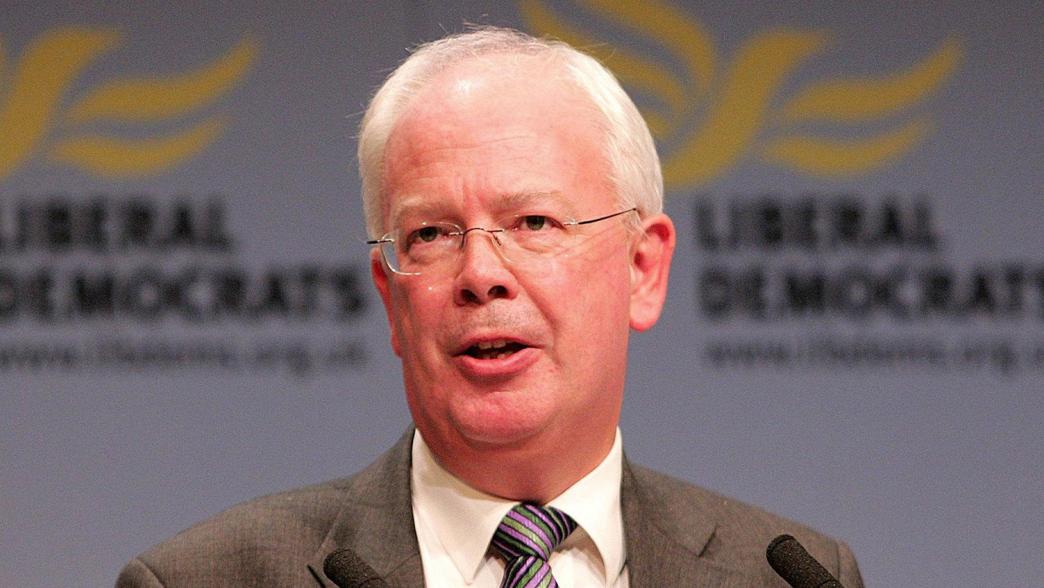

Lord Wallace

Lord Wallace reflects on his experience in the UK coalition government and how it compared to his time in the Scottish government.

Jim Wallace – Lord Wallace of Tankerness QC – was deputy first minister of Scotland, 1999–2005 and advocate general for Scotland (in the UK government), 2010–15. He was a member of parliament, 1983–2001, a member of the Scottish parliament, 1999–2007, and has been a member of the House of Lords since 2007.

Lord Wallace Minister Reflect on being in the Scottish government

Lord Wallace reflects on negotiating and managing the Labour–Liberal Democrat Coalition, using Scotland’s new powers for law reform, and representing Scotland in Brussels.

Tess Kidney Bishop (TKB): Going back almost 20 years to 1999, what was your experience of coming into that brand new government?

Lord Jim Wallace (JW): It was very odd given the circumstances. It wasn’t like if you’d come into government in Westminster. We were coming in a situation where we were negotiating a coalition, and also it was a completely new establishment. One of the first things that struck me after I actually became a minister, [after] it was agreed the coalition [Labour–Liberal Democrats, 1999–2003] would go ahead and I would be deputy first minister [DFM] and minister for Justice, was just how the whole machine then cranked into action. I was presented with a private secretary and the following day a press officer.

I remember that first weekend, a week after the election. We had finally agreed the coalition and signed it on the Friday. Eventually I got home to Orkney, which I hadn’t really been in since the count and the declaration at the election a week before. Not long back home and the fax machine, these are days of fax machines, starts going and you’re being given the diary for the following Monday, which was the appointment of ministers. By that stage I realised that I was no longer Jim Wallace, I was ‘DFM’. It’s a thing I’ve discovered, that acronyms go right through the civil service. I had meetings recently on the Brexit stuff with David Lidington, he’s ‘CDL’ [chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster], so then I realised that I was DFM. It was all the appointment of ministers: “a car will take DFM to Bute House [official residence of the First Minister], you will wait there and so and so will come along.” I had to go in with the First Minister and any of the Liberal Democrat appointments. The machinery was there, so it was slightly odd.

The first episode of Yes Minister is actually very, very good. He’s been told: “You’ll have your permanent secretary and you will have your parliamentary under-secretary and you’ll have a private secretary, this is your private secretary, this is your deputy private secretary”, and Jim Hacker says: “Do any of them type?” They said: “That’s why we have secretaries.” The other thing I discovered, which is again reminiscent of that first episode of Yes Minister – and I gave up, as Jim Hacker did – I said to my private secretary who was all “minister, this; minister, that”, “Call me Jim.” When Jim Hacker says: “Call me Jim”, Bernard says: “Gin minister, do you take tonic with it?” But someone took me aside and said: “Actually, it’s a matter of status to them that you are minister, you’re their minister.” So I just let it go. Very interesting, when I ceased to be a minister it was all very friendly and first name terms.

So these are just little things, but you were going into a system that was already fully functioning. Donald Dewar [then first minister] made it very clear to me in the first post-election meeting we had that he expected that the Labour Scottish Office, as was, would really just carry on with a few more additions and they would just incorporate the Liberal Democrats into it. I said: “That’s not how I see a coalition. We’ve got to have a partnership agreement, we’ve got to have agreement as to what our terms of agreement are.” And this came as news to Donald. But we’d thought it through, we’d done quite a lot of preparation…

AP: Not just watching Yes Minister?

JW: Not just watching Yes Minister, yes. Philip Goldenberg, he was a Liberal [Democrat] candidate in Woking in the ‘90s and a solicitor, he’d done quite a bit of work for Paddy [Ashdown, then Leader of the Liberal Democrats] in the ’92 election for if there were a hung parliament. He passed on to me all his papers, with good advice like the last thing you do is appointments. You agree the [policy] package first then agree some of the modus operandi.

AP: And you then carried that through to the coalition negotiations in 2010?

JW: Absolutely, we carried that through in 2010. I was giving Nick [Clegg] some advice as to what we’d done, the things that worked.

So they [the Labour Party] had to come to terms with the fact that there was then a programme for government. There was an attempt, not to change it as such, but to relaunch it in a different way, which we were quite sensitive to because I think we thought they might try and ditch things that they’d agreed. But we were ably helped by a particularly good civil servant called Philip Rycroft [then Deputy Head of the Scottish Executive’s Policy Unit]. He kept a look out and made sure that it actually went forward. There was a document launched in about September 1999, which basically was just a polished-up version of the partnership agreement.

It was quite interesting as an incoming minister to see all the briefing that had been done on our manifesto, it was very thorough.

TKB: So the civil servants were ready for that new level of political involvement?

JW: Yes, they had done a lot of work. In fact, they knew parts of our manifesto better than I did myself, with all the problems attached to it. I don’t remember detail on that but I do remember getting copious volumes of paper. One of the problems I had was that as deputy first minister, they took the view that I had to see everything and I had to sign off everything. I remember these first weeks, I was signing off every parliamentary question along with the first minister.

AP: From across the whole of government?

JW: Across the whole of government. Eventually I said: “This is nonsense. If there are difficult ones, if they raise important issues of policy with a coalition dimension, yes, send that to me. But I’m not going to spend my nights signing off transport questions about the state of the A86.”

"I’m not going to spend my nights signing off transport questions about the state of the A86."

AP: Do you think that a legacy of it having recently been a single department [as the Scottish Office]?

JW: I really don’t know what it was a legacy of, because I can’t imagine that the secretary of state signed off every PQ [parliamentary question]. Maybe he did, maybe there weren’t so many.

I think there was an effort to make sure I was treated the same way as Donald [Dewar]. If he was seeing it, I was seeing it. For the most part, that was quite honourably followed through. There were still certain things which only the first minister could do. There was one such case which Jack [McConnell] had to do but he’d had a constituency involvement and eventually I did it. I think it was signing off a mental health release. There were some things under the mental health legislation which were personally the responsibility of the first minister. It had been constituents of Jack’s, and Jack had made representations at some point. I’m sure it was legal for me to sign it off. He did ultimately sign it off but on the basis that I had looked at it and recommended that it be done.

They [the civil servants] were expecting a coalition. But the big difference between 2003 and 1999 was that in 1999, the civil service mindset when we went into the coalition talks before we went into government, was that they were dealing with the secretary of sate for Scotland [Donald Dewar] and two or three ministers: Sam Galbraith, Henry [McLeish]. We were like the supplicants. Fair enough in terms of party balance. But the point I tried to make [to] them was that actually, he is not the secretary of state for Scotland. He is the leader of the largest party in the Scottish parliament but he doesn’t have a majority. But everything was deference to the secretary of state. If we asked for briefing papers about beef on the bone or abolishing tolls on the Skye Bridge, they were all filtered through the Labour ministers before they came to us. Which I didn’t think was right. They were maybe just frightened to do it off their own bat.

By the time we came to the coalition talks in 2003, I’d been a minister for four years and I’d been deputy first minister, been acting as First Minister three times. Therefore, it was far more equal. We talked about it beforehand with Muir Russell [then permanent secretary to the Scottish executive] and there was parity. We had our own dedicated team of civil servants, the Labour Party had a dedicated team of civil servants. Jack and I took it in turns to chair the plenary coalition discussions. That was a much better process but that was a learning thing.

AP: But you ran the civil service by then…

JW: Yes.

TKB: You were also minister for justice during those years. How was it decided that you would do both roles?

JW: I always assumed that if I was going to be deputy first minister, I would also hold a portfolio. I think it was right. There’d never been a minister of justice before. We had a manifesto proposal [that] there should be a justice minister that brought all the things – police, fire, prisons, law reform – under the one roof as it were. And Donald Dewar and I agreed it. As I say, the last thing we agreed was personalities and positions, and when we got the agreement struck, Donald said: “Well, you’ll obviously be deputy first minister and I’d like you to be minister for justice.” I said: “Yeah, absolutely.” I was delighted. It is what I would have chosen.

TKB: How separate were the two roles?

JW: They were separate but your diary could be from 9:45am to 10:30am you were chairing a cabinet sub-committee in your role as deputy first minister, and at 11 o’clock to 12 o’clock you were meeting the head of the Prison Service. They were intertwined and that’s a good private office. I was very fortunate I had a good private office. I think my private secretary was probably handpicked because he was very, very good.

I’m not kidding, it was a pretty heavy workload I can tell you. Especially those first weeks when I was also clearing transport questions, agriculture questions and health questions. But I mean we got a good modus vivendi eventually. I think the thing about being deputy first minister, and sometimes the party used to say I should have done more, is that you could roam widely over other portfolios. You had to be careful that you didn’t tread on too many toes. The party used to say: “You should have a higher profile on this health issue or that health issue”, which is probably right but you just had to be careful how you did it. I think it was important that I did a portfolio, because it got me a profile on other issues.

"I think the thing about being deputy first minister… is that you could roam widely over other portfolios. You had to be careful that you didn’t tread on too many toes."

It was not always very easy. The first big thing that came along was when [Noel] Ruddle got released from the state hospital in Carstairs by the Sheriff in Lanark, albeit that he had shot his neighbour with a Kalashnikov. All hell broke loose and we had to do emergency legislation. This was the summer recess of 1999, we had just taken office and the media just wanted the coalition to fail at times I felt. I was a target for attacks for not being on top of it. All I can say is that the first bill we took through the Scottish parliament was on mental health appeals [Mental Health (Public Safety and Appeals) (Scotland) Act]. It was subsequently challenged all the way to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. And one of the justices of the Privy Council said: “This crisis, emergency, hit the Scottish ministers when they were only weeks into office. They acted with commendable haste and efficiency, introducing a piece of legislation which we are happy to say is proper.” That’s not quite how they put it, but it was an absolutely glowing testimony to new ministers who had just taken office in a completely new system and how we’d actually done it and got it right.

AP: Was it challenged on human rights grounds?

JW: Yes. But I was always quite amused that that [positive] judgement never appeared in any newspaper headlines. It was a challenge, but it did give me a profile. Right throughout you got a profile, you were meeting police… It’s no longer the record now, but at the time we reached record police numbers. There was always some issue. We had a programme of law reform, reforming the feudal system, a white paper on family law.

AP: In your role as justice minister, did you identify two or three central priorities? Presumably there were things in the coalition agreement.

JW: Yes, there were things in the coalition agreement but it was doing them. Then, we did have a target of trying to increase the number of police. Within weeks, I made sure I got responsibility for implementing Freedom of Information in Scotland, which had been one of my commitments. In hustings, when they asked: “If you win the ballot for the private member’s bill, what would you do?” I always said: “I’d deliver a Freedom of Information Bill.” So I actually got to deliver, and took through the Freedom of Information in Scotland Act. There was a programme of law reform which I was very keen on. Apart from the mental health one, which we had to do as emergency legislation, the first substantive piece of legislation that was introduced was the Adults with Incapacity Bill. That was a Scottish Law Commission bill which I remember being lobbied about it down here [in London] and saying: “Look, when we have a Scottish parliament, we’ll have time to do that sort of thing”, and I made sure it was the first bill. We did land reform, which was then my responsibility; it transferred two or three years later to Environment and Rural Development. There was the whole abolition of the feudal system. England had done it in 1290, we got round to doing it in 2001! There were laws relating to tenements. There were a number of law reform measures which the Scottish Law Commission had produced reports on.

AP: One of the cases made for devolution was that Westminster just never had the time for Scottish business, so it’s partly clearing that backlog. Were some of those particularly politically contentious as well or were they mostly quite widely supported?

JW: We had a majority, with Labour. But interestingly, although we had a majority – and I think this is where the Scottish parliament has changed since I left, at the same time the SNP [Scottish National Party] came to power – the committees were far more effective in holding us to account. I would get a rough time. Sometimes I got a tougher time from both Labour and Liberal Democrat members on the committee than I would get from opposition members. And that was fine. I used to say: “Fine. If we listen to you and we change, this is not gloating that the government is doing an embarrassing U-turn, that’s how this parliament is meant to work. We will scrutinise and if you can persuade me that we’ve got something wrong, or it could be better done in this way and not that way, that’s how it should work.”

A very early example of that was when I had responsibility for the census in 2001. These are the sorts of things that came under the justice portfolio, I was also responsible for which days flags were flown on public buildings. This is an interesting thing about coalition trust: Donald Dewar within the first few weeks of government, said he would like to see me. He said: “This is very sensitive but the prime minister wants to hold an election on the first Thursday in May next year and that will only be four days after the census, which you’re responsible for by the way, and we’ve got to work this through because some people are questioning down south as to whether we can; if you’ve got people coming up garden paths to take census information they might get confused with people knocking on doors.” So he told me 10 months out when the prime minister wanted to hold the next general election. I never told that to any of my Lib Dem colleagues because I thought it was a matter of trust. I then had to engage with the Registrar General and we reckoned that we could actually do it. As it happened, the whole thing got knocked off course by foot and mouth [disease] and we had to then at a very late stage work out how we actually accommodated the foot and mouth outbreak.

"So he told me 10 months out when the prime minister wanted to hold the next general election. I never told that to any of my Lib Dem colleagues because I thought it was a matter of trust."

It still frustrates me today because things go wrong in Scotland, rural payments are scandalously late and things like that, and the media are not up on it. But we knew full well that if anything went wrong on that census… They wanted to bring down an institution that they’d spent so much time building up. I knew full well that the census had to go without a single hitch. Of course it did, which you never get any credit for. But if there’d been a problem with it, cor blimey, you could imagine the heavens would have fallen in on us.

But there was a move to have a religion question in the census. All the advice I got was that every question in the census costs a lot of money, by the nature of the beast, and it would cost a lot to add another question. And no one could see any useful purpose for the information that would come from this, other than “interesting to know”. So I went before the Equalities Committee and strongly resisted. By then I had been told, if you needed a religion question, you had to change the 1920 Census Act, primary legislation. There were one or two things [that] could be done by order but because it was a completely new category, it would require primary legislation. So I took it to the cabinet. It’s the only time I ever remember a hands-up vote in the cabinet. It was a hands-up vote in the cabinet deciding not to do it. So I defended that decision before the Equalities Committee and they produced a unanimous report saying there had to be a religion question in the census. After we lost in the Committee, we clearly reversed it, the government changed its position. Now I just don’t think that happens today.

AP: Wouldn’t you have been asking the same questions as in the rest of the UK in the census though?

JW: No. It was a devolved matter, so we could ask different questions. Some things were different. And I think there was some suggestion that they were going to move towards questions on religion in the UK as a whole, as they have done since.

I remember when we got the results on language, saying to the chief executive of Orkney Islands Council: “There’s more people who speak Gaelic in Orkney than I thought.” He said: “Yeah, read down the small print and there’s five people who travel to work by train every day.” Which is complete nonsense, there aren’t any trains in Orkney!

But the point I was making was about the committee. It was a robust system.

AP: That’s interesting that even when you had an agreed government position sometimes you had to then change the position. Going back to your role as deputy first minister, how did you and the successive first ministers work together. Did you jointly manage the team of ministers across the rest of government?

JW: Yes. They all got on and did their departmental jobs. We had weekly cabinet meetings. If there were problems, they would pretty quickly escalate to first minister and the deputy first minister. A number of times there were crisis meetings with the Liberal Democrat group, because I always took the view that I wouldn’t sign up to anything unless I knew I could carry it. There’s no point me saying to the first minister “Yes we’ll do this” and then going back to my group and finding that that there are three of us supporting it and 13 against. So it was quite painstaking at times on certain issues to try and make sure if I went into a room and said to the first minister whichever policy it was, “Yes, we can do this,” that I was fairly certain that I actually could carry my team. There were other times where I said: “Well, I can’t do this”, and that went to a real negotiation.

I remember on issues like the abolition of what in Scotland was Clause 2A and in England was Section 28, and there was a huge outcry in Scotland and petitions. We were quite adamant. Part of the problem was that Wendy Alexander [then minister for communities] had announced that we were abolishing it without actually consulting anyone. It wasn’t in the programme for government, it wasn’t even in our manifesto I don’t think. But she announced it, of course without consultation – there should be a lesson there. But we were quite determined that we were not going to backtrack. And on our side, we were absolutely solid. The Labour Party were a bit divided within the cabinet and I remember Donald and I jointly holding a meeting of key ministers from across the government. We would just try to thrash it out, what actually we would say, there was some guidance that was going to be given to schools and things like that. So when issues like that arose we would tend to act jointly. I say jointly, Donald was first minister, he chaired it.

AP: Would he always chair?

JW: He would always chair it on these ad hoc sorts of meetings. There were some committees that I chaired. But on issues where we were having to try and thrash out a policy position with conflicting ministers, he would chair. On that occasion, everyone on the Lib Dem side was signed up, but it didn’t always happen like that. People used to think we were weak in government because anything that came up, there were two Lib Dems in the cabinet and we would always be outvoted [by] nine. But it never happened like that. There were many divisions within the Labour Party. It was proper collective government. We had an internal debate and sometimes they were quite feisty debates. But very rarely did we split. And that was the benefit also of having the coalition agreement. But people thought that we were supine, because obviously if anything came up we would lose seven-two. That’s just not how it worked.

"It was proper collective government. We had an internal debate and sometimes they were quite feisty debates. But very rarely did we split."

AP: What did you do as deputy first minister to ensure that, not only were Liberal Democrat policy priorities followed through, but that your party profile was maintained, that you were getting credit externally for not, as you say, being supine and giving in?

JW: I think partly the fact that I had the profile on justice issues helped. Ross Finnie was the other full [Liberal Democrat] cabinet minister as rural affairs minister, and given the nature of a lot of our seats, there was a profile there. He was out and about at agricultural events. On issues like tuition fees, we actually got a good outcome. The fact that, to all intents and purposes, we prevailed on that and got Labour on board, it was seen as a positive Lib Dem thing.

I remember Donald on the first anniversary [of being first minister] was asked what were the things that he was most proud of doing. I think it was tuition fees, Freedom of Information and a third thing I can’t remember, but they were all Liberal Democrat things from the coalition agreement! The fact that we had rows over things like tuition fees, certainly at the outset we had a few, and then in 2001 over free personal care for the elderly, and then latterly after 2003 on STV [single transferrable vote] for local government elections. These were big things which we badged as ours. And the opinion polls often gave the Labour Party credit for them, but a hell of a lot of people give us the credit for them, probably more people give us the credit for them than voted for us.

AP: In the 2003 election, you actually gained proportionally compared to Labour.

JW: Proportionally we did. We lost one seat I think.

AP: Conversely to what happened to the Liberal Democrats in 2010. Did you ever feel a need to play up the differences at times?

JW: I don’t think we manufactured them. And that’s quite an important thing. The nationalist opposition, very early on, thought they were on to a good thing by, on their opposition days, tabling motions or tabling subjects for debate on issues which we were divided on at Westminster – which was daft.

The first time this happened of course there was great crisis. I said to Donald: “We should actually lose a vote or two. There’s no harm if we lose a vote, if it’s a non-binding opposition motion, it won’t matter. But if you hold it off until we lose one it will be a big thing.” We will lose and that’s fine. Let’s be clever about it. We don’t need to put up an executive spokesman, these are reserved matters, joining the Euro or something like that. So does it matter that there’s no government policy on this? There’s no coalition view on this. We don’t need to take a view on it. The civil service didn’t like that. Every debate had to have someone replying from the executive. I said: “Well, why? This is not a matter of collective responsibility.” Sometimes what we would do is people would just speak, we would put someone up. But often we would tag on an amendment to the nationalists’ amendment, saying: “Notes that the Labour government is doing X and the Liberal Democrat opposition believes Y.” Because that was factual, we could all vote for it. The nationalists persisted in this for longer than I thought but we eventually saw them off on that. And that suited us.

Let’s remember the big issue was the Iraq War in 2003, which was in the run up to the election. If you look at the really good debate we had, Jack McConnell led off for the Labour Party, I spoke for the Liberal Democrats and we made party speeches. I used to say: “There’s no way I’m going to slag people off.” It was all done in a fairly measured, constructive way. You couldn’t go into a cabinet meeting one morning and slag them off publicly the next. It just wasn’t my nature and it wasn’t right. But it did give us a profile. And it allowed us to be in opposition in London and in government in Scotland.

"You couldn’t go into a cabinet meeting one morning and slag them off publicly the next."

AP: That’s really interesting actually. How did your working relationship with the three successive first ministers change?

JW: I find that difficult to answer. Because they’re very personal things. It’s not that I don’t want to deal with the personal, but it’s dynamic.

I probably felt more of an equal with Henry and Jack than I did with Donald. That was a product of the fact that he was quite a bit senior to me. He had been a cabinet minister. I didn’t allow that feeling to detract from what we were trying to achieve or from my duties to my own party. And it was quite a close relationship with Donald. If anyone could have a close relationship with Donald. He was a complex guy, but we got on well together. I don’t remember any real fall outs. We’d have differences but they were always well managed. There were little things. When I was talking about this guy that got let out from the custody of the state hospital and I was having one hell of a time with the media, and Donald discovered it was my birthday. He came through and he said he’d been at the Tunnock’s factory in Uddingston and they’d given him a box of 144 caramel wafers, and he came through and gave me a caramel wafer for my birthday.

Then, when he knew he was going to go into hospital for tests, it was running up to Easter, they said he’d like to speak to me. So I went in and he told me about his medical condition and he was going to have to go into tests and likely that would lead to him going in for major surgery. He said: “Of course you’ll take over”, and I said: “What?” He said: “Yes, you’ll take over, chair the cabinet.” I said: “I don’t remember this being in the script”, he said: “Deputies deputise.” And that was it. So he had that trust in me, which I think mattered to me. When he died, it also mattered to the Labour Party too because they agreed that I should act as first minister until they elected a new leader. It wasn’t automatic, they had a meeting. A Labour minister in the cabinet then came to me and said: “Would I do it?” Then again, after Henry resigned. But it was getting to be habit at that stage.

With Henry, I’d been in parliament longer than him at Westminster, although he had been a minister in the UK government. But I’d been deputy first minister. There was always a slight needle between Henry and I because he had expected to be deputy first minister. But personally we got on okay. We had the big issue over [free] personal care, which he wanted and he wasn’t quite sure his Labour colleagues wanted it. So actually he was quite happy for me to lead the charge.

AP: And it was controversial at Westminster, wasn’t it?

JW: Yes, it was controversial at Westminster too. But Henry wasn’t Donald. I just can’t put my finger on it, the dynamic. It was a perfectly good working relationship for the government of Scotland.

With Jack, it was different again because Jack and I had worked together on the Constitutional Convention. And just because it just went on longer. It was an easier relationship with Jack than it was with Henry. But I believe they were all good productive relationships.

Jack and I we decided that we really should have a fortnightly breakfast meeting just to catch up and that worked well. We wouldn’t have the civil servants in, just the two of us. The problem was, say what you like about the civil servants, the fact is if we didn’t have civil servants in, by the following day neither of us could remember exactly what it was that we’d agreed! So we used to have breakfast then we used to call an official in and say a, b, c, d.

AP: That’s probably a good idea! So neither of you would feel betrayed by the other by mistake. So then in 2003 you won another majority collectively. Was there any doubt that you wanted to carry on working together?

JW: There was never any doubt.

AP: But your role then changed. You shifted to Enterprise and Lifelong Learning. How did that come about?

JW: I think both Jack and I took the view I’d done justice for four years…

AP: You’d done justice to justice.

JW: Yeah, I’d done justice to justice. The latter part of that I also did Europe and External Affairs. If there was another portfolio I wanted to do, it was Enterprise and Lifelong Learning. And that wasn’t a problem. Jack was very amenable to that.

The biggest problem we had putting that government together was, as you mentioned earlier, the slight balance in the numbers had changed and I thought we merited another cabinet minister. He [Jack] was a bit iffy about it. We had a very clumsy compromise which resulted that Nicol Stephen [Liberal Democrat MSP] would be in the cabinet [as Transport Minister] but would be paid not as a cabinet minister but the next rung down, a junior minister salary. That’s how we got the three. And Frank McAveety [Labour Co-operative MSP] was in the same position vis–a-vis culture, media and sport. So there was a sort of a trade-off on either side. I’m sure after some time we just decided it was sensible to make them fully paid cabinet ministers.

TKB: How did the institutions evolve over your six years in government? Were they working effectively?

JW: I think they were. As I said, the processes for the 2003 coalition discussions were materially different from 1999. That was a major change. We were recognised as full players and had our own team of civil servants supporting us in negotiations as the Labour Party had on their side. So that was quite material.

I think the system became more used to coalition government. The fact that the Liberal Democrats always needed to have a group meeting before they could sign anything off became almost part of the flow of the place. But I still think, at the end of the day, the civil service is more comfortable with a single party. They, quite properly, deferred to the first minister but sometimes I felt they deferred to the first minister in a way which didn’t remember that there was a coalition dimension to it. Don’t ask me for examples, but at the time it was something we used to talk about in our group of Lib Dem ministers. I don’t think that’s a fault of the first minister, it’s just the system. That’s why when the SNP came in 2007 and Alex Salmond was undoubtedly the first minister, there is no one but him, I think they quite relished that. They were getting a clear steer and direction and not one that had to be mediated through two different parties. I certainly don’t complain about the service I got as an individual, as a departmental minister or indeed the support my office got. And over time we did increase the support of my office, because of the recognition of the added workload that I had. I don’t complain about that at all, but I still think that the system is more comfortable with single party government.

"But I still think, at the end of the day, the civil service is more comfortable with a single party."

TKB: When the SNP did come in, there were changes to the structures of the Scottish government. Had you been thinking about what that next phase of devolution might look like when you were in office?

JW: Not really, not when I was in office. I think when I was in office we felt very much that we need this to bed down. It was quite a big thing to do, to start with a clean sheet. It was a clean sheet in one respect, it wasn’t in another, as there was an administration there. The schools were still going to open the day after.

But especially given the fact that we lost two first ministers, there was quite an upheaval too. In some respects, I think that actually helped consolidate this, that we were able to survive two crises like that. It’s not circumstances anyone ever anticipated nor indeed did we want by any stretch of the imagination, it was pretty devastating. But the show went on, we didn’t move away. And the fact that we had a programme for government also meant that any incoming new first ministers, it happened both with Henry and then with Jack, came to our Lib Dem group and said that they personally endorsed the programme for government. That allowed us, when a vote took place for the first minister, to vote for both Henry and for Jack.

I wasn’t long out of the parliament when I was put on the Calman Commission [on Scottish devolution]. When the Nationalists won, clearly people did sit then looking at the settlement and they had their ‘national conversation’. So I then spent another year of my life looking at it. I tried to resist going on, just when I thought I was out of the woods. But when the prime minister [Gordon Brown] phones you personally and says “Jim, you must do it,” it’s difficult to say no. I could have said no but…

TKB: So by 2005 did the institutions feel bedded down?

JW: They did. And the Calman Commission then took up for at least a year. Then of course there was majority government, which we never anticipated after 2011. By this stage, I was in government here [in Westminster] having to work out what we did in terms of Section 30 orders [to devolve to the Scottish parliament the power to hold an independence referendum].

TKB: Again thinking about the changes the SNP later made, did you feel you were able to work across departments in those years? Could you pursue strategic objectives across them?

JW: I think so. Some of the sub-committees I chaired were on cross-cutting issues. I chaired one on tourism, one on flooding. There were a number of cross-cutting measures – that was the expression we used. But I think on the whole it worked.

AP: It’s interesting because after the SNP came in in 2007, that was at least presented as quite a major machinery of government change, when they moved to a non-departmental structure. It was just directorates who were supposed to be able to work together in a more flexible way within a single sort of organic structure.

JW: I wasn’t close enough really to see whether it worked or not.

AP: But when you were there with departments in a more traditional sense were you able to work in a cross-cutting way?

JW: Yes. It was small enough, so you could do things informally.

TKB: How were you managing the relationship with Westminster during this time? Was that more informal or formal?

JW: It was formal and informal.

Obviously I had my party relationships. It helps that Charles Kennedy [then Leader of the Liberal Democrats] and I were good personal friends. I, at one stage, suggested to Charles that we should have a regular phone call and he said: “No, I know you well enough and you know me well enough. If we need to speak to each other, there isn’t a problem, we just lift up the phone and we speak to each other.” I would see him or see some other colleagues on a fairly regular, if not on a planned, basis.

Then in terms of UK government, we did have regular meetings, as and when. Initially it was all ‘get to know you’. It’s something which I reflected on at the time and I suspect now it’s even more problematic, that UK and Scottish ministers, after devolution, would not necessarily get to know each other so well. In these early days, because I had been a Westminster MP, I knew a lot of the Labour ministers. Clearly we weren’t in the same party but I’d been around. I was Justice Minister when Jack Straw was home secretary, and I didn’t need an introduction to Jack Straw. We hadn’t known each other all that well but we certainly knew who each other were, and where we came from and things like that. I remember once having to go and see Derry Irvine [then lord chancellor]. But we did it on a departmental basis. As Justice Minister, I would engage with Jack Straw. We tried to have a policy of ‘no surprises’ and that worked.

When I was Enterprise and Lifelong Learning we had a number of difficult issues. Alan Johnson was a junior minister dealing with higher education when they were doing the top-up fees, and he talked to me on a fairly regular basis. I talked to him and Charles Clarke [then education secretary] because we said we would have to increase fees for English students. We were trying to keep them informed of what we were doing, because what they were doing was having a direct impact. If they started charging significant fees in England, there was every chance that people would just come streaming across the border to take up Scottish places. So we had to try and work through that, we had our own Higher Education Review to try and address that.

TKB: Were there any issues that were particularly difficult to work through?

JW: No. I personally didn’t deal with it, but the introduction of free personal care was an issue which was very difficult because we reckoned we were saving the UK government money and we thought that the financial Memorandum of Understanding meant that we should get some money back. But Alistair Darling as work and pensions secretary just wouldn’t hear of it. I wasn’t doing the negotiation on that, I think it was Henry [McLeish]. But there was a friction there.

I had an issue with Jack Straw, I think about police checks, vetting checks. We did something to the fee structure which he wasn’t very happy about. Also, what Jack was not happy about was that we brought in a Human Rights Convention compliance bill [the Convention Rights (Compliance) (Scotland) Bill]. I was fairly certain that we had to do something about indeterminate life sentences, so we changed that and brought in the notion of a ‘punishment part’. It basically made it possible to have a ‘life is life’ sentence, though you could still give a punishment part which exceeded the person’s likely life span. I know Jack was opposing a case before the European Court of Human Rights at the time, I think it was the case that he didn’t think we were being very helpful. There was never any ‘aggro’, but he made it very clear he wasn’t happy with it. The most recent case which did actually deal with it, came up with the European Court when I was Advocate General [in the UK government], to my wry amusement. They made passing comments about the Scottish situation, which they thought had judged it probably about right. But the English courts were being told they hadn’t quite got it right.

AP: You mentioned the tuition fees. Was there no resistance to that decision that you’d be increasing fees for English students even while you couldn’t for EU students?

JW: We had to do that. That was law, so we couldn’t do anything about it. I think we made it very clear that if we could have done something about it, we would have done something about it. It was quite interesting that the SNP have huffed and puffed about it, and again they’ve still not been able to do anything about it. I went to see Charles Clarke and just set it all out and he didn’t seem that bothered. I remember coming out and my official said to me: “Do you realise we’ve just got an extra £10 million out of the UK government today?” Then we thought, we don’t think they realise what they’ve done. He saw what we were saying. Going back to the original decision on tuition fees, Tony Blair did call us in, Donald and I went to see the man. And he wasn’t very comfortable with it. But then we said: “Well, that’s devolution, Tony.”

TKB: So you were briefly minister for Europe, but how involved were you with the EU over the whole period?

JW: Quite a bit. As I say, I had a spell when I was EU and external relations minister. That meant I went out to Brussels because we had a Scottish government office there. Then when I was enterprise minister I had a number of meetings, I once had a meeting with Michel Barnier [then European Commissioner for Regional Policy, now the EU’s chief negotiator for Brexit].

TKB: Were you able to get the Scottish position out there?

JW: Yes, but you had to be very careful that you didn’t undermine the UK position. On things like Regional Development Grants, we had a particular view which was not necessarily at one with the UK government view. It was quite challenging how you put that over. Actually, after one particular meeting, the EU Commission put out a statement which did suggest that we had taken a different position. My saving grace was that we had an UKRep [UK Permanent Representation to the EU] member in the room with me and he knew full well that I’d not transgressed. But we were conscious, because it was a partnership. At the end of the day, the UK government were the member state. I think the challenge was to get the view across that didn’t hole the UK case below the waterline but to make sure the Commission knew that there were particular issues of importance to Scotland.

More often when I was the justice minister, I attended EU Councils.

AP: With the UK minister as well?

JW: With the UK minister. There was one occasion where an issue had more salience in Scotland than it did in England, and I remember David Blunkett [then home aecretary] saying: “Well, you may as well take the lead on this.” So I sat at the table and Blunkett sat behind me. Actually, we probably sat together but I did the speaking. And Blunkett was totally relaxed about that.

AP: But you had agreed the position beforehand?

JW: Oh, yes. That was the whole point, we agreed the lines. That was particularly important. Not that I was personally involved but I had a close constituency interest in the agriculture and fisheries stuff. Ross Finnie often at these meetings, particularly around the Fisheries Council in December, would undertake a number of bilaterals.

AP: Subsequently, since the SNP came into power, that has been a point of contention, hasn’t it? Whether the Scottish minister for fisheries could speak in the Council of Ministers?

JW: Yes. I think there were times they were invited to lead. Certainly, there was at least one occasion when Nicol Stephen led the UK without any UK minister present on an Education Council, because both UK ministers were unavailable. So it was quite handy they could just send a Scot over. But again the line was agreed. And it’s all a question of trust.

TKB: Given what you’re saying about the importance of trust, what is your advice to the Scottish ministers at the moment for managing the relationship with the UK and the EU?

JW: I think as things stand at the moment, we’re in a completely different position given that we are negotiating coming out. I don’t believe that the United Kingdom ministers are living up to what they said at the outset of proper and full engagement with Scotland, Wales, and unfortunately there aren’t Northern Ireland ministers. If you go back and look at what they said way at the beginning [of the Brexit process] about involvement, I don’t think any of that’s happened, or very little of it has happened. A fair bit has happened at official level, but I don’t think much has happened at the ministerial level and that’s just wrong. But then, they can’t even get agreement amongst themselves I suspect. That’s a political point I’m making but I think it’s a factual one too. It’s something I must check out more. I was at a meeting way back in January with a guy from Canada and he said that in their Canadian CETA [free trade agreement between Canada and the EU] negotiations, there was usually someone from the provinces, and even the territories, present in the room at a lot of these negotiations. I’ve raised it on the floor of the House [of Lords] two or three times now and said: “When we do all these trade negotiations in the future, will there be any Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland ministers, or officials, present in the room?” The answer is there have been none.

"I don’t believe that the United Kingdom ministers are living up to what they said at the outset of proper and full engagement with Scotland, Wales, and unfortunately there aren’t Northern Ireland ministers."

AP: Indeed in future negotiations and the Brexit negotiations themselves. I remember in July 2016 in Theresa May’s first week as prime minister, she went to the three devolved capitals and said in a joint press conference with Nicola Sturgeon: “We’ll seek a joint UK approach and objectives to Brexit before triggering Article 50.”

JW: I think actually under the press release that accompanied the first ever meeting of the Joint Ministerial Committee on European Negotiations [JMC (EN)], it was all full of doing things together.

AP: That was the language that then found its way into the terms of reference for the JMC (EN) but it doesn’t seem to have happened in practice.

What would be your advice to ministers in the Scottish government or a future deputy first minister?

JW: There is a difference between a coalition and a single party government. The nature of my job was trying to make sure a coalition worked and that’s a different nature of job to the current deputy first minister. I think, in that sense, any advice would not be particularly pertinent.

If a future coalition was to come about, I think my advice to a deputy first minister would be to make sure that there is a good bond of trust between the first minister and deputy first minister. A recognition by the first minister too that you’ve got a party to lead and it’s not single party government. There will be times that there are differences but these have just got to be managed in a grown up and mature way. You can, most of the time, work through them. Also I would say, make sure you bring your party with you. Which is maybe where we made a mistake on tuition fees at Westminster.

AP: You’re talking about the wider party membership as well as the parliamentary party membership?

JW: Yes. Again, it’s easier in Scotland. The size of the Scottish party is much smaller than the size of the UK party. But you’ve got to start with your own troops in parliament, because they’re the ones you want to impress and have the support of.

TKB: What would your advice be to Scottish ministers on negotiating with the UK government?

JW: I think when it comes to negotiating with the UK government, you’ve got to try and make sure that there are no surprises. You’ve got to try and build up the kind of personal relationships which go beyond politics. I think, too, that you’ve got to be very clear on what you want, make sure you’re well briefed and you know your case. But it is a matter of give and take and it does require a lot of trust. I think that’s possibly where we’ve had some problems in recent times.

Lord Wallace Ministers Reflect on his experience in the UK coalition government

Lord Wallace was also interviewed for Ministers Reflect on 17 July 2015. He reflects on his time in the UK coalition government and how it compared to his time in the Scottish government.

Peter Riddell (PR): Can we start with Scotland? When you became a minister in 1999, given you were starting a new administration in every sense of the term, what support was available and how much had you thought about actually being a minister given all the run-up and everything?

Lord Jim Wallace (JW): In terms of support, it was civil service support. I think because I was deputy first minister I had a first-class private secretary. I can’t remember now how many people there were. I mean I had a bigger private office than other ministers because I was deputy first minister and I was also minister for justice, so I was given a bigger private office which I think in later years got a bit bigger still. I had a press officer and a deputy press officer who were partly for me, and partly for the justice department, and after two, three months, I had a special adviser, and that increased over the period I was there to three. It went up to two, and then went up to three. Donald [Dewar], our Labour first minister had nine.

PR: Was there any sense when you took over of an induction process?

JW: No, no. It was a real – the trouble with fax is that they actually fade, but I did keep the first fax that I got sent through to Orkney. We signed the coalition agreement on the Friday and then I went back to Orkney on the Friday afternoon. I then got this fax over the course of the weekend to tell me what was going to happen on Monday with all the new ministers, because they were all appointed after Donald and I had signed it. By that time I had become DFM [deputy first minister] to civil servants – all these acronyms. ‘At 2:15pm, Mr So-and-So will be picked up by his car and be brought to Bute House’.

But what happened was, Donald and I had a chat and I met my principal officer, a civil servant – I can’t remember what grade they were – Hamish Hamill, he was there to meet me and shake my hand after I came out of the room with Donald and that [happened for] every minister, and the head of department was there to greet them. And that was basically it. We were operating in Saughton House at that time at the justice department. And they took me to the new ministerial office and told me they were ready to repaint it. And I said, ‘Oh!’ It was a mindset, you know, they said, ‘We’ll repaint it for you’ and I said, ‘There’s nothing wrong with what’s here, you know’. It wasn’t repainted.

PR: After taking office, what was the most surprising thing about being minister?

JW: Well let’s go back and answer your previous question; I hadn’t really given it terribly much thought, because it was full-stage political campaigning and I don’t know whether I didn’t want to tempt providence by, you know, if you start thinking about being a minister before you got there, you might take your eye off the ball.

What was the most surprising thing? I tell you, the most surprising thing was I was extremely impressed by the extent to which they had gone through the Liberal Democrat manifesto and had briefings for me on just about any aspect of the Lib Dem manifesto, so it was very thorough. Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised; in retrospect I’m not surprised, but at the time I was surprised and impressed.

PR: In a sense like all England ministers, many of your roles had been done by one person in the past when it was the pre-99 structure. So in a sense they were kind of breaking it down to many more…

JW: Well that’s right. We were virtually creating departments in something that had previously been a lot more of a whole. Well it still was, what’s it called, the Scottish Home and Health Department, that was probably ‘94, ‘95, but we’d never had a department of justice before. I mean Henry [McLeish] who had done home affairs included aspects of the justice department, but it was the first time we’d actually had a justice department. And then of course we had two ministers; I was justice minister but I had a deputy, and that was replicated across the system.

PR: Looking at how your day worked, how did you manage your time? Because this is where we’ll come onto the contrast with London. Given that the parliament had a very central role because of the committee structure, how did you allocate your time?

JW: It was probably driven by events. I would probably be in the office, most mornings I’d leave the flat at eight, be there by about quarter past eight. So mornings tended to be in the department; in the first year, 18 months, my … justice department was in a separate place from St. Andrews House, but I probably spent more time in Saughton House on a Monday morning when I flew down from Orkney because it was en route into the city so I spent Monday mornings there. And then when parliament was sitting, each minister had an office in the parliament building. In the first year, [in] what was the Midlothian County Council is now the Missoni Hotel… and then latterly when we moved into the new building, there was a ministerial block, a ministerial floor in the new building, and we had an office there. And you know you might be a departmental minister and meet people at parliament, because that’s where you were based, and then when I say ‘driven by events’, if you were giving evidence to a parliamentary committee in the morning, then you shifted your office to the parliament. So I suppose the answer to your question is we actually had offices in each [place]. Latterly the justice department – because a lot of refurbishment had been done at St Andrews House at the time – came into St Andrews House. When I was a minister for enterprise and lifelong learning it made life slightly more difficult because my departmental office was in Glasgow. You always wanted to spend time, but I couldn’t do it the days parliament was sitting. I therefore would probably do Mondays… I look back… more often Fridays, I was there Friday mornings – or you were going out and about, you were going for visits, that was the other dimension to it. You had quite a lot of visits out.

PR: So you had your constituency over the weekend?

JW: I had my constituency over the weekend, yeah.

PR: Which you obviously knew very well anyway.

JW: Well for the first two years I was still a member of parliament. So occasionally I would come down here; there were occasions when Donald and I stood on the steps of St Andrew’s House and said, ‘This is daft, let’s pair’. But I was also MP for Shetland. I was MSP [member of the Scottish parliament] for half, but for two years I was still the MP for Shetland, so that required, you know, going up to Shetland doing surgeries, meeting public bodies, people… it worked.

PR: Was there anything unexpected about the experience?

JW: The reason why I find that a difficult question to answer is that I don’t know if I really knew what to expect. I did read Gerald Kaufman’s book [How to be a Minister, 1980], which I found very good. I think I read it probably after I’d been in office for a short while, and I could see what he was saying. I mean it is, it’s the same in Westminster, it’s a tremendously paper-driven system. Everything’s on paper and I still get the sense… there are some occasions when officials, as I say, I encountered it more as a deputy first minister rather than departmental minister, my departmental officials were pretty good at implementing things I wanted. There were one or two in other departments that I’ve tried who would just prevaricate or find ninety-nine reasons why it couldn’t be done.

PR: Can we just then leap on to 2010. When you became a minister then, how different was the experience?

JW: Probably not greatly different because things were very much alike. I mean the biggest difference was being a law officer, because it was a different dimension, dealing with teams of lawyers, which I hadn’t… Lawyers weren’t the officials I’d had at justice department, but you know there was that difference of the work I was doing as a law officer, but it was the same manner of working. The other thing is it’s true; you’ve got to be very careful, they will drive your diary if you don’t work out where you are. I mean I used to really resent back-to-back meetings, you never got a chance to draw your breath, and it happened more often when I was in Scotland than it did down here, especially if I was just taking a bill through Lords. They’d tie you up in meetings with bill team officials before you knew where you were.

PR: Did you think the civil servants understood parliamentary responsibilities?

JW: They certainly did when I was in the Scottish government. I think where they maybe didn’t initially in my role as Advocate General was I had probably a bigger parliamentary profile, involvement and activity than my two predecessors. I said to Nick [Clegg] when he appointed me, I said, ‘I don’t mind helping out with some of the constitutional stuff going through the Lords’, I was doing that parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Bill, then we lost the referendum. All the late nights and early mornings that they spent on that! But no, actually when they woke up to that, I was given – I think my previous predecessors had not had a full-time private secretary – it was a sort of a private secretary cum-PA and the legal secretary was the principal legal adviser here on UK government opinions and that, he did some of that work too. But they recognised pretty early on that I actually had a wider role than my predecessors, and they responded to it pretty well, and actually, latterly, in the first or second year, they actually rather liked it. It gave them something as well as just serving a law officer, you know.

PR: You were different, with your background experience and the coalition as well.

JW: But the civil service responded to that. They recognised that I was doing something a bit different and I had excellent support.

Jen Gold (JG): In terms of the day-to-day reality of being advocate-general, how was most of your time actually spent?

JW: Nothing’s ever typical. Suddenly you could find there was some urgent legal opinion that was required the day before yesterday and therefore you had to focus on doing that. For me, no matter whatever else I did, my core job was as a law officer, and if there was an urgent opinion which the attorney [general] and I had to do, that took precedence. I mean I was probably at my desk most mornings before 8am and probably not away until after 8 or 9pm. And again I had an Edinburgh office so I used to try and spend at least one day a week [there], usually on a Friday having got back on a Thursday night and going to the Edinburgh office on Friday before going back to Orkney on the last plane.

What I probably didn’t do as much of as my predecessors, was I only twice appeared at court. I appeared in the Supreme Court in the Imperial Tobacco case [Imperial Tobacco Limited v The Lord Advocate (Scotland)] and I represented HMG [Her Majesty’s Government] at the European Court of Justice on the Kadi case [relating to whether United Nations Security Council resolutions should enjoy primacy over EU law], but most of my legal work took precedence. I guess I was also part of the Scotland Office team, so that was quite a heavy load in the last parliament given all that was going on with the referendum. There was a Scotland Bill when I started and then all the referendum stuff, and there’s a lot of legal work involved in that too. You’ve got to make sure all these documents we put out in terms of the Scotland analysis… I mean we had to make sure they were legally fit and make sure there weren’t any howlers.

But I’d say no day was typical. You’d tend to be in Dover House [home of the Scotland Office] in the morning and [work in] the law officers’ corridor in the afternoon. I’d tend not to go into [oral] questions unless there was something interesting or I was answering a question or it was one of the bills I was doing. But I would at some stage in the day be in the House [of Lords].

JG: When you first moved into the role, did you have a sense of priorities and what you wanted to achieve?

JW: Yeah, some of it was reactive; you’ve just got to take what comes up. If a government department wants the Law Officer’s advice on something, you’d do it. There were one or two things I was quite keen on doing. One bit the dust in the Scotland Bill. I wanted to – at the moment, after Scottish parliament passes a bill the advocate-general or lord advocate or attorney can refer the bill to the Supreme Court if they think it’s beyond competence, and I wanted to try and change that, so you didn’t have to refer the whole bill, if you thought three clauses were… you could just do it. And actually we did quite lot of work on that but when we managed to have the final agreement with the Scottish government to get the bill through, that bit the dust, which I think was unfortunate because you hold up a whole bill over maybe two clauses. Maybe that was why it fell, I don’t know.

But the other thing was that I wanted to make sure that the UK government and government departments based in London remembered that they often had Scottish responsibilities; although they would say ‘This is a reserved matter’. Yeah, but ‘reserved’ covers Scotland, and there could be Scottish legal issues arising out of that. It may be reserved but actually as far as it affects Scotland, it’s Scots law. And when we were promoting legal services, I remember there was in fact three jurisdictions in the United Kingdom, and there was the Faculty of Advocates as well as the Bar Council, and there was the Law Society of Scotland as well as the Law Society. It was constantly nagging, but we made some progress. The last plan for growth for justice services did actually get proper recognition in Scotland and there was work I was doing towards the end trying to make sure if it was UK government work in Scotland, Scots law would be the choice of law. So I did see that as something I wanted to do to make sure, because we weren’t surprised that once or twice that there were blind spots, and we used to, as an office, we would do an annual promotion of the office to all the Whitehall departments, just to remind them.

JG: And you mentioned that obviously quite a bit of your work was reactive, and I wondered if you could talk us through an occasion where you had to deal with an unexpected event and how you went about doing that?

JW: Well I can’t because if it was a law issue then I can’t tell you what it was but let me give you a generalisation. If an issue suddenly came up, it usually was the case that the jungle drums had been beating beforehand, and my senior officials were aware that there was something in the offing, and probably my legal secretary had been talking to the attorney [general]’s legal secretary and they’d been getting some response from the requesting department. So at senior lawyer official level they would put their heads together and work out a brief, and draft an opinion which would then be submitted to the Attorney and myself. That’s very simple and you just have to apply your mind to it, sit down and grapple with it, probably have meetings, and if it was particularly problematic or particularly sensitive, it may well be the Attorney and I would meet. I have to say that in five years, I don’t recall any occasion when we ever had anything you’d call a major disagreement, or even that much of a minor disagreement, either with Dominic [Grieve] and latterly Jeremy [Wright] [the former and current attorney generals]. I would just say that’s how the coalition worked.

PR: Can I come onto that, because you are – the word ‘unique’ is over-used – but you are in the unique position of having served in two coalitions. What lessons can you share about how to work in coalition and how to make government work in it?

JW: Yeah, one of the important things was that Nick [Clegg] was fully involved, and that caused quite a lot of work in terms of getting his office structured. It was the same for me really; if you were going to take responsibility for things, you actually had to have sight of it, and you had to have an opportunity to intervene. I took the view that should primarily be done at departmental level; there weren’t many departments we didn’t have ministers in and I don’t think it worked quite as well as we’d want it to sometimes, it varied from department to department and usually personality’s more important than anything else.

But my view was if you were the minister of state, with a Conservative secretary of state, and you’re Lib Dem minister of state at department X, then you were the Lib Dem minister for that department. I know they allocate responsibilities within the department, but you were also the Lib Dem minister that should be looking at other things in that department that weren’t necessarily your primary responsibility. So that if there’s coalition issues, if there’s a problem, you anticipated something, you could flag it up. I’m not sure that worked quite as well as it might have done; I don’t think Conservative secretaries of state always necessarily recognised that our… but there were always exceptions to that. Some were astoundingly good, but others, I must say, weren’t bad, they just never thought about it.

It was important that Nick was ultimately the last word and that if there was a problem [he could] take it to the prime minister. I didn’t anticipate the Quad and in fact the initial stuff that Oliver Letwin [then minister for government policy] and I looked at on the day after the new coalition agreement was signed, we did anticipate more of a coalition committee through which things would go up after all other attempts at resolution. It didn’t happen and of course the quad evolved. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing actually, because it did mean if the quad made a decision that went quickly through Whitehall and everyone knew, there was no comeback, or only very rarely any comeback.

I did think, and I think I did something for you [Institute for Government] about the first anniversary [of the coalition] on special advisers, and we were a bit slow off the mark. Special advisers… lots of things are said about them! One of the things they do is to ‘oil the wheels’ and the other thing is to make sure that – again, I would have said that it always happened – but I would, only in Scotland agree something with the Labour first minister if I thought I could deliver it with my troops. It used to frustrate the Labour MSPs quite a lot, because clearly our MSPs knew a hell of a lot more about what was happening; I had to talk to them. There was no point signing up to something at the cabinet, and then going back to the [Liberal Democrat] group and finding out it was completely un-sellable.

PR: How different was operating in coalition in Edinburgh and London?

JW: Size. I mean, the Scottish government was pretty compact. I think in many respects the government in Scotland, putting aside the present government, governance in Scotland was in many respects easier; not that decisions are any easier, but the lines of communication are so much shorter. You didn’t have to do write-rounds, that’s an exaggeration, but you know, you could get things done, agreed far more quickly. You didn’t have to go through the other team’s processes, or a write-round is the word.

Also engagement – I hate the word ‘stakeholders’ but it’s as good a word as any. Lines of communication were shorter. I mean I think if you looked, and you may have done that at the time of the foot-and-mouth outbreak, I think we were far more successful in the Scottish government in handling that than the then UK government was. But one of the reasons was that the then UK government had to deal with the NFU [National Farmers Union] which wasn’t necessarily sure about the recovery of… Whereas in Scotland it was a very close-knit [community]. Sometimes there’s a problem with people knowing each other too well but it was easy to sort things out and I think that was the biggest difference, its size.

[Also in Westminster] just the amount of bureaucracy to track a decision… The classic example is you’re in the Lords, you’re dealing with a bill, someone puts up an amendment from the backbenches that you think is eminently sensible, and the hoops you’ve got to go through to be able to be able to get clearance to say you’ll accept it. Technically actually you could have just stood up and said, ‘I’m accepting it’ that’d be a minister saying it at their dispatch box and you’re landed with it but there’d be all hell to pay. Even the simplest things are a real frustration. There’s others that would cause frustration too, in terms of your handling of the Lords, because the opposition or very often your own backbenchers or Conservative backbenchers, couldn’t understand why you couldn’t just say [you’d accept the amendment] there and then. Maybe I was too lax with it. But you had to go back and get the clearance.

PR: Looking at both periods, what would you regard as your biggest achievement in office and how did you achieve it?

JW: Oh, hell…. There’s a lot of things in Scotland. PR [proportional representation] for local government in Scotland was quite a major breakthrough, and I achieved it through taking it as far as I could with Labour in the first course, because we were never going to quite swallow it but we got things moved by enquiries and so when it came to the 2003 agreement, the Coalition Agreement, it was there and I was fortunate in having a first minister, Jack [McConnell], who actually supported the policy too. But that was transformational too in terms of changing the whole system.

PR: What you’re hinting there Jim is that the crucial thing was to build up wider constituency support first.

JW: Yeah. Well we were never going to get it overnight. The Labour Party conceded a hell of lot on that. I’m told sometimes to get the blame for some of their present misfortunes – that I whittled away their local government base. I mean I know that’s not the case, but it changed Scottish [politics]. I mean local authorities are far more responsive to their local communities. I suspect it is probably the biggest political change that we made.

PR: It’s a pretty big one! In terms of decision-making structure, how much does the collective decision-making process come into it?

JW: Ultimately in that case, the negotiation of that Coalition Agreement in 2003, it was very collegiate in terms of both sides met, and by the end of the day there were about five issues that came up to Jack and I to sort out between us. But again, we were not taking that decision in a vacuum, you know. There was a lot of work in going to the point where this was the final decision and it’s basically only you two that can come to that agreement.

JG: And what you do feel was your biggest achievement in the last government?

JW: I would like to think that we did succeed in… I think it’s like painting the Forth bridge, once you finish you’ve got to start again…

PR: World Heritage Bridge!

JW: World Heritage Bridge, indeed! You know, it’s still a Whitehall fact that Scotland did have responsibilities; it was a mixed success but there was work there that was quite important to do that. I mean there were bits of legislation – Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act, I was heavily involved in that. Tina Stowell [then Leader of the House of Lords] led it. The Fixed-term Parliaments Act – we’ll see if that stands the test of time, I rather suspect it will actually.

PR: No signs that the Tories have any desire to amend.

JW: No. There’s a review at the end of this parliament.

PR: Yeah, the end of this parliament, after 2020.

JW: Well I said it was nonsense doing it at the end of the first parliament because it only came into effect halfway through. As a Law Officer you don’t have great achievements in that sense. I like to think we got our advice right to government.

PR: Looking at both your experiences, what was the most frustrating thing about being a minister?

JW: Again this might be a personal criticism of myself, but not getting the diary right, the balance right, at times. You don’t really get much time to step back and reflect, which I suspect was more important in the law offices than in Scotland. You did need that time and it wasn’t always there.

PR: And how do you think that ministers could be made more effective, and government more effective? What were your reflections on that? So you had, at the very beginning, you had a number of jobs when you were deputy first minister, departmental jobs, then you had the law officer job, much broader job here. When you look round on what you yourself judge to be effective, what were the keys to it?

JW: There’s no substitute for being at the top of your brief. You know, preparation, particularly in the House, and having the infrastructure in place in your office, particularly the support to make sure you can be on top of your brief. So I think preparation is very important. Frustrations… well I told you frustrations, the diary. How to make it more effective? I think if we could simplify some of the decision-making.

PR: You mean the write-rounds and things like that?

JW: I don’t know if that is possible, because I mean the theory behind that is that is how you apply collective responsibility, so it’s not a daft thing, but it does tend to make the system a bit cumbersome.

PR: What advice would you give to a new minister?

JW: Keep control of your diary, keep on top of things. If you’re appearing in the House, the Commons or Lords, or Scottish parliament, be well prepared; you know, have a response. I do think the role of parliament of holding the executive to account is fundamental, but if you’re going to be held to account you’ve got to be ready to be held to account, you know.

PR: Both in Holyrood and here – and of course it’s very different here because of the Lords – did you feel you spent enough time in both places gathering support and listening to opinion?

JW: Probably not here, although, no, that’s not true actually. I didn’t hang around the bars or the tearooms trying to gather support and listen to opinion, but when we were having difficulties, probably even more so here we would actually invite Lords in, sit down and talk to them. And not just from my own party; I mean obviously there’s a particular [dynamic] because of the coalition, not least with my own party to get them on side. But yeah, the parliamentary Voting Systems Bill, I spent a lot of time with the crossbenchers trying to understand where they were coming from on different things. So when I think about it, we did actually have quite a bit of engagement. And then in Scotland, I think I was probably round parliament more… it feels like that! Whether it was the case or not, I don’t know. But then in the Scottish parliament, I was the party leader, and therefore it was important that I was doing that stuff.

JG: And you mentioned frustration that you didn’t feel you got your diary right. But in hindsight is there anything else you would highlight in terms of how you would approach the role differently?

JW: I’m sure there is… I would hate to give the impression that I did it perfectly or anything, far from it! I’m just trying to think what would be… something will probably be blindingly obvious that I’m missing, but if I think about it, it’s really all a feature of time, the diary or whatever it is. You could be run ragged by the end of the day. The fact is it’s one of the reasons I gave up and retired in Scotland. When every Sunday afternoon was being taken, as well as all the other times, and also I’d done it long enough. Yeah, I think it is just this constant… pressure’s not quite the right word, there is a pressure there, but I don’t think you necessarily perform at your best when you’re under that. It’s flitting from one thing to the next.

The other thing I would say, and it’s up to others to judge whether I succeeded or not, but I always had great store in treating officials courteously and in a personal way. I think you get far more out of them than [by being] demanding. I think that’s good advice to ministers, I would say, treat your – particularly your private office but also, generally, the officials – well. They are people!

- Topic

- Ministers Devolution

- Keywords

- Coalition government Law Criminal justice Cabinet

- United Kingdom

- Scotland

- Political party

- Liberal Democrat

- Administration

- Cameron-Clegg coalition government

- Devolved administration

- Scottish government

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Legislature

- Scottish parliament House of Lords

- Publisher

- Institute for Government