Seven things we learned from the Preparing for Power podcast

The general election campaign will dominate the coming months – but time and energy must be spent on preparing for what comes after.

Whether it is Keir Starmer forming a newly elected Labour government or Rishi Sunak and the Conservatives returning to Downing Street, both parties will need to be prepared to be in power the morning after the general election. Ben Paxton sets out seven key lessons from the IfG’s Preparing for Power podcast series

What is it really like to prepare for an election, to plan for power, and to form a government?

These are the questions we set out to answer in our recent podcast series, Preparing for Power. Over six episodes we spoke to former politicians, their advisers and senior civil servants who have lived through previous transitions of government in 1997 and 2010, as well as key figures who prepared for transitions that never came. They took us behind the scenes to reveal the inside story of these tumultuous periods in British politics. These are the seven key lessons that anyone preparing for power needs to learn.

1. Access talks are all about trust

New ministers are appointed in the first hours and days after a general election is won, thrust from opposition to the top of a government department and greeted on day one by their new officials. For everyone involved, it is a step into the unknown.

Access talks – official meetings between the opposition and the civil service held before an election – give the opposition and senior officials a chance to understand a little more about who and what to expect, to build relationships and to discuss the immediate priorities for the department.

But these talks depend on trust. For the opposition to be open about how it likes to work and its plans for government – the basis for the valuable discussions that take place – it must be confident that the information won’t be leaked and will be used in good faith by the civil service.

Ahead of the 2010 election, the then Conservative shadow cabinet minister Oliver Letwin shared extensive details of his party’s plans and policies with the civil servants he met during access talks, because he trusted them to keep the conversations entirely confidential.

Oliver Letwin: “We were very open and felt very confident being very open and indeed our confidence was entirely justified. There was no suggestion any time that any of this stuff was leaked out or up”.

Letwin told us how these discussions fostered a mutual understanding that smoothed the transition process. Of course, access talks don’t always work out as planned. Post-election reshuffles can mean unexpected ministerial appointments which can result in civil servants and new ministers having to build a relationship from scratch – a situation which many guests told us is far from ideal.

Listen to Episode 1: Access talks

2. Civil servants should ready themselves for the cultural change of a new governing party

A transition of power can result in civil servants working alongside new political leaders with no prior experience of government and very different ways of working. Preparing for changes in policy is crucial, but the changes of personnel, culture and language can be just as important – and often more dramatic.

In 1997, the Treasury had prepared for Labour’s change in policy, but not this change in culture, as former permanent secretary Nick Macpherson told our podcast. We also spoke to Ed Balls, who in 1997 worked as an adviser to Gordon Brown. The new chancellor was very different to his predecessor Ken Clarke in his working style, personality, and even lunch preferences: Brown favoured a banana at his desk over the leisurely pub lunch that Clarke had often enjoyed. The relationship between the Treasury and No.10 also changed dramatically, and there was confusion about how decisions were made.

As the election approaches, civil servants shouldn’t just be preparing for what a new party in power would do, but how they would go about doing it, and why. Departments will approach this in different ways. In the Department of Education in 2010, permanent secretary David Bell asked senior officials to read Michael Gove’s book, Celsius 7/7, to help them understand the perspective Gove would bring to the department if he became their secretary of state.

Macpherson told us his advice for civil servants trying to prepare for a new political team after the election:

Nick Macpherson: “So above all, it's about listening not just to the explicit instructions you receive, but to the implicit signals which you can pick up. Both in terms of what really matters to them, what they think of their colleagues and how they want to work”

Listen to Episode 2: The civil service

Rooftop view of Whitehall and Westminster. A transition of power can result in civil servants working alongside new political leaders with no prior experience of government and very different ways of working.

3. Oppositions should prepare to maximise the political capital new governments enjoy

If there is a transition of government in 2024, then it will be only the fourth change in the largest governing party in 50 years. These opportunities are rare – so oppositions should prepare for those first days in office. With limited resources and an election campaign to fight, prioritisation is crucial. Forming a detailed policy position on every single issue is simply not possible, so an opposition should focus on a handful of key areas.

In 1997, Labour had not only a first hundred-day plan, but also a plan for the second hundred days. Jonathan Powell, then Tony Blair’s chief-of-staff, told us how this planning of key policy announcements allowed Blair to make the most of the political capital he had from winning a large majority, particularly on contentious issues such as the Northern Ireland peace process.

Jonathan Powell: “Because we had that hundred-day plan and the second hundred day plan, it gave us that political momentum that allowed us to do things like Northern Ireland. If you hadn't done that from a position of strength with political capital at the beginning, he'd never have got the peace process done.”

Listen to Episode 3: The opposition

Preparing for Power podcast series

Our six-part series takes you behind the scenes to find out how our politicians, their advisers and officials get ready for being in government.

Listen to the podcast series

4. Governing parties have some advantages at an election, but can also be constrained

The incumbent has a number of advantages in the run up to a general election, such as the power to make policy decisions and an ability to set the agenda through legislation, budgets and speeches.

But Oliver Letwin told us there are downsides to being the incumbent party, and the longer a party has been in power, the worse these can become. They are having to run the country alongside campaigning, and have less flexibility to do the thinking required to develop new policy ideas. The legacy of their time in office to date, including that of previous leaderships, can also constrain them.

Oliver Letwin: “We are now facing a situation in which the incumbent government has been around for more than 14 years and I suspect that it will find it extremely difficult to do the kind of work that oppositions can do.”

5. Manifestos should be designed to be deliverable in government, not just to win votes

Many of the people we spoke to told us that manifestos are primarily a ‘selling document’ to help a party win the election. But while there will be pressure to announce headline-making pledges to attract voters, parties should be mindful of the implications that manifesto commitments can have for a government.

Former cabinet secretary Gus O’Donnell told us that parties should focus on the outcomes they want to achieve, before committing to specific ways of achieving them. Focusing on the what of a manifesto commitment, without considering the how, risks constraining the party that wins power.

Gus O’Donnell: “What would you like the country to look like? And if they can specify that, then you start to go back and say, OK, so we're here, how do we get there? What are the best policies to do that? Let's look at the evidence”

Promising the undeliverable also risks further damaging trust in politicians, which is already at record lows. Sally Morgan, who worked as Tony Blair’s political secretary, told us how this consideration weighed heavily on the Labour opposition in 1997 but will be even more important in 2024.

Sally Morgan: “I think more than ever, actually, when trust is such a significant issue, the more that you can be straight and transparent and also say that you do have to have priorities and you can't promise everything and therefore let's be really straightforward about what we are saying we will do, and when we will do them.”

Listen to Episode 5: Making manifestos

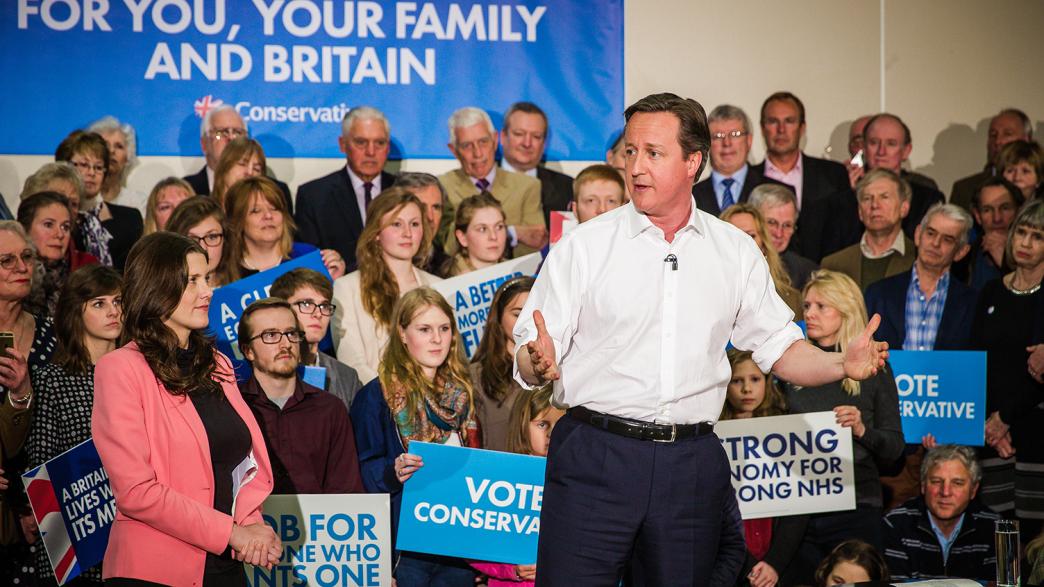

David Cameron unveils the Conservative party manifesto in 2015.

6. The UK’s overnight changeover of government makes transitions of power more difficult

Several guests described the challenge of going straight into government overnight, after weeks of exhausting, non-stop campaigning. The UK system is unusual in this practice. In the US, there is over 10 weeks between polling day and the new administration taking over; in many other parliamentary democracies, such as a Canada and Australia, there is typically a gap of several days. This allows an incoming government some breathing room for final preparations before entering power.

Jonathan Powell: “So you end up with an exhausted prime minister and staff who've been on election campaign for at least three weeks, usually much longer, no sleep that particular night then forcing them to take the decisions about nuclear weapons. Who's in the government and how the country is going to be run, it's not ideal.”

Gus O’Donnell suggested to us that a two- or three-week gap, bringing the UK in line with many similar countries, might be an improvement on our current, bizarre system of overnight transitions.

Listen to Episode 6: First days in government

7. Being in opposition is nothing like being in government

The way a party works in opposition may not translate into government. On entering power, a tight-knit team of politicians, united by their opposition to the governing party, find themselves at the top of various Whitehall departments and separated from their political colleagues – by their new roles and, more literally, by the physical distance between offices.

Harriet Harman told us how, in 1997, this change in the relationships between politicians was one of the biggest adjustments to being in government.

Harriet Harman: “I used to be popping into Gordon and Tony’s office and my other colleagues all the time. Suddenly, in government, you can’t do that. And then you realise actually how much your whole way of working is predicated on that cooperation and that’s gone.”

Entering government also means a new minister moving from a team that can sit around one table together, to running a department of thousands of civil servants. These new colleagues will provide way more resource than opposition politicians are used to, but they also work in a different way and will, quite rightly, challenge and scrutinise a minister’s ideas.

Preparations for Labour’s first budget in 1997 showcased the different ways political and civil service teams were working. Gordon Brown had spent weeks crafting a very political budget speech, but the day before the budget, his political team discovered the civil service had also been writing a speech for the new chancellor which focused on the policy detail rather than political rhetoric.

Ed Balls: “We had this terrible day from about lunchtime right through until about three in the morning, where we had two different speeches. The one which had the measures in, which Gordon didn't like, and the one he had written, which didn't have any measures in. And we had to basically blend them.”

Oppositions, and civil servants, need to be aware of this new working relationship, and proactively prepare for how they might need to change how they to operate – and the gaps in understanding on both sides that may need to be bridged.

- Keywords

- General election Cabinet Shadow cabinet Official opposition New government Civil servants Majority government Minority government Coalition government Machinery of government

- Political party

- Conservative Labour Liberal Democrat

- Administration

- Blair government Brown government Cameron-Clegg coalition government Cameron government

- Department

- Number 10

- Project

- General election

- Public figures

- Tony Blair Gordon Brown David Cameron Nick Clegg Ed Balls Rishi Sunak Keir Starmer

- Publisher

- Institute for Government