Five per cent spending cuts will be difficult to achieve

The extent of the savings planned by the government might be difficult to achieve

While the extent of the savings planned by the government isn’t unexpected or unprecedented, Nick Davies warns that it may be difficult to achieve and is unlikely to free up enough money to meet the government’s other priorities.

There is nothing surprising about the prime minister’s request that all departments identify savings worth up to 5%. Money is tight and the government has already promised to protect important areas of public spending.

The figure is in line with IfG predictions. Published last November, our Performance Tracker report, produced in partnership with CIPFA, calculated that unprotected spending would need to fall 5.3% between 2020/21 and 2023/24 if the government were to stick to its existing plans for overall spending and meet its commitments to protected areas – the NHS, schools, defence and overseas aid.

But identifying the number is far easier than identifying where the cuts will fall.

The 5% cuts are smaller than previous spending rounds

In a joint letter with Chancellor Sajid Javid, Boris Johnson has explained that the savings will allow the government to focus its “efforts towards the things which matter most: strengthening our NHS; making our streets safer; and levelling up opportunity across the country”.

The savings are less than those set out in the 2010 and 2015 spending reviews. In 2010, the government planned overall cuts to day-to-day spending of 6.0%, but 16.4% for unprotected areas. In 2015, the plans were for cuts of 1.9% and 9.9% respectively.

As Boris Johnson’s predecessor found, however, the best laid plans of Whitehall may not survive contact with political reality.

Delivering these spending cuts will be harder than agreeing where the cuts should be made

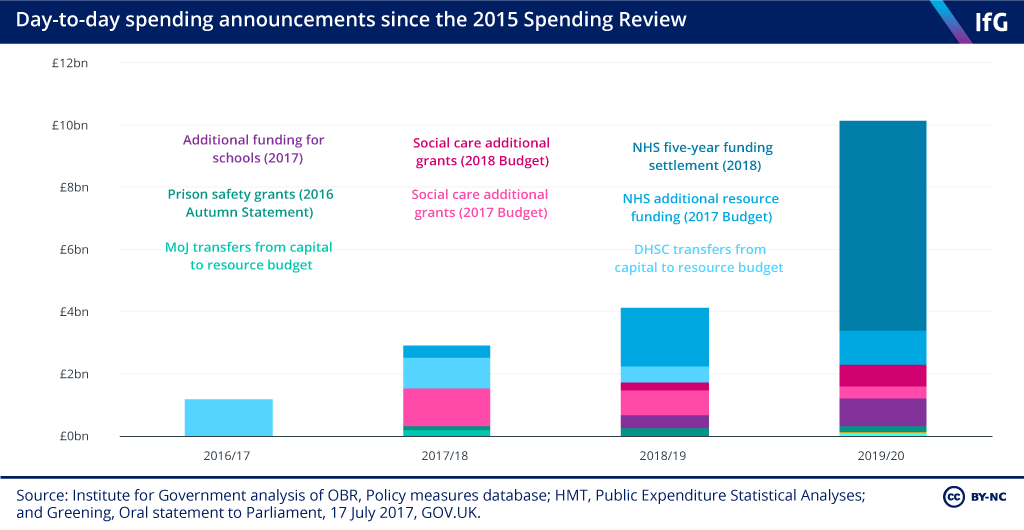

The May government committed to delivering the spending cuts planned in the 2015 spending review, but, in 2019/20 alone, ended up spending £9.4bn more on nine public services. Concerns about the performance of the NHS, social care, schools and prisons resulted in the government pumping in emergency funding to relieve pressures.

The new government is likely to face similar calls for additional funding. Schools should have enough money to improve performance but for other priority areas, such as the NHS, the money committed by government will probably only be enough to maintain standards. It will not allow improvements in access or expansion of services.

Funding for additional officers will relieve pressure on the police, but little thought has been given by government to the impact this will have on other parts of the criminal justice system. Prisons will struggle. Levels of violence and self-harm have grown rapidly, despite increased funding since 2016/17, and government policies, by increasing the prison population, will create a hole in the prison budget.

Boris Johnson also owns responsibility for fixing adult social care. But the amount his government has pledged will not even be enough to maintain existing services, never mind return access to 2010 levels or protect families against the potentially catastrophic costs of care.

The government’s ambitious infrastructure and investment plans will require departmental resources

Since 2010, the main way that government has made savings has been through holding down public sector pay. With recruitment and retention problems across the public sector, and commitments to above inflation increases to pay and the National Living Wage, there seems little prospect that such an approach can be employed successfully over the coming five years.

The government has reportedly recognised this, and is instead said to be determined to do away with a range of programmes, projects and quangos which were launched under previous administrations – including the Theresa May government.

However, in parallel with these targeted departmental savings, the government is also intent on delivering on ambitious infrastructure and investment plans. Projects like these are likely to require an increase in Whitehall’s capacity. As a forthcoming IfG paper will argue, government staffing levels have contributed to consistent underspending of capital budgets.

All this is without considering the impact of Brexit on public finances. Most studies find that Brexit will reduce economic growth. This, in turn, will impact on tax receipts and the amount of money the government can spend on its priorities.

As difficult as 5% cuts may be, far more may be needed to balance the books.

- Supporting document

- performance-tracker-2019.pdf (PDF, 4.23 MB)

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Spending review

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government