The end of Boris Johnson’s premiership

To mark the end of Johnson’s premiership we have brought together analysis from across the IfG which tells the story of the key moments of his tenure.

On Monday 5 September, Boris Johnson’s successor as prime minister will be announced. The following day Johnson’s time in office will come to an end. Those three years, one month and 14 days have been as controversial as they have been dramatic, careering from the highs of a huge general election victory to a series of embarrassing by-election defeats, from marriage and the birth of two children to three nights in an intensive care unit in hospital.

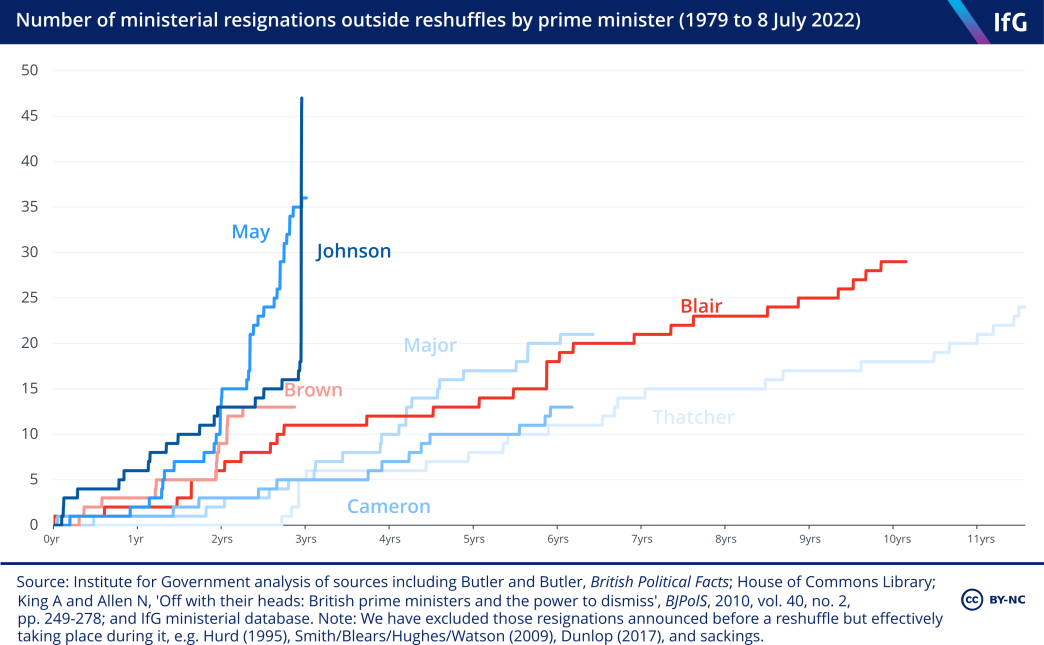

As prime minister Johnson, unlawfully prorogued parliament, won an 80+ seat majority, took the UK out of the EU, locked down the whole country three times, caught Covid himself, saw two advisers on ministerial standards resign and lost four by-elections. More ministers resigned from his government than any other in British history, with that record-breaking tally eventually bringing his time in No.10 to an end.

His premiership will be remembered for many things: his success in ‘getting Brexit done’, and the unfinished business resulting from the UK’s departure from the EU; the government’s response to Covid; the impact of the pandemic on the economy; the frequent reorganisations of how the centre of government works; and latterly the UK’s support for Ukraine in the face of the Russian invasion.

To mark the end of Johnson’s premiership we have brought together analysis from across the IfG which tells the story of the key moments and decisions of his tenure, and looks at some of the biggest issues in his successor’s in-tray.

Covid

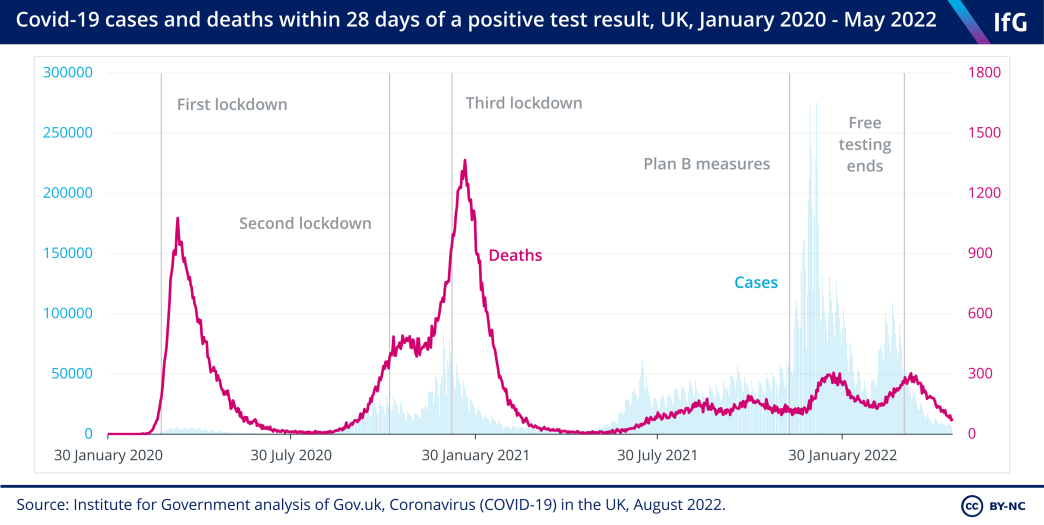

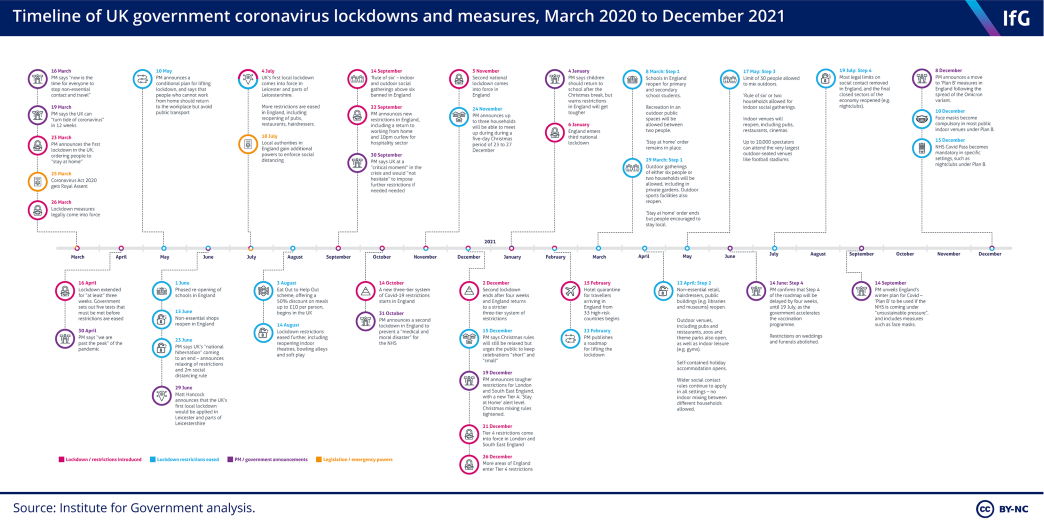

Only a few weeks after Boris Johnson led the Conservative Party to its largest general election victory since 1987, China reported a cluster of cases of pneumonia in Wuhan to the World Health Organization, which were later identified as the novel coronavirus Covid-19. By 16 March cases had spread around the world and Johnson was telling people to stop ‘non-essential contact and travel’. On 23 March, he announced the UK’s first national lockdown.

What followed were three national lockdowns, school closures, unprecedented economic support schemes, roadmaps in which particular restrictions were progressively unlocked, the rule of six, a variety of local restrictions in different areas over different periods, border restrictions, the building and then eventual dismantling of a national testing regime, and a highly successful vaccination programme. Over 200,000 deaths with Covid mentioned on the death certificate have been recorded.[1]

Although the vaccination programme was widely praised, there was criticism of government decision making, communication and delivery. Experts argued that delays to both the first and second national lockdowns potentially led to a large number of avoidable deaths. Confusing and frequently updated lockdown rules failed to drive home key messages, such as the risk of gathering indoors. And the government struggled to establish an effective regime for contact tracing and isolation. As Johnson’s premiership ends the Covid inquiry is just beginning to look into these questions.

Going into this autumn and winter, Johnson’s successor will need to decide the proportion of the population who should receive boosters, what the impact the end of free testing has been and whether the NHS can withstand the pressure if there is another major wave or a new variant emerges.

Vaccines allowed the government to avoid another lockdown when the Omicron variant emerged last winter although Plan B restrictions were put in place. With hospitals already under significant strain, and most people currently much further from their last vaccination, this winter could still pose a major challenge.

Economy

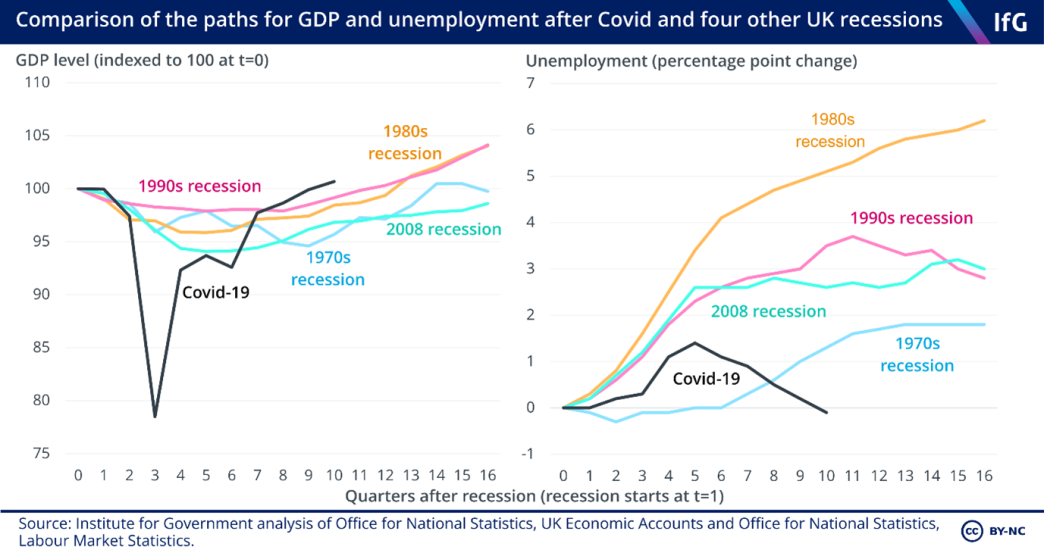

The Covid crisis was one of the most extraordinary economic shocks the UK has experienced. In the height of the first lockdown, GDP fell by more than 20%, and in 2020 as a whole it was 11% lower than the previous year. This was much deeper than any recession since the 1920s. Yet this was also a different type of economic shock – temporary closures enforced by public health – and the Johnson government met that with an extraordinary policy response.

Across 2020/21 and 2021/22, the government spent over £300 billion supporting households, businesses and public services. The support for households was starkest – the furlough scheme meant the government effectively paid the wages of 11 million workers for at least some of the period from March 2020 to September 2021. Alongside support for the self-employed, a boost in Universal Credit and loans and grants to businesses, it meant that the government effectively protected households from the economic turmoil. Despite a much deeper recession than any other in the last 50 years, unemployment barely increased due to this support.

This was an undoubted success for the government, but its handling of the pandemic from an economic standpoint is not immune from criticism. It failed to adapt and improve support schemes such as furlough, and its business loan scheme in particular turned out to be much more expensive than originally planned. Economic policy also sometimes conflicted with broader pandemic control measures, most notably with Eat Out to Help Out and the failure to improve statutory sick pay.

As the country moved out of the pandemic, then-chancellor Rishi Sunak announced higher taxes – the health and social care levy and an increase in the corporation tax rate. While he argued that these were necessary to pay for Covid, in practice the bigger driver was demands on public services such as the NHS, which necessitated a more generous spending review which was delivered in October 2021.

The final months of the Johnson premiership have been consumed by another economic crisis, but the energy bills crisis is very different from coronavirus. Higher inflation means that the Bank of England is now increasing interest rates, which means that fiscal policy should mostly focus on redistributing the pain of the coming crisis rather than trying to boost demand. The government has stepped in to provide some additional support, but more will be needed when the new prime minister is in post. Given how successfully the government protected households from the Covid shock, the public are likely to have even higher expectations of what the government can do to protect them now.

Brexit

Boris Johnson’s government was elected on a pledge to “Get Brexit Done”, and following the 2019 general election the UK did leave the EU on 31 January 2020 with a withdrawal agreement in place. During 2020, the UK remained within the EU’s customs union and single market which meant that very little changed on the ground. But the government’s decision not to extend the transition period meant the civil service had to prepare for a markedly different trading relationship with the EU alongside responding to the coronavirus pandemic and when businesses were already struggling.

A Christmas Eve deal – the UK–EU Trade and Co-operation Agreement – left businesses only six days to digest what the new relationship meant for their trade, and prioritised ‘taking back control’ over retaining access to the EU market. Despite the short timeframe, the disruption to trading arrangements due to the pandemic did initially disguise some of the economic impact of leaving the EU. For example, closed borders limited business travel and delayed the impact of the end of free movement.

It is still too early to assess the impact of the Brexit deal on the economy, but the Office for Budget Responsibility has so far seen no reason to change its assessment that the UK economy will be 4% smaller in the long run than if it had remained in the EU, which is in line with other external estimates before the UK left. The main reason economists expect Brexit to make the UK poorer is the impact on trade: less open economies tend to grow less. And since voting to leave the EU, the UK has traded less overall even as other European economies have increased their trade. However, UK trade performance is more in line with Asia-Pacific countries.

Although Boris Johnson promised an “oven-ready deal” during his election campaign, the Northern Ireland protocol remains a key sticking point. To avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland, the protocol requires Northern Ireland to align with EU law in some areas (maintaining frictionless trade with the EU) which has meant new checks and controls are required on goods in the Irish Sea. A series of grace periods have delayed the full application of the protocol, but there is evidence that the arrangements have caused some disruption to trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland which the UK government and Northern Ireland’s unionist political parties have argued is unacceptable.

The UK and the EU have been in negotiations about changes to the Northern Ireland protocol since 2020, but, in June, Liz Truss, as foreign secretary, introduced legislation which would disapply large parts of the protocol – breaching the treaty signed in January 2020. Both Truss and Rishi Sunak have said that they will continue down this path – which risks longer-term damage to UK–EU relations and continued economic and political instability to Northern Ireland.

The union

As prime minister, Boris Johnson shifted the UK government’s approach to management of the union. ‘No more devolve and forget’ has been the watchword, with the government concluding that Westminster’s hands-off approach since 1999 had created space for nationalism to flourish. This has been accompanied by a steadfast refusal to engage with demands from the Scottish Nationalist Party to hold a second independence referendum.

Under Johnson, the UK government’s union strategy has involved greater willingness to intervene in devolved issues. For instance, contentious bills such as the UK Internal Market Act and Subsidy Control Act have been passed without consent from Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast, as required under the Sewel Convention.

UK ministers have used the new financial powers provided by the UK Internal Market Act to spend money directly in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland through initiatives such as the Levelling Up Fund and the UK Shared Prosperity Fund, the replacement to EU structural funds). Through these funds the UK government has spent money on devolved functions such as local economic development and adult skills. The long-term bet is that raising the profile of UK government activity and programmes will shore up support for the union.

Following the coronavirus pandemic, the Scottish National Party has renewed its calls for a second independence referendum. The SNP has argued that the result of the 2019 general election (in which it won 48 of 59 seats in Scotland) and its victory in the Scottish parliament election in 2021 have provided a mandate for a second independence referendum. The UK government’s approach under Johnson has been to consistently reject calls for a second referendum on the basis that the 2014 independence referendum was a “once in a generation vote”.[1]

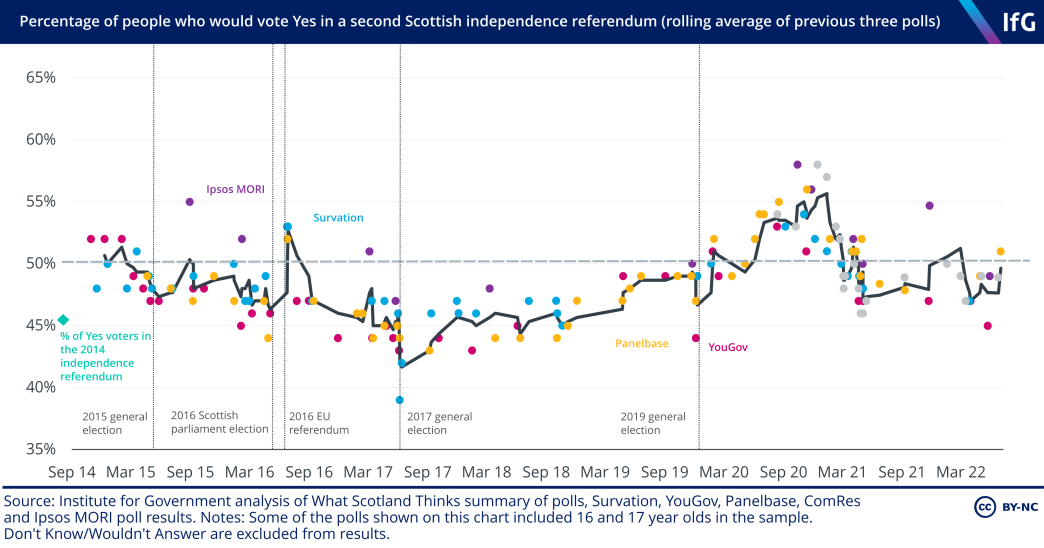

The SNP’s response has been to put forward a bill setting a date of 19 October 2023 for a second independence referendum. The bill has been referred to the Supreme Court, which will rule in October as to whether the referendum can be held without Westminster’s backing. If the decision goes the SNP’s way then saving the union will become the top priority for Johnson’s successor. Even if it does not, then the issue is unlikely to fade away. The opinion polls suggest that Scotland remains evenly divided, as it has been for much of Johnson’s tenure.

In Wales, the pressure on the union may feel less urgent, but discontent at Westminster’s treatment of devolution is just as real. The Welsh government has recently established a new cross-party commission on Wales’s constitutional future, which is exploring options for further devolution and constitutional protections for Welsh devolution. The new PM must decide whether they have anything to offer Wales beyond ‘no more powers’, the pledge that Welsh Conservatives put to the voters – with limited success – at the most recent Senedd election.

Northern Ireland presents a more pressing challenge. The DUP has refused to re-enter government in Belfast until the UK government reforms Boris Johnson’s Northern Ireland protocol, which requires product checks on many goods crossing the Irish Sea. The new PM will have to resolve this issue quickly to avoid another election in Northern Ireland, at which Sinn Féin would be well-placed to extend its lead as the largest party at Stormont.

Under Johnson, the strategy of ‘muscular unionism’ has seen a general deterioration in relations between the UK and devolved governments. The Scottish and Welsh governments have accused UK ministers of disregarding the devolution settlement by adopting major legislation without their consent, and of undermining democratic accountability by spending directly on devolved policy areas.[2]

The coronavirus pandemic, which dominated Johnson’s time in office, has also made voters more aware of the political and constitutional implications of devolution. Health is fully devolved and the ‘lockdown’ legislation to enforce social distancing was implemented on a devolved basis. The result was that at several points during the pandemic there was notable divergence in approach between the four nations of the UK in terms of lockdown regulations.

But despite these tensions, Johnson’s premiership also saw the completion in early 2022 of the review of intergovernmental relations (IGR) and the establishment of a new machinery to facilitate cooperation and joint working between the four administrations.[3] Should Johnson’s successor decide to take a more conciliatory approach to relations with the devolved administrations, these new structures could provide a framework through which to do so.

- www.gov.uk/government/publications/letter-from-pm-boris-johnson-to-scottish-first-minister-nicola-sturgeon-14-january-2020

- See for example: https://gov.wales/written-statement-levelling-fun

- www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-review-of-intergovernmental-relations/review-of-intergovernmental-relations-html

The functioning of government

Johnson’s premiership began with Dominic Cummings, Vote Leave’s campaign director, embedded as his most senior aide and with a mission to reform government. Immediately after the 2019 election Cummings turned to what he said would be ambitious reform of the civil service. But it was clear from the start that any reform programme was dependent on the attention of Johnson as well as Cummings – and that, as the Institute’s Cath Haddon warned at the time, “fire-fighting a political crisis at home or being drawn into major world events will inevitably bump civil service reform out of the grid". Clipping the wings of the Treasury was another ambition that was always going to be hard to achieve.

When Covid emerged longer-term civil service reform took a back seat to combating the immediate crisis. Embers of ambition remained, with a Michael Gove June 2020 lecture making the case for change in Whitehall. But in practice actual changes were piecemeal and it was high profile sackings, rather than deeper reforms, that were the dominant theme of the period. Permanent secretaries were fired and mostly replaced by other Whitehall lifers. Simon Case arrived as permanent secretary in No.10, before taking on the role of cabinet secretary when Mark (now Lord) Sedwill was forced out – provoking questions about civil service impartiality. And the government proposing a breach of international law led to the resignation of the top civil service lawyer and a debate about whether the government was crossing ethical lines.

‘Tsars’ with private sector experience were appointed to help with the coronavirus response, but before 2020 was out so were Cummings and many other former Vote Leavers – his antagonistic style losing him support within government. Lord Udny-Lister was appointed Downing Street hief of Staff, soon replaced by Dan Rosenfield. With Cummings’ departure not enough to reset Johnson’s premiership,resolving the chaos in the centre of government was ultimately down to the prime minister. The new prime minister should prioritise maintaining a more stable immediate team, creating a structure with clear lines of responsibility from the top civil servant and most senior special adviser in No.10, and ensuring everyone in the building speaks for the PM, not their own policy agenda.

In July 2021 a reform plan, the Declaration on Government Reform, was finally launched. It was a welcome statement, but progress on its 30 actions was nonetheless slow. And by the end of Johnson’s tenure reform had become more about preventing civil servants from working from home and reducing civil service headcount to its pre-Brexit number – an arbitrary target that would end up being less effective than a proper evaluation of what the government wanted to do and how many civil servants were needed to do it. Reviving a serious programme of reform, with a workforce plan matching ministerial priorities, rather than the other way around, should be a priority for the new administration.

In the wake of ‘partygate’ there were more changes to No.10 personnel and a new Prime Minister’s Office was announced – but a superficial reorganisation of No.10 was never going to solve the government’s problems. In particular, the question of ethical standards, and how they were upheld, dogged Johnson’s premiership and stemmed from the prime minister himself. From David Cameron’s post-office lobbying to the partygate scandal, there were frequent accusations that Johnson’s government fell short. One key question for his successor is whether they will clean up the reputation of government. The role of independent adviser on ministerial interests has been vacant since Lord Geidt resigned in June – and Liz Truss has suggested that no successor needs to be appointed. These questions, as well as priorities for government reform, should be high up the to-do list of the incoming prime minister.

Supporting Ukraine

Since Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Boris Johnson’s government has been one of the most vocal and active supporters of Ukraine. In the final months of his administration, Johnson’s allies regularly cited the UK’s approach to the Ukraine as one of the biggest achievements of his time in office. Johnson visited Kyiv three times following the start of the war, with his final trip taking place just days before the end of his premiership.

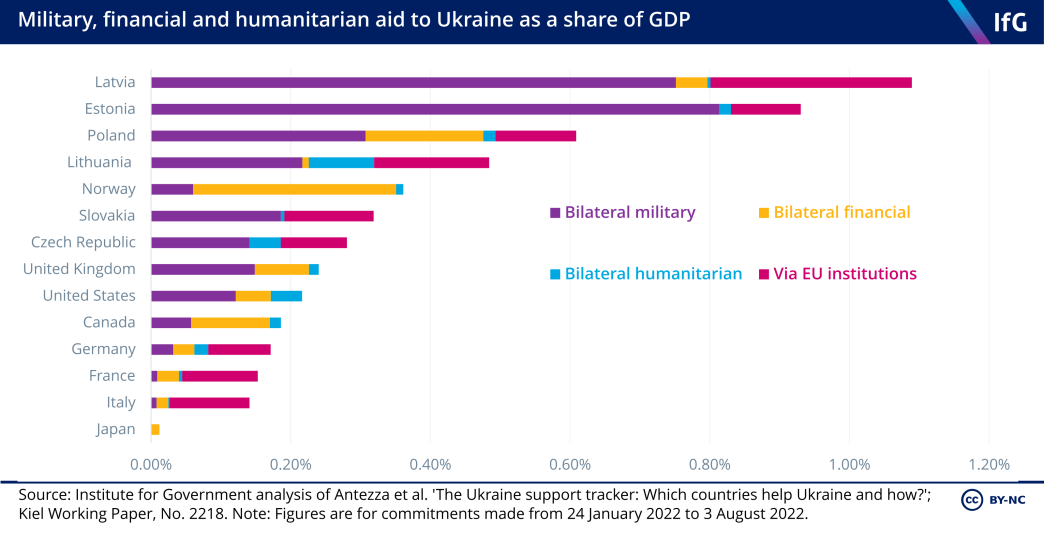

Since the start of the war, the UK has committed £2.3bn in military and financial aid. Estimates compiled by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy show that UK has been one of the largest suppliers of aid to Ukraine among the G7 on a per capita basis.[1] The UK has also played a key role in providing specialist military training to Ukraine’s forces as the war has continued. This built on several years of close bilateral diplomatic and security cooperation between the two countries, which predates the Johnson administration. The UK has provided training to Ukrainian forces as part of Operation Orbital since 2015; in 2016, the UK and Ukraine signed a 15-year agreement on defence cooperation.

Early on in the conflict, the UK also worked in close coordination with the EU and other G7 countries to impose unprecedented and far-reaching financial and trade sanctions on Russia. The UK government froze the assets of leading Russian officials and businessmen and major Russian financial institutions, including the Russian Central Bank. The conflict also prompted the government to rapidly push through the Economic Crime Act through parliament. This gave the government new powers to impose sanctions, and is intended to increase the transparency of property ownership and make it easier to confiscate unlawfully obtained wealth.

While the UK has provided substantial military and financial aid to Ukraine, it has made a much smaller contribution than other European countries to supporting refugees from Ukraine. The UN estimates that in late August there were over 3,840,000 refugees from Ukraine registered for temporary protection in Europe. The UK is the only country in Europe that has maintained visa requirements for Ukrainian citizens. In mid-March, the UK launched the Homes for Ukraine scheme, which provides free visas to any Ukrainian citizen who wishes to come to the UK. However, applicants must have named sponsors who agree to provide accommodation for at least six months. The government has made significant progress in reducing the delays and administrative hurdles which made it difficult for refugees to access the scheme in the early months of the war. Nevertheless, the design of the visa scheme appears may have constrained the numbers of refugees willing or able to come to the UK. In per capita terms, the number of refugees from Ukraine that have come to the UK is among the lowest in Europe.

Both candidates to replace Johnson have made clear they will maintain the UK’s strong diplomatic and military support for Ukraine, although supply constraints may limit the additional military aid that the UK is able to provide in the near term. In the coming months the biggest policy dilemmas of the Ukraine conflict are likely to be domestic, as Johnson’s successor must grapple with the impact of the sharp rise in energy prices caused by the reduction in Russian gas supplies to Europe.

- Antezza A, et al.; “The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which countries help Ukraine and how?” Kiel Working Paper, No. 2218.

- Topic

- Ministers Coronavirus Brexit

- Keywords

- Cabinet Government reshuffle Ethical standards Leadership election Majority government The union Economy Cost of living Ukraine crisis

- Position

- Prime minister

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- Number 10

- Public figures

- Boris Johnson

- Publisher

- Institute for Government