Northern Ireland Protocol Bill

What does the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill say – and what does it mean?

Why has the government introduced the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill?

The Ireland/Northern Ireland protocol was agreed in October 2019 as part of the UK–EU Withdrawal Agreement with the aim of preventing a hard border on the island of Ireland once the UK left the EU single market. It requires Northern Ireland to align with the EU in certain areas like customs, goods regulation, VAT, state aid and rules on agri-food, allowing it to maintain frictionless access to the EU market and prevent checks on goods moving between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. This all meant it introduces barriers to trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Since mid-2020, the UK government has been arguing that the protocol creates unacceptable barriers to trade within the UK internal market, and has been seeking changes – detailed in a command paper published in July 2021. The EU rejected these demands, and as renegotiation of the protocol but in October, the EU it published its own proposals in response, to reduce but not remove the level of checks and controls within the framework of the existing legal text. The UK argued these did not go far enough.

The UK and the EU entered into discussions on changes to the protocol in the Joint Committee – the body responsible for overseeing the implementation of the protocol – but the two sides have been unable to come to an agreement and there have been no meetings since February. In February 2022, the DUP first minister Paul Givan, resigned, citing the party’s objections to the protocol. The DUP and has refused to re-establish an executive in Northern Ireland following the May’s assembly election.

In June, the UK government introduced the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill to the House of Commons to unilaterally override parts of the protocol. It also published a document setting out the government’s legal justification for the bill,[1] and its proposed arrangements proposals for replacing the existing arrangements.[2]

What’s in the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill?

Clauses |

What does it say? |

What does it mean? |

|---|---|---|

|

Effect of the protocol in UK law Clauses 2 and 3 |

These clauses remove the effect of “excluded provisions” of the Northern Ireland protocol in UK law and connected parts of the Withdrawal Agreement. The excluded provisions are specified in later parts of the bill. |

Although the UK is unable to unilaterally change the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement, the bill would remove the direct effect of parts of the agreement in domestic law. This would prevent it from having supremacy over UK law, as required by article 4 of the Withdrawal Agreement, allowing the UK to override parts of the protocol contrary to the terms of the treaty itself.[3] This would mean that the UK authorities, including the UK parliament, ministers and civil servants and the devolved governments, will no longer have to comply with or enforce parts of the Northern Ireland protocol. |

|

Goods: movements and customs Clause 4–6 |

Clause 4 removes the requirement for Northern Ireland to apply EU law on customs and goods regulation for ‘qualifying movements of UK or non-EU destinated goods’. The clause sets out a list of factors that could be used to determine whether goods should qualify, such as purpose, nature and manner of the movement. The bill gives ministers the power to make provision for the meaning of ‘UK or non-EU goods’ and defines qualifying movements as movements into Northern Ireland from other parts of the UK, or outside the EU. Clauses 5 and 6 give ministers powers to implement a new regime for the movement of goods between GB and NI. |

This clause would allow the UK government to implement its proposed ‘green lane/red lane’ system, in which regulatory checks and controls would not be required on goods moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland and staying there, but would still be required on goods destined for the Republic of Ireland and the rest of the EU. The government says this system will be underpinned by a trusted trader scheme, financial penalties for non-compliance and data-sharing. However, there is little detail provided as to how this would work in practice. Although the clause lists the factors minister may take into account when determining which goods should qualify for green lane access including, for example, to allow non-commercial goods to enter through the green lane, it gives ministers broad powers to determine, and implement, the detail of the scheme with scope for only limited parliamentary oversight. |

|

Regulation of goods Clauses 7–11 |

These clauses provide for a dual regulatory regime, allowing companies to choose whether to comply with UK or EU law, when supplying goods to Northern Ireland. This applies to any requirements related to the regulation of goods (set out in clause 10) including rules related to the sale and marketing of goods, packaging, licencing, testing and transport. The bill disapplies EU law so far as is necessary to facilitate the dual regulatory regime and gives ministers broad powers to implement it, as well as powers to turn the law on and off for a certain class of goods. |

The UK government argues this is necessary to prevent businesses trading solely within the UK from having to comply with two regulatory regimes and to minimise barriers within the internal market. Goods sold in Northern Ireland could be marked with CE and UKCA markings (demonstrating compliance with EU and UK product regulations respectively), and agri-food would be able to move GB–NI through a trusted trader scheme – although there may still be some limited checks on live animals. Some businesses in Northern Ireland, particularly in the agri-food sector, have warned that these arrangements could make cross-border trade on the island of Ireland more difficult. For example, the dairy industry has raised concerns that if the grain fed to dairy cows in Northern Ireland meets UK but not EU standards, NI farmers may not be able to sell their milk in the EU.[4] |

|

Subsidy control Clause 12 |

Clause 12 removes the effect of article 10 of the protocol on state aid, and gives ministers the power to make provision in relation to state aid in Northern Ireland. | This would remove Northern Ireland from the EU’s state aid regime, and bring it fully under the UK’s subsidy control regime. |

|

Implementation, application, supervision and enforcement Clause 13 |

Clause 13 removes the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice in the UK in relation to the Northern Ireland protocol and related provisions in the Withdrawal Agreement. It also removes the rights of EU representatives to oversee the application of EU law under the protocol, and creates a power for minister to make regulations in this area to facilitate other information or data sharing. |

The UK government says this clause is necessary to end the implementation and enforcement of EU law in UK law. It removes the rights of EU officials to be present during border checks and inspections on goods entering Northern Ireland in UK law, and will means the UK will not recognise infringement proceedings brought against the UK for non-compliance with EU law. |

|

Provisions of the protocol etc applying to other exclusions Clause 14 |

Clause 14 disapplies parts of the protocol and withdrawal agreement that relate to other “excluded provisions”, including the responsibility of UK authorities to implement EU law, for the courts to interpret legislation in accordance with EU case law, and parts of the dispute resolution mechanism. | This clause will remove the requirement for UK authorities – including officials – to comply with the parts of the protocol that have been disapplied. It also suggests that the UK will not participate in the UK–EU dispute resolution procedure in relation to non-compliance with the parts of the protocol the UK has disapplied. |

|

Excluded protocol provisions: changes and exceptions Clauses 15 and 16 |

Clause 15 creates a broad power for ministers to disapply other parts of the protocol or the withdrawal agreement (apart from articles of the protocol on individual rights, the common travel area and North–South cooperation) through secondary legislation, if necessary, for a range of ‘permitted purposes’ including social and economic stability, the effective flow of goods within the UK, and safeguarding biosecurity. Clause 16 allows ministers to make new law if they consider ‘appropriate’ through secondary legislation in connection with disapplied parts of the treaties. |

This power would allow ministers to disapply other parts of the protocol in future (other than specified parts) and make regulations for new arrangements through secondary legislation with limited parliamentary oversight. Although this is primarily presented as tidying up power, it is exceptionally broad, potentially giving ministers significant power, with little parliamentary oversight. |

|

VAT and excise duty Clause 17 |

Clause 17 gives the minister the power to make new provisions on VAT and excise duty including to eliminate or avoid any differences between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. | This clause is designed to address concerns that some tax measures announced by the Treasury – such as VAT cuts on solar panels and heat pumps – could not automatically apply to Northern Ireland due to the protocol. The protocol provides such issues to be considered in the Joint Committee but this would allow the UK to make provision unilaterally. |

|

Other ministerial powers Clauses 18 and 19 |

Clause 18 permits ministers to “engage in conduct” in relation to matters dealt with in the protocol if the minister “considers it appropriate to do so.” Clause 19 gives ministers powers to implement any UK-EU agreement on the Northern Ireland protocol through secondary legislation. |

These broad powers allow ministers to conduct ‘sub legislative activity’ such as issuing guidance. The Hansard Society has raised concerns that this could also be extended to other forms of activity. Clause 19 would remove the need for further primary legislation if an agreement with the EU is reached. |

|

The European Court of Justice Clause 20 |

This clause states that UK courts are not bound by decisions of the ECJ on matters related to the protocol, and cannot refer matters to the ECJ. It contains a power for the minister to make provision to allow the courts to refer a question of interpretation to the ECJ where necessary. |

Ending the role of the European Court of Justice has been a key priority for the UK throughout the Brexit process. However, it has been a key red line for the EU, who insist on a role for the ECJ where EU law applies. The UK will still apply EU law in some cases, for example for ‘red lane’ goods entering Northern Ireland and destined for the EU, but the bill will mean the ECJ will not have a role in overseeing the application of this law in the UK, and the UK courts will only be able to refer questions of interpretation. |

|

Final provisions Clauses 21–26 |

Regulations made under the Act may do anything that can be done by an Act of Parliament, including making provisions that are incompatible with the protocol or repealing or suspending other legislation giving effect to the protocol. Regulations are also able to amend the Act itself. But regulations may not be used to introduce border infrastructure of checks on controls on the island of Ireland. Regulations are subject to the negative procedure, unless they amend an Act of Parliament or make a retrospective provision, which are subject to the draft affirmative procedure, or made affirmative if urgent. Powers on tax or customs may only be exercised by the Treasury of HMRC. |

The bill contains broad powers, known as ‘Henry VIII powers’ that allow ministers to amend primary legislation using secondary legislation, which receives far less scrutiny. Regulations made in these circumstances will require a vote on the floor of both Houses to be approved, however, other secondary legislation will become law by default unless MPs or Peers find the time to object to them, which in practice can be a challenge. This means that ministers will be able to make changes both to the implementation of the protocol and the Act itself with very limited parliamentary scrutiny. |

Does the bill break international law?

The UK government has said that the bill does not break international law. Alongside the bill it published a summary of the government’s legal position, arguing that the legislation can be justified under the “doctrine of necessity” which allows a state to disregard parts of its international obligations in order to ‘safeguard an essential interest’.[5] The government argues:

“...the strain that the arrangements under the Protocol are placing on institutions in Northern Ireland, and more generally on socio-political conditions, has reached the point where the Government has no other way of safeguarding the essential interests at stake than through the adoption of the legislative solution that is being proposed”.[6]

However, there have been reports that the government’s own legal advisors have raised concerns about the strength of the government’s argument; suggesting that it would be ‘very difficult’ for the government to ‘credibly’ argue that there was no alternative to disapplying the protocol. A number of respected lawyers have also cast doubt on the government’s argument. Sir Jonathan Jones, the former head of the government’s legal department, described the statement as ‘hopeless’, and giving no evidence as to how the legal test has met, or why other lesser measures, such as the safeguarding measures in the protocol under Article 16, haven’t been met.[7]

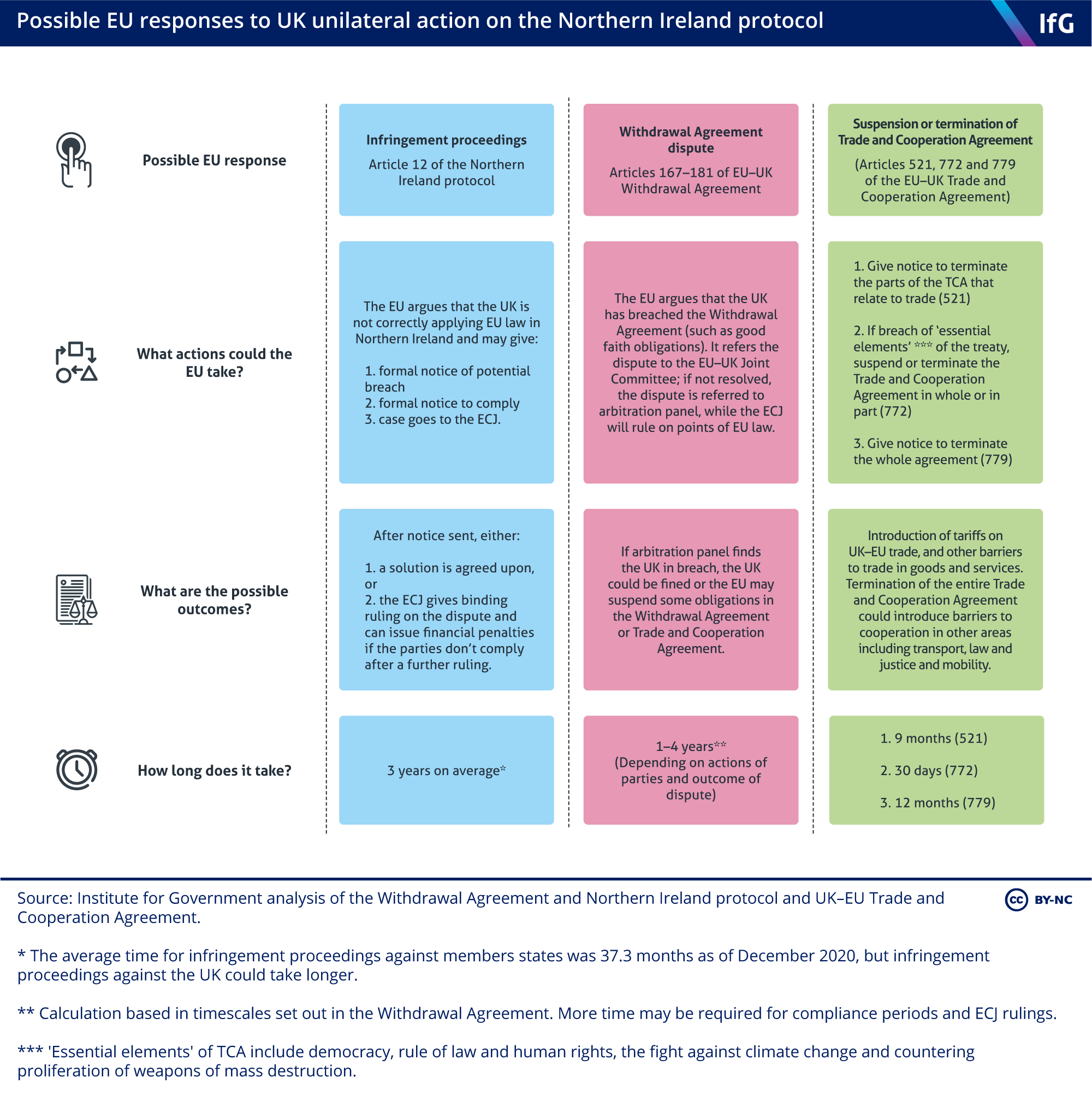

How might the EU respond?

Following the publication of the bill, the vice-president of the European Commission Maroš Šefčovič reiterated that the EU would not renegotiate the protocol. The EU has a number of legal routes to respond to unilateral action that it considers breaches the Withdrawal Agreement, as set out in the graphic below – although the effectiveness of some of these may be limited by the arrangements in the bill itself.

The vice-president said that the EU response would be ‘proportionate’ but also reiterated the EU position that “the conclusion of the Withdrawal Agreement was a pre-condition for the negotiation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement.”[8]

As a first step, the Commission has resumed infringement proceedings against the UK for earlier breaches of EU law.[9]

- www.gov.uk/government/publications/northern-ireland-protocol-bill-uk-government-legal-position

- www.gov.uk/government/publications/northern-ireland-protocol-the-uks-solution

- https://publiclawforeveryone.com/2022/06/13/the-northern-ireland-protocol-bill/

- www.rte.ie/news/ireland/2022/0608/1303686-ni-milk-protocol/

- www.gov.uk/government/publications/northern-ireland-protocol-bill-uk-government-legal-position/northern-ireland-protocol-bill-uk-government-legal-pos…

- www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/concerns-raised-at-top-of-government-over-legality-of-northern-ireland-protocol-bill

- https://twitter.com/SirJJQC/status/1536417826034130945?s=20&t=jF3UO0maaO2DBJLGaPCfwQ

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_22_3698

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_3676

- Topic

- Brexit Devolution

- Keywords

- Northern Ireland protocol

- Publisher

- Institute for Government