Better borrowing numbers do not mean the chancellor has a tax cuts war-chest

The chancellor and prime minister should not use inflation to cut spending by the back door.

Higher inflation might provide a boost to government tax revenues, but Thomas Pope and Gemma Tetlow warn that it will also make existing – and tight – departmental spending plans appear even less plausible

The monthly public finances release is usually a low-key affair that passes all but the most committed fiscal watcher by. But last week’s numbers piqued broader interest: 10 Office for National Statistics, Public sector finances, UK: July 2023, 22 August 2023, www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicsectorfinance/bulletins/publicsectorfinances/july2023 they showed that the government is on course to borrow much less this year than the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the government’s independent forecaster, anticipated at the budget in March. This is despite interest rates now being even higher than expected at the time, which on their own increase the amount the government needs to spend servicing its debt.

The prime minister and chancellor have long indicated that they would be eager to cut taxes should circumstances allow. To date, they have been thwarted in this ambition by their own fiscal rules, the most binding of which is that debt must fall as a share of GDP in the fifth year of each forecast horizon (2027/28 as of March, 2028/29 from autumn) – a target that was met with a margin of only £6.5 billion in March. What matters, then, for the chancellor’s flexibility against those rules is not how much the government is borrowing this year, but how the outlook for five years’ time might have changed.

So what might the next OBR report, due in the autumn, reveal? New Institute for Government analysis of how the fiscal outlook has changed since March shows that the factors driving lower borrowing this year – most importantly changing expectations about inflation – are also likely to lead to a fall in forecast future borrowing. This is likely to be enough to offset the higher cost of servicing government debt, a result of the higher interest rates that are also affecting mortgage holders. We estimate that borrowing in the fifth year of the forecast could be around £10 billion lower if the OBR revises its forecast in line with the Bank of England’s, with higher inflation providing a boost to government tax revenues as incomes, spending and profits grow more quickly in cash terms.

But that will not tell the whole story: that same higher inflation will make the government’s existing spending plans appear even less plausible than they did in March. Given the current state of public services, the cost of recent pay awards and how tight existing spending plans already were, it seems likely that this or any future government will need to devote much or all of any ‘war-chest’ towards more generous spending plans unless they are prepared to scale back even further the quality and scope of public services.

Exactly how much room the chancellor will have against his main fiscal target will also depend on other factors that could affect the level of debt, most obviously recent changes in interest rates will affect the size of losses the Bank of England might make as it unwinds Quantitative Easing, (the sale of the assets the Bank has purchased to support the economy, first in the wake of the financial crisis and then coronavirus) and when those losses are incurred.

Higher interest rates are bad news for the public finances

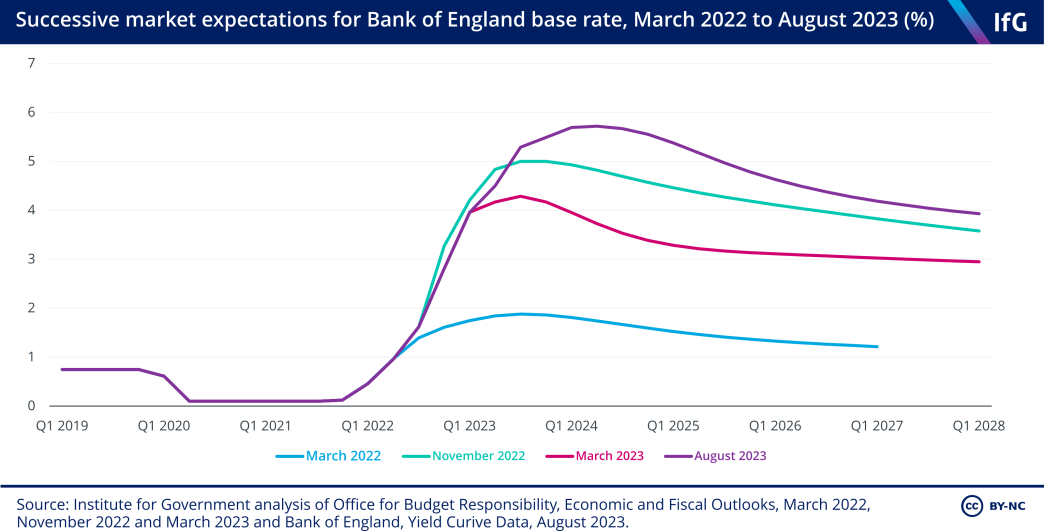

One of the main economic developments most people will be aware of since March is a rapid rise in interest rates. The Bank of England’s base rate is now 5.25%, compared with 4% at the time of the budget – a much higher increase than the forecast anticipated back in March when financial markets expected that interest rates would peak at just 4.25%. Instead they have already risen higher and are now expected to stay higher for longer.

This has implications for the government’s spending on debt interest. The rate of interest charged on government debt has increased in line with other interest rates across the economy, so servicing new borrowing is now more expensive. In addition, the Bank of England still holds over £800bn of government debt as part of its Quantitative Easing programme. These are financed at bank rate, so the Bank of England’s decision to raise the base rate has a direct impact on government spending.

Our projections suggest debt interest spending will be at least £15 billion higher than previously forecast in each of the next five years, peaking at an increase of £33 billion next year.

Higher inflation will – superficially – make the fiscal bottom line look better

Since March, there has not been much good economic news. While most forecasters no longer expect a recession this year, most now expect slower growth in 2024 because of higher interest rates, which are designed to cool down the economy. That means overall prospects for real (inflation-adjusted) economic growth look very similar now to what they did in March. 12 HM Treasury, Forecasts for the UK economy: August 2023, GOV.UK, 16 August 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/forecasts-for-the-uk-economy-august-2023

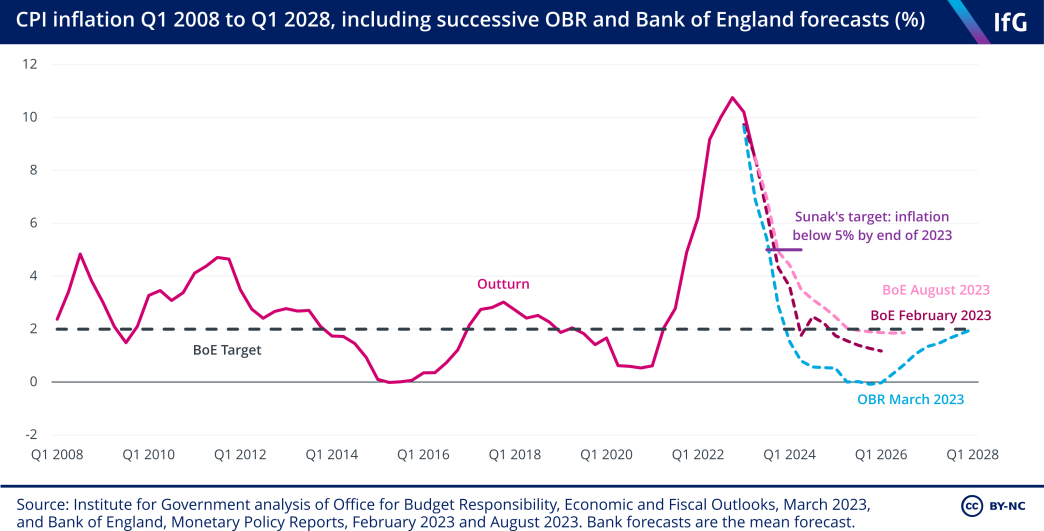

The main change in the outlook is that inflation is now expected to be more persistent. At the start of the year, it appeared Rishi Sunak would comfortably achieve his target of halving inflation by the end of the year (which requires the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to be below 5.0%). But the latest forecasts from the Bank of England now imply it will be touch and go, and inflation is not expected to return to the target level of 2% until 2025.

Inflation has been elevated since early 2022. The initial rise was driven largely by the war in Ukraine pushing up the price of imported goods like food and – most importantly – energy. But as prices went up, incomes did not, so there was no boost in cash tax revenues. At the same time government stepped in with expensive energy support packages, totalling almost £60 billion in 2022/23. The combined effect was borrowing of over £150 billion last year.

However, changes in the outlook for inflation since the start of 2023 are different. Rather than inflation being driven by higher import prices, the reason inflation is now expected to persist for longer is due to domestic factors. In particular, wage increases are averaging around 6%, which is feeding into the price of goods and services those workers produce. This type of inflation still has economic costs, including creating arbitrary winners and losers, which is why the government has a target for low and stable inflation. But it has a different effect on the government’s finances. Wages and spending are now expected to increase more quickly in cash terms, which in turn means faster-growing tax revenues.

Based on how the Bank of England has adjusted its outlook for inflation since March, and assuming this change is driven by domestic rather than imported inflation, increases in tax receipts are likely to more than counteract the fiscal costs of higher interest rates. By the end of the forecast period, when the government’s main fiscal rule applies, we estimate that the government is on course to be borrowing £10 billion less than in March. This positive impact of inflation on revenues is amplified by the government’s current tax policies. Ordinarily, income tax and National Insurance thresholds like the personal allowance increase in line with inflation. But the government has frozen these thresholds until April 2028. That means that faster wage growth pushes more and more of people’s incomes into higher tax brackets.

On the other side of the ledger, some elements of public spending will also automatically increase when inflation goes up – for example, most social security payments (including state pensions and out of work benefits) increase in line with inflation each year. But the largest tranche of government spending – departmental budgets, much of which is spent on public services – are by default fixed in cash terms. So, when inflation goes up, there is no automatic increase.

Domestically generated inflation therefore flatters the government’s bottom line by hiding a cut to departmental spending: fixed cash budgets will stretch less far if inflation is higher.

But this is only achieved at the expense of public service budgets which are already squeezed

So the improvement to the fiscal bottom line from higher inflation is something of a mirage, and would only be achieved by imposing a further real-terms cut to departmental budgets. The IfG and others have already questioned whether the spending plans currently pencilled in are credible.

The latest spending review set out detailed plans for cash spending up to March 2025. Beyond that, the government has assumed that capital budgets will be fixed in cash terms. If economy-wide inflation evolves as we project, that would imply a 3.5% cut in real-terms capital budgets between 2024/25 and 2027/28.

Day-to-day budgets also look difficult to deliver. Back in March, day-to-day spending was set to barely increase this year and next and then to increase by only 1% per year in real terms over the subsequent three years, which lie beyond the end of the current spending review. Under our new inflation projections, the picture is even more severe. We now project that the current cash plans would leave day-to-day departmental spending lower in real terms in 2027/28 than in 2022/23. When accounting for already promised, larger-than-average increases for health, defence and aid, this already implied a substantial cut to other, unprotected areas of spending. 15 Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2023, 15 March 2023, https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2023

Public services are already struggling to deliver what the public expects, and spending plans as tight as the government’s make it very difficult to achieve meaningful improvements. The pay settlements the government has reached for this year, averaging around 6%, have already imposed additional ongoing costs on departments (who will have to find the new funds from their own budgets in most cases) amounting to around £4 billion compared with what was planned for.

In recent years, the government has exhibited a pattern of pencilling in tight spending plans beyond the current spending review to make its fiscal arithmetic add up, but then – when it has come to the crunch of spelling out how that limited pot will be allocated to departments – it has ultimately allocated more money. The OBR has shown that in the run-up to the last two multiyear spending reviews, the government topped up its plans by an average of over £30 billion per year. 16 Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and fiscal outlook, March 2023, https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/OBR-EFO-March-2023_Web_Accessible.pdf , p124

We project that just compensating departments for the increase in inflation would cost £11 billion per year by 2028/29. This would compensate departments for higher pay awards and other costs but would wipe out all of any borrowing improvement and would still leave in place the implausibly tight real-terms increases pencilled in back in March. An alternative assumption, that might allow for more meaningful improvements in public services, would be to increase departmental spending in line with GDP growth beyond this spending review period. That would imply annual real increases of around 2% per year, still below the long-term average. Doing this would cost the government over £25 billion per year by 2028/29, which would mean borrowing much more than the OBR forecast than March. This would almost certainly mean missing the government’s main fiscal rule.

Inflation should not be used to cut public spending by the back door

If economic circumstances do not change much in the next two months, in the autumn the chancellor is likely to be given what looks on the surface to be a fiscal windfall. Even then, lower borrowing will not necessarily translate into greater headroom against the chancellor’s main fiscal rule. That depends on how debt changes from year to year, which is affected not just by the chancellor’s fiscal prudence but also by asset sales, some of which he has little control over. Most obviously, this includes the losses the Bank of England incurs as it unwinds quantitative easing. The scale of losses depends both on prevailing interest rates and the timing of sales. This demonstrates one of the weaknesses of this type of fiscal rule.

If the chancellor does have more room for manoeuvre against his fiscal rule, he could choose to save it and increase headroom against it – which was wafer thin in March – or he could use it to increase spending or to cut taxes. However, he should be wary. Most of any forecast improvement in borrowing is likely to be the result of higher inflation boosting tax receipts, rather than a stronger real economy. In effect much of any forecast improvement will be achieved by squeezing already-tight departmental budgets.

In the short-term, he could leave spending numbers unchanged. Until the chancellor carries out a new spending review – which could be left until after the next general election – the spending totals pencilled in for 2025/26 onwards are provisional and are not especially meaningful. The chancellor could kick the can down the road – possibly to a future chancellor – and deal with these implausibly tight totals later. But this would be imprudent. The chancellor and prime minister’s desire to cut taxes is a legitimate one, but if doing so means less spending on, and therefore lower quality or reduced scope of, public services they should explain this to the public rather than using inflation to cut spending by the back door.

- Topic

- Public finances

- Political party

- Conservative

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak Jeremy Hunt

- Publisher

- Institute for Government