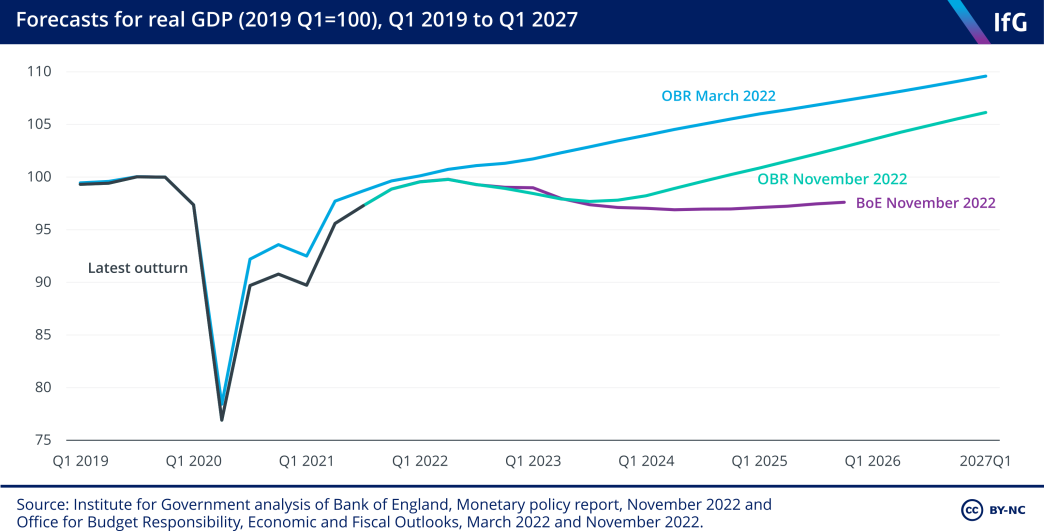

The economic outlook has worsened substantially since the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) published its last forecast in March. Back then the OBR predicted that economic growth would slow next year, after the post-pandemic rebound in 2021 and 2022, but continue to be around 2% a year. But since then it has become clear that the UK is headed for recession, as the global energy crisis has intensified, inflation has risen faster and the Bank of England has hiked interest rates more quickly than previously anticipated.

The new OBR forecast is for the economy to contract by 1.4% in 2023, before growing sluggishly in 2024 and then more strongly in 2025 and 2026. This is a substantially weaker path for growth than the OBR expected in March. It puts the OBR roughly in the middle of the pack among UK economic forecasters but is notably more optimistic than the growth forecast published by the Bank of England just two weeks ago.

This weaker economic outlook translates into weaker public finances. Tax revenues are expected to come in less strongly as the economy is weaker, and the government will come under pressure to spend more on debt interest payments and benefits in response to higher interest rates and higher inflation. In the absence of any policy action in the autumn statement, higher debt interest costs would have added £52.7bn a year to borrowing by 2027/28. Other adverse changes to the economic forecast would have added a further £29.3bn, giving a total of £82.1bn higher annual borrowing by the end of the forecast horizon.

Jeremy Hunt responded to this downgrade to the medium-term economic and fiscal picture by announcing tax rises and spending cuts. Taken together, all the policy changes that have been announced since March will save the exchequer £38.8bn a year in the medium term.

The net effect is to leave the government on course to borrow 2.4% of national income in the medium term. This compares to a plan for medium-term borrowing of just 1.1% of national income back in March.

The Bank of England has hiked interest rates more quickly than previously anticipated.

3. What are the government’s objectives for debt and borrowing?

Jeremy Hunt today announced the latest set of fiscal rules, the ninth set of rules in the last 15 years. As has been the case previously, a new set of rules was adopted largely because the old ones were due to be missed – this time because of the large deterioration in the economy.

While Rishi Sunak’s primary fiscal rule required that debt be on course to fall in the third year of the forecast (2025/26 for the autumn statement), Hunt’s rule only requires debt be on course to fall in the fifth year (2027/28). This represents a notable loosening of the rules and allows the government to reduce the deficit more slowly than would otherwise have been the case. The government is on course to meet this target, though only with around £9 billion of headroom to spare – compared to the roughly £30 billion of headroom that Sunak had against his rule in March.

Hunt’s other rule is that borrowing should be less than 3% of GDP in the fifth year of the forecast. It is welcome that the government has an additional rule on borrowing as well as debt, because debt rules can be easy to manipulate. However, while recent governments have had a rule requiring that the government be on course to run a current budget surplus (borrowing only to invest), Hunt’s rule makes no such distinction between day-to-day and capital spending.

There is a good rationale for a current budget rule – in other words, one that specifically restricts the level of day-to-day spending relative to government revenues, while allowing additional borrowing for investment. This is because capital spending (such as investment in infrastructure) is more likely than day-to-day spending to benefit future generations who will be required to pay back any borrowing.

Historically, investment spending has been an easy target for governments seeking spending cuts as it is politically easier in the short term, with costs only emerging in the long term. Hunt has followed this course – achieving 40% of his spending cuts in the autumn statement by holding capital spending fixed in cash terms from 2025, albeit investment spending (at 2.2% of national income by 2027/28) will still be relatively high as a share of national income by historical UK standards.

Overall, in historical terms these are a permissive set of rules. In only six previous forecasts has the Office for Budget Responsibility projected a current budget deficit in the fifth year of the forecast horizon.

Despite the permissive nature of the current rules, the scale of the economic downgrade since March means that meeting these rules has nonetheless required tricky decisions on tax and spending. And Hunt has left only a small margin for error against the rules, meaning any further deterioration of the forecast could necessitate additional action next year.

4. Is the government improving the tax system?

The autumn statement announced 27 new tax measures, to add to the 12 that had already been announced since the spring statement in March. Together they amount to a net tax rise of £8.6bn a year by 2027/28, with large tax cuts (for example, the cut to National Insurance rates and increases in the annual investment allowance) more than offset by even larger tax increases (for example, the windfall tax on energy producers and freezes or cuts to a range of tax thresholds and allowances).

But it is hard to discern much in the way of a vision for the tax system that underpins these changes. The policies chosen seem to have been mainly because they are likely to be easy to sell to the public. Freezing tax thresholds and allowances, for example, raise revenues by stealth – gradually dragging a greater share of incomes into higher tax brackets without anyone seeing a fall in their nominal income. As we have argued previously, it can make sense for governments to take these opportunities.

But the current crisis could also have been an opportunity for more radical reform of long-standing problems in the UK tax system. As former Treasury permanent secretary Lord Macpherson put it, “if you can persuade the British people that we’re in really tough times and that difficult decisions are being made, you can do quite big things”. Chancellor Jeremy Hunt chose not to attempt this approach. With less than four weeks between Rishi Sunak becoming prime minister and the autumn statement, and with the last government’s efforts at radical tax changes having led to acute economic turmoil, it is perhaps understandable that Hunt and Sunak decided to take a more cautious approach this week. But we might have hoped for a clearer statement of this chancellor’s objectives for the tax system, alongside consultations on difficult areas, to provide a blueprint for a more strategic approach to tax policy going forwards.

There was some excitement in the run up to the autumn statement at rumours that the chancellor was set to announce a new road tax for electric vehicles (EVs). The question of how to tax electric vehicles has long hung over the Treasury as the UK transitions to net zero. Fuel duties and vehicle excise duties together generate over £30bn a year for the exchequer. But these revenues are being undermined and will ultimately disappear as drivers shift to electric vehicles, which avoid paying these taxes. The Treasury needs to develop a strategy for recouping these revenues – and for tackling the external costs caused by motorists (whether fossil fuelled or electric) from congestion. But the measure announced in the autumn statement – an extension of vehicle excise duty to EVs from April 2025 – failed to live up to the hype.

Energy profits levy will increase from 25 to 35% from 1 January and there will be a new temporary 45% levy on electricity generators.

5. What are the plans for spending on public services?

The government’s plans for spending on public services were not quite as tight as some predicted, but they still point to a difficult few years ahead.

The chancellor provided some extra money for some public services over the next two years (within the current spending review period). Health, social care and education received a combined additional £9 billion in day-to-day funding in 2024/25, while the decision to allow councils to raise council tax without a local referendum is likely to provide further additional funding for social care. This was funded by a combination of scrapping the planned increase in overseas aid spending and extra borrowing. This spending will help those services to meet increasing demands and to start to tackle Covid-induced backlogs, and those services will now see higher real-terms spending settlements than originally planned last October, but it is unlikely to be sufficient to solve those problems given their scale.

Apart from those additions, spending settlements are more or less unchanged in cash terms since they were announced last October. This is despite higher than expected public sector pay awards. Pay awards this year averaged around 5%, compared with expectations of around 2–3% when the budgets were set, and the Bank of England expects private sector pay to increase by a similar amount again next year. Given how difficult public services are already finding it to recruit and retain enough staff, and the scale of public sector strike action on the horizon, a key difficulty for public services for the next two years will be whether to increase pay (and so have less money to spend elsewhere) or hold down pay (and struggle to recruit and retain workers and risk widespread strike disruption). We will shortly be publishing further analysis on what these spending plans mean for different public services.

Beyond the spending review period, further restraint is planned with day-to-day spending increasing by only 1% per year in real terms. Only two spending review periods since 2002 – George Osborne’s in 2010 and 2015 – had tighter plans. After accounting for likely increases in health, defence and overseas aid spending, other departments will see real spending cuts after 2024/25.

These spending plans would be very difficult to deliver and would not be consistent with improving public services. They would imply most departments having lower spending in real terms in 2027/28 than they did 17 years earlier. It seems likely that whichever government wins the next election would top up these plans before they come into force. This is what happened before the 2015, 2020 and 2021 spending reviews.

If the government does want to make public services more efficient, one option we highlighted in a recent paper was to invest more in buildings and equipment to enable sustainable long-term savings. It is welcome that the government has retained relatively generous capital spending plans for the remainder of the spending review period. It is then set to be frozen in cash terms beyond the next election, which would mean little substantial new investment forthcoming for, among other things, hospital, school and prison buildings. But, as with day-to-day spending, it is possible that whichever government is in power beyond the next election will provide more money for these areas.

Health, social care and education received a combined additional £9 billion in day-to-day funding in 2024/25.

- Keywords

- Budget Cost of living Austerity Energy Health Social care Education Schools NHS Criminal justice Tax

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Jeremy Hunt Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government