Rishi Sunak’s five pledges: one year on

How much progress has the prime minister made towards meeting his five pledges?

In a speech last January, Rishi Sunak set out five pledges and declared that he fully expected "you to hold my government and I to account on delivering those goals." The IfG experts review how much progress the PM has made in the last 12 months

One year ago, on 4 January 2023, Rishi Sunak set out his five pledges. These were to:

- Halve inflation

- Grow the economy

- Get debt falling

- Cut NHS waiting lists

- Stop the boats

Sunak had been prime minister for just over two months, having moved into Downing Street at the end of a turbulent 2022 – a year that began with Boris Johnson mired in scandal, and would only end with Sunak as prime minister after Liz Truss had taken the reins long enough to witness the effects of her September ‘mini budget’, before resigning in October.

It was against this backdrop that Sunak gave his speech. 24 Prime Minister’s Office, Prime minister outlines his five key priorities for 2023, 4 January 2023, retrieved 15 December 2023, www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-outlines-his-five-key-priorities-for-2023 He wanted to show he could be trusted on the economy, unlike Truss, and be trusted to deliver, unlike Johnson. Voters should, he said, hold his government ‘to account on delivering’ his pledges that, in his words, reflected ‘the people’s priorities’.

Some were designed to be hit relatively straightforwardly: inflation was already forecast to halve in 2023 and that debt should fall was an existing fiscal rule. Some were designed to give him maximum wiggle room: he could technically claim success if just one fewer person was waiting for an elective operation than in January 2023 and if the economy grew by just 0.1% (at the time the economy was forecast to contract in 2023).

The most risky pledge was to ‘stop the boats’. And while Sunak tried to link this to passing legislation on small boats, in practice the widespread use of the slogan has left him little room to try to claim a purely technical success.

He was not specific about the timeframe for delivering his pledges, aside from his pledge to halve inflation by the end of the year. He did however ask voters to judge his government on ‘the results we achieve’ and so, as we enter what the prime minister has said will be a general election year, this short insight looks at the progress and likely next steps for his five pledges in 2024.

Suank’s record is mixed. He has achieved his inflation pledge, and is on track for the economy to continue growing in 2024, albeit slowly. Debt is forecast to fall – in 2028/29 – but this relies on implausibly tight spending plans for which we have little detail, and therefore this pledge seems in doubt. Both cutting NHS waiting lists, the pledge over which Sunak had the most direct control, and stopping small boats crossings, the pledge he seemed least likely to meet last January, are off track.

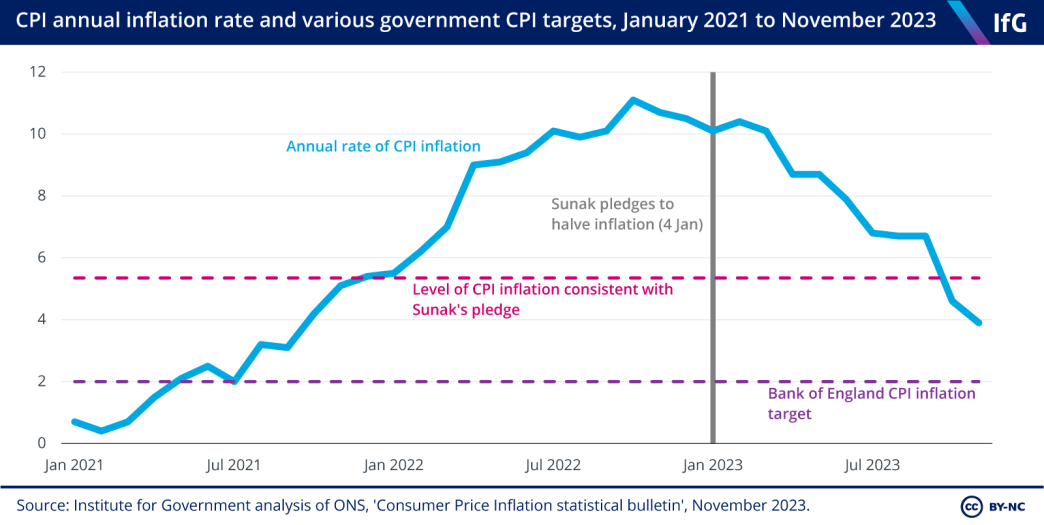

Halve inflation

Sunak pledged to “halve inflation this year to ease the cost of living and give people financial security”. At the time of his speech the latest available data showed that CPI inflation had reached 10.7%. This meant Sunak needed to see the rate of CPI inflation fall below 5.35% by the end of 2023 to claim success on this pledge.

This pledge was separate to, and technically less ambitious than, the target for the Bank of England to keep CPI inflation at 2%, also set by the government. 26 Autumn Statement 2023’, 22 November 2023, retrieved 15 December 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/monetary-policy-remit-autumn-statement-2023/monetary-policy-remit-autumn-statement-2023 The Bank has had an inflation target since it was made independent in 1997, when it took on delegated responsibility for controlling inflation, through monetary policy, from the government.

The prime minister’s pledge did not change this, nor did it affect the Bank’s approach to monetary policy, the most important lever for reducing inflation. Given this institutional setup for managing inflation, it is not clear that the existence of this target or government actions have made a substantial difference to inflation in addition to the large rises in interest rates undertaken by the Bank of England, perhaps other than not pursuing particularly reckless fiscal policy.

Has inflation halved?

Yes. CPI inflation had fallen to 4.6% in the 12 months to October 2023; it has fallen further since to 3.9%. And it is forecast to continue falling in 2024 – albeit at a much slower rate than we saw in 2023.

Has the cost of living eased?

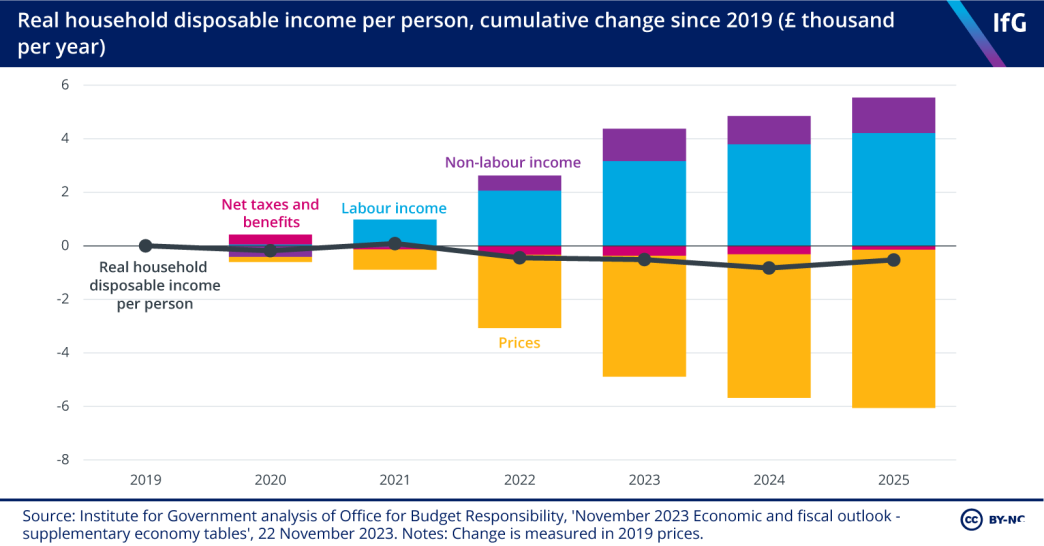

Not meaningfully. Any lowering of inflation will help but it is not possible to say that the cost of living has ‘eased’ this year – after all, lower inflation does not mean consumer items become cheaper, just that their prices rise less slowly.

And indeed the latest forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) show that cost of living pressures have continued to grow this year. Real household disposable income per head (RHDI, the headline measure of living standards) will contract this year and next as price rises continue to outpace increases in labour income. The overall 3.5% peak-to-trough drop in RHDI between 2019-20 to 2024-25 is the largest reduction in real living standards since ONS records began in the 1950s.

Grow the economy

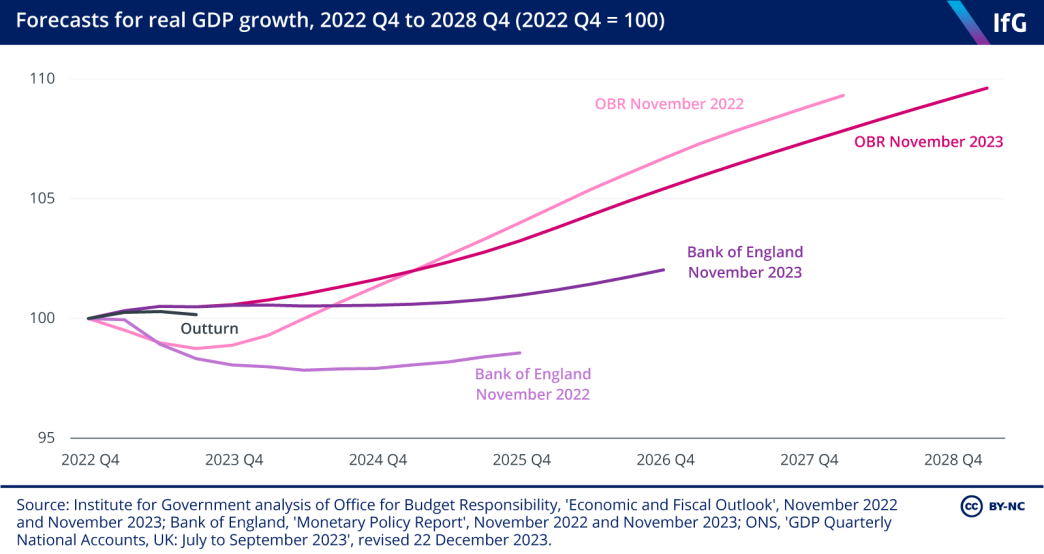

The second of Sunak’s pledges was “to grow the economy, creating better-paid jobs and opportunity right across the country”. The implied target is for the economy to grow in real terms, which is not particularly ambitious: the economy has only failed to grow year-on-year eight times since 1949. 30 ONS, ‘Gross Domestic Product, Year on Year growth, CVM SA%’, www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/timeseries/ihyp/pn2 Yet even this seemed to be in some doubt. Both the OBR and Bank of England forecast that the economy would contract in 2023 in their forecasts in late 2022 and early 2023.

Has the economy grown?

Yes. The economy has outperformed those uncomfortable early projections, and it’s likely Sunak will be able to say the economy grew in 2023. An official GDP growth figure for the year will not be available until 2024, but both the Bank and OBR now expect it will be around 0.5%. This specific figure now looks optimistic due to recent ONS revisions to GDP for 2023, which showed GDP fell by 0.1% from July to September. It is now possible that the economy will be in technical recession at the end of 2023, 31 Defined as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. If GDP growth in Q4 2023 is also negative then the UK will therefore be in a technical recession. but growth over the whole year is still likely to be slightly positive, though still somewhat anaemic in historical context: average annual growth since 1949 was 2.4%, and even since 2010 has averaged 1.6%.

This year, levels of growth for 2021 and 2022 were revised upwards by the ONS which means the UK’s economic performance since 2019 is in the middle of the pack alongside its international peers, whereas previously data showed that the UK was the only country in the G7 not to have recovered to its pre-pandemic level by the end of 2022. While this is good news for the UK, and challenges a prevailing narrative of UK economic underperformance since 2019, it entirely reflects growth before the pledge was made rather than being a result of government action since.

Has this created better-paid jobs and opportunity right across the country?

Not obviously. Both the Bank of England and OBR expect employment to have risen during 2023, but the unemployment rate will also be higher. And across the whole year, average earnings are expected to not quite match inflation, making it hard to claim that the average worker is ‘better paid’ in 2023 than they were in 2022. Sunak’s inclusion of ‘right across the country’ would need regional data to assess its success, which is not yet available.

Will the economy grow in 2024?

Probably, but not by much. Forecasts are pessimistic about growth for the upcoming year, and the years after, due in part to the impact of high interest rates. The latest OBR forecast expects GDP growth of 0.6% in 2024, similar to that in 2023 but again sluggish by historical standards. The Bank of England and the OBR expect sustained growth beyond next year to be around 1.1% and 1.6% respectively (that is, at best returning to the post-2010 average).

Governments have little control over how quickly the economy grows from one year to the next. Factors such as global economic conditions, the price of key commodities like oil and the Bank of England’s monetary policy decisions are all likely to be more consequential than any government policy in the short term.

But Sunak and his chancellor Jeremy Hunt are right to have identified that growing the economy is important. Weak productivity growth since 2010 explains many of the fiscal problems the government faces today, as it has meant slower growth in revenues and so less money for public services. And the government has made some positive steps to create the circumstances for economic growth in the UK. Changes to both childcare and the tax treatment of business investment have led to the OBR increasing its projection for GDP in five years by 0.5%.

But many of the measures announced in the autumn statement were affordable within the government’s fiscal rules only due to very tight spending plans, particularly for investment which will fall in real terms. While the government has focused on supporting private sector investment, it is proposing to cut spending on economic infrastructure that could benefit the economy and investments that could make public services more productive. 32 //obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-november-2023/

The prime minister and chancellor may seek to make further changes in fiscal events this year, most obviously in the budget in March. While any changes made this year are unlikely to actively deliver growth by the time any election takes place (January 2025 at the very latest), the events may provide Sunak with some improved forecasts for growth that they can take to the country.

However, with one eye on an election, the prime minister should avoid the sugar rush of demand-boosting pre-election tax cuts that would harm the UK’s longer-term economic prospects.

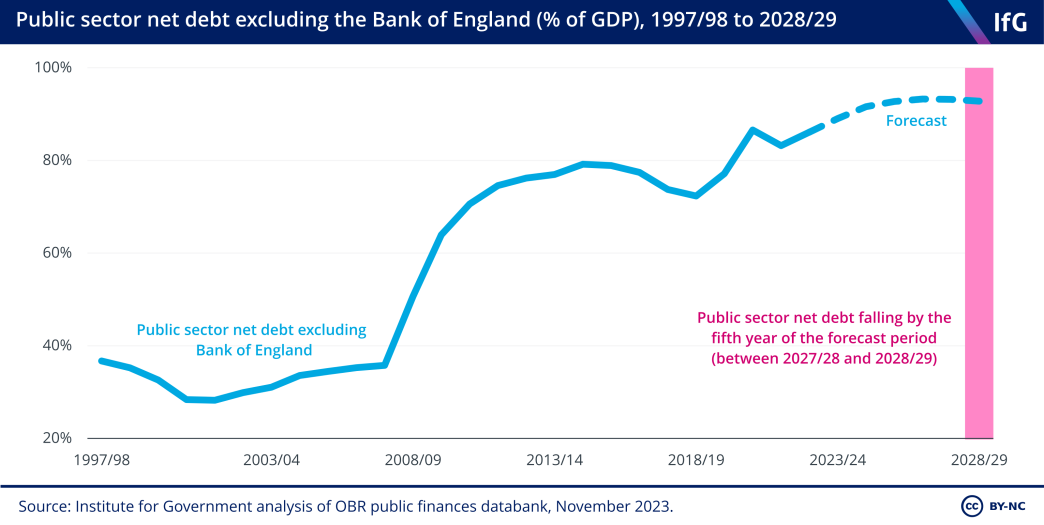

Get debt falling

Sunak said he will “make sure our national debt is falling so that we can secure the future of public services”. Using the standard measure of debt as a share of GDP, this pledge has not yet been achieved.

Has debt fallen?

No. The latest figures show that the headline measure of public debt (public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England, ‘PSND ex’) rose from £2,216bn at the end of December 2022 to £2,419bn at the end of November 2023, or from 85.1% of GDP to 88.3% of GDP. This is despite claims by the prime minister that “debt is falling” or “we have indeed reduced debt” – claims that have been subject to criticism by Robert Chote, chair of the UK Statistics Authority (UKSA), for being potentially misleading. 35 //uksa.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/correspondence/response-from-sir-robert-chote-to-sarah-olney-mp-public-sector-debt/

Is debt forecast to fall?

Yes. One of the government’s fiscal rules is to ensure that PSND ex is falling by the fifth year of the forecast period. The latest forecast from the OBR suggests that, on stated government plans, this rule will be met: debt is forecast to be 93.2% of GDP in 2026/27 and 2027/28 but then fall to 92.8% in 2028/29. But it may be close: the OBR estimates that there is just a 56% chance, given the uncertainty around the latest forecasts, that this modest fall in debt will actually happen.

Is debt really likely to fall?

Doubtful. The chancellor spent his additional headroom on tax cuts in November, while he could have instead used it to reduce debt, or invest in public services – the other key factor mentioned by Sunak as part of his debt pledge. The plans pencilled in for public spending beyond 2025 in order to meet his fiscal rule, in conjunction with the government’s other commitments, imply real-terms cuts in spending of 4% per year in services, outside the NHS and schools. 36 //obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/E03004355_November-Economic-and-Fiscal-Outlook_Web-Accessible.pdf This would mean further deterioration in the performance of already-struggling services and would not seem to be consistent with “securing the future of public services”.

In practice, however, these plans are unlikely to be delivered. Successive chancellors have pencilled in tight overall spending plans beyond spending review periods before finding more money to allocate to services at spending reviews, when they are forced to decide where cuts need to be made. In spending reviews since 2015, this uplift has been around £20 billion to £30 billion per year, more than enough to set debt on a rising path as a share of GDP. There are also other policies which the current forecasts assume will happen but are very unlikely to be delivered. In particular, fuel duties are due to increase by 5p per litre and increase in line with inflation, but these increases have been planned and cancelled for each of the last 13 years.

The government’s forward-looking fiscal rule only ever requires debt to be on course to fall in the fifth year of the forecast. These rules encourage governments to announce temporary giveaways that increase short-term borrowing before the fiscal rule applies, and to do this consistently as the rule rolls forward. This dynamic is likely to be at play over the next year, not least in the lead-up to the next election when the short-term incentives to prioritise electorally popular tax cuts over longer-term decisions on debt and public spending will only grow.

As a result, even though debt is currently on course to fall as a share of GDP in 2028/29 on the basis of stated government policy, the government is unlikely to follow through with those stated policies and it is therefore doubtful that debt will in fact fall in that year.

Cut NHS waiting lists

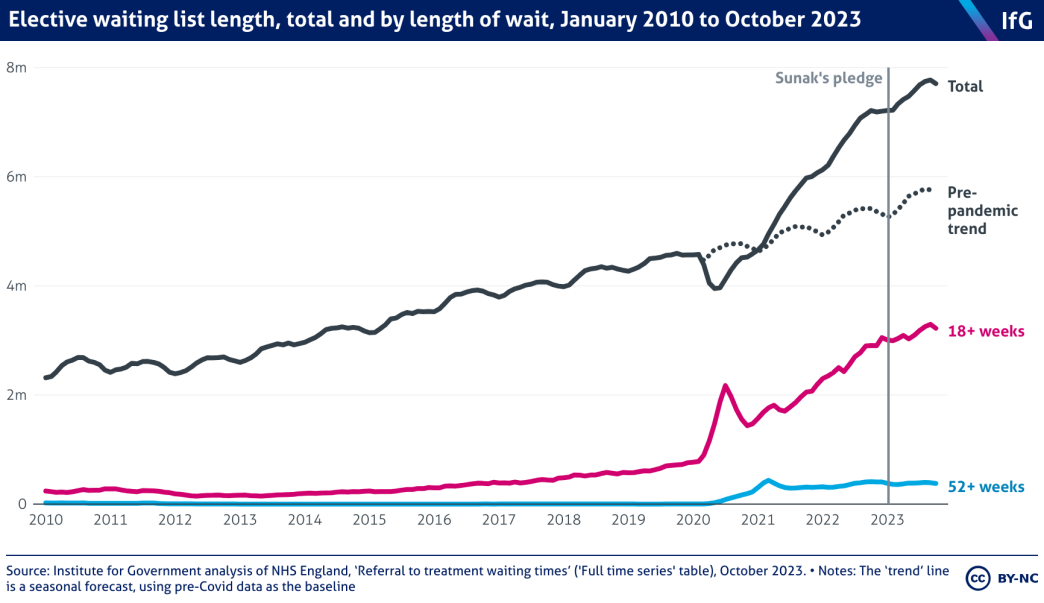

When Sunak made his pledges, the elective waiting list stood at 7.21m incomplete cases. That level itself was historically high, having increased 58% since January 2020. While the sharp increase is in large part due to the impact of the pandemic, waiting lists have been increasing year on year since April 2012.

Have waiting lists been cut?

No. The situation has in fact worsened since Sunak made his five pledges. The elective waiting list in England did fall modestly, to 7.71m, in October 2023 (the most recent month for which we have data) but that is still close to half a million cases higher than in January. Hitting this target before the end of the parliament was always going to be difficult, but has been made harder for several reasons.

Waiting times for emergency care were also at their worst level on record when Sunak made his pledge. A&E waiting times in England have very marginally improved in the past year, with 55.4% of people seen within four hours in November 2023, up from 54.5% in November 2022, but this remains far lower than pre-pandemic levels, and is way off the government‘s 2023/24 target of 76%.

Why have NHS waiting lists continued to rise?

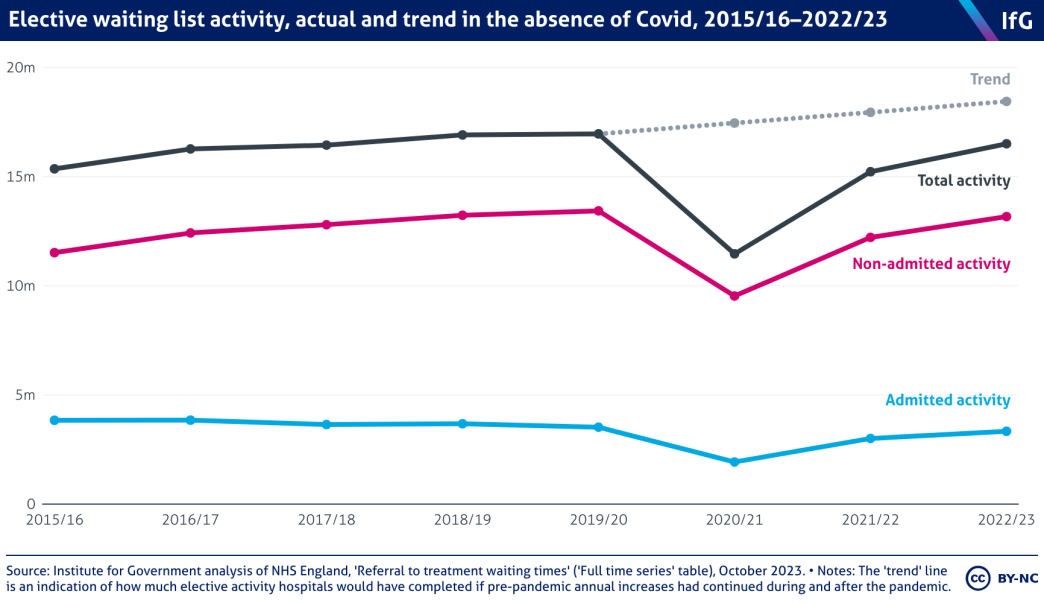

Despite record funding and staffing levels, the NHS has not returned to trend levels of activity after the pandemic due to pre-existing and long-running productivity issues. Covid certainly worsened the picture, but it mostly exacerbated pre-existing issues, namely underinvestment in capital, worsening staff morale and a lack of management capacity. This means that despite more than 15% more doctors and nurses in hospitals compared to February 2020, elective activity in 2022/23 was 2.7% lower than in 2019/20 and more than 10% lower than it would have been if pre-pandemic trend increases had continued.

This reduced activity has made it harder to work through the elective waiting list. Activity is slowly improving, but likely not quickly enough to allow the government to hit its elective target.

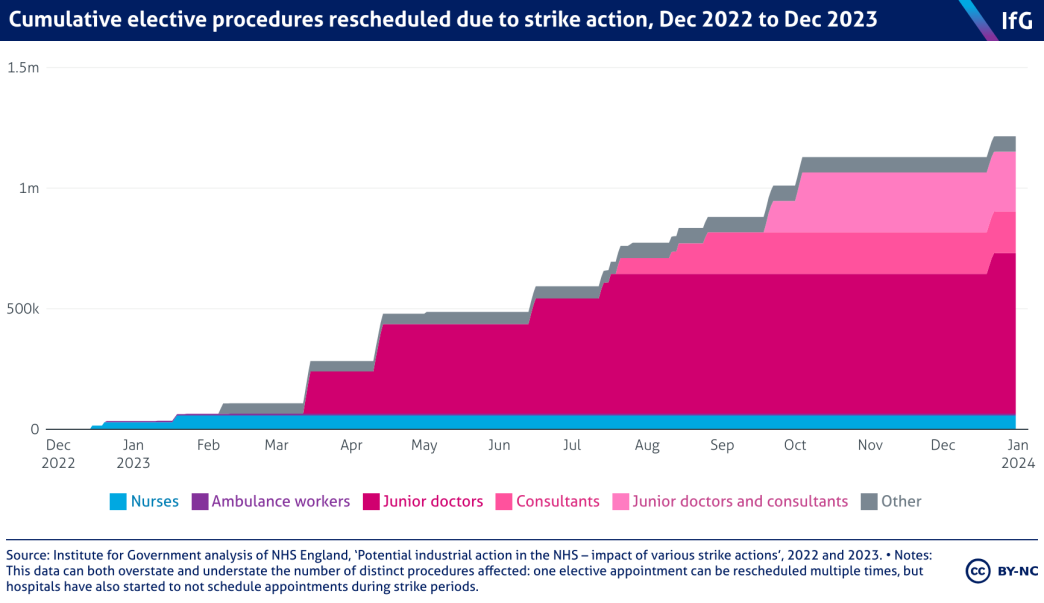

Industrial action has also increased the elective backlog, with hospitals being forced to cancel or reschedule more than 2m appointments since December 2022. But while the government is right to attribute poor elective performance (at least in part) to striking NHS staff, the government’s approach to negotiations has likely extended the length and severity of industrial action in the health service (and indeed across all public services).

A year on, the government has resolved industrial disputes with the ‘Agenda for Change’ workforce, which includes nurses, and negotiated a pay offer with the British Medical Association’s Consultants Committee, which consultants are voting on.

But no agreement has yet been reached with the BMA for junior doctors, who have announced further dates for industrial action and whose strikes to date have been the most consequential for the elective backlog: as of December 2023, more than half of all rescheduled appointments (54.8%) were due to industrial action by junior doctors alone, with a further 20.4% from joint strikes by junior doctors and consultants. 41 NHS England data, ‘Potential industrial action in the NHS – impact of carious strike actions’, 2023. Ongoing strike action over winter will be incredibly disruptive as they will coincide with the peak of the now-annual ‘winter crisis’, making further progress on cutting waiting lists in the near future even more difficult.

NHS finances have also been under immense strain in 2023/24. 42 Financial performance update, NHS England, 27 July 2023, retrieved 15 December 2023, www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/financial-performance-update/ High inflation has increased costs and ongoing strike action has forced organisations to pay higher rates for temporary staff and lose income due to reduced activity. A request in November for funding to close its £1.2bn deficit saw the NHS receive only £100m and receive permission to re-allocate up to £500m of its existing capital budget and £200m of ‘winter pressures funding’. The NHS has since downgraded its elective activity target for 2023/24 from 107% of 2019/20 levels to 103%. 43 Addressing the significant financial challenges created by industrial action in 2023/24, and immediate actions to take, NHS England, 8 November 2023, retrieved 15 December 2023, www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/financial-performance-update/

This was a legitimate decision for the government to take, but one that will almost inevitably reduce the likelihood of hitting its target.

Can waiting lists be cut before the election?

Unlikely. Meeting this target by January 2025, the latest possible general election date, would require cases to fall at a rate not seen over a 12-month period since March 2009. According to the most optimistic scenario in work carried out by the Health Foundation – which assumed no strikes after October 2023, an outcome which will no longer happen – the waiting list would still be more than 500,000 cases higher in January 2025 than in January 2023. 44 when will it peak?, Health Foundation, no date, retrieved 15 December 2023, www.health.org.uk/waiting-list

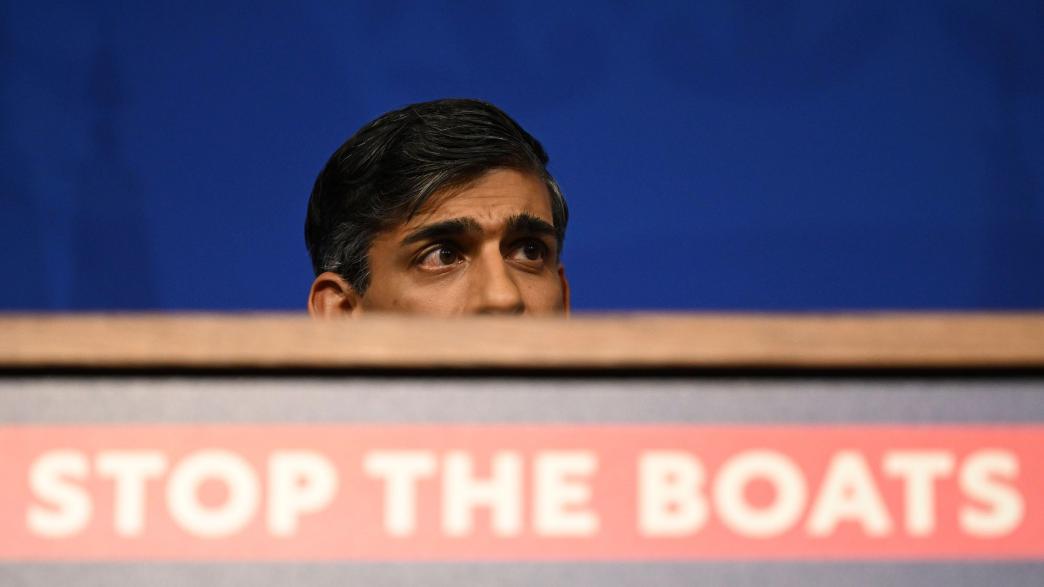

Stop the boats

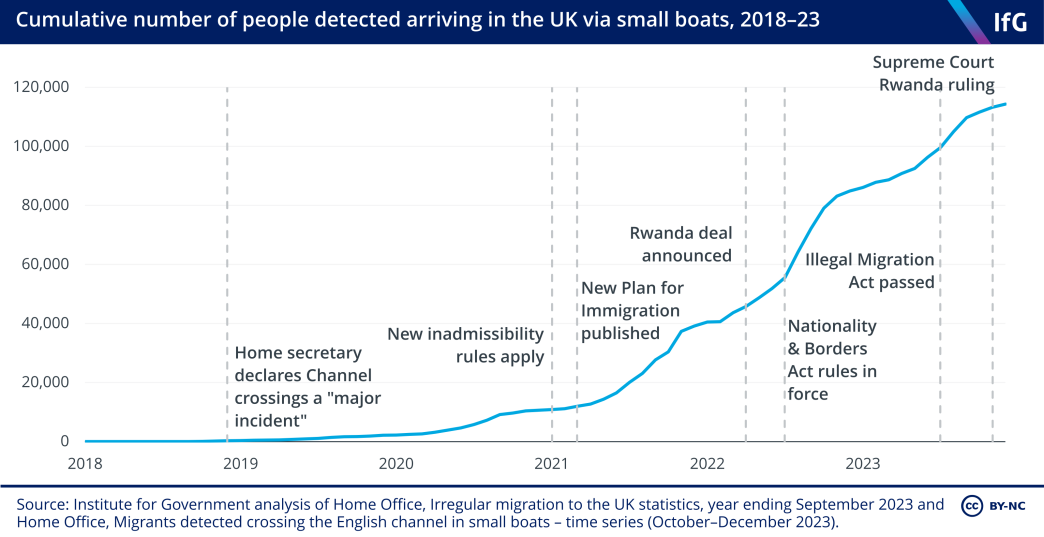

Sunak’s speech was unequivocal about his commitment to “stop the boats” – small vessels carrying people, many of whom will go on to seek asylum in the UK, across the Channel. Sunak said that, by doing so, the government would “tackle the unfairness of illegal migration”. He went on to state his intention to “pass new laws to stop small boats, making sure that if you come to this country illegally, you are detained and swiftly removed”.

The pledge was made in response to the number of people arriving by small boat increasing sharply in recent years, from the low hundreds up to 2019 to some 45,755 in 2022, and following successive unsuccessful attempts to address the issue by Boris Johnson’s government.

Has the government managed to ‘stop the boats’?

No. Though crossings are down, the prime minister did not pledge to reduce crossings but to stop them, and the problem of small boat crossings has not gone away. Just under 30,000 migrants were detected crossing the Channel in 2023. Though Sunak can point to a 36% reduction on the same period in 2022, this is largely due to the marked reduction in the number of Albanians arriving by small boat – from 9,037 in Q3 2022 to just 28 in Q1 2023 – following his successful returns agreement signed with the Albanian government in late 2022. The rate of arrivals from countries other than Albania increased by 11% in the first three quarters of 2023 compared to the same time in 2022.

How does the government intend to make progress on stopping the boats?

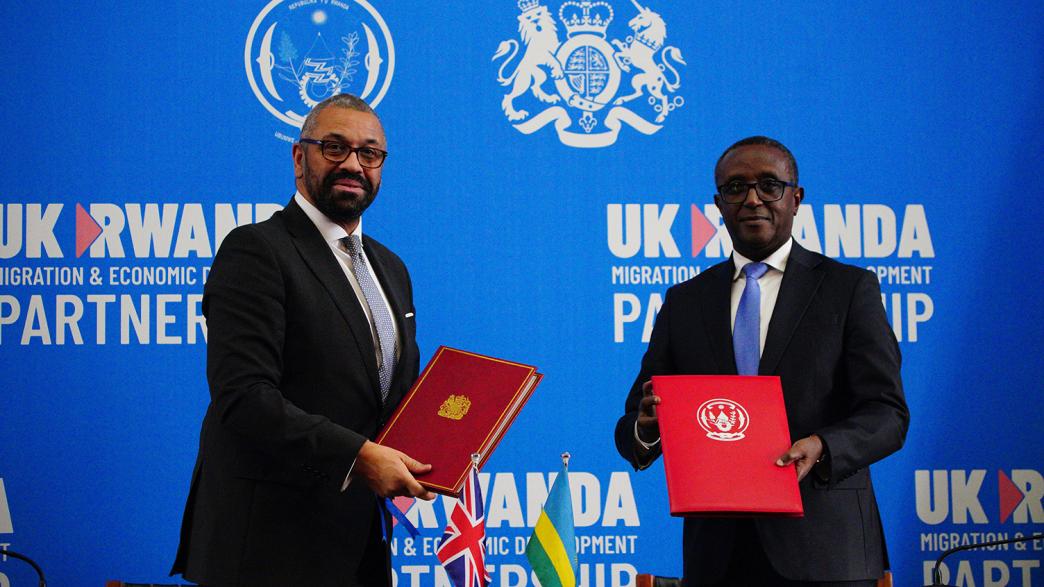

The government’s strategy is to make anyone arriving in the UK by ‘irregular means’ inadmissible for asylum in this country and remove them, either to their home nation if deemed safe or to a safe ‘third country’. The home secretary was given the power to do this in the Illegal Migration Act 2023.

This fulfils Sunak’s commitment to “pass new laws” on the issue. But that was the easy, or easier, bit. Most of the act is yet to be implemented for the simple (but fundamental) reason that the government has nowhere to send most people arriving by small boat. The biggest nationality groups crossing the Channel are from Afghanistan, Iran, Syria and Iraq – who cannot be returned safely to their home countries, and therefore would need to be sent to a safe third country.

The government has long hoped Rwanda would provide just such a safe third country, where they could apply for asylum, but protracted legal battles, and a Supreme Court ruling that Rwanda is not safe, have stymied Sunak’s plans. In response, the prime minister has upgraded the UK’s agreement with Rwanda to ‘treaty’ status, and introduced the Safety of Rwanda Bill to assert that “Rwanda is a safe country”.

The bill is contentious: it asks parliament to disagree explicitly with the facts as the Supreme Court found them to be (just weeks earlier) and if passed into law is likely to prove contrary to the UK’s international obligations. It becoming law is not a given: there are more Commons stages to go in the new year and it will likely face slow progress in the Lords. And if it passes, further legal challenges on individual cases and at the European Court of Human Rights are expected.

Can Sunak ‘stop the boats’ before the election?

Almost certainly not. Even if all the legislative hurdles are passed and flights get off the ground, Rwanda would only have the capacity to take a few hundred people, at least for the foreseeable future. And Sunak’s entire small boats strategy is based on the assertion that, by threatening to remove a comparatively small number of asylum seekers to another country, many more would be deterred from crossing the Channel in the future. There is simply no evidence that this would work – as the Home Office permanent secretary, Matthew Rycroft, reiterated to the Public Accounts Committee in December.

The government has pursued the Rwanda plan as if it were a silver bullet solution and has focused on it at the expense of policies with a longer-term prospect of success: international cooperation, community sponsorship and expanded legal routes.

- Political party

- Conservative

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak Jeremy Hunt

- Publisher

- Institute for Government