Rishi Sunak's reshuffle – February 2023

The PM has restructured several departments, and appointed new ministers to head them. The IfG reshuffle team tracked all the changes on the day.

The prime minister has restructured several departments, and appointed new ministers to head them. The IfG reshuffle team tracked all the changes on the day

Big changes to government

18:17

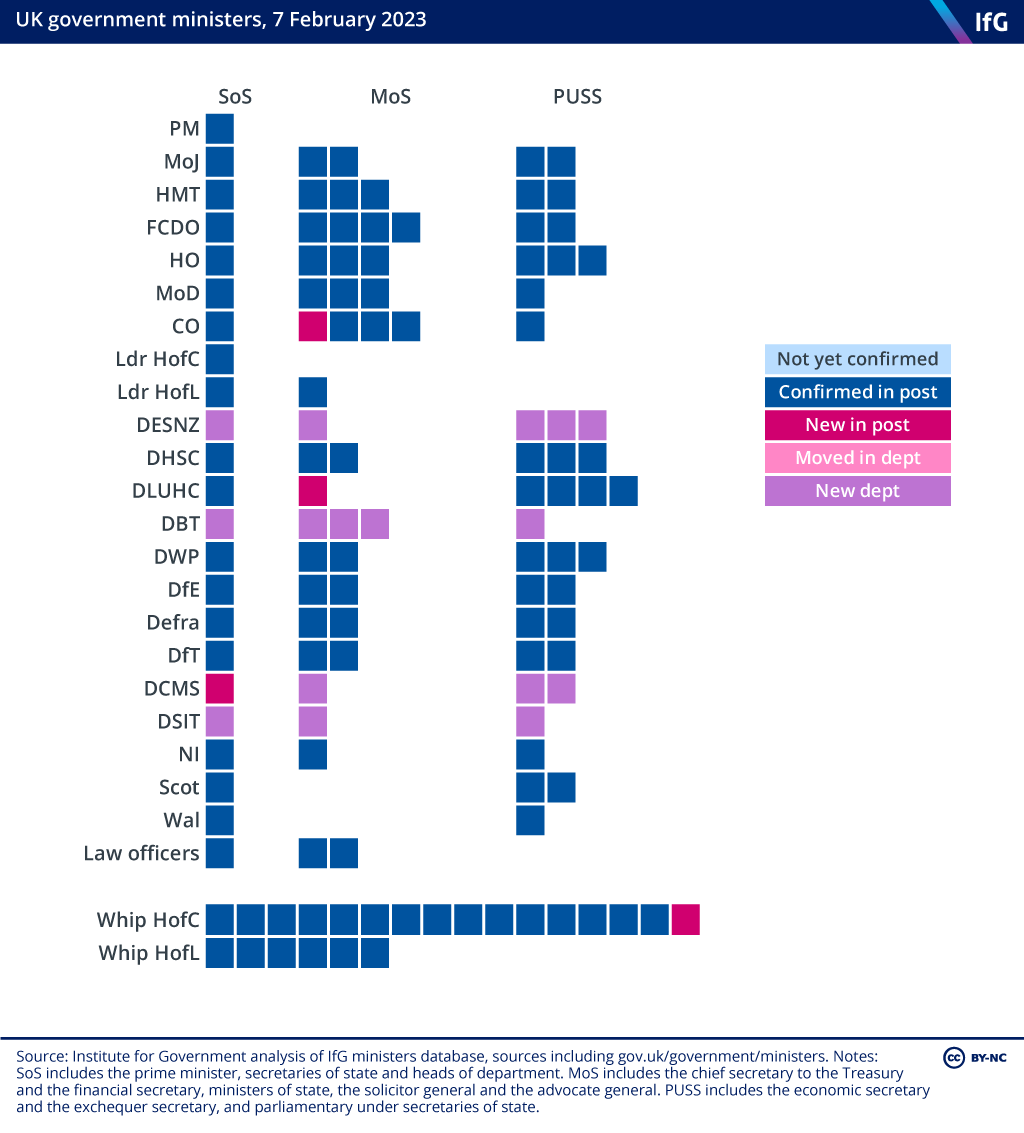

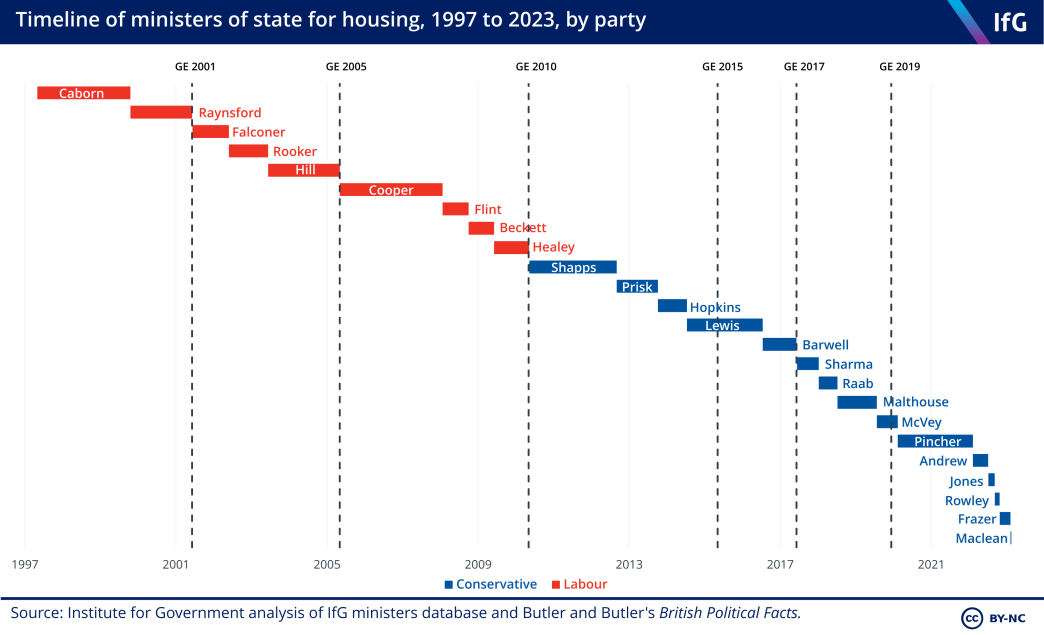

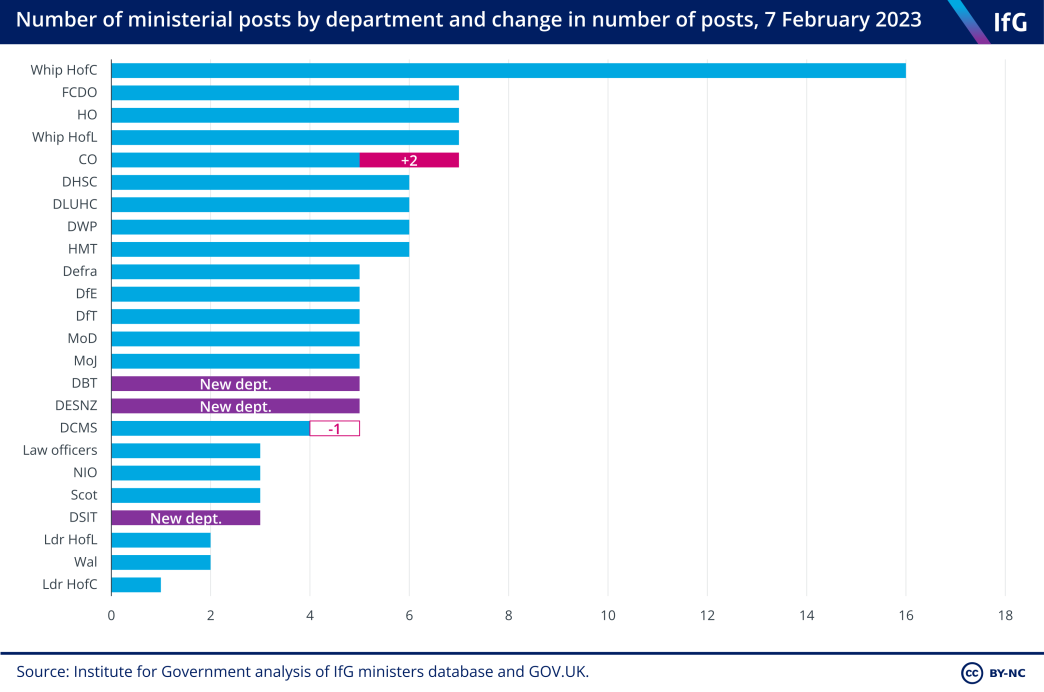

So, we now have all the changes to government announced, with the junior ministerial roles in the four new departments filled. Most of the ministers simply moved with their portfolios, though Rachel Maclean returned to government to join DLUHC, possibly to fill the housing minister vacancy created by Lucy Frazer’s promotion. If that is the role she is taking, that means Maclean is the fifth housing minister in the last 12 months, and the 15th since the 2010 election. The only person who has never been in government before is Ruth Edwards, who is a whip.

We have also seen a change in the number of ministers at some departments, with the Cabinet Office gaining two (including Greg Hands as party chair and minister without portfolio). DCMS has lost one department and DSIT has the smallest ministerial team of the new departments.

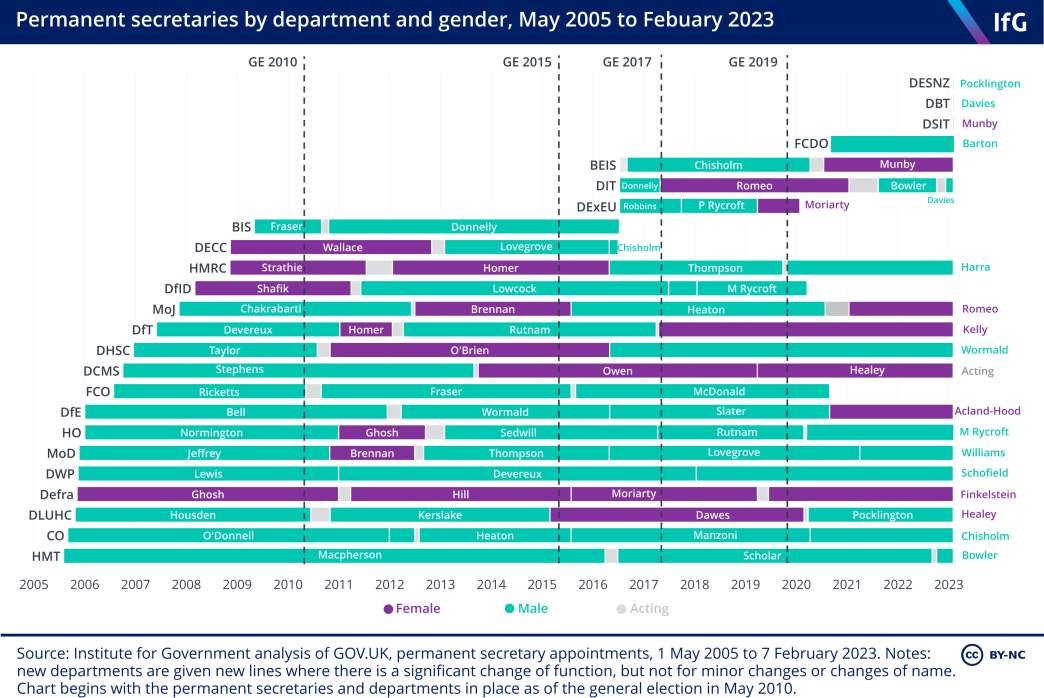

This reshuffle has not just been limited to ministers. A number of departmental permanent secretaries – the most senior officials in each department – have also moved role.

Those moving include Jeremy Pocklington, permanent secretary for the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, who has moved to head up the new energy department, and Sarah Healey, permanent secretary at the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, who has replaced him at the levelling up ministry.

Some of these changes reflect the experience of the officials involved. Pocklington had worked at BEIS, and its predecessor the Department for Energy and Climate Change, before moving to DLUHC, so has a background in energy policy which will be useful in his new role. However, these moves continue a high level of churn amongst senior officials. Out of the 18 permanent secretaries who led their departments into the last general election, just five remain in the same post.

DIT ain’t over til it’s over

15:37

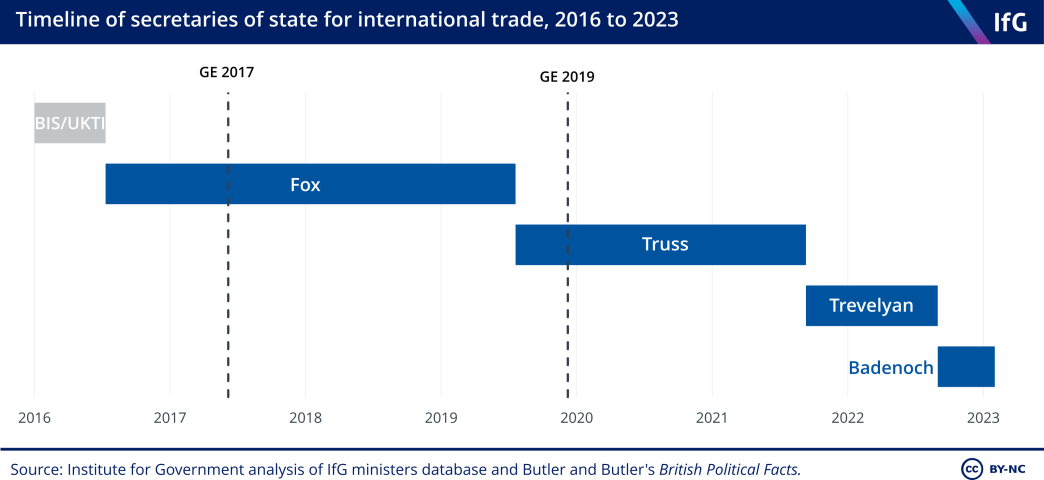

The Department for International Trade was created by Theresa May in 2016 as part of her determination to show that she was committed to Brexit. It is no more, with the department merging with the business parts of BEIS. The department only had four secretaries of state (and is probably the only department in government ever to have had more women as secretary of state than men). The second longest-serving secretary of state for international trade was of course the shortest-serving prime minister ever, Liz Truss.

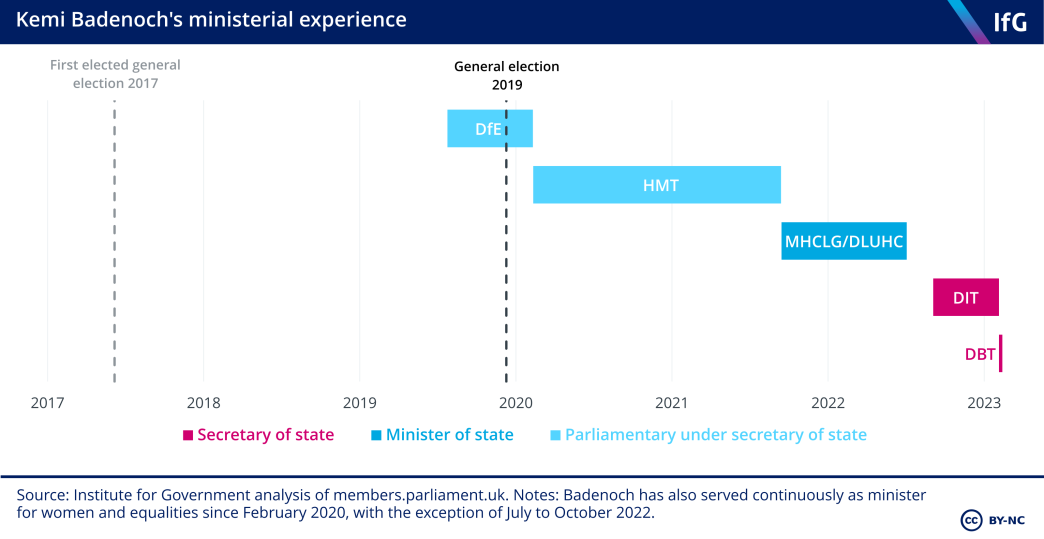

Kemi Badenoch takes her trade portfolio with her to the new, bigger Department for Business and Trade. It is her second cabinet post.

In BEIS gone by

15:07

Today’s decisions by the prime minister mean that the remaining two departments created by Theresa May – Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and International Trade – are no more.

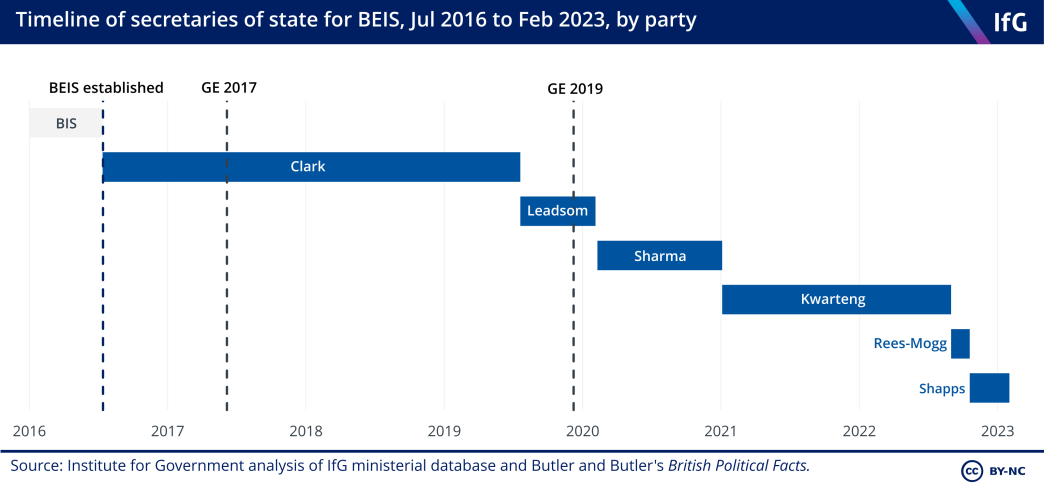

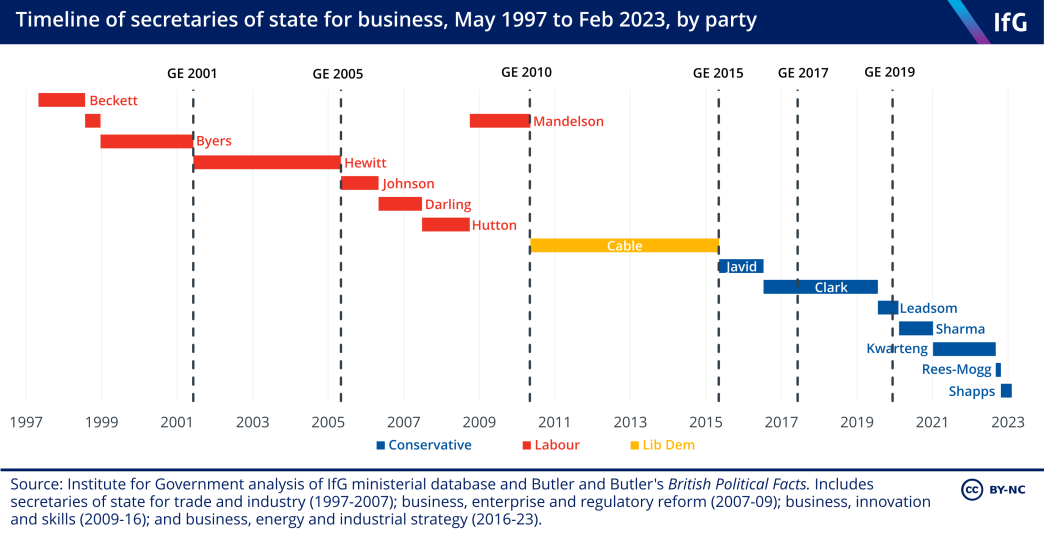

BEIS had six secretaries of state in total, with Greg Clark overseeing the department for almost half its existence.

Greg Clark talked to the Institute’s Ministers Reflect series about the creation of the department in 2016 – his experience of encountering one department that still felt like two is probably something some of his successors are dealing with today:

"It felt like two organisations – we literally had the 1 Victoria Street headquarters which I was obviously familiar with from when I was there as the universities and science minister. We had the energy and climate change department which was in Whitehall Place. They were physically two departments, not even neighbouring departments. Very different cultures between them: the energy and climate change department was very much the mission-orientated department, we’d had the Paris summit [on global climate targets] not long before – a great success for the department and they did a brilliant job out there."

"The business department was obviously a much longer standing department, also I’d been a special adviser at what was then the DTI [Department of Trade and Industry, a predecessor to BIS/BEIS], right at the beginning of my time in politics. So the first thing was that, in effect, I was secretary of state for two departments, that had become nominally one."

Greg Hands’ first cabinet job

15:02

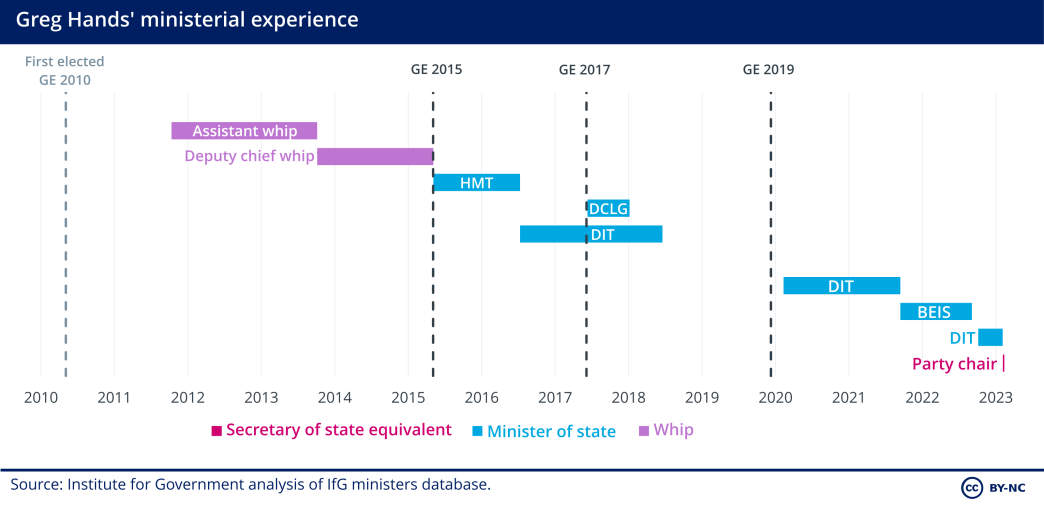

Greg Hands has replaced Nadhim Zahawi as party chairman, leading the party campaign machine – the next bit test for which will be the May local elections.

Hands has been in government since 2011, with most of his experience in trade-related jobs. The party chairman role is his first cabinet role, but is of course a party role, not a government one (he is still a member of the cabinet, but is paid by the party, not the government). Hands is one of a few inner London Conservative MPs.

Wholesale departmental change

13:58

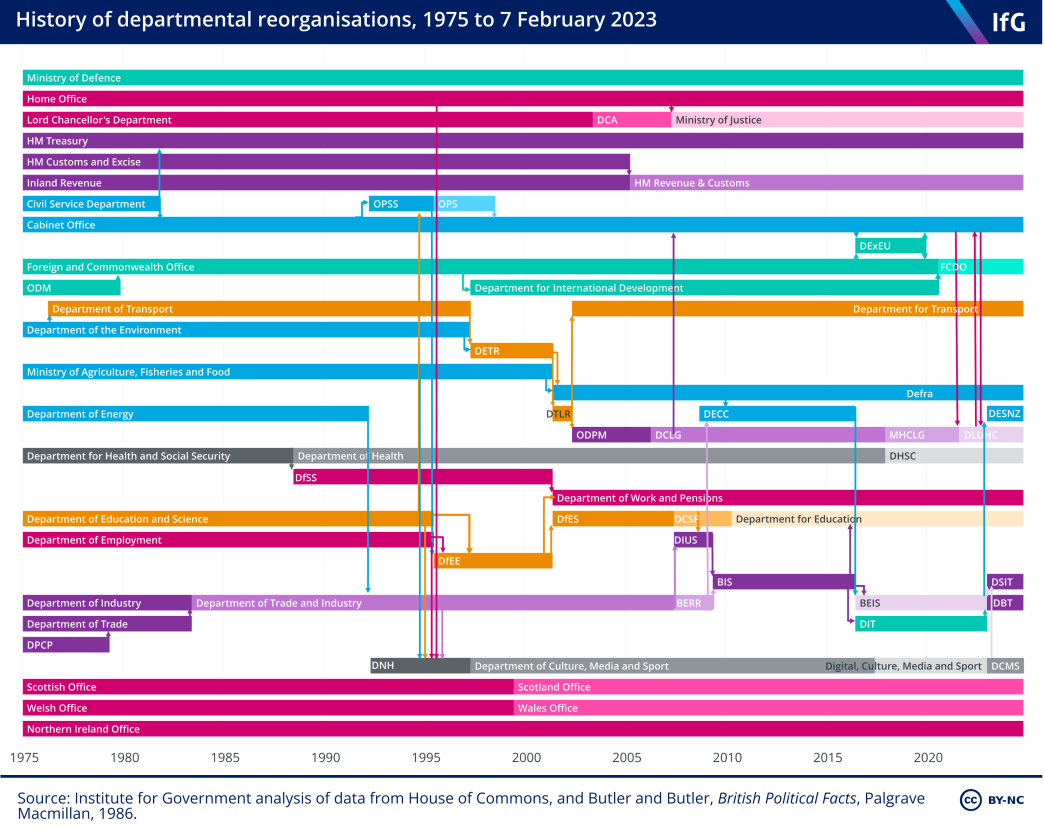

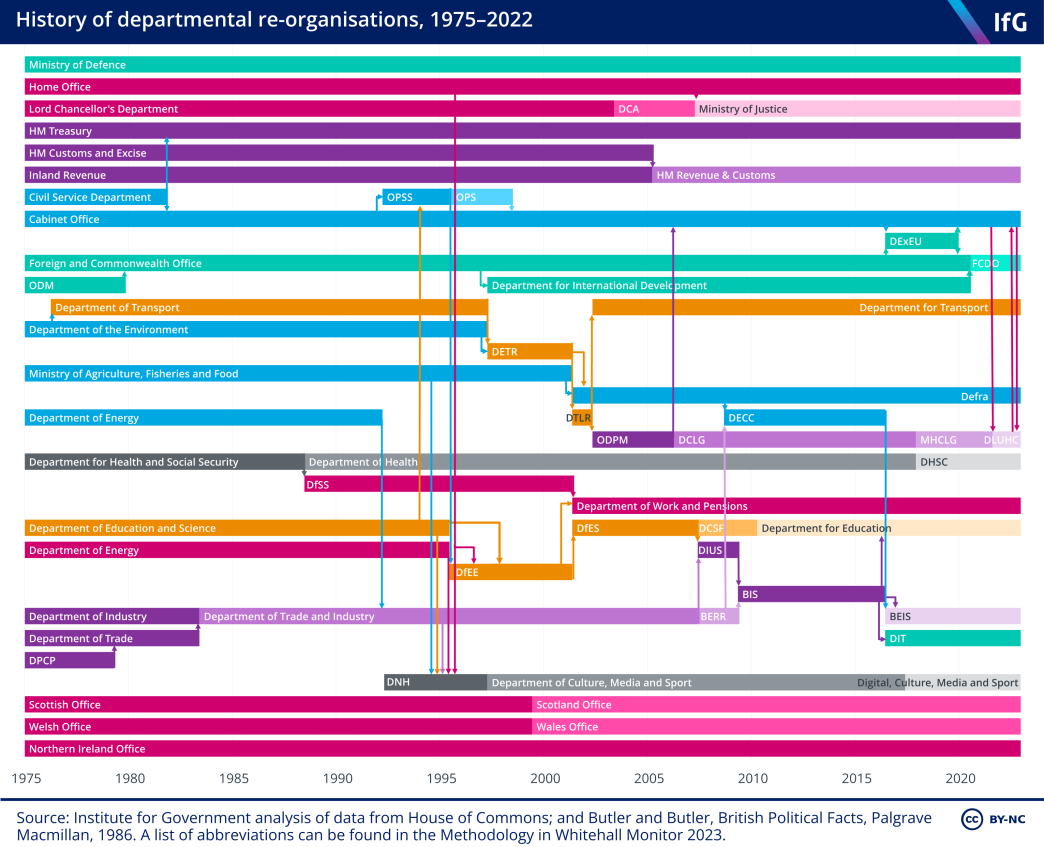

Today’s announcement represents the biggest change to the landscape of Whitehall since at least 2007, with three new departments coming into existence on one day. Here you can see the frequent reorganisations that UK departments go through:

IfG senior fellow Giles Wilkes set out his views on what the reorganisation today signals about the recent history of Whitehall departments:

The government has admitted that its attempt to get the energy side and business/industrial side to work together has failed. That is a pity. The most straightforward justification for an industrial strategy approach to business is found in the enormous investments needed for reaching net zero, an investment agenda that needs clear, consistent and committed signals to business over a long period of time. The department in charge of that needs to have clout and business nous to stand up to the Treasury, bring energy users and producers onside, and understand how investment really works. One risk now is that the departments run by Michelle Donelan, Grant Shapps and Kemi Badenoch are now at loggerheads rather than working together. Another is that none on their own have the clout to stand up to the Treasury which has in the past been a force for short-termism when it comes to creating a long-term framework for investment.

The creation of department specifically for science, innovation and technology may send an encouraging signal to the science community looking for a powerful champion in government and reassurance that the uplift in R&D spending will be protected in future austerity. Whether it makes the system as a whole easier to control and direct at the governments' priorities is less clear. Science spending is decided in a very decentralised way through many different arm's length organisations, competitively. Making it do anything differently is hard work, no matter what the Whitehall structure.

Digital and culture split

13:04

The creation of the new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (headed by Michelle Donelan) means that the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (headed by the newly promoted Lucy Frazer) is a smaller organisation than it used to be. With rumours of permanent secretary moves too, the departments will be facing a lot of uncertainty over the coming weeks. IfG associate Gavin Freeguard expanded on his list of questions for the arrangements between the new departments:

- Is the undoubted disruption – of merging and moving teams and systems from existing departments – worth it, at a time when there’s a lot of digital policy making to be done? As well as the Online Safety Bill, there’s the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill – already in legislative limbo after changes of prime minister – and a promised Digital Markets Bill.

- What influence will the new department actually be able to have across government? The digital world and the physical world are now intertwined: any government policy and any government service has to reckon with ‘digital’. DCMS has never completely shaken off its perception as the ‘ministry of fun’ (never accurate, given the economic and cultural value of its other domains), even as its digital and data responsibilities grew, and has always lacked the levers of the centre of government to get others to do things. Why should a brand new department be different? Do we need to think more radically about how to embed digital/data policy capability and literacy across government? And how will the remaining DCMS manage its relationships with the rest of government?

- What is government’s vision for digital and data policy? Beyond words about innovation and growth, it’s not entirely obvious, and this breeds inconsistencies: for example, the Online Safety Bill believes regulation is good and can protect people, while the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill believes regulation is bad and wants to weaken existing protections. Building a new department will not fill the gap where policy and politics should be.

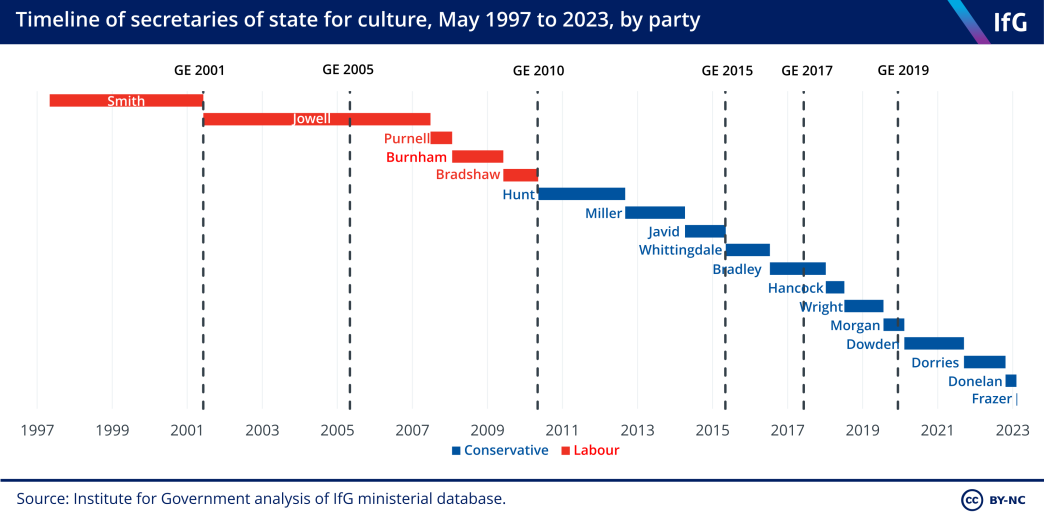

DCMS, in its various guises, has seen huge amounts of ministerial turnover, with 12 secretaries of state since the 2010 election:

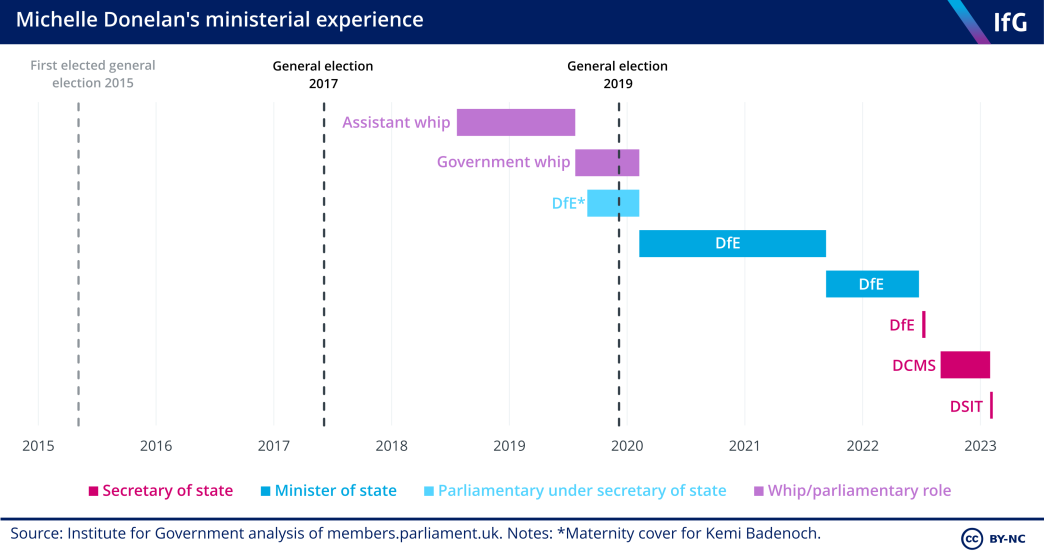

The two secretaries of state have also moved around a lot, with Donelan taking on her third cabinet-level role:

Donelan will be going on maternity leave later in the year, so there will be another minister in post temporarily.

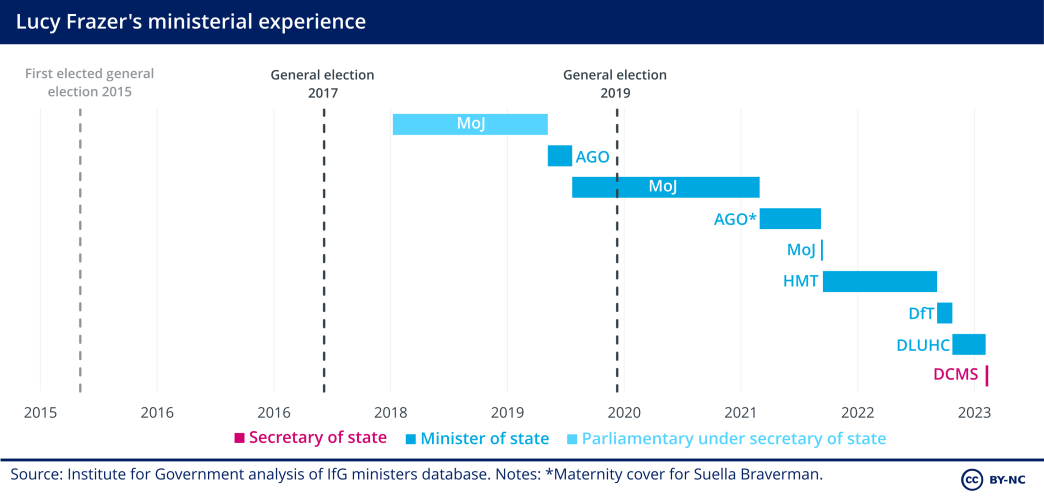

And Lucy Frazer, who has worked in five departments, but not yet in DCMS, is taking on her first secretary of state role:

Making a success of the energy department

12:27

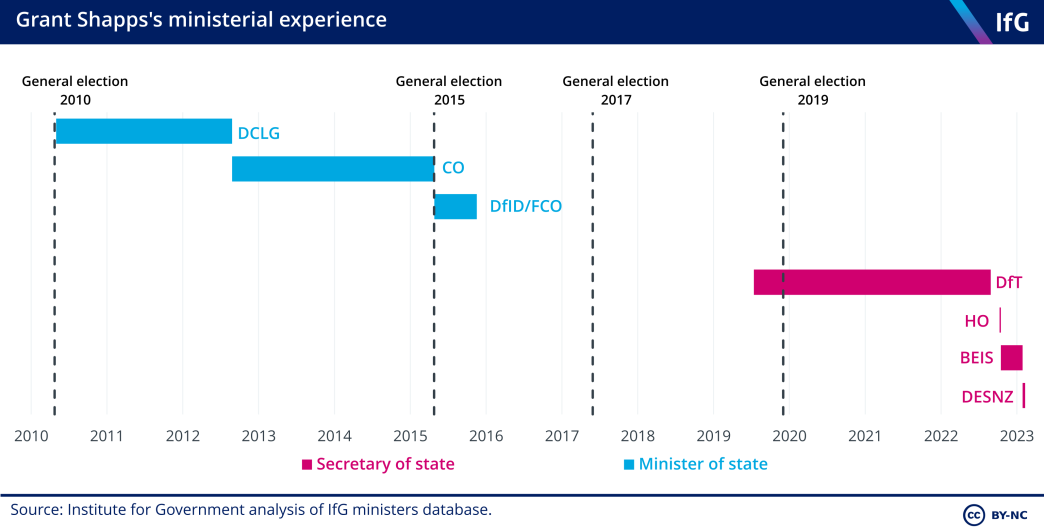

Grant Shapps is now secretary of state for energy security and net zero, a big role that is particularly important at the moment given the cost of living crisis and the climate crisis. IfG associate director Tom Sasse has set out his thoughts on what the new department means:

“The creation of a department for energy and net zero will divide opinion. Some see giving a cabinet minister a tighter focus on energy security and the net zero transition as a major plus, compared to a BEIS secretary who can get distracted by whatever business or industry needs help. Many officials from BEIS’s predecessor, the department for energy and climate change (DECC), remember the department fondly. But others argue that a slimmed-down department will lack clout in Whitehall – and struggle to influence others, which is particularly important for a long-term cross-cutting goal like net zero. The fact that the three tasks the prime minister has given the new department include ‘halving inflation’ but not ‘reducing emissions’ also raise questions about how much the Sunak government will really prioritise the latter. Less than two years out from an election, there is also a risk that the change doesn’t last – and the cost in terms of disruption outweighs any benefit.”

This is Shapps’ fourth cabinet post (he was home secretary for six days, between Suella Braverman’s dismissal and her return to government).

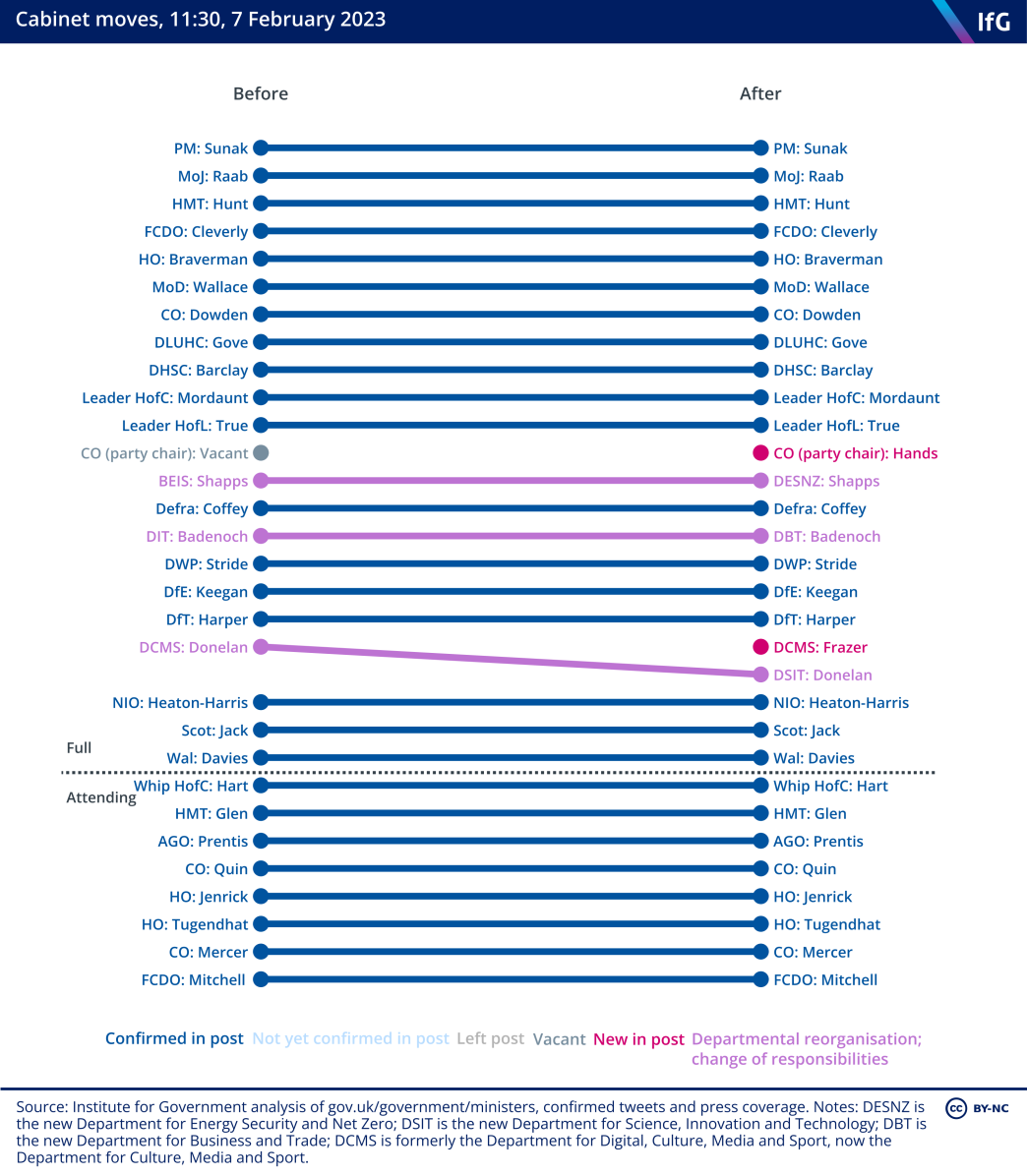

Cabinet moves confirmed

11:35

Well, after a few hours of speculation, we have confirmation of the changes to the structure of government and cabinet.

Kemi Badenoch, former trade secretary, is now head of the Department for Business and Trade – a big expansion of her role. The Department of Trade and Industry existed until 2007, but of course during that period the UK was a member of the EU, so had less domestic responsibility for trade policy. Sunak is presumably hoping that bringing together business and trade in one department will allow the government to get better intelligence on what businesses need from trade policy and create the conditions for better growth.

Grant Shapps now heads up the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, a section of his previous department. The fact that net zero is included in the title harks back to the previous Department of Energy and Climate Change, which Theresa May abolished in order to establish the Department for Exiting the EU.

Michelle Donelan, formerly secretary of state at DCMS, is now in charge of the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, which brings together bits of BEIS and DCMS. IfG associate Gavin Freeguard writes that questions remain about how this department will work:

“What will actually move from DCMS to a mooted Department for Science, Innovation and Technology? Some reports suggest the Online Safety Bill – in many ways, government’s flagship digital policy – could remain with DCMS. How easily can we distinguish media policy – massively impacted by the digital revolution – from other digital and data considerations? Not thinking this through will only store up future problems for cross-government working. Will some issues receive less prominence in a new department, and how will a ‘science, innovation and technology’ lens change how they are regarded?”

And Lucy Frazer moves into cabinet for the first time, as secretary of state at the reduced Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Frazer has been around government for a long time but this will be her first cabinet post – and whether or not the Online Safety Bill stays in the department, DCMS will be busy, with a sports and a gambling white paper due soon.

And Greg Hands, former trade minister, is now party chair, taking over from Nadhim Zahawi who was sacked for breaking the ministerial code. Hands’ first challenge will be preparing the party for the May elections.

Another business secretary?

10:41

If, as rumoured, the business parts of BEIS are merged with the trade department and Kemi Badenoch, current trade secretary, takes over the new organisation, she’ll be the sixth business secretary since the 2019 election. Just as the department has seen many changes over the years, the secretary of state position has changed hands regularly.

The ever-changing business department

10:16

The current Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy is rumoured to be facing a split, and merger with bits of other departments, to create a new Department for Energy, a Department for Business and Trade (merging with the Department for International Trade), and a Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (merging with bits of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport).

BEIS has a history of changes – the department and its predecessors have been through many restructures over the years.

What do we know about rearranging departments?

09:54

With reports that the prime minister is planning big changes to the structure of Whitehall, what do we know about how these changes work and the impact they have?

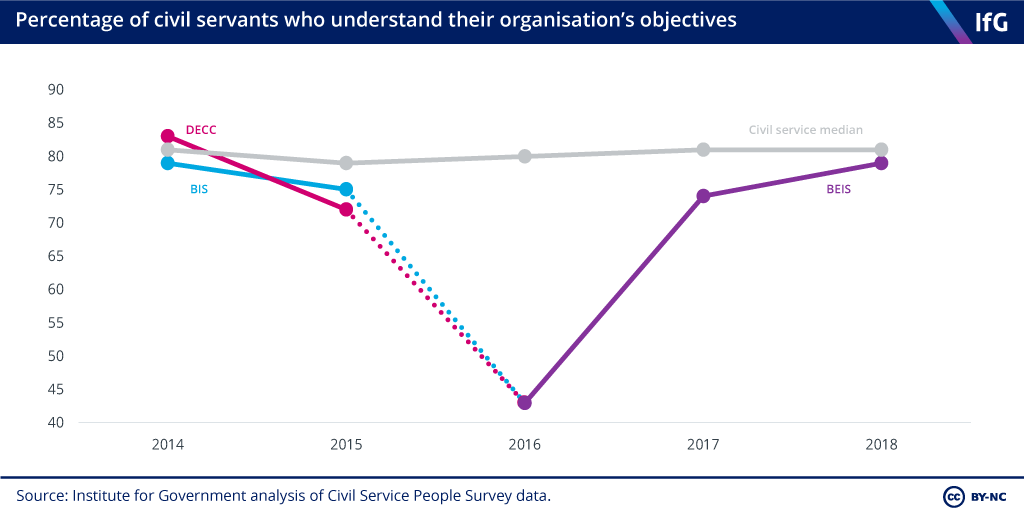

A few years ago the Institute looked into how to create and dismantle departments, and found that:

- The changes can cost upwards of £15m in the first year, with administrative costs and a hit to productivity as civil servants adjust to new structures.

- The practical changes – new HR and IT systems, questions about aligning pay scales for officials from the predecessor departments – can take at least two years to sort out.

- Morale often takes a hit, as people deal with the uncertainty of their new roles and working out what the department is trying to do.

Of course, none of this means that the prime minister shouldn’t rearrange departments – but he needs to be sure that the new structures will be better at delivering on his priorities, and that the disruption will be worth it.

Rishi Sunak reshuffles Whitehall

09:33

This is how the landscape of government has changed in recent years – the last big changes were the abolition of DExEU, in January 2020, and the merger of the Foreign Office and the Department for International Development, in September 2020.

With reports that the business, trade, and digital and culture departments are all slated for a restructure, this chart could look very different by the end of the day.

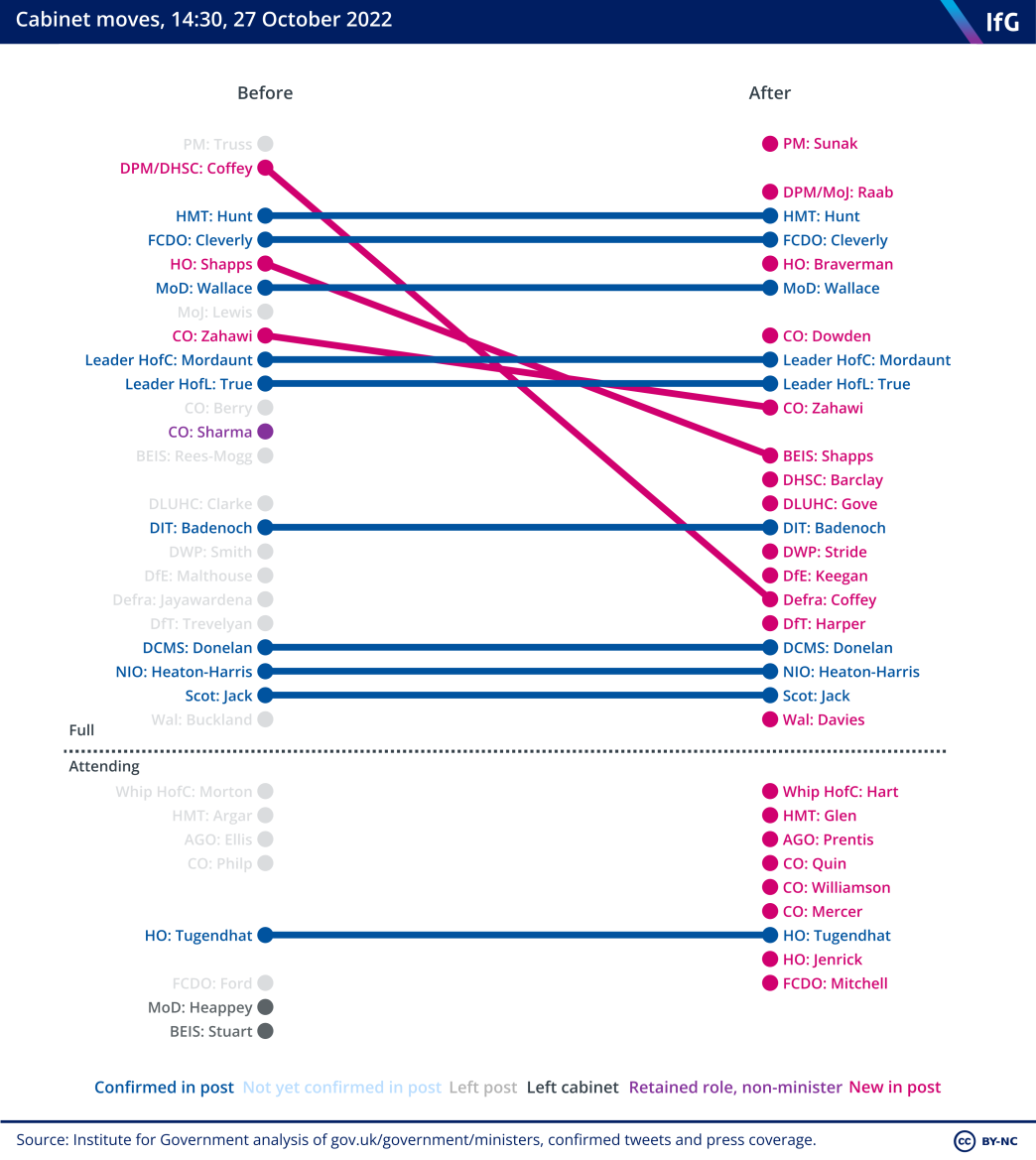

And who will head up the new departments? Rishi Sunak made lots of changes to the cabinet when he took office in October – how many of these people will be in the government later, and will there be any new names?

And the other key personnel question is who fills Nadhim Zahawi’s place as party chair? Follow here for all the latest throughout the day.

- Topic

- Ministers

- Position

- Prime minister

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Department for International Trade Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak Nadhim Zahawi Grant Shapps Michelle Donelan Kemi Badenoch

- Publisher

- Institute for Government