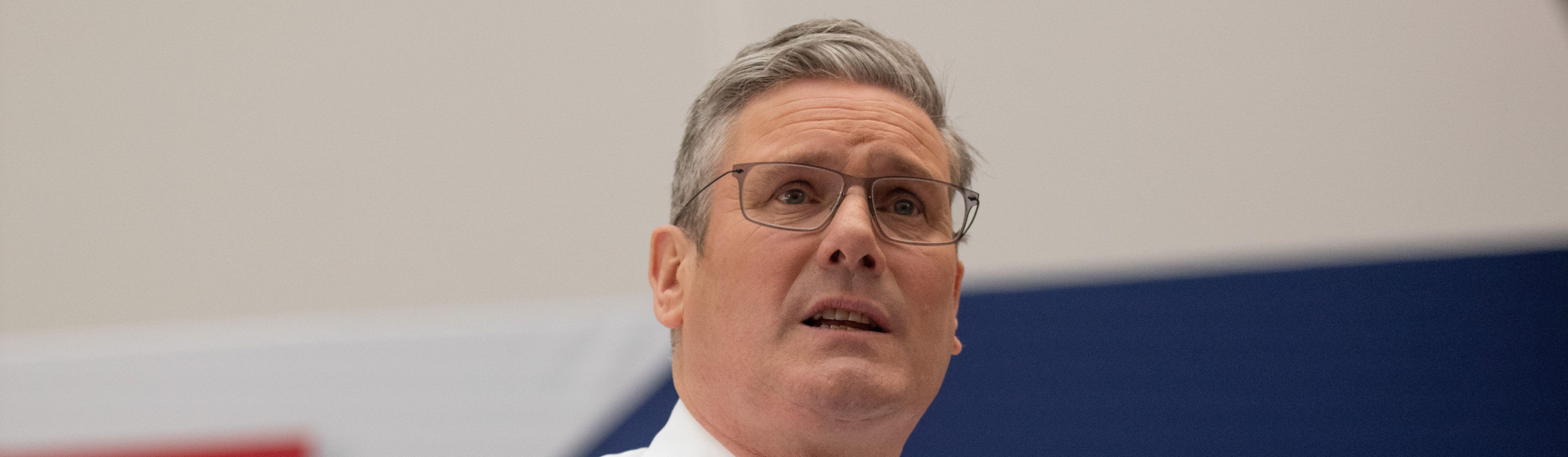

What do Keir Starmer’s five missions reveal about how Labour would govern?

A team of IfG experts assess whether Starmer’s "five bold missions" stack up

With the Labour leader pledging his “five bold missions will form the backbone of Labour’s election manifesto”, a team of IfG experts assess whether Starmer’s statement stacks up

Keir Starmer’s pledge to get the UK’s growth rate to the highest sustained level in the G7 by the end of Labour’s first term is extremely ambitious.

A zero-carbon electricity system by 2030, five years before the government’s aim, is the most clearly defined of Labour’s targets.

Given the state of the NHS, it is unsurprising that Keir Starmer included the health service in his five missions.

On crime, Starmer’s pledges include ‘reforming the police and justice system, to prevent crime, tackle violence against women, and stop criminals getting away without punishment’.

All we really know about Labour’s education policy is that they want to invest in childcare.

The Labour leader covered much ground in his speech but his central argument was that many of the challenges the UK faces – from achieving sustained growth to fixing the NHS – can only be addressed over long timeframe, and through fundamental reform.