How to get to grips with departmental budgets: A practical guide for ministers

What every new secretary of state needs to understand about departmental budgets.

Introduction

When a new government is formed, or a reshuffle occurs, new secretaries of state usually arrive in their departments with plenty of ideas about what they want to do or achieve. But the departments they inherit do not start with a blank slate.

As a new minister, before you can get started on any new plans, you need to understand what the department is already doing, where existing pressures are and the possible impact of any changes of direction. Central to understanding a department is understanding its budget, and you will want to get to grips with it, and how to work with officials to make changes to it, fast.

The department will be working to a multi-year funding allocation decided in the most recent spending review. Government spending is allocated in a budgetary process that can seem baffling to newcomers to government. For instance, the budgets of Whitehall departments can differ greatly – not just in terms of size, but in how they are spent and how quickly changes can be made. Unless a new government introduces an early change to departments’ funding settlements that sees an increase in the budget, doing new things will usually mean doing less of something else.

There are several key issues, covered in this short guide, that every new secretary of state coming into a department needs to understand, and key questions to ask officials.

Key questions

- What is the department spending money on and who is spending it?

- Where are there (unfunded) pressures in the current budget in terms of delivering current policies or services?

- What is the department’s flexibility to change the current budget?

- What are the consequences of any changes, how could these be made, and what are the mechanisms for doing so?

- How can you probe what is happening in the department?

- How will new decisions affect a future spending review?

- Who scrutinises the department’s spending?

Key concepts

- DEL: Departmental Expenditure Limits – the budget available to Whitehall departments to cover the costs of predictable areas of spending (such as delivery of public services, salaries, and maintaining and improving buildings and infrastructure), set at spending reviews with a specific amount available each year and usually divided between capital and resource spending (see below).

- AME: Annually Managed Expenditure – demand-led spending, on things like pensions and benefits, where budgets are not fixed in advance.

- Capital: spending on things that are expected to produce an enduring asset for the public sector – like infrastructure, IT and buildings.

- Resource: day-to-day spending on things like salaries, medicines and other recurring purchases.

- Spending review: a cross-government exercise to plan budgets for future years, managed by the Treasury.

What is the department spending money on and who is spending it?

When first coming into government, new secretaries of state need to understand what their department’s existing budget looks like. Every department will already have a committed budget. By May or June in any financial year each will have got its spending allocation for at least that year and will have allocated that to all the agencies that spend money on its behalf. Departments may also have budgets for the next couple of years – but these will tend to be less committed. Newly created or merged departments will be working out what budgets they have inherited from their predecessor organisations.

You need to know who is spending this pre-existing budget and what on. Civil servants in the department should have prepared this information thoroughly, and be able to give a clear overview of the department’s detailed spending plan and what staff are working on.

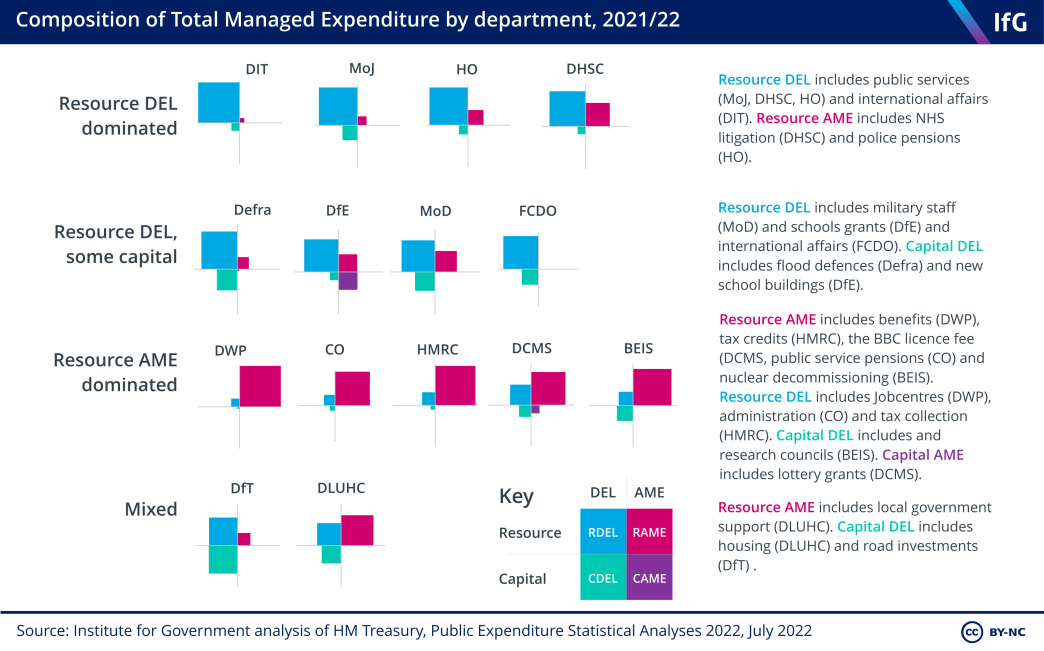

This information will vary greatly from department to department. Some departmental budgets are dominated by cash-limited spending on programmes and grants agreed through spending reviews (departmental expenditure limits, DEL), others by demand-led spending (annually managed expenditure, AME) on things like pensions and welfare.

Being set at the spending review means DEL is a fixed envelope but could be reallocated; AME is determined by demand so is less fixed but as a result does not constitute a pot of money that the department can choose to spend elsewhere.

You also need to understand resource (day-to-day) and capital (investment) spending. Both DEL and AME can come under either category, but since 1998 these have been separated to prevent departments diverting money earmarked for investment into resource spending to manage immediate pressures or reduce borrowing.

Departments also vary in how much direct control they have over their spending. Some have a lot of control over how their resources are deployed (direct management), which includes staff costs as well as spending on goods and back-office services. Others fund public bodies (also known as arm’s length bodies or ALBs, or quangos), which have varying degrees of day-to-day independence from ministers but whose strategic objectives are set either by them or by their departments. Some departments pay organisations that are independent of central government (for example, local government and NGOs) in the form of grants, which gives central government comparably little control over how the money is spent.

Flexibility may also be limited by the extent of existing contractual commitments, legal obligations and some programmes that may seem a low political priority but that are an essential part of a department’s functions. So as well as tallying up the amounts spent on programmes, ministers also need to understand the rationale behind them.

Finally, you will want to understand how different spending streams are supposed to contribute to their department’s outcome delivery plan (ODP). These are supposed to set out departments’ main priority outcomes and the metrics that will be used to judge their performance. Looking at the budget through this lens may help focus attention on areas that are riper for cuts; for example, those that contribute to outcomes that have been downgraded or even abandoned.

Understanding what budget is available, what categories it falls into and how and where it is being spent will enable you to make sure that your departmental budget is being used in the way you want.

Where are there (unfunded) pressures?

Spending reviews settle budgets after lengthy arguments with the Treasury and horse-trading within government. But the reviews are often tight, and departments may not feel their budget is adequate to meet the policy priorities their ministers have already set, or there may be additional pressures – for example, from unexpectedly high inflation, wage pressures or other crises – that have strained their finances since. And there can be other planned changes that might have knock-on effects for some departments: if there are minimum wage increases or tax changes planned, for example.

This means you cannot take for granted that your department’s budget will allow you to deliver the policies and services to which it is already committed, let alone launch any new initiatives, so you need to thoroughly understand these existing pressures soon after taking office.

Probing officials on where potential budget pressures might arise will help you prepare for and react to unexpected events.

What is the department’s flexibility?

While the overall size of the budget is committed, there may be more flexibility on where the money goes. However, the timing of any changes will be key and there will typically be more flexibility to make changes to the budget for the following year than to make in-year changes. Civil servants may (strongly) play down the flexibility available to ministers, but there are a few questions new ministers can ask to help establish how much scope they have to make changes:

- How is the money committed? Whether the money is committed through contracts, staffing or other firm plans can affect how easy it is to make changes.

- How much of the money does the department manage directly? Whether the money sits with the core department or is out in ALBs or grants also has an impact on ministers’ ability to influence spending.

- Where are there existing legal, contractual or political commitments? Things like the legislative target to spend 0.7% of GDP on aid or the triple lock on pensions may require legislation to amend.

You will also need to think through what flexibility they have in your or your party’s own plans and what that would mean for the budget:

Has your party already committed to additional spending in its manifesto? One of the key lessons for government is that making detailed expensive commitments in manifestos might help win elections but can seriously reduce ministers’ discretion once in office, particularly if the public spending envelope is tight.

Are any ‘machinery of government’ changes planned? Moving areas of policy from one department to another or merging departments means changes in budgets. Typically, new departments that depend on transfers from existing ones will find themselves underfunded on core administrative costs. While the Treasury often argues that the cost of any departmental restructure should be absorbed within existing budgets, previous Institute for Government research has shown that the costs of a departmental merger can be around £15 million, on setting up new IT systems, buildings and so on. However, this is often much less than the hit to productivity, and in some cases staff morale.

How does the government’s overall plan for public spending affect the scope for change in future departmental budgets? Future scope for change can have an impact beyond what a minister might do in the current spending review timeframe and affect how they can plan future spend. A new spending review may seem like an opportunity to get more money or a better time to make changes. However, departments could find that the new government is planning on restricting budgets further. In 1997, Gordon Brown as chancellor chose to maintain the Conservatives’ previous overall public spending envelope for three years so departments were restricted in what could change.

Asking questions about what flexibility is available in the budget, and thinking through external pressures, will mean you can adapt your department’s budget in the most sensible way.

What are the consequences of any changes?

New ministers also need to understand the consequences of making changes – in terms of money, policies and how these affect the public, and politically. Most importantly, you should demand evidence on the likely policy effects of changing, cutting or introducing a programme. If evaluations show convincingly that a programme has contributed towards a key government objective that remains high priority, shifting away from that approach will be riskier, while increasing its budget may seem like a sure bet. If the opposite is true, it follows that this could provide a good opportunity to spend the money elsewhere.

If you are sure that spending on a programme does need to be reduced, you should still consider the upfront costs of changing policy too quickly. When the government cut foreign aid from 0.7% GDP to 0.5% this amounted to a cut of around £4–5 billion. But, in the short term, that also meant ending many programmes where funds were already committed and the government had to buy them out. Similarly, any changes to funds already allocated on staffing may mean redundancy payouts.

When looking to spend more on day-to-day programmes in the short term, one temptation is to reallocate money that has been allocated to capital projects. This has been a common approach in recent years, despite tighter Treasury rules since 1998. But this undermines investment and can have a wider impact on planning for the public sector where it is dependent on capital investment.

Topping up or cutting budgets outside of spending reviews creates uncertainty that makes it harder for public service leaders – including council and hospital chief executives – to plan and invest well. In response to radical changes made by Theresa May’s government to spending plans originally set out in the 2015 spending review, NHS finance directors cut back on planned capital projects and prioritised urgent short-term schemes instead.

Late changes to capital spending plans can also create problems for private sector firms; for example, by making it difficult for contracted companies to hire staff or invest in necessary equipment.

If you are satisfied that a change could be made in the short term without major disruption, you will also want to consider how – and by whom – any change will be implemented. In particular, if money is distributed by an ALB or through grants, the level of control the department will have over the ultimate consequence of any cuts may be limited.

A change to the budgets to an ALB or local government might, for example, eventually lead to the cutting of grants to particular community groups or businesses who are very vocal about it, or perhaps a low-profile but locally important piece of infrastructure might be cancelled or delayed. You will need to be prepared for the unintended consequences of any cuts or changes.

Changing spending priorities will inevitably have an impact on your department’s policies and programmes – make sure you’ve interrogated those impacts before you make any decisions on moving budgets around.

How could changes be made?

Thinking through the budget and the impact of any changes or new policy should be an early preoccupation for both the ministerial and senior official teams. These conversations need to focus on two things: how much money will the department need to spend on any new commitments, and when does it need to start spending?

The answers to these will make clear what headroom is needed to create or change spending priorities (assuming that the overall envelope will be unchanged in the first year at least). New ministers should task the permanent secretary and most senior finance official to come back within a short space of time with costed options for change – making clear from the start any areas they assume ministers would regard as ‘untouchable’ and why.

You will also need officials to alert them to potential risks attached to the options, including the likely reaction of those with whom the department deals. That means engaging the chairs and chief executives of the department’s delivery bodies, who may spend much of the departmental budget and will need to implement any changes.

All ministers also need to work with the Treasury. This is particularly important if asking for more resources – the Treasury will need to be convinced that the department has reviewed its existing spend exhaustively. There is no one way to go about this. But you will need to make clear to officials that reordering the budget to meet the new priorities is a critical task and that they expect them to come up with realistic and deliverable options.

In some areas ‘zero-based’ reviews – looking at the entire budget – may be of use. In others the focus will be on the scope for marginal changes. Or asking teams to explain how they would achieve percentage cuts as a starting point – a Treasury favourite – may be a good way to interrogate budgets.

Making high-level budget decisions is only one part of the role of a minister – thinking through how to make those changes is also essential.

How can new ministers probe their departmental budget?

For those moving into government from opposition, there is a limit to how much of a department’s spending will be accessible from the outside. In advance of taking office, published accounts and other sources such as National Audit Office reports on each department provide some insight into the existing budgets. But the line-by-line detail of how the department’s budget is allocated is not available publicly so there is a limit to how much understanding potential ministers can amass before taking office.

For oppositions, ‘access talks’ should allow shadows to discuss current commitments, some of the risks facing the department and general points about the budget, particularly where it covers matters already in the public domain. But permanent secretaries are not able to reveal sensitive details about current government policy.

Ministers joining after a reshuffle, or as part of a new government following a change of prime minister, may well have had no warning of which department they will end up in, so will be starting fresh. But for all new ministers, the day one briefing pack prepared by the department and initial meetings with the permanent secretary and senior officials should cover what is going on in the department and where money is allocated. Departments that get this wrong, get their numbers wrong or can’t answer questions about who is doing what in the department and what it is costing will understandably quickly lose confidence of new ministers.

Depending on your prior relationship with the department, you may have a good sense of its budget already or none at all. Make sure that officials provide you with a thorough overview and that you can build your knowledge quickly.

How will new decisions affect a future spending review?

One of the questions that will flow from these early decisions about the department’s budget is what they will mean for any future spending reviews. This will depend on when, within a spending review cycle, a new government takes office.

As noted, it is easier to make changes to future financial years than to the existing one – but beyond that, the changes to the budget and discussions about future spending will start to shape the department’s response to a future spending review round. It will particularly affect the central question of whether the department can live within the spending envelope it has been set and how decisions about a forthcoming spending review might affect the timeframe over which changes are planned.

The exact process for any spending review is at the discretion of the chancellor and the chief secretary to the Treasury (who has responsibility for overseeing the process and subsequent department spending decisions).

A new administration – whether taking office after an election, or after a change of prime minister – may choose to hold an ‘emergency’ budget and/or spending review to set out their priorities and respond to any crises or key issues that arose during the end of the previous administration.

Budgets and other fiscal events set the overall amount of money the government is spending, and sometimes include specific funded increases for departments. But it is only during the spending review process that the full negotiation over the future budgets of departments takes place, usually over a period of months and requiring a considerable amount of work by the department to prepare bids and go through negotiations. Because government spending funnels out into various other parts of the public sector and other bodies many different perspectives and inputs need to be taken into account.

Spending reviews are, necessarily, a political process. They often require tough choices between priorities, particularly when national finances are tight. For departments, that means being clear about their own agenda and priorities, as well as the assumptions on which their bids are based.

Many of the discussions described above on making changes to a department’s budget can therefore be vital to participating in a successful spending review in future years. For ministers, it means understanding the department’s position and the detail of its budget pitch.

Understanding the department’s position and the detail of its budget pitch is crucial ahead of a spending review, so you can best negotiate with the chancellor, chief secretary and wider Treasury.

How will you be scrutinised on departmental budgets?

All of the decisions being made about the department’s budget will end up being scrutinised in some fashion. A key role for parliament is to authorise government expenditure. It also has several mechanisms to scrutinise government spend, both before it is made and in retrospect.

While financial bills and other proposals that bring costs attached are all subject to varying degrees of scrutiny by parliament, it is through departmental select committees and the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) that the House of Commons does most of its scrutiny of government spend. The PAC looks not only at the budget itself, but also the various decisions on policy aims, delivery and implementation that have an effect on how well money was spent.

Select committees, and in particular the PAC and the Treasury Committee, also look at the competency of financial management specifically. The Scrutiny Unit is a specific resource set up to support select committees in examining supply estimates, department budgets and annual reports. The PAC receives reports from the Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG, who heads the National Audit Office) in examining value for money, efficiency and effectiveness of government departments and their affiliated bodies.

Ministers are accountable to parliament for all aspects of their department’s performance. But on financial matters, permanent secretaries are directly accountable to parliament in their role as accounting officers. This means that they need to justify decisions made by the department, and it is through this role that permanent secretaries might ask for a written direction from a minister if they feel that a spending decision does not meet the standards set for accounting officers on regularity, propriety, value for money or feasibility.

Taking seriously the discussions you have with parliament about your department’s budget, and working closely with your permanent secretary, will help ensure you continue to have the ‘licence to operate’ that parliamentary scrutiny provides.

Conclusion

After any change of prime minister or general election, a new administration is likely to bring both new policy priorities and new ministers. But making change in policy is not only about policy design and delivery, it is also about paying for those changes and using the resources of the department well. And new ministers, particularly if they are inexperienced in government, will need to learn quickly how best to use their position to drive that change.

So as a new minister, particularly a new secretary of state, getting to grips with your department’s budget is crucial – and yet it can be one of the most complex to learn. It can also be one of the most difficult to prepare for, both because the detail of any departmental budget is usually only known to those working inside government, and because the complexities of how public spending operates is often something that many MPs only start to understand in detail with when they become a minister, or serve on one of the public spending-focused select committees.

You will need to rely on civil servants for financial detail, but you should also feel confident to challenge and ask probing questions, and, if you are setting new priorities that require a reordering of their department’s budget, you should make clear to the permanent secretary that you expect them to come up with realistic and deliverable options.

Above all, however, new ministers also need to understand the consequences of making changes – in terms of how money is spent it, who spends it, and how this will affect the public. Spending public money is at the heart of everything ministers do, understanding how to spend it as efficiently as possible should be a high priority for any new or aspiring minister.

- Topic

- Ministers Public finances

- Keywords

- Budget Public spending Spending review Economy Public sector Cabinet Austerity Government reshuffle General election

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Series

- IfG Academy

- Publisher

- Institute for Government