The Illegal Migration Bill: seven questions for the government to answer

Seven questions the government needs to answer about the Illegal Migration Bill if it has any chance of helping the PM ‘stop the boats'.

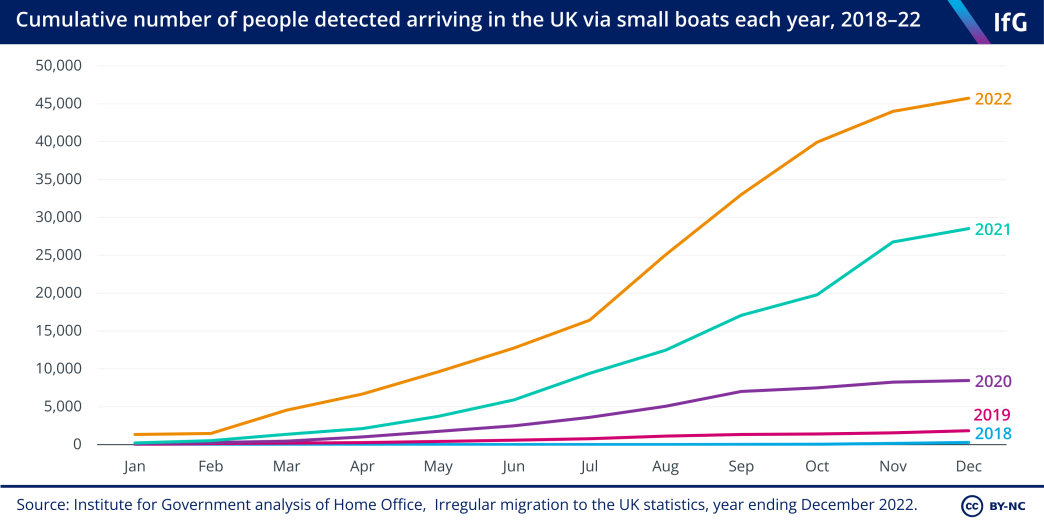

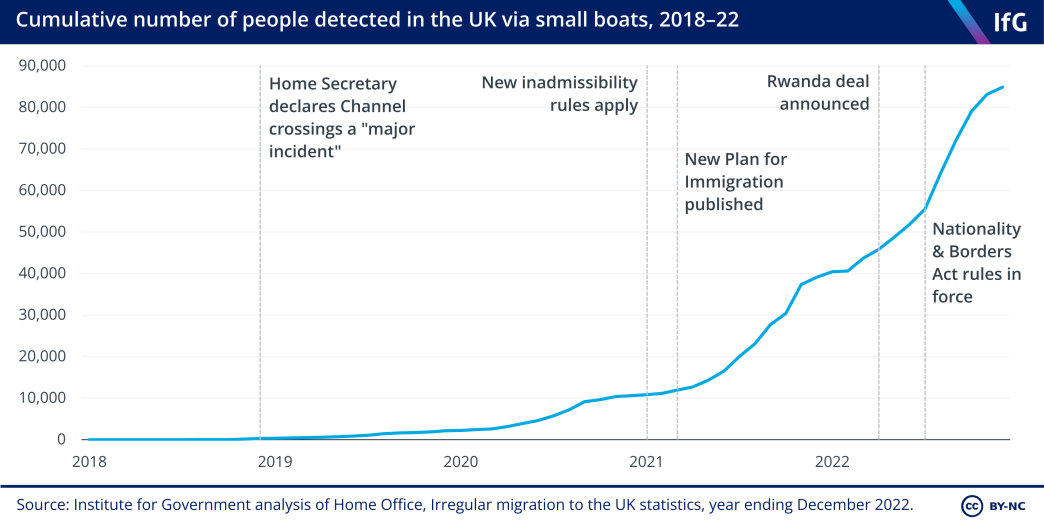

One of the five key pledges Rishi Sunak set out in January was to stop asylum seekers arriving in the UK by small boats crossing the English Channel. The number of people arriving this way has increased in recent years, from the low hundreds before 2020 to 45,755 people in 2022.

43

Home Office, ‘Irregular migration to the UK, year ending December 2022’, 23 February 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/irregular-migration-to-the-uk-year-ending-december-2022/irregular-migration-to-the-uk-year-ending-december-2022

Tragically, more than 130 people have died or gone missing trying to cross the Channel since 2019.

44

Missing Migrants Project, ‘Europe’, International Organization for Migration, [no date], retrieved 10 March 2023, https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/europe?region_incident=All&route=3896

Of those who arrived safely, the vast majority (around 90%) have claimed asylum

45

Home Office, ‘How many people do we grant protection to?’, 23 February 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-system-statistics-year-ending-december-2022/how-many-people-do-we-grant-protection-to

and the Refugee Council estimates that over two thirds of these claims are likely to be successful under the current system.

46

Refugee Council, The Truth About Channel Crossings, March 2023, www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/information/resources/the-truth-about-channel-crossings/

To act on the prime minister’s commitment the home secretary, Suella Braverman, has introduced the Illegal Migration Bill to parliament. The new bill aims to deter people from crossing the Channel in small boats by preventing those that do so from claiming asylum in the UK, detaining and removing them from the country.

The new legislation seeks to achieve this in several ways:

- It places a new duty on the home secretary to remove those entering the UK by irregular means via a safe country. In practice, this means almost everyone arriving by small boat from France, and over 85% of all irregular arrivals. The only exceptions to this duty are for people at risk of “serious and irreversible harm” 47 The legislation does not define “serious and irreversible harm”, instead including a placeholder which will allow the government to do so at a later date. There is a risk that any government definition conflicts with the interpretation of the same issue by the ECtHR. and unaccompanied children until they turn 18.

- All people who arrive irregularly – including those exempted from the duty to remove – are to be deemed permanently “inadmissible” to the UK’s asylum system and cannot challenge their removal using rules related to modern slavery. Three quarters of people detained for return after arriving by small boat in 2021 were referred as potential victims of modern slavery (and two thirds between January and September 2022), and the government is seeking to close this pathway. Almost everyone referred was subsequently released from detention, either by the Home Office or on bail by a judge.

- The government would be able to detain arrivals for 28 days without access to bail and unable to appeal. 48 Except for judicial review in very limited circumstances and applications against unlawful detention on the limited grounds of habeas corpus. After that, the government will be able to continue to detain someone for as long as the home secretary considers there to be a “reasonable prospect of removal” from the UK, though they may be granted bail by an immigration judge.

- The government will be able to return people to the country from which they arrived or to their home country if the government deems it “safe”. It would also be able to send them to a third country where the home secretary considers there to be no serious risk of persecution. This would include Rwanda as part of its asylum removals scheme.

- The bill also includes plans for a new cap on the number of people who can arrive in the UK via safe and legal routes, to be voted on in parliament each year. But this plan would only be enacted once the small boats issue has been resolved.

The government is right to try to reduce Channel crossings as much as possible. It is a dangerous trend, perpetuated by organised criminals, that puts vulnerable people at extreme risk. But the prime minister’s pledge to “stop the boats” completely is unrealistic. Nothing Sunak can realistically do will totally eliminate uncontrolled flows of migration into the country. The movement of asylum seekers is affected by many overlapping factors including geopolitical events and global economic trends that and no single piece of legislation can hope to resolve.

The government is keen to present the bill as a clear plan to deliver the prime minister’s pledge. But since its publication, the legislation has raised more questions than answers – about whether it adheres to the UK’s international obligations, how it will be interpreted and implemented, and whether it will work in practice.

The bill will now be subject to scrutiny as it passes through parliament. Given its importance and risk, the government should not rush the legislation through its stages to avoid detailed scrutiny. Without clear answers to the following questions, the new bill will fail to make a meaningful difference.

1. Does the bill adhere to the UK’s international legal obligations?

Within the legislation, the home secretary states under Section 19(1)(b) of the Human Rights Act that she is unable to confirm the bill is compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. This does not mean that it is necessarily incompatible, but that the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) may rule against the UK government’s policies. Braverman confirmed in a letter to backbench MPs that “there is a more [than] 50% chance” that it may be incompatible with the convention. 51 [1] Sleigh S, ‘Exclusive: Suella Braverman Admits Immigration Crackdown May Not Be Legal’, Huffington Post, 7 March 2023, www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/exclusive-suella-braverman-admits-immigration-crackdown-may-not-be-legal_uk_64072e62e4b0586db70fd939

This makes it highly likely that appeals will be lodged with the ECHR, which will need to adjudicate on whether the bill adheres to the convention, including on the rights to family life, freedom from slavery and torture. Any finding that the bill does indeed contravene the convention could ultimately lead to a confrontation between the ECHR and the UK government.

Separately the UN Refugee Agency, among others, have said that the bill breaches the UN’s 1951 Refugee Convention by preventing people who arrive irregularly a chance to seek asylum in UK, amounting to an effective “asylum ban” 52 UNHCR, ‘Statement on UK Asylum Bill’, 7 March 2023, https://www.unhcr.org/uk/news/statement-uk-asylum-bill (although enforcing against breaches of the Refugee Convention is difficult).

A group of people thought to be migrants are brought in to Dover, Kent, onboard Border Force vessel searcher.

2. How does the bill change existing policy on inadmissible claims?

This bill is not the first effort by the government to ban people arriving by small boats from claiming asylum. In January 2021 the Boris Johnson government introduced a rule to deem anybody who travelled to the UK via a ‘safe’ country including France (and so all those crossing the Channel, and the vast majority of other irregular arrivals) inadmissible for asylum. This was further defined by the Nationality and Borders Act 2022.

However while the government did not lack the (theoretical) power to remove people in these circumstances it did lack – in most cases – anywhere to send people. It is therefore unclear that the new legislation’s approach to inadmissibility will truly help it remove large numbers of people, in practice, where it was previously unable.

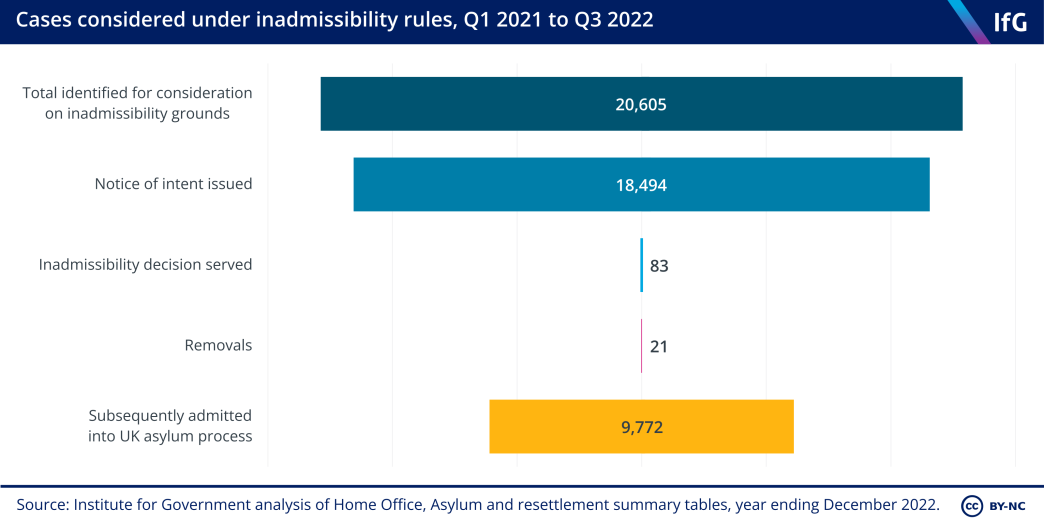

But the new legislation does change the application of inadmissibility in at least two important ways. Previously, if the Home Office has been unable to prove inadmissibility and/or remove an individual, the government’s immigration rules require that they be admitted into the asylum process, usually after around six months.

55

Home Office, Inadmissibility: safe third country cases, Version 7.0, updated 28 June 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/inadmissibility-third-country-cases

From Q1 2021 to Q3 2022, some 9,772 of 12,286 cases (over 75%) flagged as potentially inadmissible were subsequently admitted into the UK asylum process.

56

Although 33,029 people were detected as arriving in the UK via small boat in this period, the Home Office would not be able to provide evidence of a connection with a safe third country for all people crossing the Channel. ‘Potentially inadmissible’ cases refer to the 12,286 notices of intent issued between Q1 2021 and Q1 2022, as the Home Office’s guidance expects it to take 6 months to secure a removal agreement.

Under the new bill, people deemed inadmissible would be “permanently inadmissible in the UK”. As addressed below, this could have profound implications for people detained without prospect of asylum in another country or bailed from detention with no chance of securing asylum and no right to work in the UK.

The bill also changes how modern slavery claims are handled. Current Home Office guidance states that it is usually appropriate to pause the inadmissibility process until a modern slavery consideration is completed. But the new bill restricts the ability of people who have come to the UK irregularly to access modern slavery support, and stops most people using such claims to prevent their removal.

The government has done this in response to what it sees as abuse of the modern slavery rules to avoid removal, particularly by Albanian arrivals by small boat. As noted above, a majority of people detained for removal are referred as potential victims of modern slavery, and of those most are subsequently released from detention. But by banning these claims, the government risks depriving legitimate victims from receiving support and protection.

3. Where can the government send asylum seekers deemed inadmissible?

In theory, the government has several options for countries to which it can remove people whose claims have been deemed inadmissible. They can be sent to the country from which they travelled to the UK, provided it is deemed “safe” by the government. Certain European nationals can be removed to their home country; this includes Albania. Or they can be removed to any other country, provided there is reason to believe they will be admitted and the home secretary considers there to be no risk the person will be persecuted.

But in practice, the government’s options are extremely limited, which is why so few removals have been made in recent years.

The UK only has a limited number of removal agreements in place and, crucially, does not have one with France. It is no longer part of the European Union’s Dublin Regulation which enabled some returns between European countries. One option being tried is the government’s controversial deal with Rwanda to process asylum seekers who travelled to the UK in small boats. Removals to Rwanda however may not happen until March 2024 due to legal challenges, if at all.

59

Yorke H and Wheeler C, ‘Rwanda flights put back until 2024’, The Times, 5 March 2023, www.thetimes.co.uk/article/rwanda-flights-put-back-until-2024-xq8g9827k

And even if the scheme is enacted, the Home Office itself says the country has the initial capacity to process only 200 people, a number dwarfed by the more than 45,000 that arrived by small boat last year.

60

Gower M, Butchard P, McKinney CJ, The UK-Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership, House of Commons Library, 20 December 2022, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9568/

The bill gives the government the theoretical power to remove large numbers of people arriving in small boats. And in practice it will make it easier for the government to remove Albanians to their country of origin, which the government now deems “safe”. But it does not improve the government’s actual options for removing most people arriving irregularly, including those whose country of origin is not deemed “safe”. This would include people from Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Eritrea and Sudan, who made up almost half (46%) of irregular arrivals in 2022. Unless the government is successful in negotiating and enacting more removal agreements, the potential of this legislation to help is severely limited.

4. What does the home secretary consider to be a “reasonable prospect of removal”?

The Home Office’s current guidelines state that a reasonable timescale to remove people with inadmissible asylum claims is usually six months. 62 Home Office, Inadmissibility: safe third country cases, Version 7.0, updated 28 June 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/inadmissibility-third-country-cases, p. 28 It can be shorter, if no countries agree to accept the person, or longer, if progress towards a removal agreement is delayed. After this time, most people have been admitted into the UK asylum system.

The new bill takes a different approach. It allows for a person to be detained as long as is “reasonably necessary” in the home secretary’s opinion to enable the removal to be carried out. This will reduce the ability of the courts to decide what constitutes a reasonable period of detention, and empower the home secretary. The bill therefore potentially gives the government the power to detain most people indefinitely, although some may be granted bail by an immigration judge after 28 days.

It is important for the home secretary to clarify what criteria she will use to consider whether or not options for the removal of people from the UK have been exhausted. Specifically, she should clarify whether the government will continue to use a timeframe to make this consideration.

5. What will happen to people the government cannot remove to another country?

Without increased capacity to remove people, it is likely tens of thousands of people will arrive in the country by small boat, be detained and declared inadmissible for asylum in the UK, but with little prospect of removal from the country.

The government should urgently clarify its approach in these cases. Will most remain in detention and, if so, for how long and to what end? Some may be able to secure bail after the initial period of 28 days detention, but they will do so with no prospect of being admitted into the asylum system and no right to work in the UK – leaving little prospects and increasing the chances they experience poverty, destitution and require more acute (and costly) public services in the future. What will the home secretary’s responsibilities be to these people? Assuming they are eligible for accommodation and support, it will only add to the demand for, and cost of, hotel accommodation.

6. How will the government accommodate people it has detained and how will it pay to do so?

Alongside moral and legal issues, the potential of indefinite detention of large numbers of people is practically extremely difficult. The UK has a limited immigration detention capacity of around 2,286 people, according to the Refugee Council.

66

Refugee Council, The Truth about Channel Crossings, March 2023, www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/information/resources/the-truth-about-channel-crossings/

If everyone who crossed the Channel last year had been detained for 28 days and then bailed or removed, by 1 September a minimum of more than three times that number (around 7,500 people) would have been being held in detention.

Immigration detention also comes at a cost to government. In Q4 2022, it cost an average of £120.42 per day to hold an individual – if every person were detained for at least 28 days that would cost at least £3,371.76. According to Refugee Council analysis, it would cost around £1.4bn to detain all 65,000 people predicted to cross the Channel in 2023 assuming it takes an expected six months to arrange a removal, as per the Home Office’s current guidance.

67

Refugee Council, The Truth about Channel Crossings, March 2023, www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/information/resources/the-truth-about-channel-crossings/

And likely more as the bill applies to all people entering the UK by irregular means via a safe country, not just to those who arrive by small boat. While the Home Office is reportedly considering two former RAF bases for immigration detention use,

68

Swinford S, Wright O, Smyth C and Yeomans E, ‘Sunak plans annual cap on number of refugees’, The Times, 6 March 2023, www.thetimes.co.uk/article/sunak-plans-annual-cap-on-number-of-refugees-g9w9p73l8

it would likely need to open more sites to detain the people it will be obliged to remove.

The department will also need to consider how best to cooperate with local authorities in which these sites are located. Home Office takeovers of hotels have proven extremely unpopular locally, and councils have complained about a lack of engagement from the department. They will also need to take steps to avoid allowing these sites to become the target of far-right violence, as recently seen outside a hotel in Merseyside accommodating asylum seekers.

The Home Office would likely need to open more immigration detention sites to detain the people it will be obliged to remove.

7. Will it actually deter people from crossing the channel in small boats?

The bill states that by requiring the removal of people who arrive in the UK by irregular means, it aims to deter unlawful migration, particularly by dangerous routes. But there is little evidence to demonstrate that those willing to risk their lives crossing the Channel will be deterred by changes to asylum policy. This was seen with the Rwanda scheme in 2022, where again this lack of evidence led the Home Office permanent secretary, Matthew Rycroft, to request a ministerial direction from the home secretary on the grounds that the civil service was unable to confirm the value for public money. 71 Home Office, Letter from Matthew Rycroft to Rt Hon Priti Patel, 16 April 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/migration-and-economic-development-partnership-ministerial-direction

These are two examples of a long-standing belief in the Home Office, testified to by former officials, known as ‘pull factor orthodoxy’ – the idea that by making the asylum system more difficult to navigate, prospective asylum seekers are less likely to travel to the UK. But this long-standing orthodoxy has no basis in published evidence.

The Home Office has refused to release its own research into why asylum seekers come to the UK: the most recent publicly available study from the department is from 2002 and suggests that ‘pull factors’ relate primarily to the role of agents and asylum seekers’ connections to the UK, rather than the UK’s labour market and asylum policies. 72 House of Commons Home Affairs Committee (HASC), Channel crossings, migration and asylum, First Report of Session 2022–23 (HC 505), 2022, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/23102/documents/180406/default/, p. 29 The House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC) recommended that the department collect information on why asylum seekers come to the UK, “to form a sound evidence basis for future policy-making”. The Institute for Government has also argued that the department should publish its evaluation plan for the Rwanda scheme, to explain how it intends to judge whether a deterrent effect is achieved. The department is yet to do so.

Conclusion

The prime minister described the new asylum bill as a “signal” of his government’s position and intent, to stop the small boat crossings and prevent what it considers to be illegal immigration. It is certainly a signal (with a general election on the horizon). But it is much less clear that this legislation will make a substantive difference to the practical realities of asylum and small boats crossings.

The bill is based on an idea of deterrence – that a harsher system will put people off travelling to the UK – that lacks any robust evidence. It will be challenged in the courts and lead to a confrontation with the ECHR. Without increased capacity to remove people, classifying ever more arrivals as inadmissible will not help the government reduce the backlog or the money spent on accommodation – or improve public trust in the immigration system. And at a human level, it has the potential to cause serious harm to vulnerable people.

If the government is going to do more than signal intent and actually achieve its stated objectives, it should start by setting out clearer answers to the questions raised here.

- Topic

- Policy making

- Keywords

- Immigration

- Position

- Home secretary

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- Home Office

- Public figures

- Suella Braverman Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government