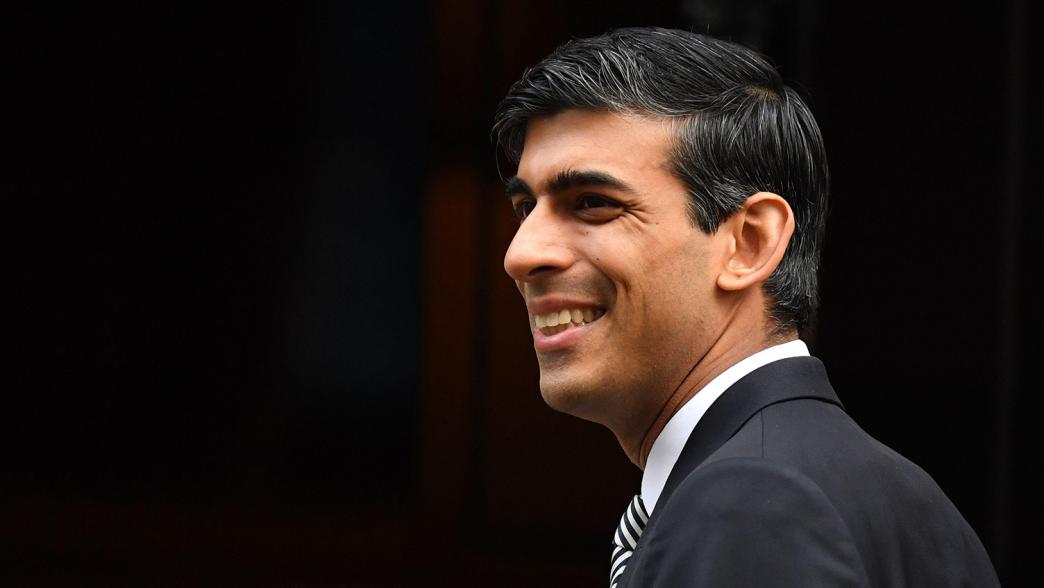

Government redesigns like Rishi Sunak’s would be helped by consistency across Whitehall

One of the reasons ‘machinery of government’ changes are so disruptive is that departmental systems are conflicting and incompatible.

One of the reasons ‘machinery of government’ changes are so disruptive is that departmental systems are conflicting and incompatible. More coherence would mean better government, says Alex Thomas

One of the reasons the Institute for Government approaches machinery of government reorganisations sceptically is because of the disruption they cause. Some restructures are – of course – worth doing. Rishi Sunak’s decisions to re-join business and trade, and to separate out energy and net zero both make sense on their own terms.

But even a sensible reform begs the question of whether it is worthwhile. Costing somewhere between £15 and £50 million, a change needs to be really worth making to outweigh the downside of disrupted HR and IT systems and rebrands. That is before factoring in the opportunity cost of departmental confusion, with a price tag that is impossible to calculate. The problem goes wider than machinery of government reshuffles. Similar costs apply to the creation, merging or abolition of other government bodies, even if edgy officials sometimes hide the true cost of disruption from reforming ministers.

This is, in large part, because of the way in which the UK’s national government has evolved. It is by constitutional design a collection of different departments, working to different secretaries of state and permanent secretaries, with incompatible administrative systems.

This doesn’t have to be the case. Imposing more consistency across government organisations would help make logical machinery of government changes smoother and less disruptive.

Strong departmental hierarchies block essential ‘back office’ improvements

One thing nobody disputes is that a modern government needs effective digital, finance, human resources and other functions. Dismissing these services as the ‘back office’ has never done justice to their importance, and the last decade has seen real progress in professionalising the provision of these services and developing a more consistent approach across departments and throughout the civil service.

However, these ‘horizontal’ functions have never sat easily with the ‘vertical’ hierarchies of government departments. Each department has a secretary of state responsible for their policy areas, and a permanent secretary accountable to that secretary of state for the performance of the department (and to parliament for the effective spending of public money).

This vertical hierarchy is why successive governments fail to develop horizontal consistency of service provision, and why departmental reorganisations must overcome a cacophony of conflicting technological and human barriers. The same confusion plays out across government arm’s length bodies and the rest of the public sector despite tentative efforts to benchmark services across different organisations. Speaking at the IfG recently Yvette Cooper, the shadow home secretary, made the point that fragmented administrative systems across police services are a direct and tangible barrier to tackling crime.

Muddled accountability means worse government

This tension between vertical accountability and horizontal administrative consistency runs through the administration of UK government and is why the head of the civil service is unable to impose common approaches to common problems. It’s why it has been so hard to build a consistent online portal for citizens to access government services, and it means that money is wasted duplicating functions in different departments. It is one reason the civil service struggles to develop skills and sustained capability in areas like data, human resources and digital, resorts to contractors and consultants, and failed to develop its own internal consultancy service. And it is why reorganising government departments is more difficult than it needs to be.

Organisational consistency across departments is not, of course, the only way to run things. But delegating the design of systems to departments and leaving secretaries of state and permanent secretaries to run their domains as they wish would be less efficient and convenient. If a consistent experience for the citizen, a pooling of expertise and skills, and an objective to maximise value for money is part of the job of government, then consistent operational standards across government are needed.

The UK government can learn from Scotland and Wales

Ministers and civil service leaders should be much clearer about where the centre of government must set consistent and high standards, and where it is beneficial for departments to go it alone. The starting assumption should be that systems and platforms are consistent across government, even as most policy decisions happen in departments.

That operational systems shape and constrain policy decisions, and policy decisions inform how systems develop is not an argument against consistency. There is something to learn from the models used in Scotland and Wales, with the devolved administrations operating much more coherently. That is partly because of their size – both are much smaller and indeed are subsets of the UK civil service itself – but also because they were set up to a plan rather than evolving over decades. The Scottish government operates more like a single department, with one person responsible for civil service operations across the whole organisation.

There are political, constitutional and bureaucratic reasons why that is hard to achieve across the UK civil service, but that is not a reason for the prime minister and cabinet secretary not to try. As Rishi Sunak counts the productivity cost of remoulding Whitehall to deliver his priorities, future prime ministers would have cause to welcome a more coherent approach to running the government before they embark on any machinery of government changes of their own.

- Topic

- Ministers Civil service

- Keywords

- Machinery of government

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Department for International Trade Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

- Devolved administration

- Scottish government Welsh government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government