Local enterprise partnerships

Local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) are non-statutory bodies responsible for local economic development in England.

What are local enterprise partnerships?

Local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) are non-statutory bodies responsible for local economic development in England. They are business-led partnerships that bring together the private sector, local authorities and academic and voluntary institutions.

When were LEPs created?

LEPs were first introduced by the coalition government. The June 2010 budget announced the government’s intention to abolish the nine regional development agencies (RDAs), which had previously been responsible for local economic development, and replace them with new bodies responsible for local growth. A white paper in October 2010 then outlined how the RDAs would be wound down and replaced with LEPs.

Which areas of the UK are covered by a LEP?

LEPs do not exist in Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland, though the Scottish government has supported several regional economic partnerships that are similar partnerships between local government, the private sector, education and skills providers, and other local stakeholders.[1]

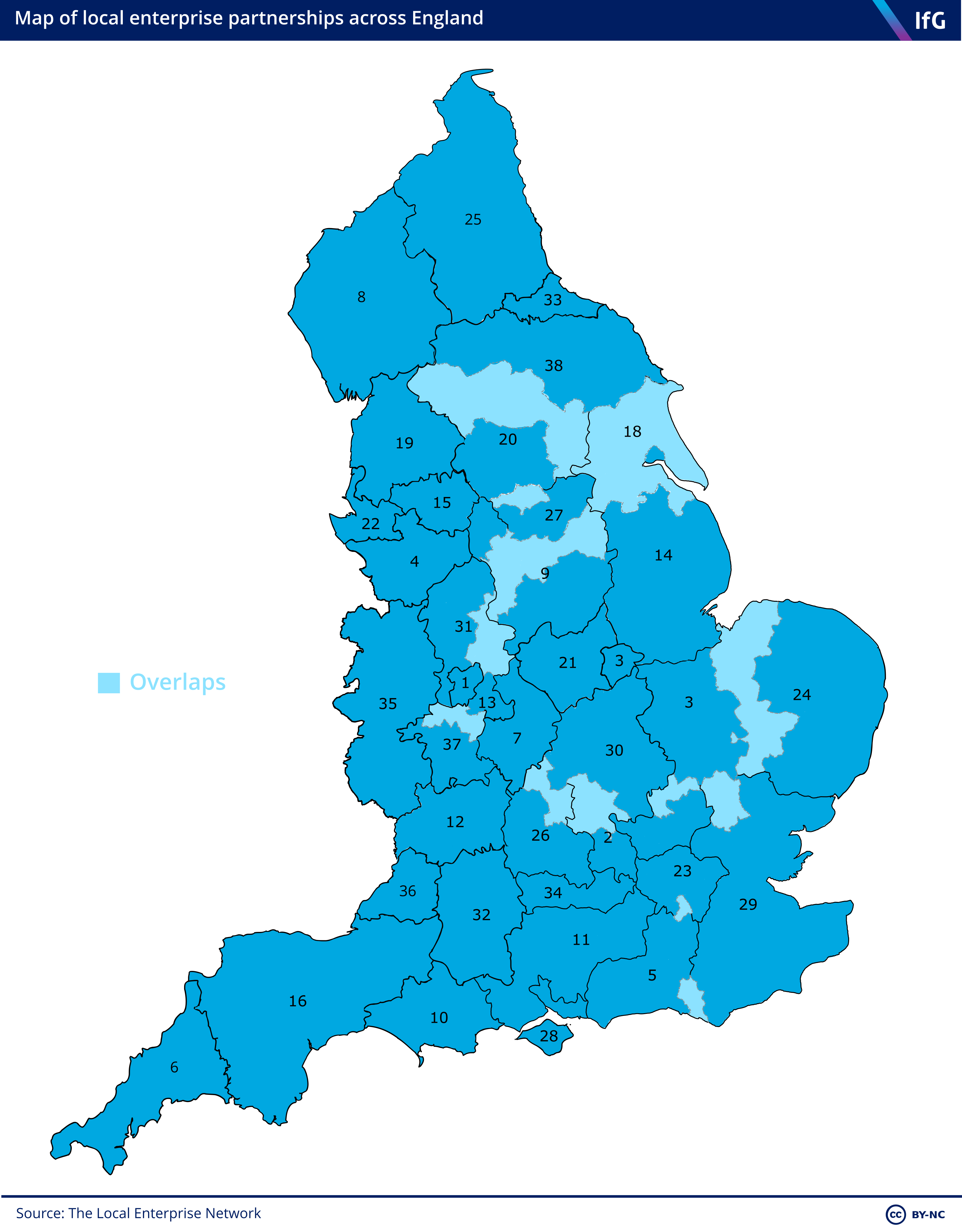

All areas of England are covered by a LEP, with 38 in total. LEPs are designed to reflect functional economic areas, taking into consideration things such as local labour markets – where people actually commute from and to. They also need to be large enough to offer sufficient economies of scale. As a result, LEPs cover multiple local authorities, and some local authorities lie within multiple LEPs.

What do LEPs do?

Some of LEPs’ functions include:

- working with central government to set local investment priorities

- working with local employers and job centres to help people back to work

- leading changes in how businesses are regulated locally

- supporting high-growth local businesses

- helping deliver national priorities such as digital infrastructure and renewable energy projects.

LEPs took over some (but not all) of the responsibilities of RDAs for local economic development. RDAs had also been responsible for promoting innovation and securing inward investment into their regions, responsibilities that reverted to central government after 2010.

The 2011 budget and accompanying Plan for Growth policy paper gave LEPs responsibility for managing ‘enterprise zones’. These are areas designated by central government where businesses receive incentives – such as business rates discounts – to set up or expand. The initial 24 enterprise zones were later increased to 44.

Under Theresa May’s government, LEPs were involved in the formulation and delivery of local industrial strategies. Since the Johnson government scrapped May’s 2017 Industrial Strategy in favour of Build Back Better: Our Plan for Growth in March 2020, it is unclear what the future is for these local industrial strategies.[2]

How do LEPs fit within the wider devolution landscape in England?

There are nine city regions in England that are covered by both a LEP and a mayoral combined authority (MCA). In some cases, such as Greater Manchester, these are coterminous; in others, such as North Tyne MCA and the North East LEP, their boundaries are not the same.

MCAs have more powers and responsibilities than LEPs, but both share responsibility for local economic development. In a 2018 paper on LEPs, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) emphasised the need for the two to work closely together in light of these overlapping responsibilities.[3]

How are LEPs run?

LEPs take varying corporate structures, with the most common being company limited by guarantee and unincorporated voluntary partnerships. All LEPs must have a private sector chair, and the majority of their board members should be from the private sector. A report from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in 2020 found that the number of full-time staff in LEPs ranged from 0 (that is, all staff are seconded from other organisations) to 520, with the median number being 16.[4]

All LEPs participate in the LEP Network, which provides a forum for co-ordination on issues of shared importance and allows LEPs to share best practice.

How are LEPs funded and what resources do they help manage?

LEPs were initially intended fund their own day-to-day funding, with the October 2010 white paper on local growth encouraging LEPs to consider how to leverage private investment to do so.[5] LEPs were allocated one-off start-up funding in August 2011. However, since then LEPs have had access to central pots of money to support their work locally, such as the Regional Growth Fund and the Growing Places Fund.

Many LEPs also received money through local growth deals, which were awarded by central government based on each LEP’s multi-year strategic economic plan. Some LEPs were involved in supporting bids for city deals – bespoke packages of funding and powers to support growth in city areas.

In all, LEPs received almost £12bn in public funding between their creation in 2010/11 and 2019/20. In 2019, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) expressed concern that this spending was not being properly evaluated by MHCLG, the department responsible for LEPs.[6] The PAC inquiry also found that LEPs had underspent their Local Growth Fund allocations by over £1.1bn in the three years to the end of 2017/18, raising concerns that they lack the capacity to deliver ambitious projects for local growth.[7]

What was the role of LEPs in the delivery of European Structural Funds?

LEPs have also been responsible for advising central government on the management of funding from the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund and part of the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development. These funds were allocated by the EU to specific areas, and between 2014 and 2020 LEPs were responsible for developing strategies for spending their allocations from these funds, and monitoring the delivery of their objectives. These strategies had to be signed off by central government.[8]

What is the role of LEPs in the ‘levelling up’ agenda?

It is not yet clear what role LEPs might play in the delivery of the government’s levelling up policies. Some LEPs led on bidding for freeports – low tariff zones with additional tax incentives for businesses – one of the Conservative manifesto policies linked to levelling up.[9] However, policies such as the Towns Fund and the Levelling Up Fund do not funnel money through LEPs, instead relying on local authorities to deliver the programmes and investments linked to these schemes.

Despite the role that LEPs played in the delivery of European Structural Funds, the government has not confirmed whether they will also be a part of the Shared Prosperity Fund (SPF), which will replace those European funds. LEPs are not one of the managing authorities for the Community Renewal Fund, a pilot for the SPF, suggesting that LEPs may not be involved in administering funds from the SPF when it is launched in 2022.

- Scottish Government, ‘Regional Economies and Economic Partnerships’, Economic Action Plan 2019-20, retrieved 6 July 2021, www.economicactionplan.mygov.scot/place/regional-economies

- Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee, Oral evidence: Post-pandemic economic growth: Levelling up – local and regional structures and the delivery of economic growth, HC 115, 18 May 2021, www.committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/2219/pdf

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Strengthening Local Enterprise Partnerships, July 2018, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/728058/Strengthened_Local_Enterprise_Partnerships.pdf

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Local Enterprise Partnerships Capacity and Capabilities Assessment, BEIS Research Paper Number: 2020/011, July 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/912341/lep-assessment-2019.pdf, p. 19.

- HM Government, Local growth: Realising every place’s potential, Cm 7961, The Stationary Office, 28 October 2010, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32076/cm7961-local-growth-white-paper.pdf, p. 15.

- Public Accounts Committee, Local Enterprise Partnerships: progress review, 5 July 2019, retrieved 14 June 2021, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubacc/1754/175406.htm#_idTextAnchor005

- Public Accounts Committee, Local Enterprise Partnerships: progress review, 5 July 2019, retrieved 14 June 2021, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubacc/1754/175407.htm#_idTextAnchor010

- HM Government, Structural and Investment Fund Strategies: Preliminary guidance to Local Enterprise Partnerships, April 2013, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/190879/13-747-structural-and-investment-fund-strategies-preliminary-guidance-to-leps.pdf

- ‘LEP led Freeport bid gets green light from Chancellor’, LEP Network, 3 March 2021, retrieved 14 June 2021, www.lepnetwork.net/news-and-events/2021/march-2021/lep-led-freeport-bid-gets-green-light-from-chancellor

- Topic

- Public finances Devolution

- Keywords

- Business Economy Regional economic growth

- United Kingdom

- England

- Publisher

- Institute for Government