Magical thinking about government needs a dose of reality

UK government needs to reform itself, and we cannot wait until 2025 to begin.

The UK’s political parties are not being honest with the public about the situation in which the country finds itself – the implications of persistent low growth, long-term underinvestment in public services and significant public debt ballooned by the pandemic. Worse, it seems our politicians are not being honest with themselves about the changes needed for the UK government to be capable of dealing with these challenges. Brexit ‘cake-ism’ has evolved into a persistent strain of ‘magical thinking’ among our political classes about the state of the state, and the sufficiency of the strategies they propose to fix it. But reality cannot be denied indefinitely.

The evidence of systemic government failure is staring us in the face: from the Horizon Post Office scandal, which implicates officials and politicians of all parties over the last two decades; to the Covid inquiry, which is systematically exposing the shortcomings in the state; and the seemingly endless examples of unethical behaviour by individual politicians, which repeatedly undermine public confidence in our democratic system. At the same time, ministers have grown used to short-circuiting parliamentary scrutiny while MPs have all but abandoned their responsibilities as legislators.

We can expect to see more magical thinking in the months ahead – with everything that happens in Westminster during 2024 distorted through the lens of the looming general election. Political strategies and decisions will be shaped by the impending poll, and the inevitable temptation will be to over-promise while at the same time reaching for dangerously divisive wedge issues. But short termism, scorched-earth tactics and trap-setting commitments risk undermining the long-term prospects of the country. An outgoing government should take no pride in trying to make the task of its successor even more difficult.

On the contrary, parties seeking the privilege of governing the country after the election don’t just need to convince voters that they have ideas for things they would like to achieve in government. They also need to have serious proposals to change the way in which they will do government. A failure to fix the way we run government will mean many manifesto pledges and campaign promises remain just that – commitments that don’t bridge the gap to reality.

The Horizon Post Office scandal, which implicates officials and politicians of all parties over the last two decades, is an example of systemic government failure.

2023 was a year of limited progress

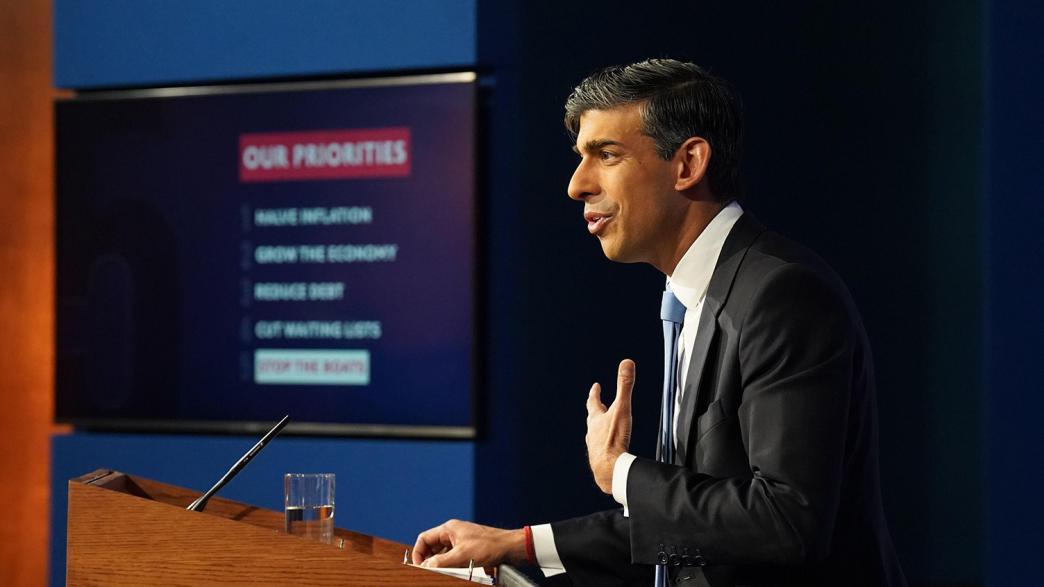

A year ago I warned that 2023 risked being a wasted year. In many ways, so it has proven. Judged against the scorecard Rishi Sunak set for himself – one I argued at the time showed limited ambition – the prime minister has been keen to take credit for inflation washing out of the economy and to point to progress on cutting the number of small boats crossing the channel (though falling well short of ‘stopping the boats’). But growth remains anaemic, drops in hospital waiting lists have proven elusive in an NHS beset by continuing strikes and the forecast that debt will finally begin to fall in 2028/29 relies on implausibly tight, unspecified spending plans.

The government has announced long-term policy objectives in some areas – including reform of A-levels, the first NHS workforce plan for decades, thinking on international development and plans for investment in nuclear power. But little groundwork has been laid to meet these objectives. Some limited progress has been made on government reform – in areas like moving the civil service out of London and improving learning and development. But little has been done to tackle other systemic problems, including underinvestment in public services and infrastructure or the UK’s persistent house-building shortfall. Meanwhile, the government seems to be trying to undermine the UK’s consensus on net zero, even while undertaking what are individually quite sensible measures to make progress. Sunak’s most substantive achievement – resetting relations with the EU after agreeing the Windsor Framework in February 2023 – has still not succeeded in its second aim of restoring devolved government in Northern Ireland, which is suffering even more than the rest of the UK from failing public services.

As we enter 2024, government ministers – and anyone who wishes to become one – need to temper their magical thinking about government with a dose of hard reality. That means being honest with voters about the difficult decisions inherent in running a country, taking those decisions based on evidence, and strengthening the civil service to deliver the policies that result.

Be honest with voters about trade-offs

Both Labour and the Conservatives are likely to campaign on promises to improve growth, reduce the tax burden and improve public services. But growth forecasts are bleak. The so-called headroom the government has used to reduce some of the tax increases it has previously imposed is based on implausibly tight spending plans for public services.

Whoever wins the election will face extremely difficult decisions. Current spending plans are a fantasy that would deal a body blow to already fragile public services. Both parties claim that service reform will deliver better performance. But while there is much room for improvement in services, almost all reform will require upfront investment. The next government will therefore need to cut services or raise more revenue to fund improvements, or a combination of both.

It might not be electorally advantageous to commit to either of those now. But elections are about getting a mandate for difficult decisions. In 2010, the Conservatives used their campaign to secure a mandate for major cuts to public spending. The cuts implied by current plans are not as big as in 2010, but if carried out would see unprotected services (prisons, schools, local government) suffer the biggest cuts since austerity began. Those cuts would fall on services that have faced more than a decade of spending restraint, rather than the decade of spending increases that preceded the coalition. Services will find it extremely difficult to absorb cuts without toppling over.

It is unsurprising that the Conservative Party, in government for the last 13 years, wants to talk up its own record, but the limited progress to which it can point (the recruitment of 20,000 police officers, increased school spending and progress towards the UK’s 2050 net zero target) is belied by broader data on the appalling state of public services – documented in painful detail in the Institute for Government’s annual Performance Tracker. 4 Produced in association with CIPFA. It also contrasts with the experience of many voters, who are unable to get a GP or NHS dentist appointment, have children who cannot to be taught in RAAC-affected classrooms and whose local libraries and other communities have closed as local authorities struggle to stay afloat.

Meanwhile, there seems to be an unacknowledged inconsistency at the heart of Labour’s policy – between its plans to invest in green industries, improve public services and cut debt – all without raising taxes. This has seen Labour's £28bn green spending pledge placed front and centre of Conservative attacks on "fiscal indiscipline", with Rishi Sunak's party seizing a chance to put pressure on Keir Starmer. The Labour leader recently claimed that if he becomes prime minister the ‘first lever we will pull is the growth lever’. If there was a growth lever that could be pulled so easily, the Conservatives would have done that by now. Re-energising UK productivity after years of stagnation is going to take prolonged, concentrated effort, not a tug on a lever. Paul Johnson, the head of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (and co-presenter along with Anand Menon of UK in a Changing Europe of our new Expert Factor podcast), has said that neither Labour or the Tories are being open about the implausibility of their spending plans when looking at the prospects for the UK economy.

Political campaigns throughout history have been shaped around simple slogans and memorable messages. And politicians have always made selective use of data and evidence to convey the messages they want the public to hear. But the current gap between political rhetoric and reality is dangerous, and not just for the electoral prospects of the governing party. The inconsistency fuels the public’s perception that politicians are dishonest and political campaigns are designed to mislead. According to the 2023 Ipsos Veracity Index, the proportions of people who say they trust politicians and government ministers to tell the truth has fallen to just nine per cent – its lowest level since the survey began in 1983 and lower even than in the aftermath of the 2009 MPs’ expenses scandal. It will do nothing for public trust in government or politics if parties promise lower taxes and better public services, but fail to deliver either.

Politicians need to reflect on the rhetoric they deploy this year in order to win votes, and its potential consequences for voters’ perceptions of politics. It will be in the interests of whoever wins the election for the public to recognise the serious headwinds that will hamper their ability to deliver. Telling the public that trade-offs between tax, spend and public sector debt do not exist is unsustainable even in the medium-term.

Government 2024: IfG's annual conference

2024 will be a crucial year for British politics. To mark the start of this pivotal 12 months, the IfG’s annual conference will bring together influential speakers to explore the key questions facing government.

Register to watch online

Base decisions on evidence

Politics is about debate and disagreement about the direction of the country and about the policies that should be pursued to get it there. What ought not to be in question are the basic data which underpin that debate – regarding the state of the economy, of society or of the environment. In recent years however, some politicians have been too ready to undermine the institutions that their predecessors put in place to establish a common understanding of such facts, and to dismiss the experts or institutions whose job it is to produce and analyse the data.

The assertion of the then justice secretary, Michael Gove, in the run up to the Brexit referendum, that “people in this country have had enough of experts” has become notorious, but there are unfortunately plenty of other examples of politicians willing to downplay the importance of evidence in policy-making and the bodies that produce it. Liz Truss sought to undermine the role of the Office for Budget Responsibility ahead of her disastrous mini-budget and criticised the economic ‘orthodoxy’ of the Treasury. Rishi Sunak has has been willing to undermine one of the UK’s genuinely world-leading bodies – the Committee on Climate Change. And he has pushed ahead with his Rwanda scheme to tackle illegal immigration despite an absence of evidence that it will have a deterrent effect on those willing to risk their lives by crossing the English channel.

Although it may be convenient to try to win political arguments by casting doubt on the authority of key institutions who produce inconvenient facts, this is a recipe for increasing polarisation – as we have seen in numerous countries around the world. It is also a recipe for poor policy, as Liz Truss found to her cost when she attempted to bring forward an extensive package of tax cuts without an authoritative OBR analysis of the impact these would have on the economy.

Our politicians need to start with the evidence when developing the policies they put forward in their manifestos this year, engaging in political debate on their ideas and policy proposals rather than ignoring or contesting the facts.

Strengthen the civil service

Giving greater weight to evidence means strengthening and upholding the institutions that exist to provide it, including the civil service itself. The UK’s public servants have long had a reputation for excellence, but in recent years the civil service has struggled to reform and develop itself while dealing with multiple domestic and international crises. Politicians have been increasingly vocal in criticising the shortcomings they perceive in the work of civil servants, which in turn has had a detrimental effect on morale, increased churn and damaged the ability of the civil service to recruit the next generation of ‘the brightest and the best’.

The Institute’s flagship annual Whitehall Monitor report – published this week – will show that the civil service continues to suffer from deep-rooted and longstanding problems that are undermining government effectiveness. In 2023, staff turnover fell from its post-pandemic peak but remains extremely high and continues to harm institutional memory. Further real terms pay cuts have hindered the civil service’s ability to attract and retain top talent, as have slow and onerous processes for recruiting from outside government. A worrying fall in staff morale has raised questions about how the institution is led. The failure to properly plan the civil service workforce has been exposed by implausible forecast cuts to administration budgets, the prime minister’s U-turn to restore arbitrary targets for headcount cuts, and departments’ increased reliance on private sector consultancies and temporary workers.

These problems are not new. But they are undermining UK government and they represent a decades-long failure to grasp the nettle on civil service reform. Fortunately, support for Whitehall reform seems to be growing, slowly, based on cross-party recognition of the problems, and we look forward to hearing more from the Cabinet Office minister John Glen at our annual conference this week. Civil service reform is unlikely to be a major electoral issue. But it is integral to any government’s ability to tackle the long-term challenges the UK faces.

If they are serious about achieving their political goals, then parties must recognise the importance of giving energy and political weight to government reform. This should include making the centre of government – No.10, the Cabinet Office and the Treasury – stronger and smaller. In February, the Institute’s Commission on the Centre of Government will be publishing proposals for how to do this.

Public services cannot afford another year of short-term headline-grabbing fixes.

2025 will be too late

The next election must be about the ‘how’ of government, not just the ‘what’. And between now and the election, voters should demand that politicians evidence their commitment to more effective government. With the UK teetering on the brink of recession, the country cannot afford not to run its government as efficiently as possible. As long-term systemic problems and demographic trends manifest in ever lengthening waiting lists, degrading infrastructure and workforce shortages, our public services cannot afford another year of short-term headline-grabbing fixes. With public confidence in politics at a low ebb, our democracy cannot afford a year of the personal attacks, trap-setting and scorched earth tactics that we are told will characterise the election campaign.

UK government needs to reform itself, and we cannot wait until 2025 to begin.

- Keywords

- General election Economy Health NHS Schools Public inquiries Public sector Public spending Parliamentary scrutiny Infrastructure The union Official opposition Climate change Immigration

- Political party

- Conservative Labour

- Position

- Prime minister Leader of the opposition

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- Number 10

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak Keir Starmer

- Publisher

- Institute for Government