What is a machinery of government change?

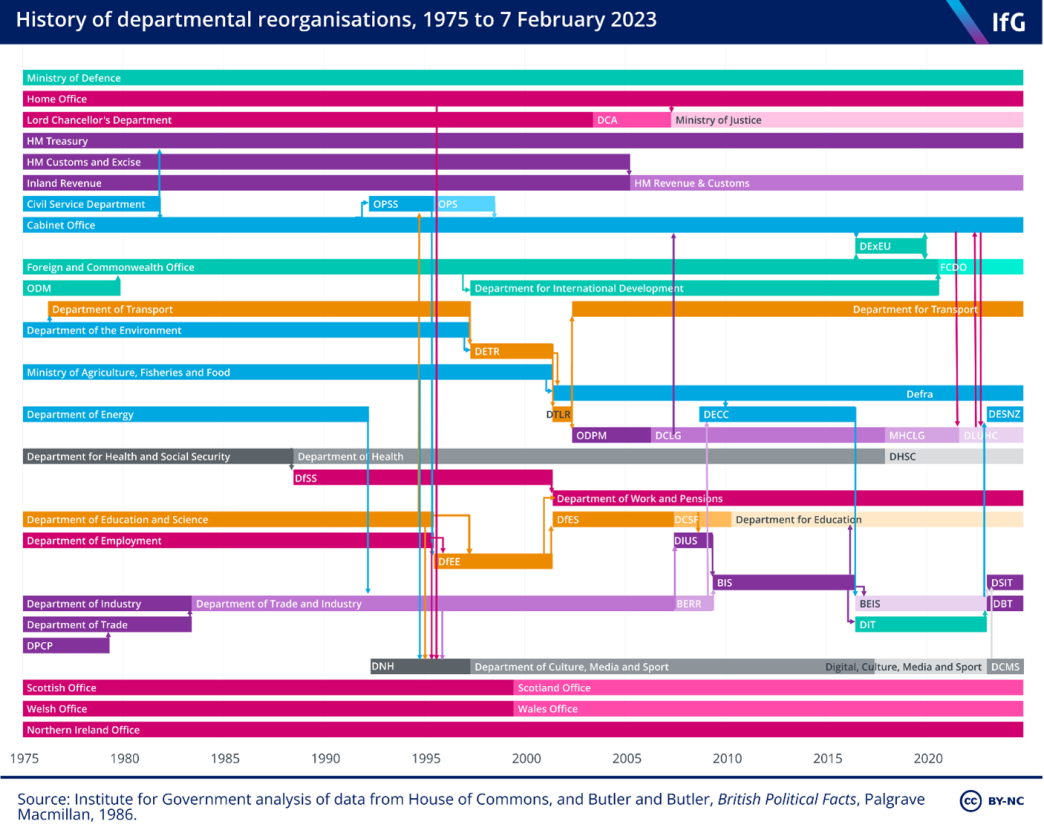

Machinery of government (MoG) changes are reorganisations which create or abolish government departments, or move functions between them.

Who decides how departments are configured?

Unlike in many other countries, there are few limits on the prime minister’s powers to change the make-up of departments. For instance, there is no requirement for the PM to seek prior approval from parliament when creating or abolishing ministerial roles.

After announcing a change in the structure of departments, the prime minister usually must lay a ‘transfer of functions order’ before parliament. 16 A transfer of functions order is an Order in Council (a form of legislation made in the name of the monarch by the privy council) under the Ministers of the Crown Act 1975. One is required for all departmental restructures which create new secretaries of state, or which change the title of secretaries of state specifically mentioned in existing legislation. However, these are generally subject to a negative resolution procedure, meaning the change is approved unless MPs explicitly raise an objection.

How often are departments restructured?

Departments are restructured fairly often. Minor changes in the remit of different ministers are common, especially around reshuffles. For instance, responsibility for the constitution and the union moved from the Cabinet Office to the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) when Michael Gove swapped departments in September 2021 17 https://www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/exethics-tsar-sue-gray-moves-to-levelling-up-department , returned to the Cabinet Office after Nadhim Zahawi was appointed minister for intergovernmental relations a year later, 18 https://www.civilserviceworld.com/professions/article/brexit-opportunities-unit-rees-mogg-beis-cabinet-office-move and then came back to DLUHC on Gove’s reappointment in November 2022. 19 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1124948/2022-12-15_-_List_of_Ministerial_Responsibili…

More major changes usually happen every few years. The most recent examples were the changes announced by Rishi Sunak in February 2023, which abolished two departments – the Department for International Trade (DIT) and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and created three new ones: the Department for Business and Trade (DBT), the Department for Digital, Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ). Before that, in 2020, the Department for International Development (DfID) was merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO).

Some policy areas are more vulnerable to change than others. The Ministry of Defence has existed in its current form, with largely continuous functions, since 1964; the Treasury, while its functions have changed, is much older. But policy areas such as climate change, industrial and digital policy move around more frequently. All three of the departments created by Theresa May in 2016 – DIT, BEIS, and the Department for Exiting the European Union (DExEU) – have since been abolished or restructured.

Why do prime ministers restructure departments?

Prime ministers will usually announce a MoG change for one of three reasons:

1. Creating a new department can be a useful way for a PM to signal ttheir commitment to a policy area – especially where this area is new or growing in importance. Gordon Brown’s government created the Department for Energy and Climate Change in 2008 to signal its commitment to tackling climate change, for instance, while the recently created Department for Science, Innovation and Technology is intended to show PM Rishi Sunak’s commitment to innovation and growth. 20 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/making-government-deliver-for-the-british-people

For this reason, many departmental restructures happen towards the start of a prime minister’s tenure. For example Theresa May created DExEU, BEIS and DIT within weeks of becoming prime minister in 2016, to signal her priorities and to help government handle post-Brexit responsibilities like trade policy.

2. Other departments may be created with the intention of improving the quality of services delivered by government – often by integrating policy issues previously handled across multiple departments. This was the motivation behind one of the largest and most significant departmental changes: the creation of the Department for Work and Pensions in 2001. This combined employment support services from the former Department for Education and Employment (DEE) with the benefits and pensions responsibilities of the then Department for Social Security (DSS), to bring customer-facing support for the unemployed and other benefits recipients together. Since its creation, the DWP has largely been left alone by subsequent restructures.

3. Finally, new departments can be created because of political imperatives or party management – for instance, a PM’s desire to distribute patronage, or please a particular colleague. For example, in 1997 the Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions was partly created to give then deputy prime minister John Prescott a large ministerial portfolio, but integrating its functions proved to be difficult and it was abolished in 2001.

How much do machinery of government changes cost?

Restructuring departments costs money. This is both in the form of up-front spending – on new IT or HR systems, communications strategies or office space – and longer-term costs such as lower productivity due to disruption or the cost of aligning the salaries of different groups of civil servants. These costs are exacerbated by the fact that there is little alignment amongst Whitehall departments on the contracts or the use of IT systems.

Previous Institute for Government work has suggested the bill for machinery of government changes can run to hundreds of millions of pounds. The creation of DWP cost around £170 million, mainly due to the more generous pay settlement given to employees of the new department. But this was an outlier. On average, the IfG estimates the upfront cost of setting up a new Whitehall policy department or a mid-sized merger will be around £15m, but with productivity costs sometimes dwarfing this.

What are the challenges of machinery of government changes?

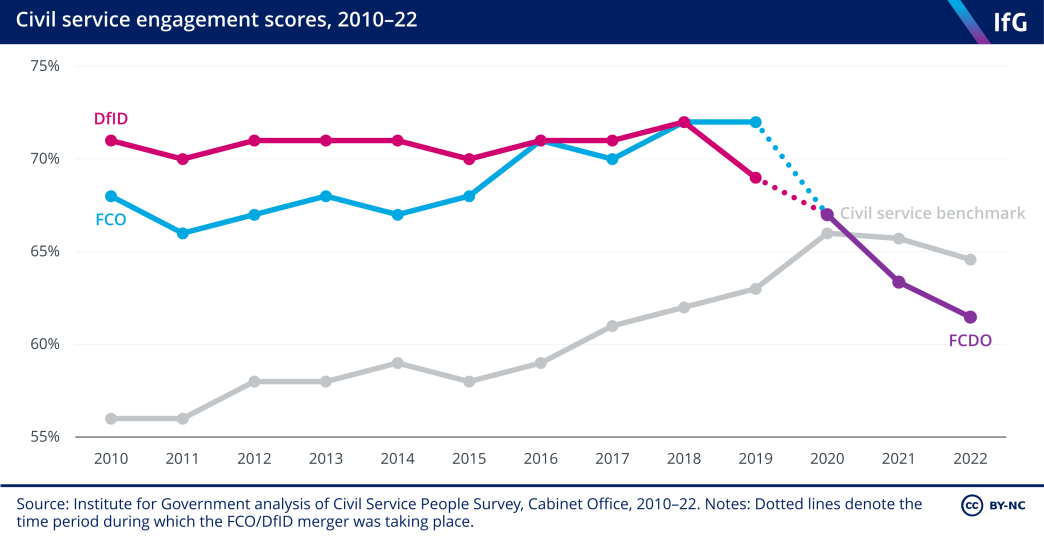

As well as financial costs, machinery of government changes can have a negative effect on staff morale and productivity. Restructures can result in hits to staff morale, especially if they feel their area is being deprioritised or that their jobs are at risk. Engagement scores for civil servants at FCDO fell below the civil service average in the years after the merger, despite DfID and the FCO having above average scores before it was announced.

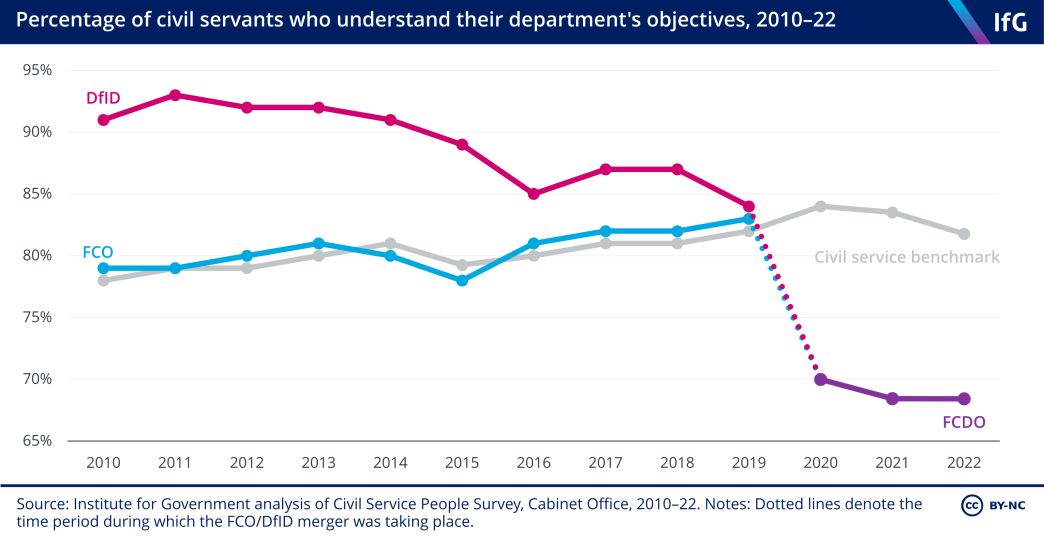

Mergers of departments can also create a new challenge: fostering a united culture in the new organisation. One senior official involved in the creation of BEIS in 2016 said that it took around two years for the new department to operate properly as a single entity. Staff understanding of their organisations’ objectives, in particular, often fall following mergers.

To combat this, the Institute has previously recommended that future reorganisations should better support staff morale, alongside “a full cost–benefit analysis and a recognition of the time needed for the new organisation to be fully functional.”

- Topic

- Civil service Ministers

- Keywords

- Machinery of government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government