What is a spending review?

“Spending reviews” are a process by which government sets out detailed plans for public spending for government departments, typically several years ahead. Spending reviews tend to coincide with the UK’s more frequent annual budget process, at which point considerable work is undertaken with other departments to develop detailed (multi-year) spending plans.

Not all spending decisions take place at spending reviews. The Treasury will likely still make some spending announcements - on issues that need addressing relatively soon or are seen as political priorities - at ‘regular’ budgets. The 2023 budget, for example, announced a package of measures aimed at tackling labour market inequality, such as improved childcare. The government will also outline headline levels of public spending beyond the end of the spending review period, including the capital and resource split but not specific allocations to departments or spending areas. 19 This happens because the forecast that the government commissions from the OBR usually commissions to support budget decisions must be for the next 5 years, meaning that the Treasury must provide the OBR with its plans for the overall level of public spending for that period, which typically includes at least a couple of years that lie beyond the spending review period. These ‘pencilled in’ headline spending numbers are often criticised for appearing implausible – they are often revised up when a new spending review takes place, as in 2015 and 2019. This probably happens because pencilling in lower spending makes it easier for chancellors to appear as though they will meet their fiscal rules. See e.g., www.committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/2995/html/

Spending reviews will only plan the predictable elements of departments’ budgets: what is formally known as “Departmental Expenditure Limits”. This can include predictable day-to-day spending such as military staff and schools grants or capital projects like HS2 or housing. Annually Managed Expenditure (AME) is not set at spending reviews because it is too unpredictable to be subject to firm multi-year limits and includes functions that are demand-driven such as pensions or welfare payments.

Unlike budgets, spending reviews have no legal basis and are instead a ‘statement of intent’, which only attains real force when it is implemented through the annual ‘estimates’ process.

Why were spending reviews introduced in the UK?

For most of the post-war period up to the end of the century, UK fiscal policy was extremely ad hoc, with successive chancellors deciding on tax and spending policy in response to the economic challenges of the day. Often (as in 1949, 1967, 1969 and 1976) fiscal policy was determined by the demands of a sterling crisis, with the UK using a system of annual public expenditure surveys to set departmental budgets. This system was rightly criticized for encouraging short-term thinking and for being overly complex and time-consuming.

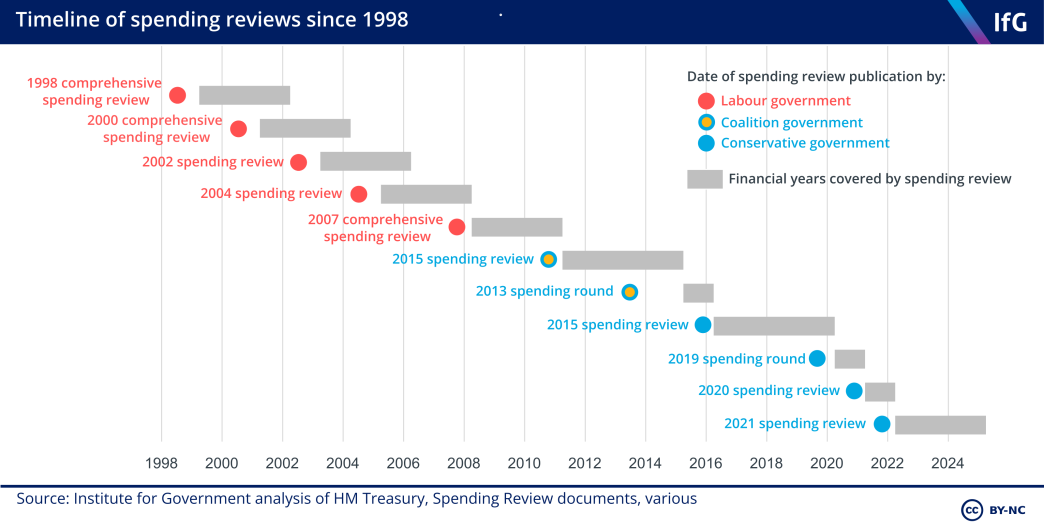

Spending reviews were then introduced in 1998 as part of a package of reforms to the UK macroeconomic framework introduced by New Labour. Setting out multi-year spending plans was thought to bring multiple benefits: providing greater certainty, encouraging longer-term planning, and allowing for greater flexibility, such as moving spending between years and allowing individual departments to plan strategically over the medium term. However, the initial ‘end-year flexibility’ arrangements that were first introduced were replaced with a more restrictive ‘budget exchange’ mechanism following the financial crisis. 20 www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/commons/Scrutiny/120125-Changes-in-financial-management.pdf

From the Treasury’s point of view, they provide increased stability to the public finances and enable it to consider competing pressures on the Exchequer in the round, at one moment in time.

This approach has generally been maintained by subsequent governments, although there have been some changes in response to specific circumstances. For example, during periods of economic uncertainty such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the government has sometimes chosen to conduct a one-year spending review instead of a multi-year review. This has only reduced flexibility further.

Spending reviews were also designed to link spending more closely with the government's strategic priorities and to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of public spending or ‘allocative efficiency’. Since their introduction governments have tried various approaches to achieve this aim. New Labour initially attempted to achieve this through ‘public service agreements’ (PSAs). Since then, Single Departmental Plans (SDPs) were also tried and then abandoned in favour of Outcome Delivery Plans (ODPs). See our report on performance management for more details. Over the past few decades the UK has led the way in expenditure management, with many countries adopting medium term expenditure frameworks (spending reviews) and performance management frameworks similar to those used here. 21 https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2016/12/31/United-Kingdom-Fiscal-Transparency-Evaluation-44395

How do spending reviews work in practice?

The Treasury is responsible for managing public spending. It delegates budgets to departments and sets rules for how leaders of public organisations should manage their money. During spending reviews, the Treasury’s spending teams 22 Of which there were 20 in 2018, according the the NAO. Each team is typically responsible for the spending of a (set of) department(s). www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Improving-governments-planning-and-spending-framework.pdf lead on the advice that goes to ministers on how money should be allocated between and within departments.

A spending review is a vast and complicated process: one that allocates trillions of pounds in taxpayer money (close to half of the UK’s income) across a huge range of government policy, making incredibly difficult trade-offs in the process. So it is not possible to capture everything that goes into it, but the basic process is as follows:

- The chancellor will send letters to departmental secretaries of state formally inviting submissions to be made for their departments’ spending for the years ahead. These letters will usually set out the key priorities that Number 10 and the Treasury have agreed departments should focus on, as in the launch letter for the 2021 spending review. 23 www.assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1015748/CX_LETTER_TO_ALL_SECRETARIES_OF_STATE_070921.pdf

- The Treasury will typically ask the Office for Budget Responsibility for a forecast ahead of a spending review. This will show the chancellor and prime minister whether they are going to meet their fiscal rules and, if so, how much ‘headroom’ they will have. This forecast, along with the government’s tax plans, will determine how much the government will spend over the spending review period (the overall ‘envelope’).

- Government will then begin the process of determining how to allocate the envelope. (In practice, the size of the envelope and level of taxes may be revisited later down the line to accommodate high-priority spending.) Initial bids from departments are sent to the relevant spending team within the Treasury. Some bids are sent to specialist teams within the Treasury: there are teams that will look at bids relating to capital expenditure or workforce and pay from all departments, for example. Comments are then fed back in an iterative ‘challenge process’ between the Treasury and the department.

- Treasury spending teams then produce briefings and advice for Treasury ministers to prepare them for bilateral negotiations (often led by the chief secretary to the Treasury) with departmental secretaries of state. The outcome of these decisions is then reflected in settlement letters issued by the chancellor to departments.

What is Parliament’s role in spending reviews?

Government spending is approved through an ‘estimates’ process, set out in further detail in a separate explainer. Although the House of Commons does formally approve spending, in practice it has little influence on public spending decisions in the UK. In an ‘index of legislative budget institutions’, the UK ranks in the bottom quartile of a sample of 36 countries, alongside other countries with a Westminster-style system of governance. The UK parliament’s capacity in this regard was labelled as ‘extremely limited’, with the author of the study quoting the Procedure Committee, which described the House’s power over expenditure as ‘if not a constitutional myth, very close to one’.

There have been proposals to give parliament more of a role in spending allocations, including through changes to how the spending review is scrutinised and the possible creation of a Budget Committee specifically to look over the government’s tax and spending plans. The procedure committee conducted an inquiry into the question of whether such a committee should exist in 2019, recommending that it should, though the Treasury were at the time ‘sceptical’ of the proposal and it has not yet been implemented. 24 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmproced/1482/1482.pdf

- Topic

- Public finances

- Keywords

- Budget Spending review Economy Autumn statement Tax

- Position

- Chancellor of the exchequer

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Publisher

- Institute for Government