The government must step up its support for people told to self-isolate

Inadequate financial support for self-isolation could yet undermine the UK’s path out of the crisis

Even with progress on vaccinations, inadequate financial support for self-isolation could yet undermine the UK’s path out of the crisis, argues Tom Sasse

At the Covid-19 operations committee last week, health secretary Matt Hancock reportedly made the case for increasing statutory sick pay.[1] This puts him in line with many scientists and economists, who have long called weak support for those self-isolating a fatal flaw in efforts to control transmission.[2] But it pits him against the Treasury, which opposes what could be an expensive change.

With 25 million vaccinated, it would be easy to think (despite some bumpiness in supply) that we are close to being out of the woods. But the next phase, as we release restrictions and a large amount of the population remains unvaccinated, will be crucial. Even with the progress we have made, scientific advisers warn of a possible third wave.

Particularly in the coming months, any viable exit strategy will rely not only on vaccinations – but on being able to get those who catch Covid to isolate. But the data shows many are still not doing so because they lack support. If the Treasury continues to paper over these cracks, it risks doing much greater harm to the UK’s economic recovery – and people’s health.

There are still too many people with Covid not self-isolating

We do not have a perfect picture of people’s behaviour – there is not a continuous data series on compliance with self-isolation requests and naturally there are some issues with self-reporting. But the data we do have suggests that it has been, and remains, a big problem.

In August, a King’s College London study of over 30,000 people found only 18% of people with Covid-19 symptoms were self-isolating.[3] In September, the government’s expert advisers on behaviour, SPI-B, said that it was likely that full self-isolation rates were “very low”, particularly among the young and the poor.[4]

This January, UCL’s Covid social study reported that 30% of people asked to self-isolate did so for five days or less – rather than the full 10 days.[5] In February, Dido Harding, the chair of NHS Test and Trace, was forced to admit to the Health and Social Care Select Committee that by a rough estimate 20,000 people a day were not fully isolating when asked to do so.[6]

This compares poorly with other countries. Many have set a target of at least 80% compliance.[7] While data is limited and studies use a range of methodologies, evidence from South Korea and New York found compliance of 99% and 98% respectively.[8] Compliance in Germany has also been high.[9] Australia reported 93% compliance during the whole swine flu pandemic.[10]

Inadequate financial support is undermining compliance

There are many reasons why people may not self-isolate, but studies suggest the biggest ones are weak financial and practical support.[11]

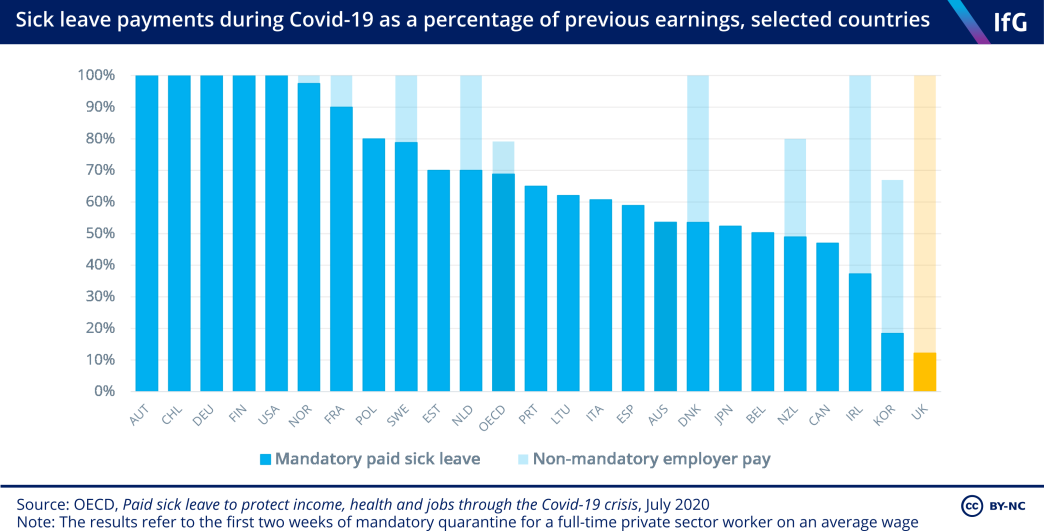

The UK has the lowest level of statutory sick pay in the OECD.

In Germany and the US, mandatory sick pay replaces all of the employees’ earnings for the first two weeks of absence due to Covid. In France, it is 90% for an average earner. In the UK, it is only around 10%, with employees entitled to just £94.25 per week.

Other European countries have different welfare models, and many UK employers top up statutory sick pay. But firms employing around a quarter of the UK workforce do not – and these workers are concentrated in the low-paid, customer-facing occupations most at risk of infection.[12] Two million of the lowest earners are excluded from receiving sick pay altogether.

People can access other support through the benefits system, such as Employment and Support Allowance. But this can be slow and bureaucratic – and overall support for those who cannot work due to illness in the UK is low.[13]

The UK also decided not follow China, Japan, South Korea, Germany and US cities like New York in providing accommodation to make it easier for people to self-isolate.

A recent report in the Financial Times from three east London boroughs illustrated how these factors come together to boost transmission. A shopkeeper tells the reporter:

“A lot of minicab and Uber drivers came to see me. They showed classic symptoms of the virus, but they kept saying things like: ‘Just give me something for the sore throat, cough syrup or something’. I told them time and again to get a Covid test, but they just did not want to get a test or go to the doctor because they knew they could not afford to isolate.” [14]

The shopkeeper goes on to contract Covid, take it home to a multi-generational household and infect both his elderly parents and his sister, before being able to find somewhere else to isolate.

The government’s attempted fixes have not worked

The government has made some sensible tweaks: in March 2020, the Treasury changed statutory sick pay to allow people to receive pay from the first rather than the fourth day of illness.

But its attempts to address the deeper problems have failed. In September, it introduced a new flagship scheme, administered by councils, that allows people to apply for a one-off payment of £500. To be eligible, they must prove they have been asked to self-isolate; and that they have a job, are unable to work from home, and will lose income from self-isolating, or that they are in receipt of certain means-tested benefits.[15]

But in the scheme’s first seven months, less than 75,000 people in England received payments and two thirds of applicants were rejected.[16] In part this was due to a failure to produce evidence, often due to delays with contact tracing. These low success rates no doubt dissuaded other people, if they had heard of the scheme at all, from taking a test and risking losing their income.

Given daily cases reached 50,000 in January, it is clear that this scheme has not worked as officials had hoped. It has proved too slow, bureaucratic and meagre to make a difference. Yet the government appears set on persisting with it. Buried in the budget documents was a pledge to continue with £20m per month of discretionary funding, though no recognition of the policy’s flaws, much less a plan for tackling them. Matt Hancock’s leaked intervention suggests his department, which is responsible for monitoring the scheme’s effectiveness, thinks this is a big problem.

Fixing self-isolation needs to be part of the exit strategy

The Treasury is understandably concerned about repairing the public finances and wary of measures that are inefficient or threaten to become permanent. It already rebuffed Hancock’s advances in January, when he called for the £500 payment to be paid to everyone asked to self-isolate – a move that would have been poorly targeted.

But continuing with the faltering approach to self-isolation as we unlock is incredibly risky. According to Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer, the government’s modelling still suggests there is likely to be third wave that could cause 30,000 deaths. He explained large outbreaks are still possible when only a small proportion of the population remains vulnerable because “that still equates to a very large number of people”. The more transmissible variant dominant in the UK and variable levels of vaccine uptake across the country create uncertainty about the threshold at which we might reach herd immunity.

It seems clear that isolating cases will be a part of the strategy in the months ahead. So the chancellor should look again at increasing sick pay – or alternatively consider extending the Job Retention Scheme to those who are ill and need to self-isolate. The Resolution Foundation estimates using the latter approach to raise the generosity of support to cover 80% of previous earnings for those self-isolating could cost £314m per month if the scheme was used widely.[17] Not insignificant, but small compared with the cost of lockdowns. The cost could be much less if outbreaks (and the number of people asked to isolate) are kept small, or with a smaller increase in generosity.

These approaches would have the benefit of being a much bigger signal – if people don’t believe their lost wages will be covered, small administrative tweaks are unlikely to work – while also being better targeted at those who feel unable to isolate because of the financial hardship it might cause. They would also be speedier than the current payment. These reasons probably explain why this is the route most OECD countries have used to expand support for those self-isolating during Covid. [18]

The Treasury need not see this as locking itself into unwanted future changes. It could design any change to be time-limited and only to be applicable to those needing to self-isolate with Covid. It might also think that post-pandemic there is likely to be a wider conversation about how we treat health risks and support those who are ill and cannot work. Reviewing sick pay would be sensible in that context.

- Cowburn A, Matt Hancock pressing for ‘increase in statutory sick pay’, The Independent, 13 March 2021, www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/matt-hancock-covid-statutory-sick-pay-b1816741.html

- Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, SPI-B: Impact of financial and other targeted support on rates of self-isolation or quarantine, 16 September 2020, 9 October 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/925133/S0759_SPI-B__The_impact_of_financial_and_other_targeted_support_on_rates_of_self-isolation_or_quarantine_.pdf; Brewer M and Gustafsson M, Time out: Reforming Statutory Sick Pay to support the Covid-19 recovery phase, Resolution Foundation, December 2020, www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2020/12/Time-out.pdf

- Adherence to the test, trace and isolate system: results from a time series of 21 nationally representative surveys in the UK (the COVID-19 Rapid Survey of Adherence to Interventions and Responses [CORSAIR] study), www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.15.20191957v1.full.pdf

- Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, SPI-B: Impact of financial and other targeted support on rates of self-isolation or quarantine, 16 September 2020, 9 October 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/925133/S0759_SPI-B__The_impact_of_financial_and_other_targeted_support_on_rates_of_self-isolation_or_quarantine_.pdf

- Fancourt D, Bu F, Wan Mak H and Steptoe A, Covid-19 Social Study: Results Release 28, UCL, 13 January 2021, https://b6bdcb03-332c-4ff9-8b9d-28f9c957493a.filesusr.com/ugd/3d9db5_bf013154aed5484b970c0cf84ff109e9.pdf

- Public Accounts Committee, (oral evidence session): COVID-19: Test, track and trace (part 1), 18 January 2021, https://committees.parliament.uk/event/3324/formal-meeting-oral-evidence-session/

- Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, SPI-B: Impact of financial and other targeted support on rates of self-isolation or quarantine, 16 September 2020, 9 October 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/925133/S0759_SPI-B__The_impact_of_financial_and_other_targeted_support_on_rates_of_self-isolation_or_quarantine_.pdf

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/disaster-medicine-and-public-health-preparedness/article/selfquarantine-noncompliance-during-the-covid19-pandemic-in-south-korea/44485280CA49B6C2B7A15F289D4DEB8C# ; https://www.ft.com/content/22544fbf-a5dd-4b3c-99c7-1341cb2b0eb

- BBC News, Covid hand-outs: How other countries pay if you are sick, 23 January 2021, www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-55773591

- Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, SPI-B: Impact of financial and other targeted support on rates of self-isolation or quarantine, 16 September 2020, 9 October 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/925133/S0759_SPI-B__The_impact_of_financial_and_other_targeted_support_on_rates_of_self-isolation_or_quarantine_.pdf

- Reed S and Palmer B, To solitude: Learning from other countries on how to improve compliance with self-isolation, Nuffield Trust, 12 January 2021, www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/to-solitude-learning-from-other-countries-on-how-to-improve-compliance-with-self-isolation-1; Patel J, Fernandes G and Sridhar D, How can we improve self-isolation and quarantine for covid-19?, The BMJ, 10 March 2021, www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n625

- Brewer M and Gustafsson M, Time out: Reforming Statutory Sick Pay to support the Covid-19 recovery phase, Resolution Foundation, December 2020, www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2020/12/Time-out.pdf

- OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), Paid sick leave to protect income, health and jobs through the COVID-19 crisis, OECD, 2 July 2020, www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/paid-sick-leave-to-protect-income-health-and-jobs-through-the-covid-19-crisis-a9e1a154/

- Raval A, Inside the ‘Covid Triangle’: a catastrophe years in the making, Financial Times, 5 March 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/0e63541a-8b6d-4bec-8b59-b391bf44a492

- Apply for a Test and Trace Support Payment, GOV.UK, www.gov.uk/test-and-trace-support-payment

- Butcher B and Cowling P, Covid: How many people get self-isolation payments?, BBC News, 1 March 2021, www.bbc.co.uk/news/56201754

- Brewer M and Gustafsson M, Time out: Reforming Statutory Sick Pay to support the Covid-19 recovery phase, Resolution Foundation, December 2020, www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2020/12/Time-out.pdf

- OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), Paid sick leave to protect income, health and jobs through the COVID-19 crisis, OECD, 2 July 2020, www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/paid-sick-leave-to-protect-income-health-and-jobs-through-the-covid-19-crisis-a9e1a154/

- Supporting document

- jobs-benefits-covid-challenge.pdf (PDF, 674.74 KB)

- Topic

- Coronavirus

- Keywords

- Health

- Position

- Health secretary

- Publisher

- Institute for Government