Performance Tracker 2023: Children's social care

The sector faces workforce shortages alongside increasing demands; with referrals at pre-pandemic levels and an increasingly complex caseload.

Local authorities are struggling with serious workforce shortages as the sector faces the highest level of turnover since 2013 and the first decline in overall numbers of children’s social workers in a decade, even as the need for social workers rises. Difficulties in recruitment and retention have exacerbated the sector’s existing over-reliance on agency staff, fuelling higher costs. Alongside these cost pressures, a shortage of residential placements is driving higher prices, adding to the financial squeeze on other children’s services and wider local authority budgets, as outlined in the ‘Neighbourhood services’ chapter. This squeeze is part of a long-term trend that has seen spending on acute services such as family support rising by 43.2% between 2009/10 and 2021/22 at the expense of universal and preventative services such as Sure Start children’s centres and other spend on children under five, which fell by 73.4% over the same period.

Meanwhile, demands on the sector are increasing. Referrals to children’s services have returned to pre-pandemic levels while the number of children in care continues to rise. There is also evidence that cases have become more complex, with additional pressures from a record level of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Though the government has recently outlined a future vision for the sector,* it has been criticised for lacking the funding or policy changes needed to tackle the scale of problems and as such it may struggle to improve the quality of social care provision.

This chapter examines the current state of children’s social care in England. These services are provided by upper tier local authorities, which are legally obliged to provide support for disabled children, to protect children from harm, and to take responsibility for ‘children in care’,** including through foster and residential care placements.

Spending on children’s social care is increasing pressure on local authority budgets

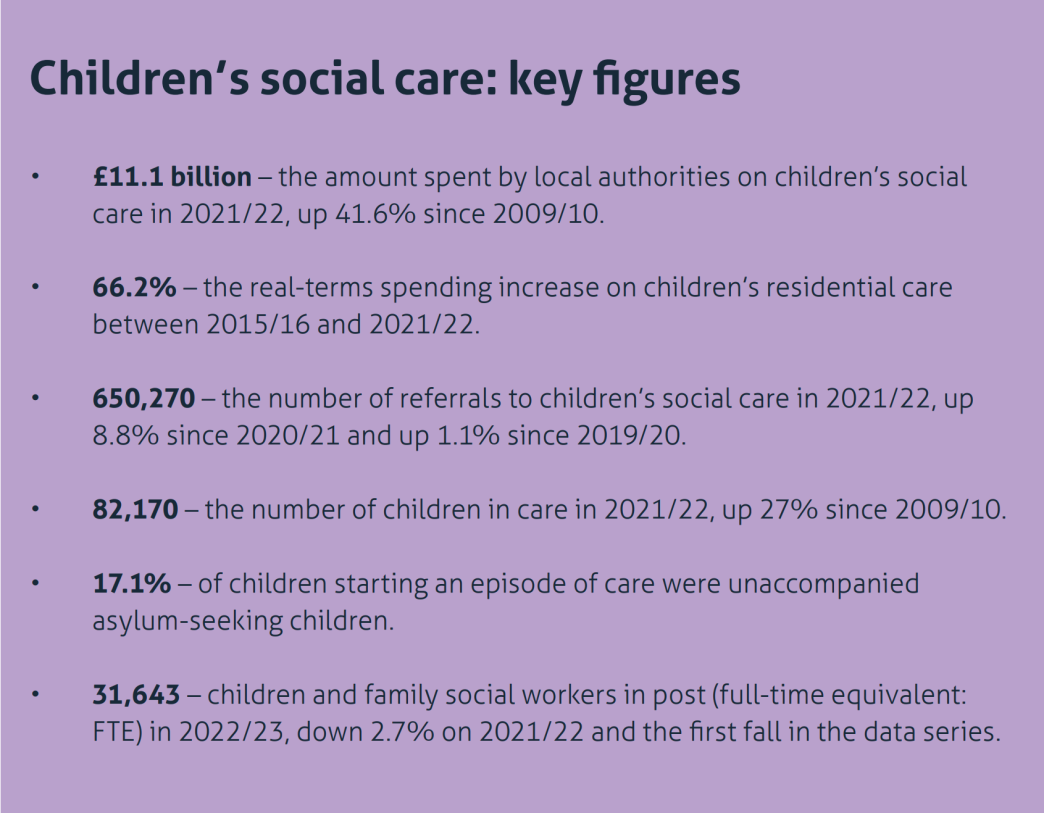

Local authorities spent £11.1bn on children’s social care in 2021/22, up £0.5bn in a year – of this, £0.48bn was attributable to pandemic-related expenditure, such as higher residential care and agency staff costs.*** Between 2009/10 and 2021/22, spending increased by 41.6% in real terms. By comparison, the number of children in England grew by less than 10% over the same period.

This sustained increase in children’s social care spend continues to squeeze the budget available for other children’s services and other areas of local authority spending. Nationally, councils ended up spending more than they budgeted on children’s social care each year from 2014/15 to 2019/20. 150 Local Government Association, ‘LGA: Eight in 10 councils forced to overspend on children’s social care budgets amid soaring demand’, 3 June 2021, retrieved 21 September 2023, www.local.gov.uk/about/news/lga-eight-10-councils-forced-overspend-childrens-social-care-budgets-amid-soaring-demand Local authorities have continued to overspend, and in 2021/22, 46% of councils overspent their budgets by at least 20%, while 10% of councils overspent their budgets by at least 40%. 151 Institute for Government analysis of Department for Education, ‘Local authority revenue expenditure and financing England: 2021 to 2022 individual local authority data – outturn’ (Revenue outturn social care public health services (RO3) 2021 to 2022), 23 March 2023, retrieved 8 September 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/local-authority-revenue-expenditure-and-financing-england-2021-to-2022-individual-local-authority-data-outturn; Department for Education, ‘Local authority revenue expenditure and financing England: 2021 to 2022 budget individual local authority data’ (Revenue account (RA) budget 2021 to 2022), 24 June 2021, retrieved 22 September 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/local-authority-revenue-expenditure-and-financing-england-2021-to-2022-budget-individual-local-authority-data In Bolton, overspend on children’s services amounted to almost 10% of the local authority’s entire net revenue budget for 2022/23. 152 Gilmore A, ‘Bradford councillor fears £3.8m children’s services overspend could lead to s114’, Room151, 20 July 2023, retrieved 21 September 2023, www.room151.co.uk/funding/bradford-councillor-fears-33-8m-childrens-services-overspend-could-lead-to-s114

*Department for Education, Stable Homes, Built on Love: implementation Strategy and Consultation: Children’s Social Care Reform 2023, February 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1147317/Children_s_social_care_stable_homes_consultat…

**A child who has been in the care of their local authority for more than 24 hours is known as a looked-after child. Looked-after children are also often referred to as children in care.

***For more details on the breakdown of this spending see Davies N and Fright M, Performance Tracker 2022/23: Spring update, ‘Children’s social care’, Institute for Government, 23 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/performance-tracker-2022-23/childrens-social-care

Decision makers have prioritised spending on more acute children’s social care at the expense of other services for children. Between 2009/10 and 2021/22, spending on safeguarding children and young people increased by 27.1%,* and on children in care by 49.4%. Over the same period, spending on other services for young people (which includes youth work, activities for young people and teenage pregnancy services) was cut by 60.8%, while spending on Sure Start children’s centres and other spend on children under five fell by 73.4%.

*Figures have been deflated using a ‘smoothed-deflator’ for all financial figures. For more details on this see Methodology.

The government’s independent review of children’s social care argued that prioritising acute responses at the expense of earlier support can lead to cases escalating. 173 MacAlister J, The independent review of children’s social care – final report, May 2022, pp. 25, 49, 55, www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-childrens-social-care-final-report Consequently, the review proposed a roughly £2.6bn uplift to children’s social care spending between 2023 and 2027 and a rebalancing of priorities away from crisis interventions towards earlier stage interventions with an annual amount of £1bn ring-fenced for family help. However, the government has not implemented this recommendation.

Higher residential care costs are driving up spending pressures in social care

Between 2015/16 and 2021/22, the amount spent on children’s residential care increased by 66.2% in real terms. This includes a 14.6% increase in 2021/22 alone, the largest real-terms increase since this data started being collected in 2015/16. 174 Department for Education, ‘LA and school expenditure: Financial year 2021–22’, 8 December 2023, retrieved 22 September 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/la-and-school-expenditure/2021-22#dataBlock-9593c67c-1035-423c-dfc1-08dacc6b24db-…; This is a major factor driving overall spending increases because spending on residential care comprised approximately a third of spending on children in care and a seventh of all children’s social care spend in 2021/22.

Higher costs have been driven by both supply constraints and demand pressures. On the supply side, children’s homes and other forms of residential care have few places available, with 29% of providers in February 2023 reporting over 95% occupancy, up from only 15% of providers in June 2019. 175 Revolution Consulting, ‘CHA “State of the Sector” survey 9 Spring 2023’, April 2023, retrieved 21 September 2023, p. 16, www.revolution-consulting.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/CHA-Spring-2023-final.pdf

Some areas face particularly significant shortfalls in local provision. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) found that North West England has 23% of all places in children’s homes, yet 17% of children in care, while London has just 6% of total places in children’s homes but 11% of the country’s children in care. 176 Competition and Markets Authority, Children’s social care market study final report, 22 March 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-social-care-market-study-final-report/final-report#outcomes-from-the-placements-market Lack of adequate local accommodation has negative consequences for children; for instance, leading to them being moved far from family and wider kinship networks.* More than 33% of children in care living in children’s homes, secure homes or semi-independent homes are placed more than 20 miles from their home. 177 Samuel M, ‘More children in care placed far from home, increasing risk of poorer wellbeing, finds research’, Community Care, 25 April 2023, retrieved 21 September 2023, www.communitycare.co.uk/2023/04/25/more-children-in-care-placed-far-from-home-increasing-risk-of-lower-wellbeing-finds-research As at March 2018, in England more than 2,000 children in care were more than 100 miles from home. 178 Competition and Markets Authority, Children’s social care market study final report, 22 March 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-social-care-market-study-final-report/final-report#outcomes-from-the-placements-market

Accommodation for children with complex and specialist needs is the scarcest; for example, there are no secure children’s homes** in London or the West Midlands. 179 Ofsted, ‘Main findings: children’s social care in England 2023’, 8 September 2023, retrieved 22 September 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/childrens-social-care-data-in-england-2023/main-findings-childrens-social-care-in-england-2023#childrens-homes-of-al…; Ofsted analysis showed that, as of March 2020, only 5% of children’s homes said that they could accommodate complex health needs. 180 Ofsted, ‘What type of needs do children’s care homes offer care for?’, 8 July 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/what-types-of-needs-do-childrens-homes-offer-care-for/what-types-of-needs-do-childrens-homes-offer-care-for

The complex needs sector has come under additional scrutiny following the harrowing treatment of children under the care of the Hesley Group. 181 Butler P, ‘Urgent calls for reform after horrific abuse of young people at private care homes’, The Guardian, 20 April 2023, retrieved 21 September 2023, www.theguardian.com/society/2023/apr/20/urgent-calls-for-reform-after-horrific-abuse-of-young-people-at-private-care-homes The government is implementing changes to the sector and oversight regime for complex needs; 182 Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel, ‘Experts demand major overhaul of safeguarding system to protect children with disabilities from abuse at children’s homes’, press release, 20 April 2023, retrieved 22 September 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/experts-demand-major-overhaul-of-safeguarding-system-to-protect-children-with-disabilities-from-abuse-at-childrens-homes&n…; this has led some providers to withdraw from the market, reducing the supply of accommodation still further. 183 Institute for Government interview.

Problems with supply have been compounded by higher demand. Higher than usual numbers of foster parents are withdrawing,*** which has led to a shortfall in foster carers, 184 Koutsounia A, ‘One in eight fostering households quit last year, finds Ofsted’, Community Care, 25 November 2022, retrieved 22 September 2023, www.communitycare.co.uk/2022/11/25/one-in-eight-fostering-households-quit-2022-ofsted meaning local authorities have to make greater use of residential care. Second, following criticism from campaigners and the children’s commissioner, 185 Children’s Commissioner, ‘Ban the use of unregulated accommodation for the under 18s in care’, press release, 10 September 2020, retrieved 22 September 2023, www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/news/ban-the-use-of-unregulated-accommodation-for-under-18s-in-care the government withdrew the use of unregulated accommodation for under 16-year-olds from September 2021. 186 Foster D, Looked after children: out of area, unregulated and unregistered accommodation (England), House of Commons Library, 12 November 2021, retrieved 17 September 2023, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7560/CBP-7560.pdf While intended to improve the quality of children’s homes through better oversight, 187 Department for Education, ‘Government bans unregulated accommodation for young people in care’, press release, 23 March 2023, accessed 18 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/government-bans-unregulated-accommodation-for-young-people-in-care the practice may be continuing in some areas, and may have placed extra demands on the system. This pressure will intensify given the decision to extend this to 16- and 17-year-olds from October 2023. 188 Department for Education, ‘Government bans unregulated accommodation for young people in care’, press release, 23 March 2023, accessed 18 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/government-bans-unregulated-accommodation-for-young-people-in-care Research commissioned by the County Councils Network (CCN) suggests that the Department for Education (DfE) has allocated £123m to cover the impact of these changes over the next three years, but when taking account of demand growth, the CCN estimates the total cost to local authorities could be nearly three times this. 189 ‘Demand and Capacity of Homes for Children in Care’, Newton Europe, 20 July 2023, retrieved 18 August 2023, p. 18, www.countycouncilsnetwork.org.uk/download/4984/?tmstv=1692354671

Costs have also been driven up by the profit levels of private residential care providers, which account for 83% of residential care places. A recent report by the CMA found that private providers were making higher profits through higher prices and provision that did not always meet the needs of children, such as a lack of local placements and difficulties accessing appropriate care, therapies or facilities. 190 Competition and Markets Authority, Children’s social care market study final report, 22 March 2022, pp. 29–30, www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-social-care-market-study-final-report/final-report Some industry surveys, though, have suggested higher inflation, costs of living and staffing recruitment and turnover problems might have decreased operating profits over the past year. 191 Revolution Consulting, ‘CHA “State of the Sector” survey 9 Spring 2023’, April 2023, retrieved 21 September 2023, www.revolution-consulting.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/CHA-Spring-2023-final.pdf

The DfE has now labelled the risk of market failure for children in care placement as “critical to very likely” over the 2023/24 financial year due to rising prices and its assessment that local authorities are increasingly unable to afford appropriate placements to meet the needs of children in their care. 192 Department for Education, ‘Consolidated annual report and accounts: For the financial year ended 31 March 2023’, 18 July 2023, retrieved 18 August 2023, p. 118, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1171616/Department_for_Education_Consolidated_annual_…;

*Children in kinship care live either full-time or the majority of the time with family friends or relatives who are not their parents.

**Secure children’s homes house children between the ages of 10 and 17 and restrict their liberty to ensure their safety. This can occur if they have been remanded or sentenced to custody or placed there on welfare grounds. For further details see https://frg.org.uk/get-help-and-advice/a-z-of-terms/secure-childrens-home

***It remains unclear why more foster carers are exiting the sector. Analysis from ADCS suggests that this may be linked to carers re-evaluating priorities since the pandemic and broader cost of living pressures. See https://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ADCS_Safeguarding_Pressures_Phase_8_Full_Report_FINAL.pdf, p. 92.

There are increasing demands on the social care sector

Referrals have returned to pre-pandemic levels

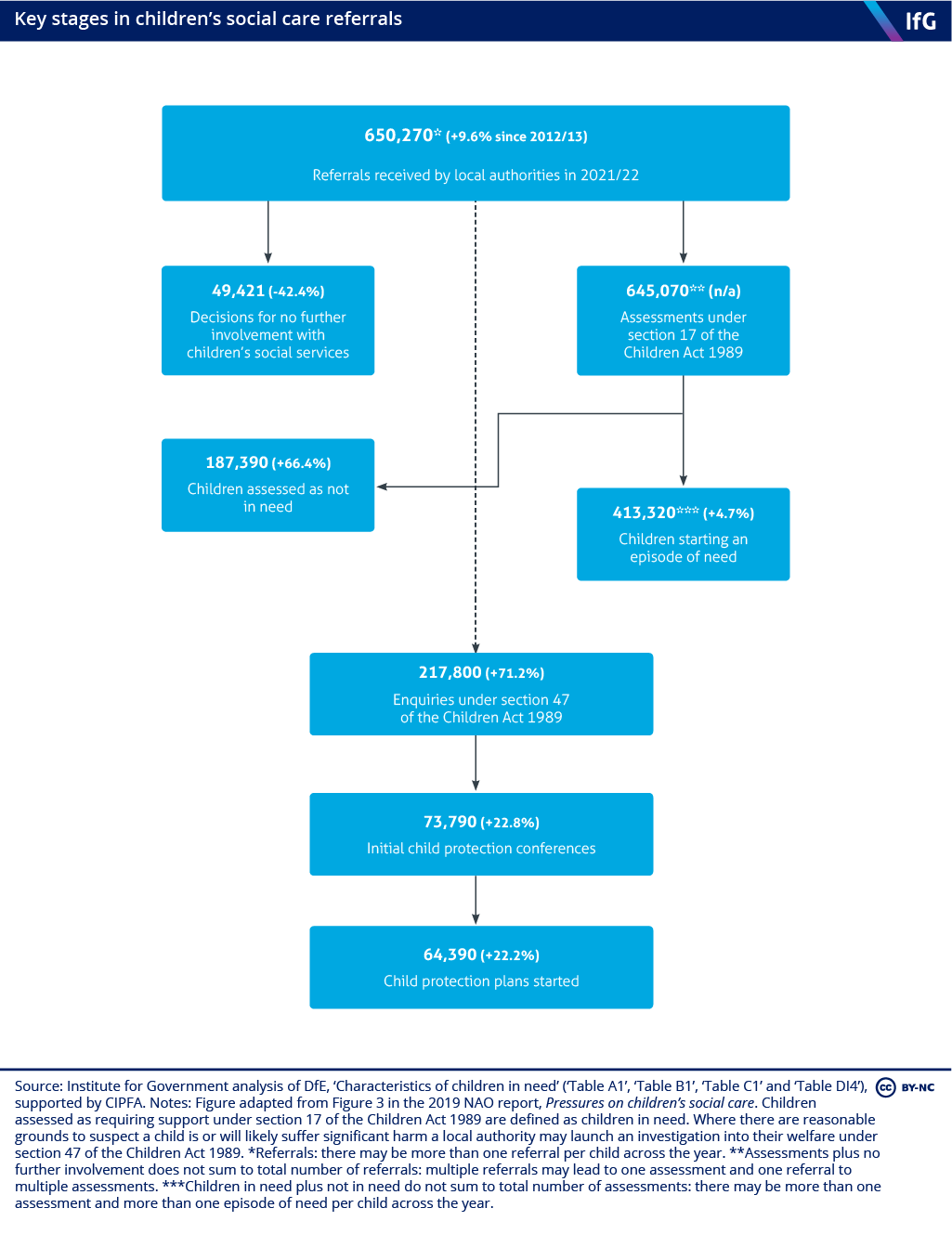

Referrals to children’s social care fell sharply during the pandemic but have now returned to pre-pandemic levels, rising by approximately 52,500 in 2021/22 (8.8%).

Part of the reason for the increase in referral numbers is that, as lockdown restrictions were reduced, potentially vulnerable children have had greater contact with public services. Schools are the second highest source of referrals to social care; they referred 59% more cases in 2021/22 than in 2020/21, reversing the large fall (30.6%) in referrals seen between 2019/20 and 2020/21.

Referrals are now slightly (1.1%) higher than in 2019/20, but this is not sufficient to make up for all the missing referrals during the pandemic. It is unclear whether these will show up at some later date. Some local authorities responding to a survey by the DfE reported that, continuing the pre-pandemic trend, the nature of cases coming forward appears to be more complex,* which may add pressures to the system. Analysis from the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory finds that there is a cohort of children with complex needs that are seen as too ‘challenging’ for secure children’s homes, including children with very complex mental health needs.

196

Roe A, What do we know about children and young people deprived of their liberty in England and Wales? An evidence review, Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, 9 February 2022, retrieved 22 September 2023,

www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/children-and-young-people-deprived-of-their-liberty-england-and-wales

There are also some reasons to think that financial pressures resulting from the 2023 cost of living crisis could add to pressure on children’s social care. We heard from one interviewee that financial pressures can lead families to cut back on social activities and basic needs like beds and bedding, contributing to mental health issues for children. 197 Institute for Government interview. And a 2022 British Association of Social Workers survey of members raised concerns that cost-of-living pressures on families could lead to unmanageable caseloads. 198 Simpson F, ‘Children’s social work caseloads predicted to soar as living costs rise’, Children and Young People Now, 7 September 2022, retrieved 7 July 2023, www.cypnow.co.uk/news/article/children-s-social-work-caseloads-predicted-to-soar-as-living-costs-rise

*Ofsted reports that local authorities use the term ‘complex needs’ to cover four broad categories of need including mental health needs, behavioural needs that lead to safeguarding concerns, behavioural needs linked to learning difficulties and physical health needs. For further details see https://socialcareinspection.blog.gov.uk/2023/05/23/children-with-complex-needs-in-childrens-homes

The number of children on child protection plans remains relatively steady, while the number of children in care has continued to grow

The number of child protection plans (CPPs)* rose in 2021/22 for the first time in four years and now stands at around 51,000.

204

Department for Education, ‘Characteristics of children in need’, 27 October 2022, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/characteristics-of-children-in-need/2022

It is too early to say whether this recent increase is the start of a sustained trend. Ofsted has stated that the increase “is partially due to social workers’ cautiousness when considering risks in the context of a new, post-lockdown environment”.

205

Ofsted, ‘Children’s social care 2022: recovering from the COIVD-19 pandemic’, 27 July 2022, retrieved 22 September 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-social-care-2022-recovering-from-the-covid-19-pandemic/childrens-social-care-2022-recovering-from-the-co…;

Social workers are now supporting a slightly higher number of children in care.** As of March 2022, there were approximately 82,000 children in care, which was up 1.5% on the previous year and 2.7% higher than in March 2020. 206 Department for Education, ‘Children looked after in England including adoptions 2022’, 12 November 2022, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoptions/2022 This continues a longer-term rise seen over the past decade. 207 Department for Education, ‘Children looked after in England including adoptions 2022’, 12 November 2022, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoptions/2022 Growth rates are highest for older children, largely due to increases in the number of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and the length of time children spend in care.***, 208 Department for Education, Drivers of activity in children’s social care: research report, May 2022, accessed 22 September 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1080111/Drivers_of_Activity_in_Children_s_Social_Care…; As a result, older children make up a growing proportion of those in care.

*After a referral, a child may be assessed under section 47 of the Children Act 1989 to be judged at a reasonable risk of harm. If that happens, a CPP is agreed, which commits a local authority to support the child; this plan may cover their care while the child lives with their family or, for example, while they are in residential care.

**A child who has been in the care of a local authority for more than 24 hours. Generally, these children are accommodated in children’s homes, residential settings (such as secure units) or with foster parents.

***The key driver of this trend remains unclear. Multiple explanations have been outlined in DfE, ‘Drivers of activity in children’s social care’ research report, May 2022, accessed September 2022, pp. 7–8, 18–24, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1080111/Drivers_of_Activity_in_Children_s_Social_Care…;

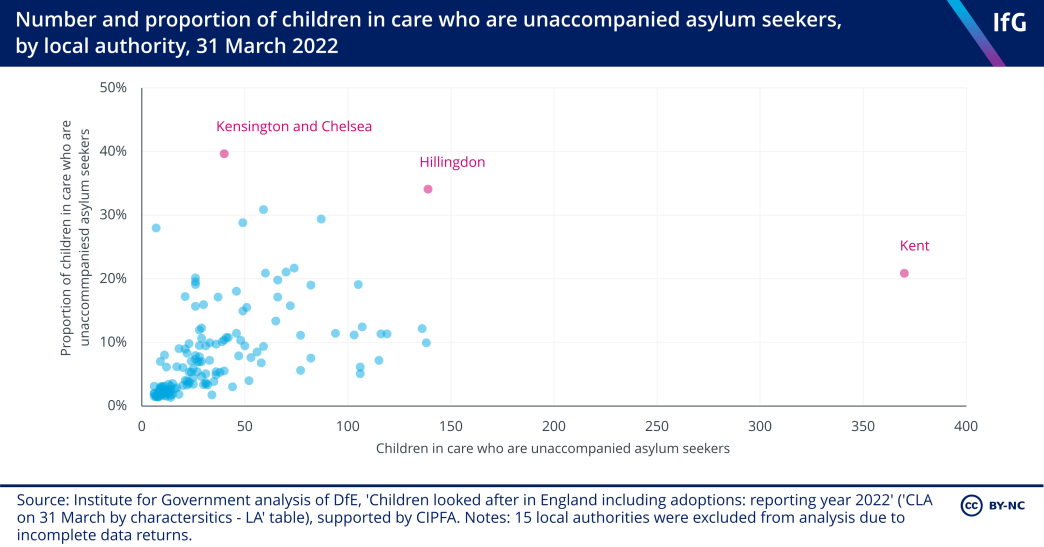

There is record demand from current and former unaccompanied asylum-seeking children

The number of children in care who entered the UK as unaccompanied asylum seekers increased by 34.2% to 5,570 in 2021/22 and is now 8.2% higher than the previous peak of 5,150 in 2018/19. Unaccompanied asylum-seeking (UAS) children now account for 17.1% of all children starting an episode of care, the highest on record. 211 Institute for Government analysis of Department for Education FOI data (SSDA903) and Department for Education, ‘Children looked after in England including adoptions’, reporting year 2022, supported by CIPFA, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/characteristics-of-children-in-need These children have frequently suffered complex traumas, often linked to the reason for leaving their home countries, travel and occasionally experience of human trafficking; as a result, these children often need additional levels of support from local authorities. 212 Institute for Government interview.

Councils are also managing demand from a large number of former UAS children who have subsequently been granted asylum. Between 2010 and 2022, 19,955 UAS children were granted asylum, 219 Home Office, ‘Immigration system statistics data tables, year ending December 2022’, 23 February 2023, retrieved 8 September 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/immigration-system-statistics-data-tables-year-ending-december-2022 with local authorities supporting 11,650 former UAS children care leavers aged 17–21 as of 31 March 2022. 220 Local Government Association, ‘Debate on accommodation of asylum-seeking children in hotels, House of Commons, 7 June 2023’, 5 June 2023, retrieved 8 September 2023, www.local.gov.uk/parliament/briefings-and-responses/debate-accommodation-asylum-seeking-children-hotels-house Former UAS children now account for 26% of care leavers aged 19–21.

These pressures are not distributed evenly across the country, with some councils facing notably higher pressures. 221 Institute for Government interview. , 222 Hill J, ‘Kent’s legal threat to Patel over child asylum seeker “burden”’, Local Government Chronicle, 7 June 2021, retrieved 22 September 2023, www.lgcplus.com/services/children/kents-legal-threat-against-patel-over-child-asylum-seeker-burden-07-06-2021 Indeed, for local authorities reporting data as at 31 March 2022, 9% of local authorities’ UAS children make up more than 20% of their children in care; with two fifths of children in care in Kensington and Chelsea coming from a UAS children background. 223 Institute for Government analysis of Department for Education, ‘Children looked after in England including adoptions: reporting year 2022’, ‘CLA on 31 March by characteristics – LA’ table, 13 July 2022, retrieved 21 September 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoptions/2022#content Notably, Kent County Council has the highest number of UAS children (370), which is more than three times the total number of UAS children in care in the North East (111) and similar to the volume in the South West (387) and Yorkshire and the Humber (349).*, 224 Institute for Government analysis of Department for Education, ‘Children looked after in England including adoptions: reporting year 2022’, ‘CLA on 31 March by characteristics – LA’ table, 13 July 2022, retrieved 21 September 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoptions/2022#content

*Data on UAS children has been withheld in some local authorities due to confidentiality, which may have contributed to relatively low figures for these regions.

The number of social workers fell in the past year and local authorities have been struggling to fill vacancies

The number of children’s and family social workers fell for the first time in a decade, down 2.7% in 2022/23. 228 Department for Education, ‘Children’s social work workforce 2022’, 23 February 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-s-social-work-workforce/2022

This has been due to both increases in staff leaving the workforce and a decline in social workers joining the profession. The number of leavers increased to 5,400 (or 17.1% of the total workforce) in 2022/23 – some 8.5% higher than 2021/22 and the highest number of leavers since comparable data started to be collected in 2013/14. 229 Department for Education, ‘Children’s social work workforce 2022’, 23 February 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-s-social-work-workforce/2022 The number of joiners fell to 4,800 in 2022/23 – down 12.5% compared to 2021/22 and the lowest number of joiners since comparable data started to be collected. 230 Ibid. This does not reflect a scaling back of jobs for social workers, but rather growing problems in filling the available vacancies.

There has been a marked increase in social worker vacancies, which now stand at 7,900 (or 20.0% of the available number of jobs), up 21.3% in 2022/23 and the highest on record. 233 Department for Education, ‘Children’s social work workforce 2022’, 23 February 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-s-social-work-workforce/2022 More than four fifths of local authorities (83%) when surveyed said that they are struggling to recruit children’s social care staff. 234 Local Government Association, Local Government Workforce Survey 2022, Research report, May 2022, 19 January 2023, retrieved 24 January 2023, www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/LG%20Workforce%20Survey%202022%20-%20Final%20for%20Publication%20-%20Tables%20Hard%20Coded.pdf

A high level of vacancies has made councils increasingly reliant on agency workers: 6,800 agency social workers were in post in 2022/23, up 13.4% on the previous year. As a result, in 2022/23, 17.6% of social workers were agency workers, up from 15.5% in 2021/22. 255 Department for Education, ‘Children’s social work workforce 2022’, 23 February 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-s-social-work-workforce/2022 And even then, these figures are an underestimate. Analysis from the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) shows a marked increase in the hiring of agency staff on a managed team rather than individual basis. 256 The Association of Directors of Children’s Services, Safeguarding pressures phase 8, December 2022, retrieved 24 January 2023, p. 103, https://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ADCS_Safeguarding_Pressures_Phase_8_Full_Report_FINAL.pdf Services contracted out in this manner are not recorded in agency data. 257 Institute for Government interview. When services are contracted out this way, local authorities face less flexibility and higher costs. 258 The Association of Directors of Children’s Services, Safeguarding pressures phase 8, December 2022, retrieved 24 January 2023, p. 103, https://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ADCS_Safeguarding_Pressures_Phase_8_Full_Report_FINAL.pdf

Combined, these factors have led to council spending on agency workers increasing by 38% over five years. 259 BBC News, ‘Children’s social work agency spending soars research suggests’, 28 December 2022, retrieved 24 January 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-64054446 The impact of problems recruiting and retaining care staff and foster carers was also cited as a problem for social care quality in the recent Competition and Markets Authority investigation. 260 Competition and Markets Authority, Children’s social care market study final report, 22 March 2022, www.gov.uk/cma-cases/childrens-social-care-study

This high level of churn among social worker also affects children, inhibiting the development of strong relationships with their social worker and adding disruption to their lives. 261 Children’s Commissioner, ‘Children’s Social Care – putting children’s voices at the heart of reform’, January 2022, retrieved 16 August 2023, p. 4, https://assets.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wpuploads/2022/01/cco_childrens_social_care_putting_childrens_voices_at_the_heart_of_reform.pdf

The most important factor in explaining difficulties retaining social workers is high caseloads. Issues related to being overworked were those most commonly cited by people considering leaving their jobs, 262 Department for Education, Longitudinal study of local authority child and family social workers (Wave 4), December 2022, retrieved 23 January 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1121609/Long_CAFSW_Wave_4_Report.pdf and the 2022 British Association of Social Workers annual survey found 52% of social workers were unable to cope with their workload. 263 The British Association of Social Workers, The BASW Annual Survey of Social Workers and Social Work: 2022, 20 March 2023, retrieved 8 September 2023, www.basw.co.uk/resources/basw-annual-survey-social-workers-and-social-work-2022 Staff had slightly higher volumes of cases in 2022 compared with either 2020 or 2021. Average caseloads are now somewhat lower than they were immediately pre-pandemic,* but the average caseload of each social worker remains higher than in 2015, with 16.6 cases per social worker in 2022 compared to 15 in 2015. 264 Department for Education, ‘Children’s social work workforce 2022’, 23 February 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-s-social-work-workforce/2022 Furthermore, as noted above, there is evidence that cases have become more complex on average since the pandemic. 265 Institute for Government interviews.

Cost-of-living pressures may become an increasingly important factor affecting whether or not people choose to join or stay in the sector. A full and final £1,925 pay offer to all local government employees, including social workers, has been rejected and three unions are balloting for industrial action. We have also heard that service providers are struggling to retain early help practitioner roles** due to competition from the retail sector, 266 Institute for Government interview. which can often offer higher wages. 267 Institute for Government interview. Up to 2019/20, social worker real-terms median social worker wages had fallen by 9.5% against 2009/10 levels and though this improved over the pandemic, real-terms median wages in 2021/22 were still 4.5% below 2009/10 figures. 268 Institute for Government analysis of Office for National Statistics, ‘Earnings and hours worked, occupation by four-digit SOC: ASHE Table 14’. Notes: Figures have been deflated using OBR CPI figures, www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/datasets/earningsandhoursworkedallemployeesashetable14

*The average caseload for 2019 was 16.9 cases per social worker, 17.4 cases per social worker in 2018 and 17.8 cases per social worker in 2017. For further details see https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-s-social-work-workforce/2022

**Early help practitioners support families to overcome issues and build their strengths.

The quality of children’s social care appears relatively stable

Regular inspections of children’s services were suspended during the pandemic, but these were resumed from 12 April 2021, which means we have a snapshot of service performance for some local authorities as they exited the pandemic. According to this, there has been an improvement in assessed compliance with inspected standards. Of the 74 inspection reports published by Ofsted between 2020/21 and 2022/23, over half were rated as outstanding or good (55.4%). Of the 40 full inspections that have been carried out since 31 March 2021, a total of 23 authorities were rated to be performing better than they had been pre-pandemic, while nine declined and four stayed at the same grade.*, 269 Ofsted, ‘Main findings: children’s social care in England 2022’, 7 July 2022, retrieved 24 January 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/childrens-social-care-data-in-england-2023/main-findings-childrens-social-care-in-england-2023 As of March 2023, some 90 authorities are rated good or outstanding (59.2%), 48 are requiring improvement (31.6%) and 14 are inadequate (9.2%), though many of these ratings are based on assessments that predate the pandemic. 270 Ofsted, ‘Main findings: children’s social care data for the Ofsted Annual Report 2021/22’, 13 December 2022, retrieved 24 January 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/childrens-social-care-data-for-the-ofsted-annual-report-202122

Another indicator of service quality is the number of serious incident notifications. Local authorities are required to send these to Ofsted when a child who was known to be at risk has died or come to harm. In 2022/23, there were 456 of these notifications, up 3% on 2021/22 and similar to the volume of cases seen in 2019/20. 271 Department for Education, ‘Serious incident notifications: Financial year 2022–23’, 25 May 2023, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/serious-incident-notifications It is too early to judge whether these figures will rise further in future years, given the increase in referrals.

There has been considerable public scrutiny of children’s social care following the tragic deaths of Arthur Labinjo-Hughes and Star Hobson, which led to a national inquiry into their deaths.

272

Letter from Annie Hudson, chair of the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel, to the secretary of state for education, 13 December 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/child-safeguarding-practice-review-panel-national-review-following-the-murder-of-arthur-labinjo-hughes

,

273

Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel, ‘New expert child protection units across the country’, press release, 26 May 2022,

www.gov.uk/government/news/new-expert-child-protection-units-across-the-country

In both cases social care service provision was affected by pandemic-era restrictions. While the findings of the national inquiry have informed the government’s plans to reform social care, other harrowing lockdown cases continue to progress through the courts, including the murder of Finley Boden, whose case appeared before the courts in May 2023.

274

Berg S, ‘Court papers show how killer parents won back their baby’, BBC News, 24 May 2023, retrieved 10 August 2023, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-65634100

*A further two authorities were assessed for the first time. Two more cannot be compared due to the merging of council boundaries.

The independent review of children’s social care, published in May 2022, called for a radical change in services to make them more responsive, respectful and effective. 284 MacAlister J, The independent review of children’s social care – final report, May 2022, p. 10, www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-childrens-social-care-final-report The review called for changes to working practices and processes, as well as reform of the children’s social care market. 285 MacAlister J, The independent review of children’s social care – final report, May 2022, p. 12, www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-childrens-social-care-final-report Echoing similar calls from the children’s commissioner, 286 Children’s Commissioner, ‘Children’s Social Care – putting children’s voices at the heat of reform’, January 2022, www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/cco_childrens_social_care_putting_childrens_voices_at_the_heart_of_reform.pdf it also called for children’s voices to be better heard when decisions are made on their care packages. 287 MacAlister J, The independent review of children’s social care – final report, May 2022, p. 12, www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-childrens-social-care-final-report Local authorities would need more funding to enact all these recommendations.

The government launched its response in February 2023, outlining ambitions for change in the sector and opening several consultations. 288 Department for Education, ‘Children’s social care: Stable Homes, Built on Love’, open consultation, 2 February 2023, www.gov.uk/government/consultations/childrens-social-care-stable-homes-built-on-love While the government’s response was broadly welcomed by the sector, 289 Local Government Association, ‘Children’s social care implementation strategy: LGA response’, 2 February 2023, www.local.gov.uk/about/news/childrens-social-care-implementation-strategy-lga-response the government has been criticised for the small scale and slow pace of change, 290 Samuel M, ‘Care review lead: government must go further and faster in response’, Community Care, 2 February 2023, www.communitycare.co.uk/2023/02/02/care-review-lead-government-must-go-further-and-faster-in-response and for providing only 20% of the funding called for by the independent review. 291 Samuel M, ‘DfE provides 20% of funding urged by care review in response’, Community Care, 2 February 2023, www.communitycare.co.uk/2023/02/02/dfe-provides-20-of-funding-urged-by-care-review-in-response The House of Lords Public Services Committee recently criticised the government’s strategy for a lack of engagement from relevant departments across Whitehall, its lack of funding and its limited discussion of the issues facing the residential care market. 292 House of Lords Public Services Committee, A response to the Children’s Social Care Implementation Strategy: 3rd Report of Session 2022–23 (HL Paper 201), 25 May 2023, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5803/ldselect/pubserv/201/201.pdf

- Topic

- Public services

- Position

- Health secretary

- Department

- Department of Health and Social Care

- Public figures

- Steve Barclay

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government