Civil service cuts will force ministers to choose between painful options

A crude approach to cutting jobs will lead to false economies and a less efficient civil service

With the prime minister signing off a new target to reduce the civil service to its pre-Brexit headcount by 2025, Rhys Clyne argues that a crude approach to cutting jobs will lead to false economies and a less efficient civil service

The government is aiming to cut 91,000 civil service jobs, with ministers and permanent secretaries asked to draw up detailed plans for their departments. The government's seriousness about reducing the civil service by nearly a quarter, with the aim of saving £3.5bn, can only be judged once those plans have been submitted, but ministers should start with one certainty: 91,000 jobs will not be cut by painless-sounding efficiencies to back office staff alone.

The government and its responsibilities have changed a lot since 2016

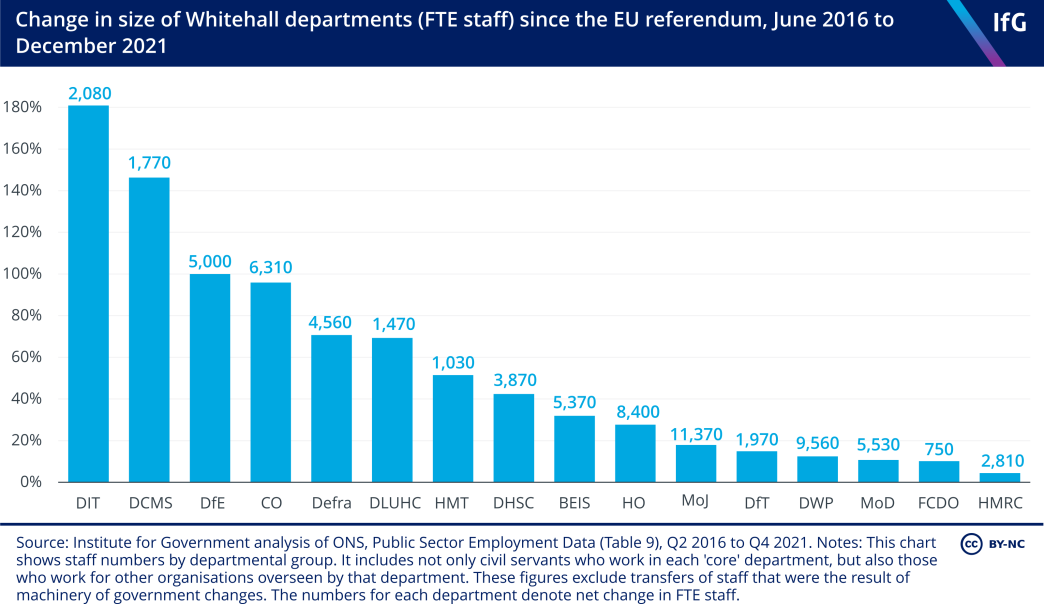

Ministers have chosen the pre-Brexit headcount of around 384,000 staff as the benchmark of efficiency to which the civil service should return. It has grown by 91,000 people since then, an increase of 24%. But when deciding where to cut, ministers should recognise that the government has changed significantly and permanently in the years since 2016.

The British government now has new post-Brexit responsibilities that cannot be dropped. The Department of International Trade and its 3,200 staff will still be needed. The Home Office has added 8,400 officials, some of whom are helping to administer the new immigration system, processing visas from the EU for the first time. Defra and BEIS have each grown by around 5,000 staff, adapting to the regulatory and policy roles inherited from the EU.

Many of the roles created to support the UK’s negotiations with the EU prior to the UK’s departure will no longer be needed. And the resource-intensive “no deal” work has ended. But in practice most of these officials have since transferred to new roles, including supporting the UK’s response to Covid. On the pandemic, too, there will be scope for removing jobs created to bolster the government’s emergency response. The Department of Health and Social Care has grown by 40%, and some of these new roles will not be needed in the future. But the government should not forget the lessons of Covid. It will need staff to monitor and prepare for future pandemics and similar critical risks if the UK is to be better prepared in future, as well as to tackle the huge legacy of backlogs in public services.

Headcount is only one part of the efficiency puzzle. The civil service should be the smallest it can be while being able to implement the government’s priorities. Given the government’s post-Brexit responsibilities and the scale of the crises facing the country, from the climate to the cost of living, there is no clear reason to assume 2016 is the right benchmark. Nor is the 2016 number the ‘default’ size of the civil service. As departments set about planning to meet this target, ministers need to justify the size of the workforce in its own terms.

Frontline staff and those with valuable back-office skills will be among the 91,000 cuts

Last year the government set the aim of reducing the civil service to its pre-Covid headcount while protecting frontline roles. Half of all civil servants work on the frontline delivering services to the public, many in job centres, prisons and for HMRC. So this would have meant removing anywhere between 28,000-57,000 jobs depending how the government defined “frontline”.

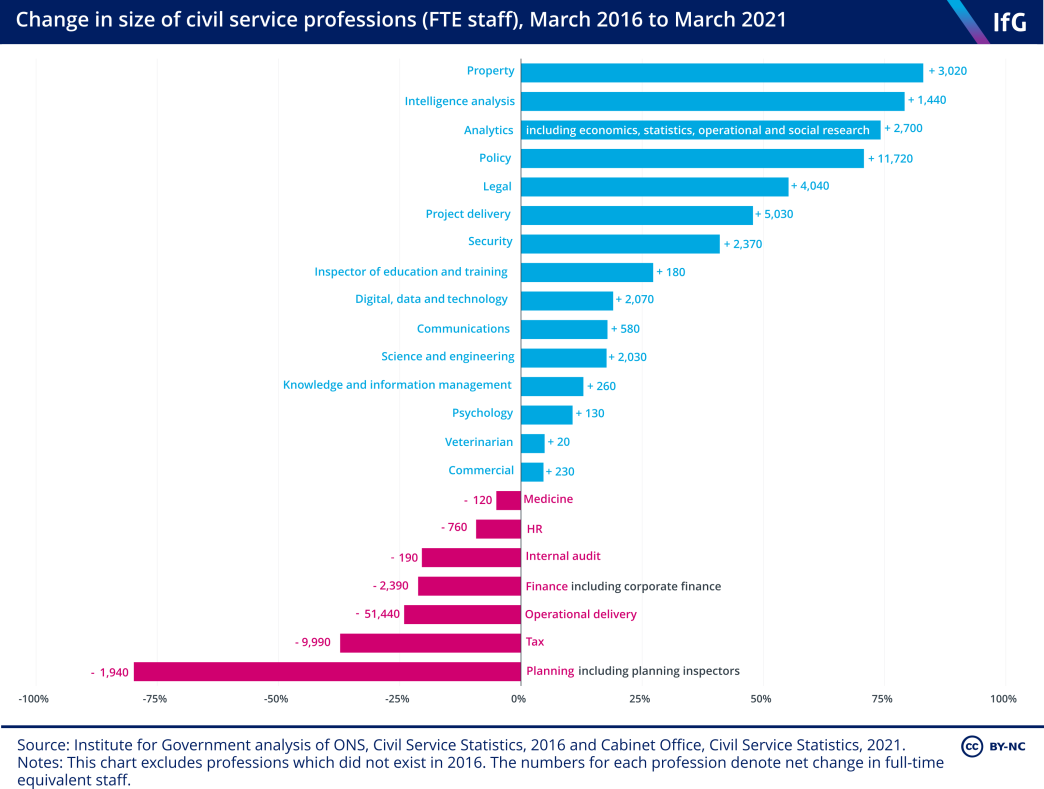

The new target of 91,000 roles in the next three years is a deeper cut that will not be achieved without losing frontline roles and other skills the government itself has said it wants to prioritise. There were nearly 12,000 more staff working on policy in 2021 than there were in 2016. There is certainly scope to remove some policy officials, whose numbers have grown by over 70% since 2016. But not all of these roles are expendable, and the total number of policy experts in government – roughly 30,000 – is dwarfed by the 91,000 target. In fact, if the government were to protect jobs in the departments with the most frontline services – DWP, MoJ, HMRC, MoD and the Home Office – it would have to scrap the ten smallest, policy-focused departments entirely to meet its target, leaving only BEIS standing.

That is of course absurd, but it demonstrates the difficulty ministers and senior officials will have meeting this target without undermining the government’s delivery capability. They will have to make cuts in frontline roles, and they will have to include other back-office functions the government would like to strengthen, such as science and engineering, digital, commercial and project delivery.

Detailed workforce plans are needed, not blunt tools such as blanket recruitment freezes

As we argued last October, poorly targeted cuts are an inefficient way to manage the civil service and risk undermining the government’s ability to achieve its priorities. It has been suggested that the government will meet this target with a blanket recruitment freeze. Tools like this are sometimes needed but they do not discriminate effectively between expendable jobs and those important to the government’s priorities. They also tend to result in talented, mobile employees leaving the civil service more quickly to progress their careers, not a recipe for efficiency.

The target of £3.5bn in savings will only realised if new costs are not created elsewhere through the need to hire consultants or the risk of expensive mistakes in public services. The cuts will need to be precisely targeted within teams to avoid undermining the government’s delivery capability, where possible. And they will need to take account of departments’ plans to recruit officials to new sites outside London.

This will only happen if senior officials have the time and opportunity to develop detailed, team-by-team workforce plans for their departments. They will need to map the resources of the workforce against the priorities of the government and the skills required to achieve them. If efficiency is the aim, these plans are a crucial next step. Too much focus on headline-grabbing numbers, rather than the work the government actually needs to do, will mean job cuts prove to be a false economy.

- Supporting document

- moving-out-civil-service-location.pdf (PDF, 841.91 KB)

- Topic

- Civil service

- Keywords

- Civil service reform

- Publisher

- Institute for Government