Electricity market

The price of natural gas continues to largely determine the price that consumers pay for electricity.

Why does the price of electricity in the UK depend so much on the price of gas?

In the UK, electricity is increasingly generated using renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, and the cost of generating it in this way has fallen sharply over recent decades. Despite this, the price of natural gas continues to largely determine the price that consumers pay for electricity. This explainer sets out why.

How is electricity generated in the UK?

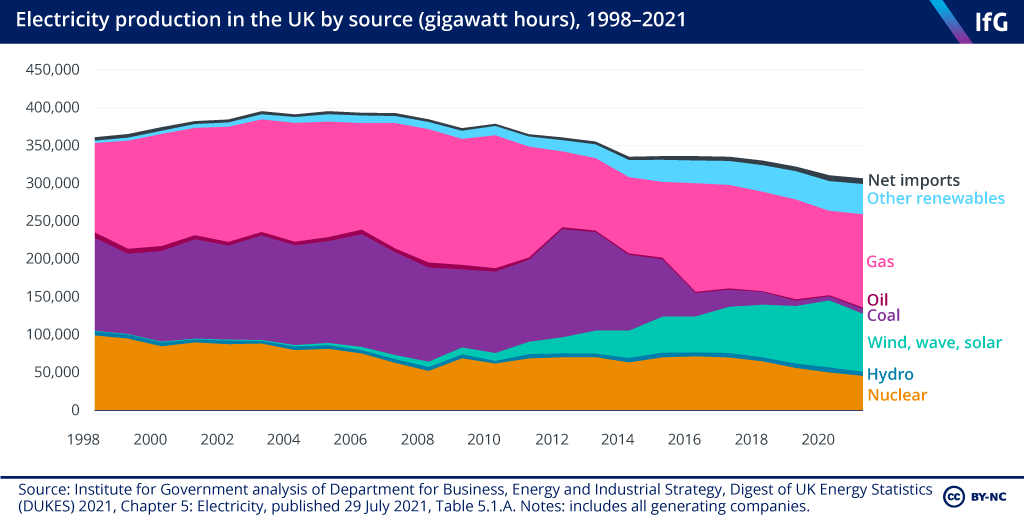

The UK uses a mix of sources to generate its electricity: fossil fuels (mainly gas and coal), nuclear energy and renewable energy. The contribution of different generation methods to overall electricity supply has changed dramatically in recent decades.

In 1990, coal generated 80% of electricity. Newly privatised electricity companies then shifted towards generating electricity using natural gas, which had become cheaper (as the production of gas in the North Sea increased) and more efficient (thanks to technological advances and, more recently, carbon pricing).

Since 2000, fossil fuels’ contribution to overall electricity supply has decreased, while nuclear energy has provided 15-25%. The share of renewable sources has increased sharply: having made only a marginal contribution to supply in 2000, in 2020 its contribution was higher than that from fossil fuels for the first time (though this reversed in 2021).

How is the electricity market structured?

For electricity to arrive in homes and businesses across the UK, it must be generated, transported and then sold to the customer. Companies can be involved in any or all three of these stages.

- Generation: There are many different companies operating in the electricity generation sector, of different sizes and using different generation methods.

- Networks: The National Grid runs the transportation (transmission and distribution) of electricity. It is responsible for making sure that the supply of electricity on the grid constantly meets demand.

- Retail supply: Electricity suppliers are responsible for selling electricity to consumers (households and businesses) and operate in a competitive market. There are many suppliers of different sizes and consumers can choose which one provides them with electricity.

How is the price of electricity determined?

There are two markets for electricity: the retail market (where households and businesses buy electricity from suppliers) and the wholesale market (where suppliers – and energy traders – buy electricity from generators).

Retail market

In the retail market, consumers enter into a contract with an electricity supplier.

Households typically either agree a fixed price or pay the ‘default tariff’. The industry regulator, Ofgem, sets a ‘price cap’, which determines the latter. Given the recent surge in wholesale prices and huge uncertainty surrounding future prices, most fixed-price deals are now above the price set by the price cap, so most customers entering into a new contract will pay the default tariff. Ofgem now adjusts the price cap four times a year and this is set using market-based forecasts for wholesale prices during the three months that it covers.*

Most businesses also buy energy from the retail market and will agree a contract with a supplier at a fixed price for a fixed period. But the price cap does not apply to businesses, so when such a contract comes to an end, the new price they face will depend on the current wholesale price. Businesses’ energy costs are therefore much more volatile than those for households.

Wholesale market

Electricity suppliers buy the electricity they need to supply homes and businesses from generators on the wholesale market, which is open and competitive.

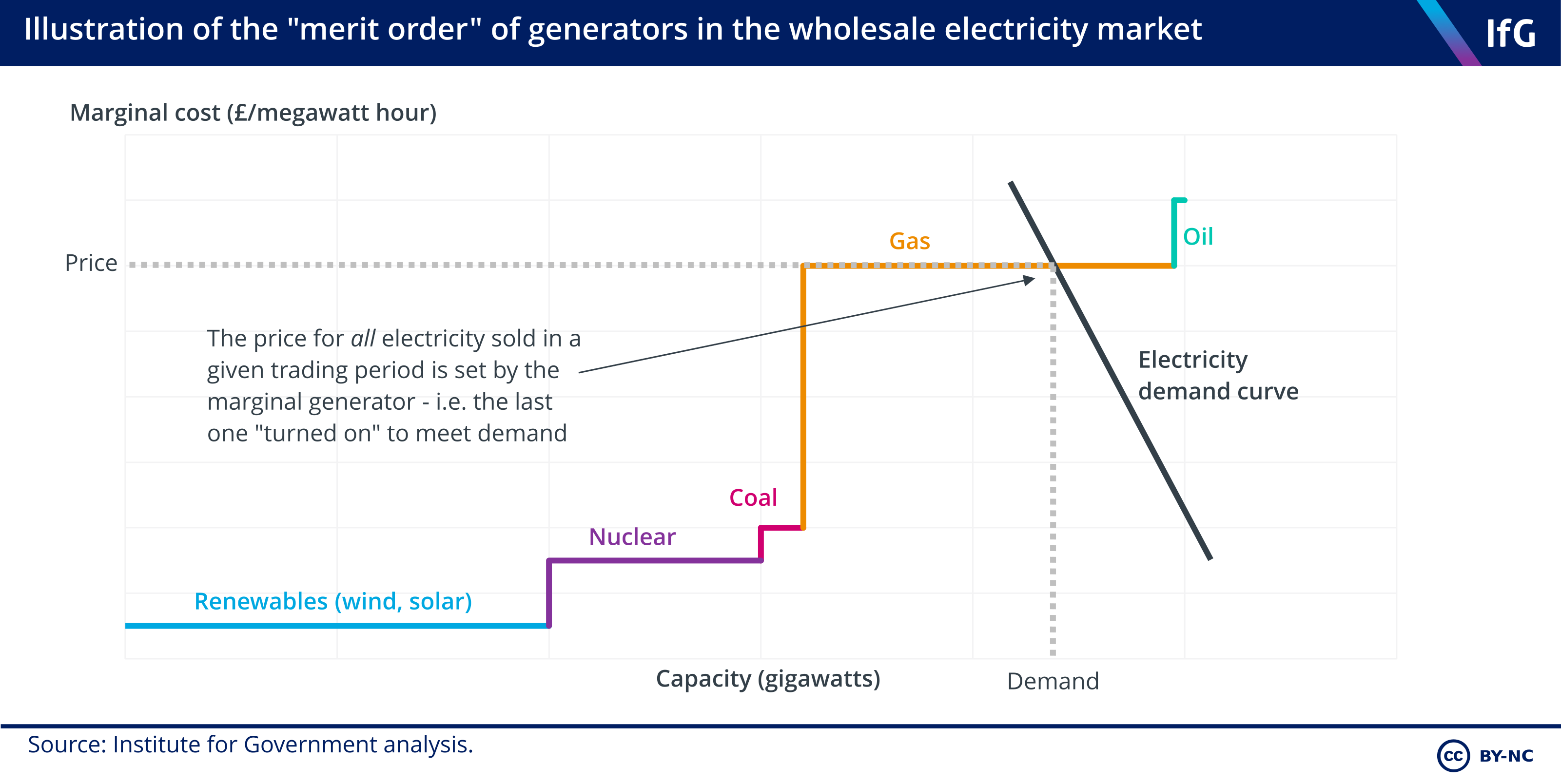

Wholesale electricity prices are not regulated and, instead, trading on spot (or day-ahead) markets sets them. In these markets, electricity generators bid to contribute to the power grid. The power exchange (Nord Pool in the UK) accepts these bids in price order, from lowest to highest, until demand is met, in what is known as the ‘merit order’: sources of electricity with the lowest marginal cost of generation (typically renewables, as they do not use any fuel) are the first bids to be accepted, and sources such as gas- and coal-fired power stations are the last (as they use fuel and the generator must also pay carbon tax on that fuel use).

In each half-hour trading period, the marginal cost of the last generating unit used to meet demand sets the price that the buyers (energy suppliers or traders) pay to the sellers (energy generators or traders) – known as a ‘pay as you clear’ model.

The marginal producer of electricity in the UK is most often gas because it is one of the most expensive sources, so is chosen last in the ‘merit order’ on the spot market. But it serves a vital role because gas-fired power stations can be easily switched on and off at short notice to make sure that supply balances to meet demand. Renewable energy sources, on the other hand, are unpredictable due to changes in weather, while nuclear energy provides a fairly constant source of power that is difficult to turn on and off.

This means that, although generation methods that have low marginal cost (including renewables and nuclear) produce the majority of UK electricity, the price that is paid for it in both wholesale and retail markets is set much higher, at the marginal cost of generating electricity with gas.

*The price cap includes costs other than wholesale prices, such as green levies and ‘network costs’, but these are much less volatile than wholesale prices.

How might the market be reformed?

It may seem odd that electricity produced with low-cost renewables should cost suppliers (and thus consumers) the same high price as electricity generated by gas-fired power stations. But this is a common feature of competitive auction markets of any kind.

The wholesale electricity market could instead be run using a ‘pay as bid’ auction model. In this type of auction, electricity generators would put in bids and be paid the price they bid, rather than the bid of the highest-priced supplier. If low-cost generators submitted bids at their marginal cost, this would lower the average cost in the wholesale market, feeding through to lower prices in the retail market.

But there would be no incentive for low-cost generators to bid at their true marginal cost. Instead, they would bid at the price at which they expected the market to clear. If renewable electricity generators were aware that demand was high enough for gas-fired power stations to be required, then they would know they would be able to sell their energy at (or just below) the marginal cost of gas-fired power stations. To prevent this sort of strategic bidding, additional controls on the market would be necessary.

Without radically altering the wholesale electricity market, it is difficult to break the link between marginal electricity generation costs (typically from gas) and the prices that consumers pay. But as part of its recently announced review of electricity market arrangements (REMA),[1] the government is considering making the sort of fundamental changes that could break the link. Some options being considered include:

- moving to the ‘pay as bid’ auction model – but without additional controls imposed by government this may not lead to particularly large changes in electricity prices

- splitting the electricity markets into separate markets for variable power (for example wind and solar) and constant power (such as nuclear) – a more radical option.[2]

- the creation of a ‘green power pool’, a government-backed entity that would offer long-term contracts to all low-carbon generators and sell directly to consumers, using exclusive access to cheap green power to deliver lower prices[3]

The “Energy Price Guarantee”[4] recently announced by the prime minister does not change of the rules of the market in order to lower prices, as the solutions above do. Rather, the policy lowers prices in the retail market by paying suppliers for the difference between the guaranteed price (equivalent to a typical household paying £2,500 per year) and the wholesale price, rather than changing the way in which wholesale prices are determined.

However, alongside the energy price guarantee, Truss announced that the government was exploring agreeing contracts with renewables generators (similar to existing ‘contracts for difference’) to provide electricity to the grid at below the current market price. The main benefit for generators would be price stability for the next 5-10 years. This would go some way to decoupling gas and electricity price, but is being considered as a short-/medium-term measure outside of the more fundamental reforms that may be introduced as a result of the REMA process.

1. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, ‘Review of electricity market arrangements’, GOV.UK, 2022, retrieved 8 September 2022, www.gov.uk/government/consultations/review-of-electricity-market-arrangements

2. Keay, M. and Robinson, D., Market design for a decarbonised electricity market: the “two market” approach, in Rossetto, N. (ed.), Design the Electricity Market(s) of the Future, proceedings from the Eurelectric-Florence School of Regulation Conference, 7 June 2017. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/market-design-for-a-decarbonised-electricity-market-the-two-market-approach/

3. Aldersgate Group, Policy Briefing: Delivering competitive industrial electricity prices in an era of transition, Aldersgate Group, 2021, www.aldersgategroup.org.uk/content/uploads/2022/03/DELIVERING-COMPETITIVE-INDUSTRIAL-ELECTRICITY-PRICES-IN-AN-ERA-OF-TRANSITION-policy-briefing.pdf

4. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, ‘Energy bills support factsheet: 8 September 2022’, GOV.UK, 2022, retrieved 13 September 2022 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/energy-bills-support/energy-bills-support-factsheet-8-september-2022

- Topic

- Public finances

- Publisher

- Institute for Government