Performance Tracker 2023: Prisons

Poor long-term planning means prison populations have exploded, with dire consequences for rehabilitation and prisoner safety.

The prison service is in crisis. Since mid-2021, the prison population has been increasing at a rapid rate that is becoming increasingly unsustainable. The population is far above the prison service’s level of decent accommodation, and continues to edge closer to the upper limit of what is feasible while maintaining prisoner safety. This comes despite increases in staff over this period and real-terms spending increases from the mid-2010s. And the problem may get worse, with the Ministry of Justice expecting the number of prisoners to increase three times faster than prison capacity, leaving the prison population substantially higher than even prisons’ maximum theoretical capacity. Concerns over prisons overflowing have recently led to a series of rapid policy changes, despite the fact that the problems they seek to address have been known about for years.

In the context of a booming prison population, workforce shortages combined with high levels of turnover and inexperience among existing staff are particularly concerning. These workforce problems have contributed to a situation in which, a year after Covid lockdown restrictions were formally lifted, some prisoners remain in their cells for up to 22 hours per day. This places severe limitations on prisoners’ access to rehabilitative activities and health services. Similarly, levels of violence, both between inmates and assaults on staff, fell sharply at the start of the pandemic but have since started rising again. And rates of self-harm in female prisons are 119% higher than on the eve of the pandemic.

While recent policy changes may take the pressure off prisons’ population growth, the government must find a long-term solution if it is to avoid a cycle of repeat crises. In the absence of such a solution, we can continue to expect dangerous conditions that harm prisoners, prison officers and the wider criminal justice system.

Spending on prisons fell in 2021/22

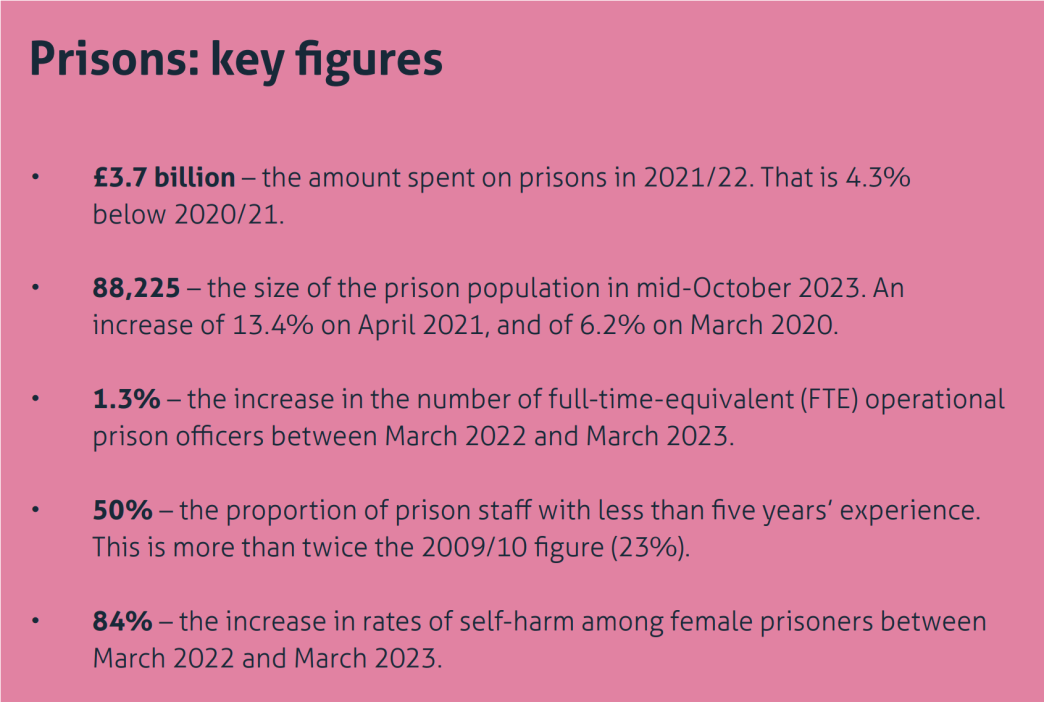

Following deep cuts in the first half of the 2010s, prisons spending increased from 2015/16. The trend continued in the first year of the pandemic, with spending rising by 5.1% in 2020/21, before falling by 4.3% to £3.7bn in 2021/22 as Covid support measures ended. Following the 2022 autumn statement and current inflation forecasts, spending is expected to increase in real terms by 1.6% in 2023/24, leaving spending 1.7% below 2009/10 levels.

In 2021, the government committed to spending £3.75bn to deliver 20,000 new prison places, including 2,000 temporary units, by the mid-2020s. There is also a need to refurbish the existing estate. The backlog of highest priority major capital works was estimated to be £1.4bn in July 2023. 91 Figures provided by the Ministry of Justice. These include projects to address significant health and safety or fire safety risks. The backlog has been increasing (from £900m in 2019/20) by around £225m per year. 92 Figures provided by the Ministry of Justice.

The prison population has grown rapidly in 2023

The prison population fell sharply at the start of 2020, declining by 6% over the year to March 2021. This was the result of pandemic-driven court closures and social distancing, which slowed the number of cases able to progress through the courts, and therefore sentencings, as well as releasing a small number of people early. Between April 2021 and December 2022, the prison population increased at an average rate of 220 people per month. Between December 2022 and mid-October 2023, this increased to 605 per month, helping the total prison population reach 88,225 – the highest level since at least January 2011.

The recent increases are largely due to the progression of court cases previously delayed first by the pandemic and then by barristers’ strike between April and October 2022. 99 Institute for Government interview. Part of this growth is also attributable to the large number of people on remand (people in custody awaiting trial), which has increased by 54.2% between March 2020 and June 2023. 100 Ministry of Justice, Offender Management statistics quarterly: January to March 2023, ‘Prison population: 30 June 2023’ (‘Table 1_1’), www.gov.uk/government/statistics/offender-management-statistics-quarterly- january-to-march-2023 This is again largely due to the backlog in crown courts. 101 House of Commons Justice Committee, The role of adult custodial remand in the criminal justice system: Seventh Report of Session 2022–23 (HC 264), January 2023, p. 6, https://committees.parliament.uk/ publications/33530/documents/182421/default Interviewees also told us that the trend in defendants receiving longer sentences is contributing to the growing size of the prison population, as well as prison recalls.*

* Being returned to prison if the rules of probation are broken.

Prisons are full

In recent months, the capacity crisis has left the prison system at serious risk of collapse. Each prison reports a total operational capacity – the number of prisoners each can hold while accounting for security and the functioning of the prison regime. The closer the prison population is to operational capacity, the harder it is to maintain security and provide appropriate accommodation. Current demand is stretching prisons’ capacity, and makes it necessary to house prisoners in otherwise unsuitable accommodation.

102

Syal R, ‘One in 10 prisons in England and Wales should be shut down, watchdog says’, The Guardian, 25 September 2023, www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/sep/25/one-in-10-prisons-in-england-and-wales-

should-be-shut-down-watchdog-says

In mid-October 2023, the prison population was 1,897 places shy of total operational capacity – the closest recorded level – compared to 3,624 the previous year.* This has happened despite growth in prison places and staff over this period and an even bigger increase in the reported total operational capacity.

Prisons also publish a certified normal accommodation (CNA) level – the prison service’s own measure of how many prisoners can be held in good, decent accommodation. Since 2011, when this data was first published consistently, the prison system as a whole has been operating above its CNA. The increase in the prison population between May 2021 and September 2023 means just 10.6% of prisoners are not being held in accommodation judged ‘decent’ by the prison service itself, compared to 2.0% at the start of this period. 103 Ministry of Justice, Prison population figures, 2011 to 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/prison- population-figures-2022 The Prison Governors Association has previously warned that attempts to increase capacity further within the existing estate (for example, by housing more prisoners in existing cells) would be met with legal action. 104 Albutt A, ‘We’ll sue if you increase prison capacity, governors tell Raab’, Inside Time, 7 March 2023, https://insidetime.org/well-sue-if-you-increase-prison-capacity-governors-tell-raab

While there is considerable uncertainty over the speed at which the crown court backlog will be cleared, the impact of the extra police officers and sentencing policy, the Ministry of Justice’s (MoJ) central projection is that the prison population will grow to 94,400 by March 2025, some 7,800 more than in July 2023.

114

Ministry of Justice, Prison Population Projections: 2022 to 2027, 23 February 2023, www.gov.uk/government/ statistics/prison-population-projections-2022-to-2027

However, the government expects to be able to build only around 2,600 places between July 2023 and June 2025.**,

115

House of Commons, ‘Prison Accommodation’, Question for Ministry of Justice (UIN 194333), tabled on 17

July 2023, answered on 20 July 2023, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/ detail/2023-07-17/194333

Despite pledging to build 20,000 places by the mid-2020s, these places are instead more likely to be delivered by the end of the decade.

116

Syal R, ‘Plan for 20,000 more prison places in England and Wales won’t be complete until 2030’, The Guardian, 29 September 2023, www.theguardian.com/society/2023/sep/29/plan-for-20000-more-prison-places-in- england-and-wales-wont-be-complete-until-2030

That would mean the number of prisoners growing around three times faster than the prison estate’s capacity to accommodate them, leaving the prison population substantially higher than even the maximum theoretical capacity of prisons. This maximum capacity itself comprises a number of Victorian-era prisons, which, according to HM Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP), would ideally be shut down.

117

Syal R, ‘One in 10 prisons in England and Wales should be shut down, watchdog says’, The Guardian,

25 September 2023, www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/sep/25/one-in-10-prisons-in-england-and-wales- should-be-shut-down-watchdog-says

Several attempts have been made to try to control the size of the prison population. Most recently, the government has been forced to announce policy changes to allow for early releases for some lower level offenders, and will legislate to suspend some shorter sentences. 118 Ministry of Justice and The Rt Hon Alex Chalk KC MP, ‘The Government’s approach to criminal justice’, oral statement to parliament, 16 October2023, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-governments-approach- to-criminal-justice Occasioned by the acknowledgement that prisons were dangerously close to full, these measures will likely increase short-term capacity. However, they are only the latest in a string of attempts to stem the population.

Controversially, the government has previously advised judges to consider prison capacity when sentencing.

119

Inside Time, ‘Judges are asked to jail fewer people’, 13 March 2023, https://insidetime.org/judges-told-to-jail-

fewer-people-because-prisons-are-full

Similarly, magistrates’ sentencing powers were halved (having been increased from six to 12 months less than a year prior) due to limited prison space.

120

Ministry of Justice, Letter from Damian Hinds (Minister of State for Justice) to Sir Robert Neil (Chair, Justice

Select Committee), 4 May 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/39864/documents/194271/ default

Non-essential prison maintenance has been postponed so as not to diminish prison capacity in the short term, though this could store up problems for the future. An agreement was also reached with the National Police Chiefs’ Council (‘Operation Safeguard’) to allow the government to temporarily use up to 400 police cells to provide extra short-term capacity.

121

Ministry of Justice, Letter from Damian Hinds (Minister of State for Justice) to Sir Robert Neil (Chair, Justice

Select Committee), 4 May 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/39864/documents/194271/ default

This has been criticised by HMIP for failing to cater for the often complex needs of prisoners.

122

Taylor C, ‘Why the prison population crisis is everyone’s concern’, blog, HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2 August 2023, www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/chief-inspectors-blog/why-the-prison-population-crisis- is-everyones-concern

While the most recent changes may increase capacity, they are not necessarily the long-term fixes that the government will have to find to avoid a cycle of prison population crises.

* Based on monthly data releases.

** One problem the government has faced in delivering on its pledge of 20,000 extra places is gaining planning permission for several new prisons, https://insidetime.org/exclusive-new-prisons-cant-open-before-2027- prison-service-official-admits

The number of prison officers grew in the past year, but retention is still poor

The overall number of operational prison officers increased by 1.3% in 2022/23, though this still leaves total staff levels 10% below 2009/10.* This means the number of prisoners per operational staff member has increased to 3.8 in June 2023, from an estimated 3.5 in June 2010.

The number of joiners increased 12% over the year, to 4,314, while the number of leavers decreased slightly by 1.7%, to 3,331. This is a slight improvement on the number of leavers from last year, but attrition is still high – with 15% of the total band 3–5 operational workforce leaving the prison service in 2022/23.

Indeed, barring a pandemic-induced fall in 2020/21, the leaving rate has increased every year since at least 2009/10, when it was just 3.4%. Resignation is the biggest driver, accounting for two thirds (66.8%) of all leavers in 2022/23. 124 Ministry of Justice, HM Prison and Probation Service workforce quarterly: March 2023 (Tables 11 & 12), 18 May 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hm-prison-and-probation-service-workforce-quarterly- march-2023 Dismissals due to conduct or poor attendance are another big driver. One interviewee told us that the high dismissal rate was due in part to unsuitable candidates passing poor vetting processes. They also blamed insufficient support for inexperienced staff, leaving them ill equipped to manage the ballooning prison population.

The MoJ has argued that, along with leadership and career progression, health and wellbeing is another key driver of staff attrition.

128

Justice Select Committee, The prison operational workforce, Oral evidence (HC 917), 18 April 2023, question 288, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13030/pdf

Furthermore, prisons face competition from services like the Border Force, police and private sector employers, who often offer safer conditions, better financial incentives and more flexible working arrangements.

129

Prison Service Pay Review Body, Twenty First Report on England and Wales 2022, CP 729, The Stationery Office,

p. 27, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/ file/1092253/PSPRB_2022_E_W_report.pdf

* This refers to bands 3–5 operational staff (front-line officers, supervisors and managers).

Many staff are inexperienced and sickness absence remains high

Prison capacity is a function not just of physical space but also of having enough staff with the right experience to make best use of that space. The loss of experienced officers can harm the quality of support and supervision prisoners receive, as newer staff are both less able both to cope with difficult situations and to build long-term relationships with prisoners.

Deep staff cuts from 2010 onwards meant the prison service lost many experienced staff, leaving new officers learning from a much less experienced workforce. 130 Atkins G, Davies N, Wilkinson F, Pope T, Guerin B, Tetlow G, Performance Tracker 2019, Institute for Government, 5 November 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/performance-tracker-2019 Indeed, the workforce has become increasingly inexperienced over the last decade. The proportion of officers with more than 10 years’ experience has nearly halved in recent years, from 61% in 2016/17 to 31% in 2022/23.

There has been an improvement over the past year in the availability of staff, with the number of sick days declining 13% in 2022/23 (driven by a 42% decline in days lost due to epidemic/pandemic over this period). However, the number of days lost to sickness is still 24% higher than in 2019/20.

Staffing problems mean prisons are still unable to safely unlock prisoners

Even though Covid restrictions in prisons were formally lifted in mid-2022, the HMIP found in July 2023 that many prisoners were spending considerably less time out of their cells than had been the case before the pandemic. 138 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales, Annual Report 2022-23 (HC 1451), HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 5 July 2023, pp. 42, 61, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/ uploads/attachment_data/file/1167739/hmip-annual-report-2022-23.pdf

Among prisoners surveyed across 2022/23, some 42% of men spent less than two hours out of their cells during weekdays, rising to 60% during the weekends. For women’s prisons the figures were 36% and 66% respectively. 139 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, Weekends in prison, HM Inspectorate of Prisons, March 2023, www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/04/Weekends-in-prison-web-2023.pdf Inadequate staffing levels may also prevent prisons being able to accommodate new prisoners even when refurbished cells are ready to be used. 140 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, Report on an unannounced inspection of HMP Birmingham, HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 9 February 2023, p. 3, www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/ sites/4/2023/05/Birmingham-web-2023.pdf

Workforce shortages and staff inexperience at a time of over-populated prisons explains much of this.

141

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, Weekends in prison, HM Inspectorate of Prisons, March 2023, www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/04/Weekends-in-prison- web-2023.pdf

,

142

Institute for Government interview.

Many staff have no experience of pre-pandemic regimes and simply do not feel confident allowing prisoners out of their cells to a healthy extent; HMIP has also argued that the rises in prison violence in the last decade (discussed below) also explains this reticence.

143

Taylor C, ‘Why are our prisons still in lockdown?’, The Spectator, 21 January 2023, www.spectator.co.uk/article/

why-are-our-prisons-still-in-lockdown

Many prison officers who saw violence rates plummet during the lockdowns may believe that is the only way to control violence. When prisoners do leave their cells, staff are similarly less able to manage violent behaviour.

144

House of Commons Justice Committee, The Prison Operational Workforce, oral evidence, HC 917, 21 March

2023, question 156, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/12865/pdf

Staffing problems limit access to rehabilitative activities

Keeping prisoners locked up or in overcrowded conditions limits their access to critical services. Dominic Raab, when justice secretary, wrote in February 2023 that “operating close to capacity” will result in “reduced access to rehabilitative programmes”. 156 R v Arie Ali, [2023] EWCA Crim 232, https://caselaw.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ewca/crim/2023/232 Similarly, HMIP has sounded the alarm over the potential for overcrowding to hinder purposeful activities. 157 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales, Annual Report 2022-23 (HC 1451), HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 5 July 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/1167739/hmip-annual-report-2022-23.pdf Ofsted has also argued that limited access to, for example, individual learning plans linked to prisoners’ sentences may result in missed opportunities to reduce reoffending rates and successfully rehabilitate prisoners. 158 House of Commons Education Committee, Not just another brick in the wall: why prisoners need an education to climb the ladder of opportunity: First Report of Session 2022–23 (HC 86 incorporating HC 56), May 2022, p. 19, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/22218/documents/164715/default

Shortages of prison officers have been compounded by difficulties recruiting and retaining prison educators. Comparatively poor pay, unsafe conditions and the lack of career development opportunities inside prisons has contributed to hundreds of vacancies and increased use of agency staff to provide prison education. 159 House of Commons Education Committee, Not just another brick in the wall: why prisoners need an education to climb the ladder of opportunity: First Report of Session 2022–23 (HC 86 incorporating HC 56), May 2022, pp. 27-8, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/22218/documents/164715/default

Over the past year, there has been an increase in the number of starts on accredited programmes – interventions offered to offenders with the aim of reducing reoffending 160 Ministry of Justice, Prison Education Statistics and Accredited Programmes in custody April 2021 to March 2022, Official statistics bulletin, 29 September 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1107740/Prisoner_Education_2021_22.pdf – following the near cessation of these during the first year of the pandemic. However, due to overcrowding and staff shortages, there are still far fewer prisoners undertaking training and education in prisons than before Covid. Indeed, the Justice Committee found that 84% of band 3–5 staff believe staff shortages prevent prisoners engaging in purposeful activities. 161 House of Commons Justice Committee, Prison operational workforce survey (PRI0066), 23 June 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/work/7099/the-prison-operational-workforce/publications Starts of accredited programmes in 2021/22 were 60% below 2019/20 levels, and 88% below 2009/10 levels. Indeed, a recent report on HMP Risley found no accredited programmes were being offered to the 40% of the prison population serving sentences for sexual offences. 162 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, Report on an unannounced inspection of HMP Risley, HM Inspectorate of Prisons, April 2023, www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/07/Risley-web-2023.pdf Similarly, Ofsted has noted the poor overall quality of education provision in men’s prisons, 60% of which are rated as ‘inadequate’. 163 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales, Annual Report 2022-23 (HC 1451), HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 5 July 2023, p. 42, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/1167739/hmip-annual-report-2022-23.pdf

Inexperienced staff provide less effective care to prisoners

Health care in prisons is poor. With prisons struggling to operate more than basic regimes, it is difficult to train staff to adequately cope with prisoners’ health needs (particularly mental health). Indeed, a recent analysis of Independent Monitoring Boards reports have highlighted the impact of the staffing crisis on prisoner health, with increasing reliance on agency staff, shortages in clinicians and chaperones, and inadequate suicide and self-harm training contributing to declines in both mental and physical health support. 164 Coomber A, ‘What do IMBs tell us about prison today?’, blog, Howard League for Penal Reform, July 2023, https://howardleague.org/blog/what-do-imbs-tell-us-about-prison-today/

Interviewees told us that inexperienced staff are less adept at helping prisoners in need of special care. This is concerning given the worse state of health among prisoners than in the general population. The Nuffield Trust has reported that this disparity is particularly acute in those aged over 50 who, for example, suffer higher rates of frailty than in the general population. The over-50 cohort has grown by 6.7% between March 2022 and March 2023, compared to growth of 5.6% in the number aged under 50. 165 Davies M, Hutchings R, Keeble E and Schlepper L, Living (and dying) as an older person in prison, Nuffield Trust, April 2023, www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-04/Nuffield%20Trust%20-%20Older%20 prisoners_WEB.pdf

This loss of experienced staff may also contribute to the number of deaths in prison. One report found that prison staff’s lack of understanding of procedures for monitoring suicide and failures of communication between prison and health staff are common concerns among inquests and coroners’ reports relating to deaths in prisons. 166 Inquest, Deaths in prison: IA national scandal, January 2020, www.inquest.org.uk/Handlers/Download. ashx?IDMF=bb400a0b-3f79-44be-81b2-281def0b924b

Violence decreased dramatically at the start of the pandemic, but has steadily increased since

Incidents of assaults on staff and prisoners grew dramatically – the latter doubling – between 2012/13 and 2017/18, before starting to fall in 2018. This has been attributed to a declining prison population in that period, along with greater investment in staff, and policies like the Challenge, Support and Intervention Plan for managing violent offenders. 171 Institute for Government interview. This initial decline was accelerated during the pandemic, as prisoners were physically unable to spend as much time together during lockdowns. 172 Atkins G, Kavanagh A, Shepheard M, Pope T and Tetlow G, Performance Tracker 2021, Institute for Government, 18 October 2021, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/performance-tracker-2021 However, between Q2 2020 and Q1 2023 the number of prisoner- on-prisoner assaults grew by 56.9%. Overall, there was a 31.5% increase in the total number of assaults per 1,000 prisoners in men’s prisons, and a 81.9% increase in women’s prisons.

Similarly, a decline starting in 2018 of assaults on staff was accelerated by the onset of the pandemic. Since then, assaults on staff have remained broadly flat, but are still higher than at any point before 2015/16 (although the headline figures obscure variations in the performance of individual prisons).

The recent rise in assaults on prisoners has been attributed to the easing of lockdown restrictions in some prisons, and particularly to the frustration among prisoners at being locked up for so long, 173 Independent Monitoring Boards,National Annual Report 2021–22, October 2022, https://cloud-platform-e218f50a4812967ba1215eaecede923f.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/sites/13/2022/11/22-10-04-IMB-National-21-22-Annual-Report-FINAL-ver… compounded by the inexperience of many staff. 174 Independent Monitoring Boards, National Annual Report 2021-22, October 2022, p.11, National Annual Report 2021–22, October 2022, https://cloud-platform-e218f50a4812967ba1215eaecede923f.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/sites/13/2022/11/22-10-04-IMB-National-21-22-Annual-Report-FINAL-ver…

Similar reasons are likely driving incidents of ‘protesting behaviour’, which are categorised as follows:

- Barricades: using barriers to deny access to all or parts of a prison

- Hostage incidents: holding people against their will

- Concerted indiscipline: two or more prisoners not complying with instructions

- Incidents at height: incidents taking place above or below ground level.

Incidents of all four categories increased in 2022/23, following falls in incidents at height and barricade incidents at the onset of the pandemic, and longer term declines in hostage and concerted indiscipline incidents. While hostage taking is still less prevalent than in 2012/13 (the earliest year for which data on all types of protest behaviour is available), the other three are much more common, with nearly twice as much concerted indiscipline, nearly three times as many barricade incidents in 2022/23, and seven times as many incidents at height.

Prisons urgently need to address these trends. However, we have heard that efforts to do so – as well as efforts to design and implement new post-pandemic prison regimes – are being significantly disrupted by the pressures of housing a rapidly expanding population.

Rates of self-harm are at record levels in women’s prisons

Incidents of self-harm are markedly different between men’s and women’s prisons, with rates far higher in the latter. In Q1 2023 alone, there were 1,683 incidents of self- harm per 1,000 female prisoners, equating to 5,469 incidents overall. This compares to 140 incidents of self-harm per 1,000 male prisoners, and 11,074 incidents overall.

Between 2012/13 and 2019/20, rates of self-harm per prisoner grew by 61.0% in women’s prisons and 51.7% in men’s prisons. However, the trends diverged after the onset of the pandemic. In women’s prisons, the rate increased by a further 79% between 2019/20 and 2022/23, and HMIP has warned that prison officers and staff are inadequately trained to care for women with more complex health needs. 176 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales, Annual Report 2022-23 (HC 1451), HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 5 July 2023, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/1167739/hmip-annual-report-2022-23.pdf In contrast, incidents of self-harm per male prisoner fell by 8% over the same period.

- Topic

- Public services

- Department

- Ministry of Justice

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government