Six things we learnt from the 2023 autumn statement

The chancellor presented his autumn statement alongside the latest forecasts from the independent Office for Budget Responsibility.

On 22 November, the chancellor presented his autumn statement alongside the latest forecasts from the independent Office for Budget Responsibility. Ahead of the speech the Institute for Government set out six things it would be looking out for in the speech and documents that were published alongside. Here is our analysis of what we have learned in answer to each of these questions.

1. While noting some ‘resilience’, the OBR is more downbeat than it was in March

The new economic forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is relatively optimistic compared to the view taken by many other forecasters – but it is objectively grim. It is also much less optimistic than its last forecasts from March this year.

Growth this year is expected to be a slightly positive 0.6%, rather than slightly negative -0.2%. The OBR attributes this to the economy proving “more resilient than we expected in the face of higher energy prices, inflation and interest rates”. Inflation has persisted for longer than thought and is now expected to return to the 2% target only in 2025, a year later than expected in March.

Though there has been less economic pain this year than last, the OBR warns that next year is likely to be tougher than previously expected due to the impact of interest rates. Higher-than-expected inflation has led the Bank of England to raise its interest rate to 5.25%; the OBR had expected this to peak at 4.3%. Higher interest rates impact households directly, by raising mortgage costs and lowering house prices, and also has ‘second round’ effects as people consume less. This means that GDP growth next year has been revised down to 0.7%, much down on the previous forecast of 1.8%. Similarly, unemployment is now expected to peak at 4.6%, higher than in the March forecast, and to remain elevated for longer.

Real GDP growth is also lower in every subsequent year of the forecast. This is largely driven by a downgrade in the OBR’s assumption for the trend growth rate of GDP, from 1.8% to 1.6%. This was partly offset by a boost from economic policy – cuts to national insurance contributions, welfare reforms and a package of business support measures including full capital expensing – which increase GDP by around 0.3% in every year of the forecast. Overall, the OBR’s profile for GDP growth is closer to – though still significantly more optimistic than – the Bank of England’s November forecast.

Living standards, as measured by real household disposable income per person, are expected to fall by 3.5% between 2019/20 and 2024/25. This fall is half of what the OBR expected in March (thanks to larger than expected contributions from interest on savings) but is still the largest fall since the 1950s and, perhaps most worrying for Jeremy Hunt and Rishi Sunak, will leave real household disposable income per person lower in the run-up to the next election than in late 2019, when the country last went to the polls.

2. Hunt went for (private sector) growth again

Jeremy Hunt badged his announcements an “autumn statement for growth” and, to an extent, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) agreed with him.

The chancellor announced a package of new tax cuts for business investment (making permanent the previously temporary full expensing policy), cuts to National Insurance contributions and reforms to out of work benefits aimed at incentivising and enabling more people to find work. The OBR estimates that these measures will boost employment by 144,000 and raise economic output by 0.3% in the medium term – a slightly larger impact than the measures he announced in his March budget, which were expected to raise employment by 110,000 and GDP by 0.2%. More significantly, the OBR predicts that the measures on business investment will have an even larger effect in the longer-term.

But this was not an autumn statement for public sector growth. No extra money for government departments, despite higher-than-expected prices and wages, and the tight spending plans beyond the next election were extended for a further year. The OBR cautioned that “reducing the public capital stock as a share of GDP... if sustained… would likely also have a material, negative impact on potential output beyond the forecast horizon”. But, for now, this remains a downside risk which is not reflected in the official economic and fiscal forecasts.

Despite the new policies set out by Hunt, the OBR has downgraded its estimate for growth in the UK’s potential output – from 1.7% a year in March to 1.6% now. This is because the OBR is now more pessimistic about the average number of hours that UK workers will work, the rate at which the UK’s existing capital stock will be retired, and the prospects for productivity improvements.

3. Hunt spent a fiscal windfall in pursuit of growth at the expense of public services

As expected, a higher inflation forecast gave the chancellor a boost to tax receipts that more than outweighed higher forecast debt interest spending. If Hunt had not announced anything today – as may have been preferable, given the benefits of holding only one fiscal event a year – the deficit would have been forecast to fall to just 0.6% of GDP in 2028/29, and so on course for the lowest since 2000/01. He would also have met his most demanding fiscal rule – that debt should fall as a share of GDP in the fifth year of the forecast – with over £30bn of headroom to spare.

However, like previous chancellors before him, he rejected this notion. Rather than allow his headroom to increase he chose to spend virtually all of it, predominantly on two large tax cuts: cuts to national insurance and making full expensing of investment in corporation tax permanent. This stands in contrast to his approach last November, when forecasts worsened but he did not offset all of the underlying forecast change with a policy tightening. Such asymmetric behaviour leads to debt ratcheting up over time, as good news is spent and bad news swallowed. This is a bad way to conduct policy – especially when forecasts are so uncertain.

His priority was clear from both his rhetoric and policy announcements: to promote (private sector) growth, as he had in the March budget. And he spent large sums on tax policies which the OBR expect will boost growth, albeit modestly, by 2028. But this meant very little spending on public services, despite higher inflation eroding the real value of existing spending plans this year and next.

Ultimately, the chancellor chose to announce some tax cutting measures on the back of a further, and substantial, squeeze on public service budgets.

Autumn statement 2023

What did we learn from Jeremy Hunt's tax and spending plans? See our commentary, podcasts and events on the chancellor's tax and spending plans.

Find out more

4. The autumn statement provided no funding increases for public services

As expected, the chancellor did not make any new funding available for public services. Settlements which looked relatively generous when first announced in 2021 have been gradually eroded by inflation and higher than expected wage deals. The result is that day-to-day spending is now due to rise by only 1.9% per year in real terms between 2021/22 and 2024/25, compared to 3.6% when the settlements were first agreed in 2021. That will make it much harder for services to return to pre-pandemic performance levels.

Hunt also confirmed spending increases beyond April 2025 of only slightly under 1% in real terms every year, baking in the erosion of real budgets from higher inflation this year and next. The government’s commitment to spending increases on the NHS, defence, foreign aid and childcare implies real terms cuts for unprotected areas of spending: the OBR estimate falls of over 2% per year in real terms. Given rising demand for services – particularly the criminal justice system – that could lead to further substantial decline in performance.

History suggests that whoever forms the next government will likely top up spending when the next spending review arrives, blowing a hole in the current fiscal plans. Low budgets over the next couple of years could prompt further ‘emergency’ funding too, but short-term emergency funding pots, which make it difficult for service leaders to plan effectively and implement productivity enhancing reforms, are poor value for money. The one big public services announcement was on productivity, where Hunt set out a target for 0.5% increase per year. Productivity is an issue in many services – particularly in courts and hospitals – but nothing in the autumn statement will seriously improve the situation. Indeed, the announcement that capital budgets will be held flat in cash terms beyond 2025, which means falling in real terms, will make things worse. Public services will be left with a crumbling estate, insufficient equipment, and inadequate IT systems.

5. Infrastructure received Hunt’s attention but the government’s capital budget was cut in real terms

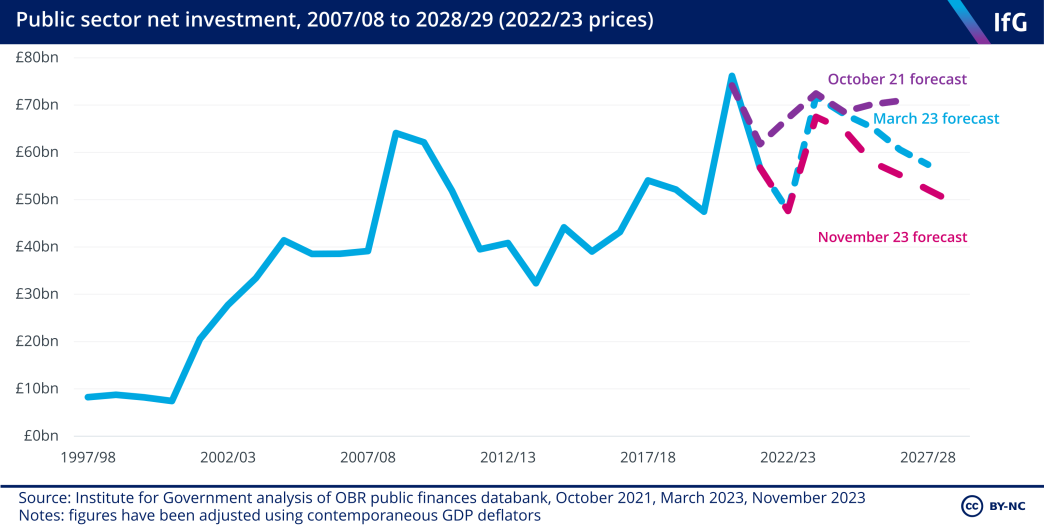

The chancellor confirmed that government capital spending (CDEL) will remain flat in cash terms from the end of the spending review period. With inflation expected to be higher over the forecast period, this implies a real-terms decrease in the government’s capital budget relative to the March forecast. The OBR forecasts that public sector net investment will fall from 2.6% of GDP in 2023/24 to 1.9% of GDP in 2027/28, compared with the March budget’s forecast of 2.1%. This is well below the target, set at the start of this parliament by Boris Johnson's government, to increase public investment spending to around 3% of national income each year.

While infrastructure did not benefit from any additional public funding (except for some small announcements, such as the space sector), it was still a significant focus of the chancellor’s speech. Hunt’s strategy has been to cut taxes (the introduction of full capital expensing is the most relevant here), reduce regulation and push forward reforms to pension schemes in order to spur greater private sector investment.

The chancellor also announced the government’s responses to the electricity network commissioner’s report 7 Electricity Networks Commissioner’s recommendations, 4 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/accelerating-electricity-transmission-network-deployment-electricity-network-commissioners-recommendations on reducing the build time for energy projects and the National Infrastructure Commission’s report on planning reforms. 8 //nic.org.uk/studies-reports/national-infrastructure-assessment/second-nia/ The OBR said that these reforms, alongside other announcements, such as those accelerating the consolidation of pension schemes, would likely incentivise additional investment in infrastructure – though did not feel it had enough certainty to quantify the potential benefits.

Infrastructure did not benefit from any additional public funding in the autumn statement.

6. Tax cuts were well designed but there is a risk the government struggles to stay the course

Jeremy Hunt announced a sizeable cut to national insurance contributions (NICs) by employees and the self-employed and – as widely expected – made permanent the previously temporary ability for businesses to offset upfront the full cost of capital expenditure against profits for corporation tax purposes. Taken together, these policies will cost the exchequer around £20bn a year in 2028/29 – though will cost rather less in the longer-term as the cost of full expensing falls.

The full expensing policy has received widespread support from businesses. It is well designed to encourage more investment in qualifying plant and machinery, although it creates a distortion away from other types of investment and increases the existing distortion in favour of debt- rather than equity-financed investment. The cut to NICs is better targeted on encouraging work that a similarly sized cut to income tax would have been, since NICs are paid only on earnings and not on other forms of income, such as pensions and investments. The larger cut in employee NICs than employer NICs would – on its own – help somewhat to reduce the distortionary effects of the different ways the Treasury currently taxes different forms of work. However, particularly for lower earners, the abolition of class 2 NICs (a sizeable tax cut for the self-employed not enjoyed by employees) will go in the other direction.

Under the chancellorships of Sunak and Hunt, the income tax personal allowance, higher rate threshold and (more recently) NICs thresholds have been frozen, rather than being uprated with inflation.

Both the full expensing and NICs policies go somewhat against the grain of previous tax changes under recent Conservative-led governments. Between 2010 and 2016, George Osborne focussed on cutting the headline rate of corporation tax, while broadening the base by reducing the generosity of capital allowances. Sunak then Hunt’s policies have gone in the opposite direction – reversing previous cuts to the headline rate but offering more generous incentives to investment.

The change in tack on employment taxes is more recent. Under the chancellorships of Sunak and Hunt, the income tax personal allowance, higher rate threshold and (more recently) NICs thresholds have been frozen, rather than being uprated with inflation. At a time of rapid price growth, this has translated into a large tax rise – expected to net the exchequer £45bn a year by 2028/29 according to the OBR. Wednesday’s announcement of a cut to NICs rates starts to reverse this trend.

The danger for Hunt – and for businesses and individuals trying to plan their future activity – is that the government may not be able to afford to stay the course on tax cuts. Hunt was only able to “pay for” these tax cuts because of higher inflation, which boosted forecast tax revenues, but he chose not to compensate public services for these higher costs. Instead he further deepened and extended the planned squeeze on already struggling public services. Hunt will be hoping that he gets more good news between now and the budget.

But if not, he will face extremely difficult choices about how to fund the already announced tax cuts, along with any other potential pre-election priorities (such as cancelling next April’s planned 6p rise in fuel duty), with public spending plans already looking implausibly low.

- Keywords

- Autumn statement Public spending Public sector Budget Spending review Tax Economy NHS Health Social care Schools Criminal justice Police Prisons

- Political party

- Conservative

- Position

- Chancellor of the exchequer

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Project

- Autumn statement 2023

- Public figures

- Jeremy Hunt Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government