Preparing a shadow ministerial team for office: Lessons from 1997 and 2010

What the last two changes of government tell us about effective transitions.

Summary

In the UK the main party of government has changed only twice in three decades. In 1997, Labour took over after 18 years of Conservative rule; in 2010, after 13 years of Labour, the Conservatives again became the largest party, entering a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. The next general election, expected in 2024, will mark 14 years of Conservative or Conservative-led government; current opinion polls suggest government may change hands again.

The Institute for Government is undertaking research in preparation for the expected 2024 election and all its potential outcomes, including looking at how the opposition and the civil service should prepare for a possible transition of government.

Among the many competing demands on any leader of the opposition is to create a strong shadow ministerial team capable of an effective transition – and then, crucially, of effective government. The timing of any reshuffles to achieve this aim is important. This Insight looks at the pattern of reshuffles around the 1997 and 2010 elections, the ministerial and shadow experience of those eventually appointed in those new governments, and what impact this had on their work as ministers.

Drawing on the Institute for Government’s data analysis, reports and Ministers Reflect archive, we identify lessons for how Sir Keir Starmer should approach building his shadow ministerial team before a 2024 general election. In particular, we look at how Starmer should time and approach a potential reshuffle, now mooted to take place in the autumn, to increase the effectiveness of his shadow team if they enter government.

The Institute for Government has published several reports showing that ministerial churn is detrimental to government effectiveness. It:

- hinders effective policy making

- prevents long-term thinking

- undermines relationships ministers have worked hard to establish

- inhibits parliamentary scrutiny

- can mean government resources must be redirected with little notice. 26 Sasse T, Durrant T, Norris E and Zodgekar K, Government Reshuffles: The case for keeping ministers in post more longer, Institute for Government, 2020, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/government-reshuffles-case-keeping-ministers-post-longer

Many of these problems apply in opposition, too. Relationships with other shadows and with outside actors are disrupted by shadow ministerial turnover, as, crucially, is opposition policy development. Unlike ministerial experience, which cannot be developed in opposition, amassing policy making experience is valuable. Shadow ministers will find they are at an advantage if they enter government with a well-developed plan, for the brief they are given.

There are some good reasons for moving shadow ministers close to elections, as well as in the government formation process. Political parties are focused first and foremost on winning general elections, and this requires different skills to running a department. There are always cases where reshuffles may be required to reward loyalty, or promote a potential rising star. Shadow ministerial teams may also require a fresh set of eyes in a policy area that isn’t working, to improve difficult relationships between shadow ministers, or simply to replace poor performers. New governments are never exact facsimiles of the shadow frontbench. But just as effective government is damaged by churn, opposition party leaders should also aim to keep such moves to a minimum.

Reshuffles held close to a general election can hinder good government

Having shadowed a role allows a new minister to get on top of their brief more quickly, to establish a good rapport with ministers holding related briefs (with whom they ideally will have shadowed), and to develop and stress-test the policies they want to pursue in government in greater detail, increasing their chances of success in government. Michael Gove’s education reforms, for example, were largely developed during his three years shadowing the schools brief. 29 Riddell P and Haddon C, Transitions: Lessons learned: Reflections on the 2010 UK general election – and looking ahead to 2015, Institute for Government, 2011, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/transitions-lessons-learned This allowed for relatively quick implementation – his 2010 schools white paper was published six months after the coalition government entered office.

The benefits of continuity mean that reshuffles close to a general election can be counter-productive and can destabilise policy development. Shadow ministers rightly seek to put their stamp on policy, meaning that existing work is lost if moves are made immediately before or after a general election –reshuffles in both 1996 and 2009 demonstrated that shadows moving role in the year before an election have their work cut out to make an impact. Opposition leaders should avoid making major changes to shadow ministerial teams in the 12 months before an expected general election. A Labour reshuffle taking place now, with an election expected in spring or autumn 2024, would already be relatively late. So if the current leader of the opposition wants to make any changes to his team he should do so sooner rather than later.

Reshuffle moves should reflect the planned structure of government

Should a leader of the opposition decide on a reshuffle close to an election, they should focus on preparing the shadow ministerial team for government – specifically the shape that government will take. Previous Institute for Government research has shown that ‘machinery of government’ changes – creating new departments – can be expensive in terms of lost momentum and productivity and should only be carried out with considerable planning. 30 Durrant T and Tetlow G, Creating and Dismantling Government Departments: How to handle machinery of government changes well, Institute for Government, 2019, retrieved 28 April 2023, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/creating-dismantling-government-departments

The lesson of the short-lived Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, created by Tony Blair immediately post-election to appease John Prescott, should caution any opposition leader against ill-thought-through departmental reorganisations made to keep shadow ministers happy, rather than as part of a more thoughtful plan for the shape of government. To avoid this, opposition leaders should ensure that their shadow ministerial appointments mirror the planned machinery of government by default.

Leaders must carefully balance politics and effectiveness in reshuffles

There can be good political reasons why opposition leaders might appoint someone to the shadow frontbench – but their potential effectiveness as a minister is not always top of the list. Having campaigners in senior roles can be important to opposition leaders, particularly when winning a general election is their first priority. But a shadow cabinet with an abundance of political operators at the expense of potentially good ministers can lead to post-election difficulties.

Opposition leaders should prioritise ministerial quality when appointing their final pre-election shadow cabinet, delicately balancing this with the demands of campaigning and party management. This may mean appointing ‘campaigner’ shadow ministers to senior posts which are not responsible for significant opposition policy development or for running a large department post-election – Cabinet Office and party roles can offer useful spaces for this, as they did in 2010.

Finally, opposition leaders should think about two different types of experience when assembling their team: policy experience and ministerial experience. While policy experience can be built in opposition – for example by shadowing the department or chairing a relevant select committee – the ministerial experience available to a leader is already determined (and reduces the longer a party is in opposition). Leaders should think carefully about how to use this resource, and aim to avoid giving any major ministerial jobs to people who have neither a background in their policy area nor a good understanding of the job of being a minister.

The transition to government: 1997

Key shadow ministers were in place for at least three years before the election

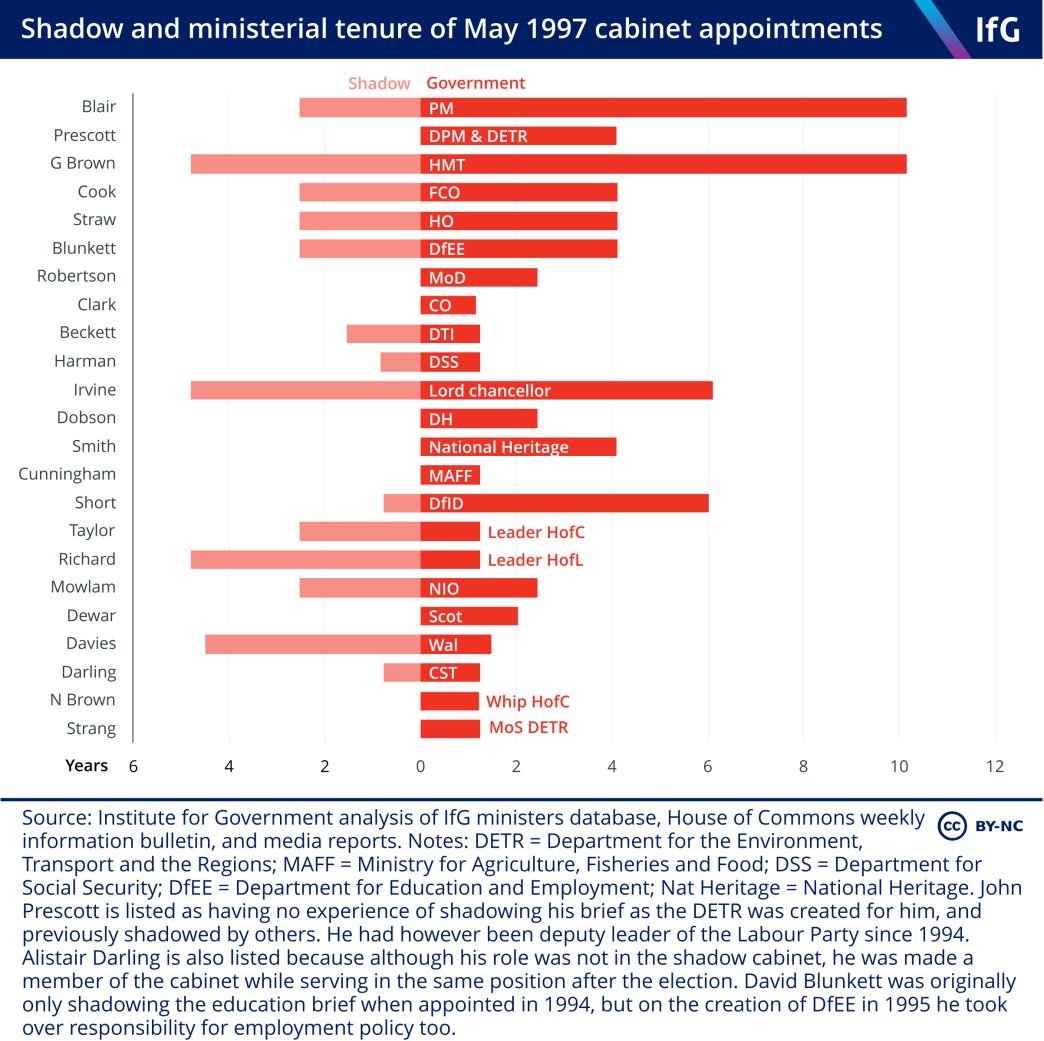

The pre-1997 shadow cabinet was affected by shadow cabinet elections – a since dropped Labour policy that saw MPs elect some shadow cabinet members – which limited the leader’s role in choosing frontbenchers. Six members of Tony Blair’s first cabinet were appointed or elected when he became Labour leader in 1994, but four had been in their shadow roles since 1992, when Blair’s predecessor John Smith was leader.

Gordon Brown was the most prominent shadow cabinet member to keep his job from 1992 onwards, but the other great offices of state, along with the deputy leader role, were filled in October 1994 when Blair assembled his first shadow cabinet. Along with Brown, Robin Cook as foreign secretary, Jack Straw as home secretary, John Prescott as deputy prime minister and David Blunkett as education and employment secretary (a key New Labour priority) had all shadowed their briefs for at least three years in the run-up to the election, and then kept their roles for the whole of the 1997–2001 parliament.

These senior shadow cabinet members all benefited from the opportunity to work on policy in opposition. This included meeting senior civil servants in their future departments to discuss their plans for government as part of ‘access talks’ between opposition politicians and civil servants, permitted by John Major from January 1996, 16 months before the 1997 general election. They also had the opportunity to build other relationships in their policy area. For instance, David Blunkett met with Sir Michael Bichard, the permanent secretary at the Department for Education and Employment, every six weeks from the summer of 1996 onwards, as well as meeting his future principal private secretary and the department’s management board. This gave Blunkett the opportunity to explain his plans for the department in advance, and the department time to prepare for his arrival. Michael Barber, chief education adviser to Blunkett, later said this contact was crucial in helping the department implement Blunkett’s policies quickly and effectively. 32 Barber M, Instruction to Deliver: Tony Blair, the public services and the challenge of achieving targets, Politico’s, 2007, p. 29.

Similarly, Jack Straw told the Institute for Government that his time as shadow was very helpful once he became a minister:

“For the three years before [the election] I was Shadow Home Secretary; we had worked incessantly and very thoroughly on a whole range of reforms that I wanted to introduce... We’d stress-tested the material and the officials in the Home Office had had this material for at least six months. So I knew what I wanted to do.”

There was also some longevity in Labour’s territorial office shadows, which would play a crucial role in driving through New Labour’s devolution agenda and most notably supporting the peace process in Northern Ireland. Mo Mowlam shadowed the complex Northern Ireland brief for more than two years before taking the role in government, and leading the UK government’s input into the negotiations that led to the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement.

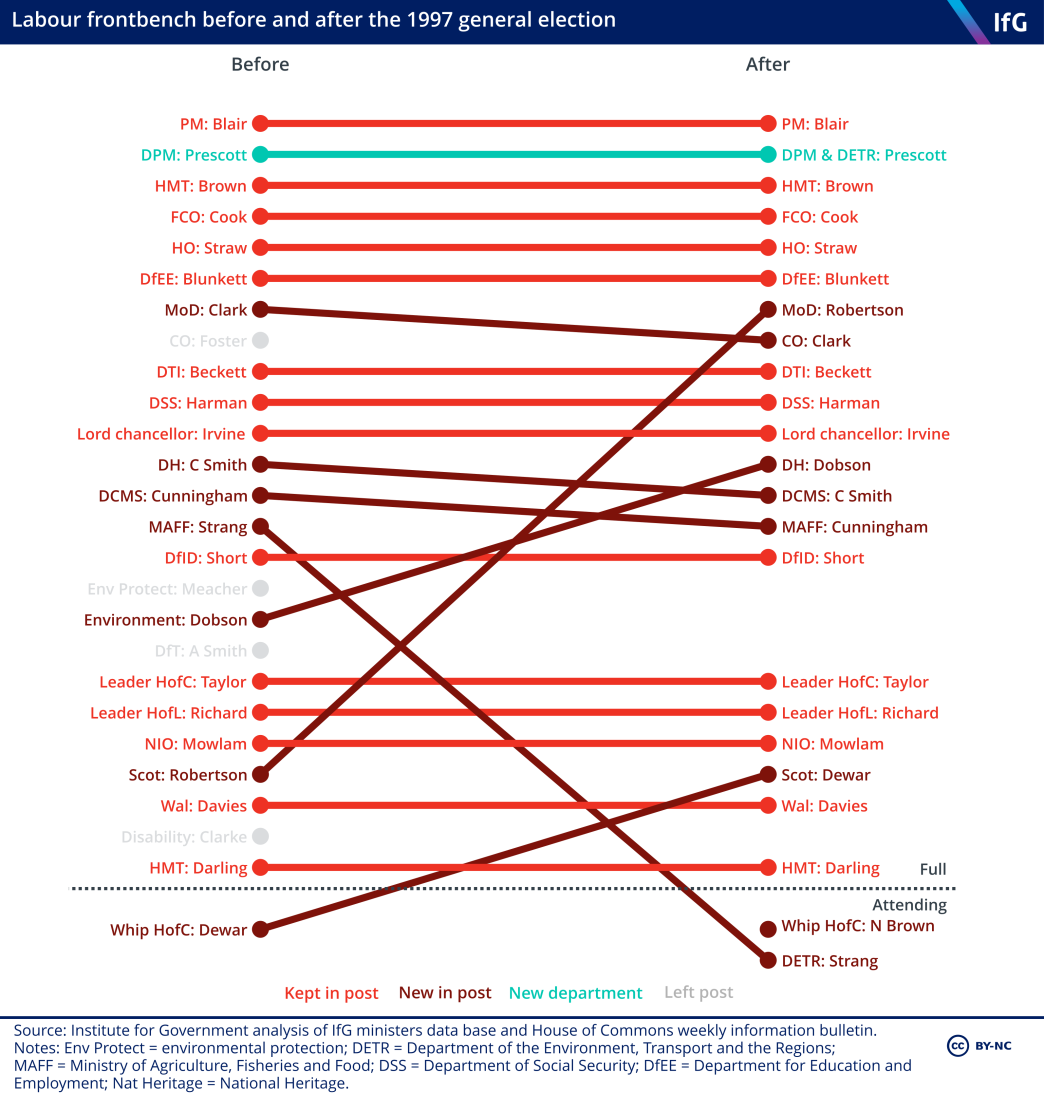

But the rest of the ministerial team changed a lot around the election

Despite these successes, Blair’s transition was also marked by a significant amount of discontinuity, resulting from both the political need to find big jobs for key names, and the lack of forethought about some key portfolios. The remainder of Blair’s shadow ministerial team was largely constructed after 1994. Reshuffles in 1995 and again in 1996 gave Margaret Beckett, Harriet Harman and Clare Short the portfolios they would take into government, as well as giving Alistair Darling the shadow chief secretary to the treasury role. But many of the other changes that were made in these reshuffles were not carried through to government.

Some key briefs, including health and transport, changed at every reshuffle from 1994 to the formation of government in 1997. This was mentioned by Alan Milburn, minister of state for health in 1997 and later a cabinet minister, as a key reason for early problems Labour had in the Department of Health:

“It’s no coincidence that the two areas of public policy when New Labour hit the ground running were economic policy and education policy. Why? Because there was continuity in personnel… That didn’t happen with health. We had a different guy, Chris Smith, who was the shadow health secretary, and then Frank Dobson became the actual health secretary. Changing personnel… is a curse in modern politics.” 37 Rentoul J, ‘Alan Milburn’s message of “health choices for the many not the few” is still powerful’, The Independent, 15 April 2023, retrieved 25 April 2023, www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/labour-health-streeting-milburn-blair-b2319056.html

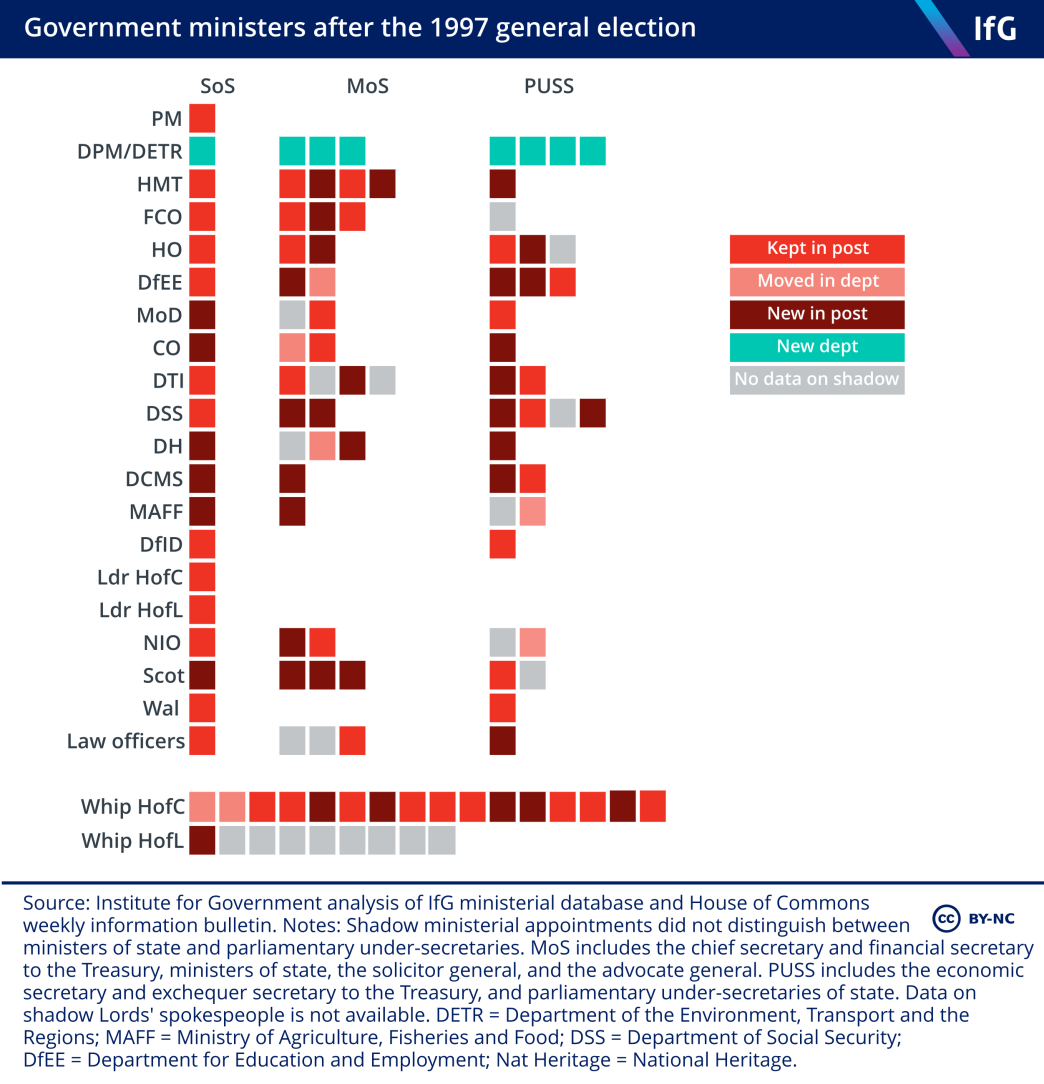

In total, nine full or attending cabinet ministers were appointed to roles they had not previously shadowed, including in the Cabinet Office, Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF), as well as chief whips in both houses. Junior ministerial moves were even more widespread – many departments, including the Scottish Office, MAFF and the Department of Health, were left with just one junior minister who had been shadowing the department. Despite this level of churn, most ministers did have some shadow experience even if not in the relevant department. The only member of Blair’s first cabinet who had not previously been in the shadow cabinet in some capacity was Nick Brown, who was promoted from deputy chief whip to chief whip and so was already well acquainted with his new role.

The level of churn on entering government was partly due to shadow cabinet elections, which obliged Blair to give shadow cabinet roles to MPs like Gavin Strang, Michael Meacher and Tom Clarke who were not necessarily natural allies. All were demoted when Blair entered government. This is not a problem facing Sir Keir Starmer – the Labour Party abolished shadow cabinet elections in 2011.

But some of the churn post-1997 might have been avoided with better planning in opposition. Blair’s shadow cabinet included posts which were duplicative, like shadow ministers for the environment and for environmental protection, both in cabinet. Some roles that existed in opposition were not carried over into government, such as the shadow cabinet role of minister for disabled persons’ rights. All the occupants of these briefs had to be given new roles, making the number of moves in the government formation process greater than might have been needed. And Blair also gave Harriet Harman and Frank Field roles as secretary and minister of state respectively in the Department of Social Security, a personality clash which ended in briefing wars between them, and the sack for both a year later 38 Mulholland H, ‘Frank Field buries the hatchet with Harriet Harman in dig at Brown’, The Guardian, 19 August 2009, retrieved 28 April 2023, www.theguardian.com/politics/2009/aug/19/frank-field-praises-harriet-harman – a problem which could have been foreseen, or at least tested out in opposition.

The creation of the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR) also made things more complicated. In opposition, John Prescott’s role was deputy leader of the Labour Party, but on entering government, to accompany his role as deputy prime minister he was made secretary of state at the new DETR. The need to give Prescott a bigger role led to the somewhat ill-judged creation of the new department, which combined functions from multiple previous departments.

Whatever the merits of the change, it did not help smooth the transition: despite shadowing various portfolios in opposition, Prescott had not worked on any relating to the DETR immediately pre-election, which had instead been shadowed by three other shadow cabinet members. Blair did let senior civil servants and some in his team know the change was planned, but the decision not to announce it publicly before the election led to the farcical situation of Sir Andrew Turnbull, then permanent secretary at the environment department, having to meet Prescott for pre-election talks away from London so that Frank Dobson, then officially still the shadow environment secretary, would not be aware. 39 Riddell P and Haddon C, Transitions: Preparing for changes of government, Institute for Government, 2009, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/transitions It is right that Prescott had some pre-election contact with the relevant civil servants but the situation could have been managed better without the unnecessary secrecy.

One of the shadow ministers for what became the DETR – Michael Meacher, who became minister of state for the environment under Prescott – did stay on in the department in a more junior role. But overall, the effectiveness of the ministers appointed in the department, the ability of civil servants working on transport and environmental issues and the stability of the whole ministerial team were undermined by the fact that the creation of the DETR was not properly planned for or announced in advance. As a result, Prescott’s performance was subject to repeated criticism, including by cabinet colleagues who accused him of failing to delegate decisions enough in the mega-department. By 1999 Blair was busy working out how to dissolve the department. 40 Grice A, ‘Crisis? What crisis? says Prescott as he jets off’, The Independent, 3 December 1999, retrieved 25 April 2023, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/crisis-what-crisis-says-prescott-as-he-jets-off-1126848.html

In short, many of those arriving as ministers in Blair’s government not only had no experience as a minister (just two had ever been junior ministers previously, in the 1970s), but also had limited understanding of policy areas they were expected to cover. In total, of the ministers for whom we have data (and excluding the DETR, which was a new department), approaching half (43%) had not been shadowing the department to which they were appointed in the run-up to the election. Many junior ministers, in particular, were given new briefs on entering government, which meant they had limited relevant policy experience.

Blair’s approach was criticised many years later by Harriet Harman, one of those who was given a relatively short period to shadow her role before entering government, and who lasted less than a year in her first ministerial job.

“I think the Leader of the Opposition should decide in advance – it doesn’t have to be years in advance – who will be the Cabinet ministers, to enable them to prepare properly, rather than have a big surprise.”

Ministers without shadow experience found things difficult – and moved on more quickly

As shown in Figure 1, there appears to be a correlation between how long a minister had shadowed a role and how long they lasted once appointed to it. Many of those appointed to a new cabinet role on entering government were on their way out by Blair’s first reshuffle in July 1998, including Strang, Clark, Cunningham and Nick Brown. Many of those appointed in 1996 were also moved or removed, including Darling, Harman and Margaret Beckett. By contrast, the 1994 or 1992 appointees like Straw and Blunkett lasted longer.

The competence, and experience, of Blair’s first cabinet also appear to have contributed to his decision to shuffle his team just a year into government. None of his cabinet had ever sat around the cabinet table before and of those leading departments just two – Cunningham and Beckett – had even been junior ministers. Blair appears to have seen his early reshuffle as a chance to change his team based on who was performing well in their new ministerial roles – something he was right to do, considering he had little evidence pre-election of how many of his team would perform. This was how he cast the demotions of Frank Dobson and Gavin Strang, for instance, who both left government in 1998 after struggling in their new roles, and in Dobson’s case clashing with the civil service. 42 Riddell P and Haddon C, Transitions: Preparing for changes of government, Institute for Government, 2009, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/transitions

Undoubtedly Blair’s own inexperience in government – he had also never been a minister at any level – played a part in his judgment about what was needed to run departments well. But greater continuity from opposition to government, or better planning in advance of government formation, could have made a difference. Some moves, including combining Harman and Field in the Department of Social Security, were seen as risky at the time. These sorts of personality clashes in government could have been avoided if ministerial teams had been properly tested out in opposition.

The transition to government: 2010

Key Conservative shadow ministers were in place from 2007 – some earlier

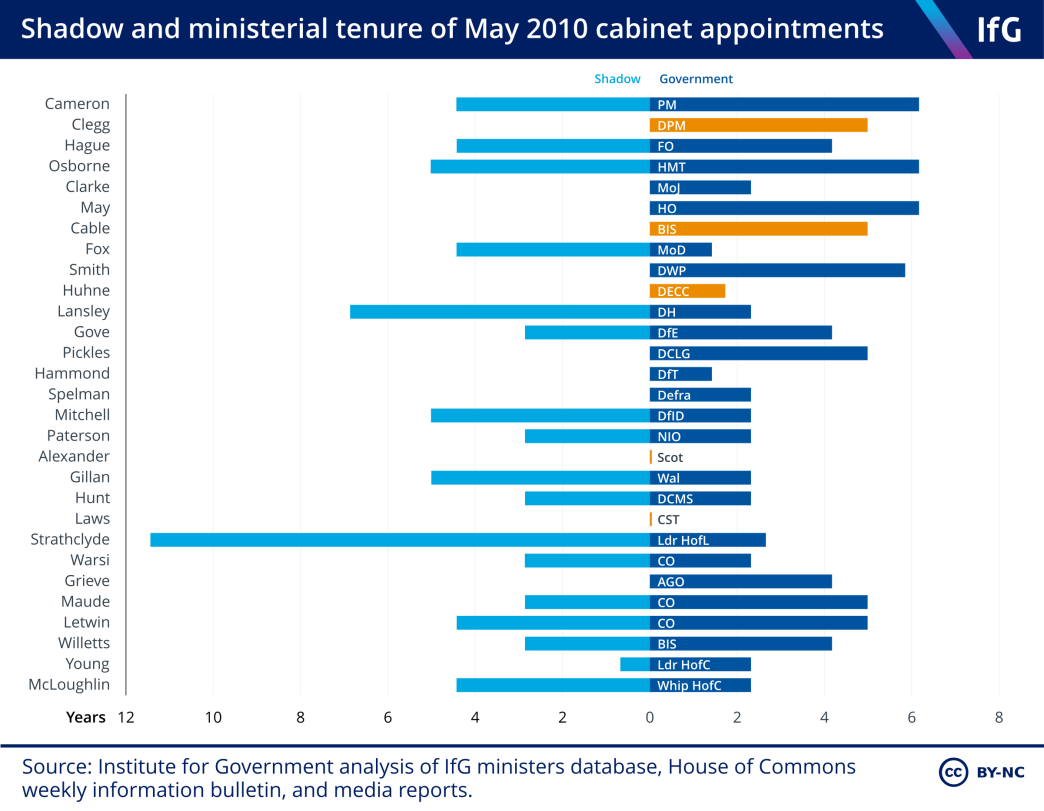

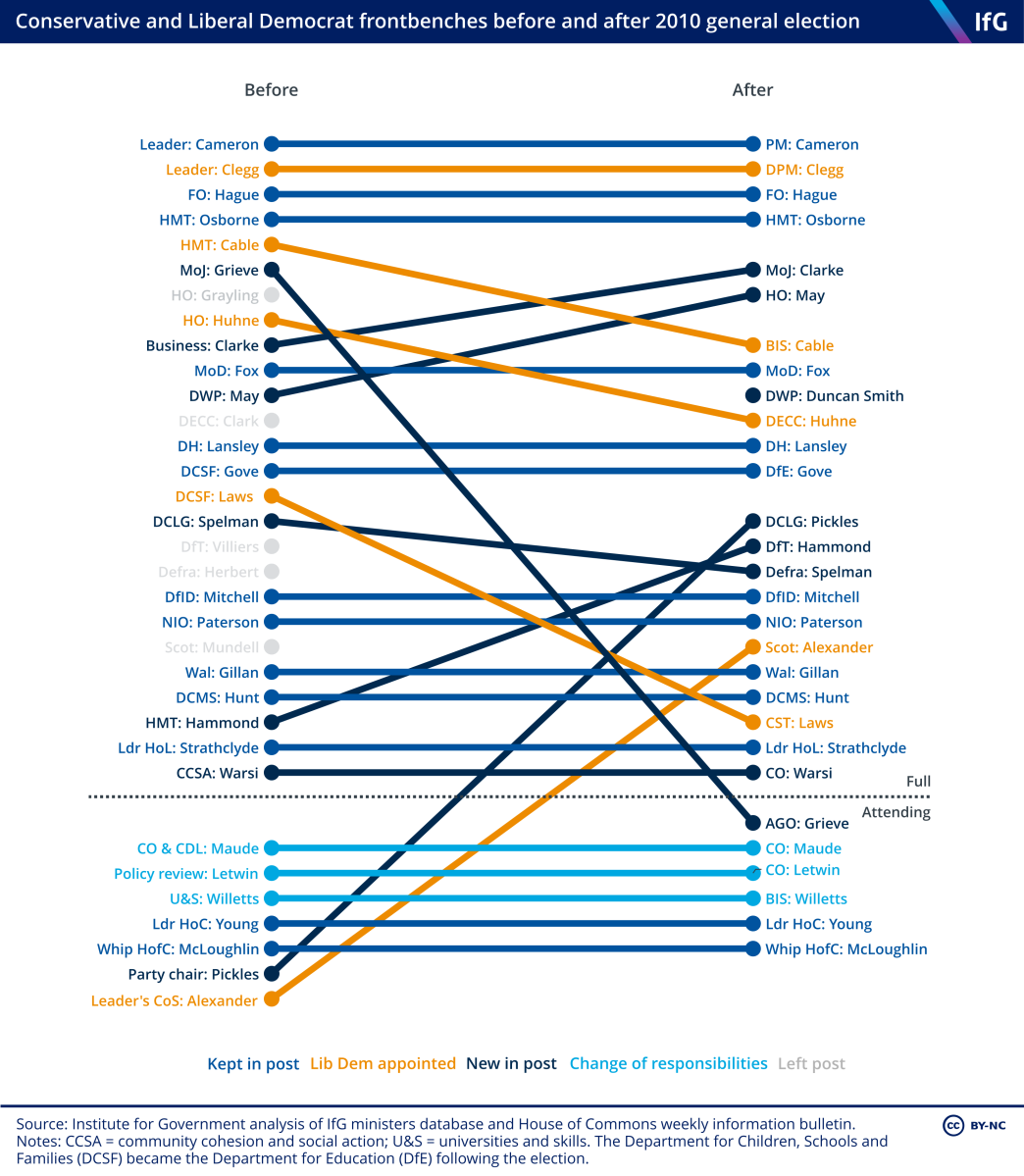

The appointment of ministers after the 2010 election was affected by the formation of a coalition government, which necessitated the inclusion of Liberal Democrat ministers. Despite this, some of the key Conservative ministers in David Cameron’s first cabinet had been appointed as shadows to their briefs as early as 2005, when he became party leader; George Osborne, who would become a key architect of the Cameron government, had been appointed six months earlier. These ministers were very well-acquainted with their departments and had strong visions for them by the time they entered office.

Cameron’s most significant reshuffle came a full three years before the 2010 general election, in 2007. Five ministers who would receive the cabinet posts they shadowed were appointed: Michael Gove was given the children, schools and families (later education) brief; Owen Paterson Northern Ireland; Jeremy Hunt culture; Francis Maude cabinet office; and David Willetts universities.

A final reshuffle took place in 2009, just over a year before the election. But no shadow cabinet minister appointed then went on to be appointed to their shadow post. Chris Grayling, for example, was promoted from shadow work and pensions secretary to shadow home secretary, but did not receive a cabinet job after the election. Instead he returned to the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), in a junior ministerial role. Theresa May was promoted from shadow leader of the Commons and women and equalities minister to shadow work and pensions secretary – but went on to receive the Home Office brief, which Grayling had shadowed, after the election. Several other changes took place in 2009, including Eric Pickles becoming Conservative Party chair, having previously served as shadow local government secretary, and former chancellor Ken Clarke being made shadow business secretary.

Most of these 2009 appointments received cabinet-level jobs following the election – but none received the post to which they were moved to shadow. Indeed, one cabinet-level change was reversed: Eric Pickles was returned to his old communities and local government brief.

On entering government, some ministers’ responsibilities were a natural evolution of their election-focused roles beforehand. For example, in opposition, Oliver Letwin served as shadow chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster and worked on the Conservative manifesto, while Francis Maude worked on preparation for government. Both did this opposition work as shadow Cabinet Office ministers and were given Cabinet Office jobs when the Conservatives entered government. Their government jobs were not exactly the same as their pre-election roles, but a natural progression of them: Letwin continued to develop government policy and worked on departmental business plans, while Maude was made responsible for civil service reform and a broad set of public sector and efficiency issues. These appointments demonstrate that election-focused roles can be repurposed in government, meaning such ministers do not need to be moved to departments with which they are unfamiliar.

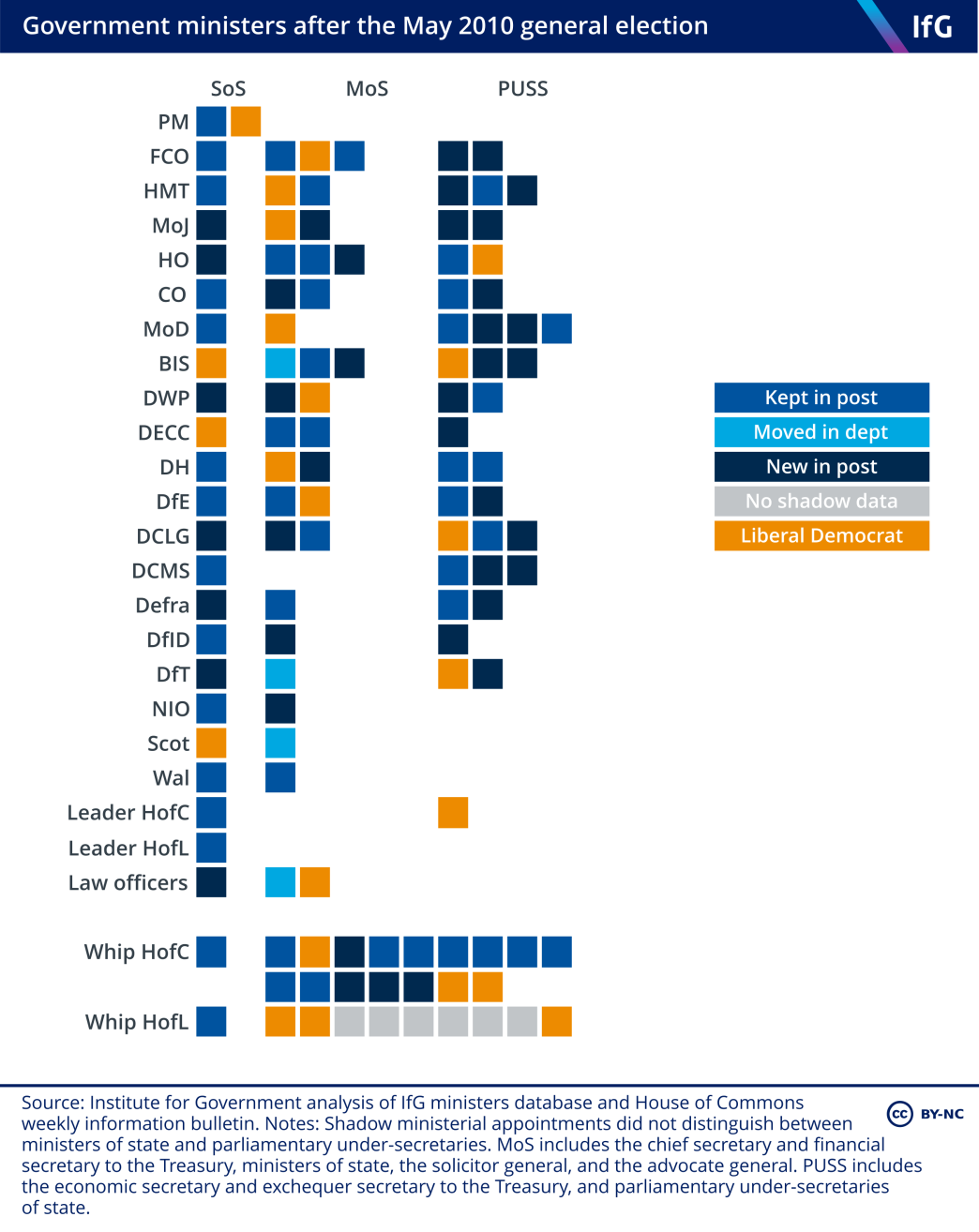

The coalition complicated ministerial moves

On entering government, most of Cameron’s first cabinet were appointed to roles they had been shadowing, or their close equivalent. Five Conservative ministers were appointed to cabinet posts different from those they had been shadowing, mostly since 2009: Philip Hammond, for example, was made transport secretary to make space for David Laws, a Liberal Democrat, to become chief secretary to the Treasury. Only one Conservative minister was brought into cabinet who had not shadowed any cabinet position immediately before entering government, former party leader Iain Duncan Smith. This relatively strong continuity between shadow and cabinet roles was achieved despite the inclusion of 23 Liberal Democrat ministers.

While the appointment of Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg as deputy prime minister did not directly ‘displace’ any Conservative ministers (Osborne deputised for Cameron in some key forums and William Hague was made first secretary of state, making up the ‘Quad’), the other three Liberal Democrats appointed to cabinet were given positions Conservatives shadowing these posts might otherwise have expected to receive. These were mostly from Cameron’s 2009 intake – Ken Clarke, for example, was shadow business secretary but was moved into justice – while longer-serving ministers were more likely to retain their posts.

This left Clarke’s department, the Ministry of Justice, with a ministerial team with no shadow justice experience (though Clarke himself had extensive experience elsewhere in government, as well as in the legal profession). Other departments were also left with only one minister who had shadowed the relevant policy area, including Iain Duncan Smith’s work and pensions department and Vince Cable’s business department.

Liberal Democrat ministers were typically appointed to posts junior to those which they had shadowed. Cable, for example, had been shadow chancellor and deputy leader but became business secretary; Chris Huhne had been shadow home affairs spokesperson (the party’s equivalent to shadow home secretary) and became energy secretary. Others who had shadowed secretary of state roles became junior ministers: the shadow work and pensions secretary, Steve Webb, for example, became a junior work and pensions minister. They did all, however, have substantial shadow ministerial experience, and cabinet ministers Cable, Huhne and Laws had all previously shadowed the briefs to which they were (in Laws’ case, very briefly) appointed.

Ministerial posts were unusually stable during the coalition – but some without shadow experience struggled

Unlike in 1997, there was no rapid post-election reshuffle (though the early resignation of David Laws led to two immediate ministerial moves). There were only two major reshuffles during the coalition’s five years in government, meaning that there was an unusual level of stability in ministerial ranks. The coalition agreement, which required a consistent number of Liberal Democrats in government, made it difficult to move ministers around without careful planning. Cameron was also said to hate reshuffles, believing that ministers should be allowed the maximum possible opportunity to get to know their departments. 46 Martin I, ‘David Cameron’s reluctant reshuffle’, The Telegraph, 1 September 2012, retrieved 28 April 2023, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/david-cameron/9513670/David-Camerons-reluctant-reshuffle.html

The relatively long shadow cabinet tenure of many Conservative ministers gave them policy experience that helped to compensate for a lack of direct government experience – Gove’s education reforms were a key example of this. Several of the Lords ministers appointed by Cameron also had policy experience across a range of portfolios, having served as opposition spokespeople for several departments concurrently. But inexperience remained a challenge to ministerial effectiveness: most (87%) ministers had never been in government before, with the notable exception of Ken Clarke, who had served as John Major’s chancellor and home secretary in the 1990s. Cameron’s health secretary Andrew Lansley told the Institute for Government that:

“In 2011, I think too many of the senior figures in our government had too little experience of what it is to be in government.”

This, and the fact that some senior ministers had not shadowed their briefs in opposition, led to some high-profile problems for the coalition government, of which the roll-out of Universal Credit was a prime example. This welfare reform was the brainchild of Iain Duncan Smith, a surprise appointment to the work and pensions department having not shadowed any ministerial post under Cameron’s leadership. Universal Credit had not appeared in the Conservative manifesto or the coalition agreement, and its implementation was plagued with difficulties. 47 Haddon C, Making Policy in Opposition: The development of Universal Credit, 2005-2010, Institute for Government, 2012, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/making-policy-opposition-development-universal-credit-2005-2010; Timmins N, Universal Credit: from disaster to recovery?, Institute for Government, 2016, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/universal-credit-disaster-recovery

Although Duncan Smith was familiar with the DWP’s policy area through his work at the think tank Centre for Social Justice, which he co-founded in 2004, he later told the Institute for Government that he found becoming a minister a big adjustment:

“I had never been really close to government. I was pretty much aware how government works, but nothing really prepares you for government till you actually do it.”

Other ministers who had shadowed cabinet positions other than those to which they were appointed found the transition perhaps less challenging – Theresa May, for example, acquainted herself with the Home Office brief quickly. 48 Riddell P and Haddon C, Transitions: Lessons learned: Reflections on the 2010 UK general election – and looking ahead to 2015, Institute for Government, 2011, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/transitions-lessons-learned

But even stability in opposition is not enough to drive success in government without the engagement of the party’s leadership and some flexibility, faced with the challenge of entering government – as Andrew Lansley’s controversial NHS reforms demonstrated. His plans for a large-scale restructuring of the NHS were made during his seven years shadowing the brief in opposition, with the help of a few advisers, and once in government he was not sufficiently flexible to adapt his plans based on civil service advice. Moreover, as the Institute for Government has previously written, the Conservative leadership was – due to their own lack of oversight – largely ignorant of the scale of such plans, which Lansley was forbidden from publicly discussing as the election campaign avoided a focus on the detail of NHS reform. Lansley was ultimately sacked from the health department at Cameron’s first reshuffle in 2012. Had Cameron exercised better oversight of his shadow ministers’ plans in opposition, the reforms’ challenges and Lansley’s demotion might have been avoided.

Conclusions

A key part of an effective opposition leader’s role in the lead-up to a general election is assembling a strong shadow ministerial team that is ready for government. The experience of 1997 and 2010 shows that stable shadow teams are more likely to result in effective governments. The stability of his team should be a priority for Sir Keir Starmer over the next year. He should, however, include contingency plans in case changes are forced upon him following a general election. A hung parliament, unexpected resignations or losses in marginal constituencies may make for a more complicated government formation process.

But if Starmer carries out a reshuffle in 2023, his priority should generally be to align shadow posts with government departments wherever possible, build the skills and experience of his shadow team, and minimise churn in the run-up to the election to maximise the opportunities for pre-election contact with officials and policy preparation.

The opposition should avoid major reshuffles too close to an election

In a new government the ministers who get on top of the brief most quickly and are most effective are usually those acquainted with their brief in opposition. Shadowing a role gives ministers time to do policy development: working out which policies might work, developing relationships with the sector, thinking about the practicalities of how policy goals might be achieved and canvassing feedback on their plans.

More stability also provides the opportunity for more extensive professional development support on how to be a minister – including that provided by the Institute for Government to successive governments, which has been praised by ministers including the current education secretary. Access talks, which begin 6–18 months out from an election, give potential ministers time to meet senior civil servants, establish relationships and set out expectations of what might happen in government. It is particularly disruptive to change those ministers during this time, as both Blair and Cameron found with their post-election cabinet appointments.

The lesson for the Labour Party leadership is simple: avoid unnecessary change around an election, and give ministers several years shadowing the brief. Starmer should be cautious about making substantial moves at this point, and, if moves are forced upon him, should consider how best to mitigate the problems that can ensue. His reshuffles in 2021 should already have established the spine of his ministerial team.

But if he does intend to shuffle his team once more before the election, he should ensure these changes are made sooner rather than later – preferably before the autumn – so that new shadow ministers are given the best chance possible to get on top of their brief before the election.

Shadows should be aligned with government posts as a default

Starmer should also use any reshuffle this year to align his team to how he wants his government to look after the general election should Labour win. On this point, he should learn more from Cameron than Blair, who failed to line up his opposition team with government.

If Starmer is not intending to undo recent machinery of government changes which created – among others – the Department for Business and Trade and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, any shadow cabinet reshuffle must match his team up to the new departments, allowing shadow ministers to work on the portfolio they would actually receive in government. This also raises the question of his current shadow cabinet ministers for mental health and international development, which currently have no equivalent in government. There are many ways to signal priorities for a new government short of creating new departments, including creating ministerial roles working across more than one department, or giving attending cabinet status to a junior minister.

The leader of the opposition should have government in mind when assembling a shadow ministerial team

Labour has some ministerial experience on their frontbench. David Lammy and Yvette Cooper are among five shadow cabinet ministers to have served as ministers in the last Labour government, alongside Ed Miliband, who held the ministerial role he is now shadowing. There is also relevant select committee experience among shadow ministers, with Cooper and shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves having chaired relevant committees. And while Starmer himself has never been a minister, he will be familiar with the upper echelons of government from his time as director of public prosecutions.

If Labour succeeds in forming the next government, the pressures it will inherit will be massive. The next 12–18 months give a good opportunity for those on the frontbench to build their skills and understanding of government, including through policy discussions, professional development and pre-election contact with the civil service. Learning the lessons from 1997 and 2010 on the timing of reshuffles, the importance of shadow experience and the pitfalls of unnecessary departmental changes will help Sir Keir Starmer ensure that if elected his first ministerial team is up to the task.

- Topic

- Ministers

- Political party

- Labour

- Position

- Leader of the opposition

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Public figures

- Keir Starmer

- Publisher

- Institute for Government