Five things we learned from the spring budget 2024

IfG experts analyse Wednesday's budget announcement

Jeremy Hunt has delivered his latest budget. Our public finances team offer their reaction to the measures announced, and analyse what the new OBR forecasts that accompanied the chancellor's statement tell us about the state of the UK economy.

1. Has the economic recovery picked up pace?

The OBR has revised its growth forecast for 2024 from 0.7% in its November forecast to 0.8%. This is a slight improvement on 2023, which saw a growth rate of 0.3% over the whole year and a technical recession (two quarters of negative GDP growth) in the final half of the year. The OBR then expects growth of 1.9% in 2025, revised up from 1.4% in its November forecast. A return to growth in the economy, however anaemic, will be a comfort to the prime minister given he made it one of his ‘five pledges’ when taking office (and progress against the others has been a very mixed bag).

The OBR then expects growth to increase slightly in the medium term, averaging 1.8% per year in 2026-28, broadly unchanged from its November forecast (1.9%). In this it remains much more optimistic than the Bank of England about the underlying strength of the economy, and slightly more optimistic than the independent forecasters surveyed by the Treasury in February.

While real GDP is 0.1% higher at the end of the forecast period than expected in November, much of this is driven by an increase in the population forecast, rather than productivity. Real GDP per person, arguably a better measure of underlying economic performance, has fallen in every quarter since the start of 2022. Although it is expected to begin growing again in 2025, the OBR now thinks it will be just under 1% lower by the end of the forecast than was expected in November.

The measures announced at the budget are estimated to increase GDP by 0.3% over the course of the forecast period. There is for example a short-term boost to demand as cuts to national insurance and the fuel duty freeze leave more money in people’s pockets. But, in line with the OBR’s approach to modelling this type of effect, this fades to zero by the end of the forecast period.

More permanent supply-side effects arise from the national insurance cut and changes to the high income child benefit charge, which are expected to increase work incentives. Taken together, these are estimated to raise GDP by 0.2% by the end of the forecast period. The OBR estimates that the measures will increase the size of the workforce by the equivalent of 100,000 full-time workers, which comes on top of an increase of 200,000 due to the combined effects of changes to national insurance, childcare, welfare and other measures announced at the last two fiscal events. This represents an increase of just under 1% in the total size of the workforce, but is partially offset by the effect of freezing income tax thresholds, which reduces the size of the workforce by the equivalent of 130,000 workers.

2. What are the prospects for household finances?

There is some good news for household incomes in the OBR’s new numbers, though only relative to the dire set of forecasts it published in November. Disposable income per person is now expected to increase modestly in real terms in 2024/25, rather than fall further. And it is expected to return to its pre-pandemic peak in 2025/26, rather than 2027/28. Average earnings are also forecast to increase more quickly in real terms this year as inflation falls faster than anticipated a few months ago.

The chancellor’s headline national insurance cut helps to boost post-tax incomes by around 0.5% on average (with the greatest cash benefit going to higher earners). However, other tax rises that had already been announced before today, most notably the freeze to income tax and national insurance thresholds, offset this over the five-year forecast horizon.

Overall, there is little in the numbers to suggest the government will enter the election – expected this year, and to be held no later than January 2025 – with people feeling better off. Even as wages increase in real terms this year, at the time of the election on average households will have real incomes lower than when the parliament began in 2019.

3. Did the new forecast grant the chancellor more flexibility against his fiscal rule?

Jeremy Hunt today strode further through the fiscal looking glass. That he is able to reflects deep flaws in our fiscal framework. The chancellor’s available headroom – the gap between the expected level of debt in the fifth year of the forecast and the level that would breach his rule that debt must fall as a share of GDP – reduced slightly from £13bn in November to £12.2bn today (before policy measures). The balance of tax and spending decisions after today’s announcement reduced that headroom still further, to £8.9bn, leaving Hunt with the second lowest amount of headroom a chancellor has maintained against their fiscal rule since 2010.

But records aside, the concept of headroom itself is pretty much nonsense. It is a figure based on highly uncertain forecasts of debt, half a decade in the future. ‘Fine tuning’ fiscal policy by making incremental tax giveaways based on movements in this number creates unnecessary policy uncertainty and undermines fiscal sustainability – and is something we argued strongly against in our recent report on flaws in the fiscal framework.

Worse, the chancellor is not even likely to meet his fiscal rule, despite his claims to the contrary and the OBR giving him a ‘pass’ in its formal assessment of the government’s performance. That is because the OBR is required to take stated government policy at face value. But this too is a fantasy: overall budgets per person for public services are allegedly going to be frozen in real terms even though the government has committed to large spending increases in specific areas (such as the NHS, defence and overseas aid). Meanwhile, the energy windfall tax is set to expire the year after the forecast period, which would reduce any headroom available to the chancellor in the following years. This fiscal fiction is another problem our report seeks to address.

This game playing is taking place in a context where the UK faces serious fiscal difficulties. Despite a historically high tax burden (even when factoring in today’s cuts), without radical change in fiscal policy it is difficult to construct a plausible path for public spending that is consistent with tackling chronic underperformance across public services – or to meet both parties’ stated desire to at least stabilise, if not reduce, debt as a proportion of the economy. This budget has made no contribution to tackling these challenges. By furthering fiscal fiction, it has, at least at the margin, made them worse.

4. Were spending plans revised, or spelled out?

The chancellor has chosen to broadly maintain spending on public services at the same level announced in the autumn statement. For 2024/25, the only major change is an extra £2.5bn for the NHS in England, roughly what the NHS needs to cover the recurrent costs of higher pay deals for staff agreed last year.

The chancellor will need to hope that his tax cuts provide a political dividend, because the 2024/25 spending plans will provide little in the way of good news from public services. Most are performing worse than on the eve of the pandemic and substantially worse than in 2010, and with budgets set to remain flat or fall over the coming year there is little prospect of substantial performance improvements before the election.

NHS waiting lists are projected to start falling from mid-2024 but are likely to still be higher than before the pandemic at the end of the next parliament, while very little progress has been made reducing the case backlog in the crown court. It is also likely that more local authorities could issue section 114 notices, necessitating further painful cuts to services.

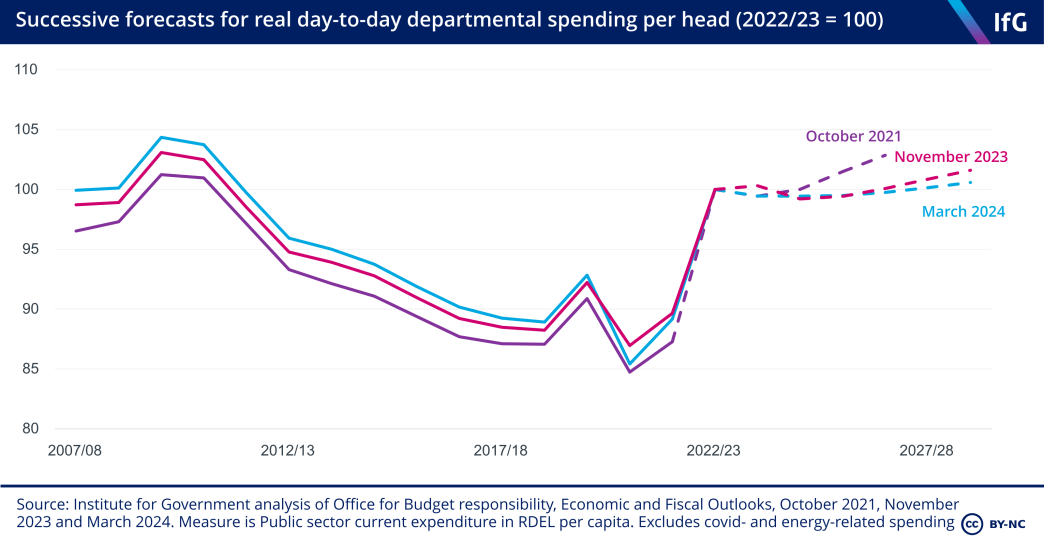

The situation from April 2025 onwards is bleak, with real spending per head on unprotected services set to fall by 3.0% per year, down from 2.5% per year in the November forecast as a result of a higher projected population. The reality is that these spending plans will be impossible to deliver. Over the past year, when spending plans were substantially more generous, the government was still forced to provide emergency top ups such as handing around £4bnto the NHS and providing local authorities with £600m more than planned. It has also raided capital budgets to cover shortfalls in day-to-day spending. In total, the government has made in-year cuts to capital budgets of £3.6bn since November.

The chancellor was absolutely right to talk about the potential for productivity improvements – see our recent event showcasing examples from criminal justice services – and some of the investments could make a big difference. However, the promised £3.5bn investment in NHS technology and digital transformation won’t come until 2025/26 onwards, while the impact of cuts to capital budgets in 2023/24 will be felt much sooner. Productivity improvements will be further hampered by ongoing industrial disputes and continuous policy churn.

The government bequeaths a dismal public services legacy to whoever wins the general election. This budget was never going to undo either the short-term effects of the pandemic or the wider problems caused by poor decisions over decades, but the chancellor has done little to set public services on the path to recovery.

5. What changes did the chancellor make to tax policy?

While Jeremy Hunt made much in his speech of the Conservative Party’s commitment to cutting taxes, the overall picture remains that taxes are set to rise to a post-war high as a result of decisions made by Conservative chancellors over the past 14 years.

Looking at this budget in isolation, it was one in which Hunt announced numerous tax rises (including reforming tax treatment of non-doms, a new tax on vaping products and extending the energy profits levy), many of which will raise a highly uncertain amount of money, to help fund some significant, headline grabbing tax cuts (such as cuts to national insurance contributions or NICs, fuel duty and reforming the high-income child benefit charge) – the revenue costs of which are far more certain.

This budget showcased some common poor practices in tax policy making: most obviously announcing major tax changes without a proper policy development process, including open consultation. The reforms of the non-dom tax regime are something that mere months ago the Treasury was savaging in anonymous media briefings.1 There were some positive developments in that the Treasury did provide a reasonably clear description of what the non-dom reforms are aiming to achieve. But, given the importance of using good evidence in tax policy making, it was frustrating that the documents published by both the Treasury and the OBR are vague about what evidence they have used to cost this policy, even though this is an area that has been examined in detail by external researchers.

One ray of light, in terms of improving the structure of the UK tax system, was that Hunt chose to again focus tax cuts on NICs rather than income tax. This helps to reduce the discrepancy between how earned and unearned income is taxed. However, the public would be better served if the government set out a clear strategy for long-term tax reform, rather than constant tinkering as a result of last-minute political horse-trading.

In a move that will have surprised nobody, Hunt’s other big tax cut was the announcement that fuel duties will be frozen for another year. This will cost of £3bn in 2024/25 but just £800m a year thereafter because – he claimed with a straight face – fuel duties will rise by 5p a litre next March and then be indexed to price growth thereafter. In reality, no chancellor has increased fuel duties at all since January 2011. If the government failed to follow through with future rises, it would have even less headroom against its target to get debt falling in five years’ time: the OBR estimates that about half its £8.9bn headroom would be wiped out under that scenario.

- Topic

- Public finances

- Keywords

- Budget Economy Tax Public spending Public sector Spending review Autumn statement General election Cost of living

- Political party

- Conservative

- Position

- Chancellor of the exchequer

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Jeremy Hunt Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government