Scottish independence

How could a second referendum on Scottish independence happen?

Why are people talking about Scottish independence?

The issue of Scottish independence remains at the centre of political debate in Scotland, eight years after Scotland first voted on this question.

The Scottish electorate rejected independence by a margin of 55% to 45% in a referendum held on 18 September 2014. The independence question then rose back up the agenda as a result of the EU referendum in June 2016, at which 62% of Scottish voters backed Remain.

In its manifesto for the 2016 Scottish parliament elections, which took place shortly before the EU referendum, the SNP had argued that “Scotland being taken out of the EU against our will” would justify a second vote on independence. This has remained a pillar of the SNP argument in favour of a referendum.

The SNP's 2019 UK general election manifesto called for a second referendum to be held in 2020. After winning 48 of Scotland’s 59 seats, Nicola Sturgeon formally requested the power to hold such a referendum, but Boris Johnson refused, arguing that key pro-independence figures had said that the 2014 referendum was a “once in a generation opportunity”, so there was no case for a re-run. 38 Letter from PM Boris Johnson to First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, 14 January 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/857586/Nicola_Sturgeon_20200114.pdf

Scottish independence was again at the centre of debate in the 2021 Scottish parliament election campaign. The election delivered a third successive pro-independence majority. The SNP and Scottish Greens, which both campaigned on a manifesto commitment to a second referendum, won a combined 72 out of 129 seats.

The Scottish government argues that this pro-independence majority provides a “cast-iron mandate” for a second referendum to now take place. 39 Sturgeon N ‘Nicola Sturgeon: Any attempt to block a second referendum would show the UK is no longer a partnership of equals’, Holyrood, 29 August 2021, retrieved 23 September 2021.

The UK government has held to the position that “now is not the time” for a second referendum. 40 Johnson S ‘Theresa May tells Nicola Sturgeon 'now is not the time' for second independence referendum’, The Telegraph, 16 March 2017, retrieved 23 September 2021, www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/16/theresa-may-formally-rejects-nicola-sturgeons-timetable-second; www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-61980405 Secretary of state for Scotland Alister Jack has previously suggested that a referendum should only be held if polls consistently found that 60% of Scots wanted this to happen. 41 Pooran N and Miller D ‘Alister Jack says Scottish independence referendum could happen if polling shows 60% support’, The Scotsman, 27 August 2021, retrieved 23 September 2021, www.scotsman.com/news/politics/alister-jack-says-scottish-independence-referendum-could-happen-if-polling-shows-60-support-3361949

Does the Scottish parliament have the power to hold another independence referendum?

The Scottish parliament cannot hold another independence referendum without consent from the UK government.

The legislative powers of the Scottish parliament are set out in the Scotland Act 1998. This legislation specifies that the Scottish parliament cannot pass legislation that relates to various “reserved” matters including “the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England”. 42 Scotland Act 1998, c.46, s5 The Supreme Court ruled in November 2022 that this means the Scottish government’s proposed independence referendum bill was outside the Scottish parliament’s powers.

In deciding whether the Scottish government could pass the bill, the court assessed whether it would “relate to” the union in terms of its “purpose and effect”. Its judgement stated “it is plain that a bill which makes provision for a referendum on independence – on ending the union – has more than a loose or consequential connection with the union”. 43 Reference by the Lord Advocate of devolution issues under paragraph 34 of Schedule 6 to the Scotland Act 1998, Supreme Court, para 82, https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2022-0098.html

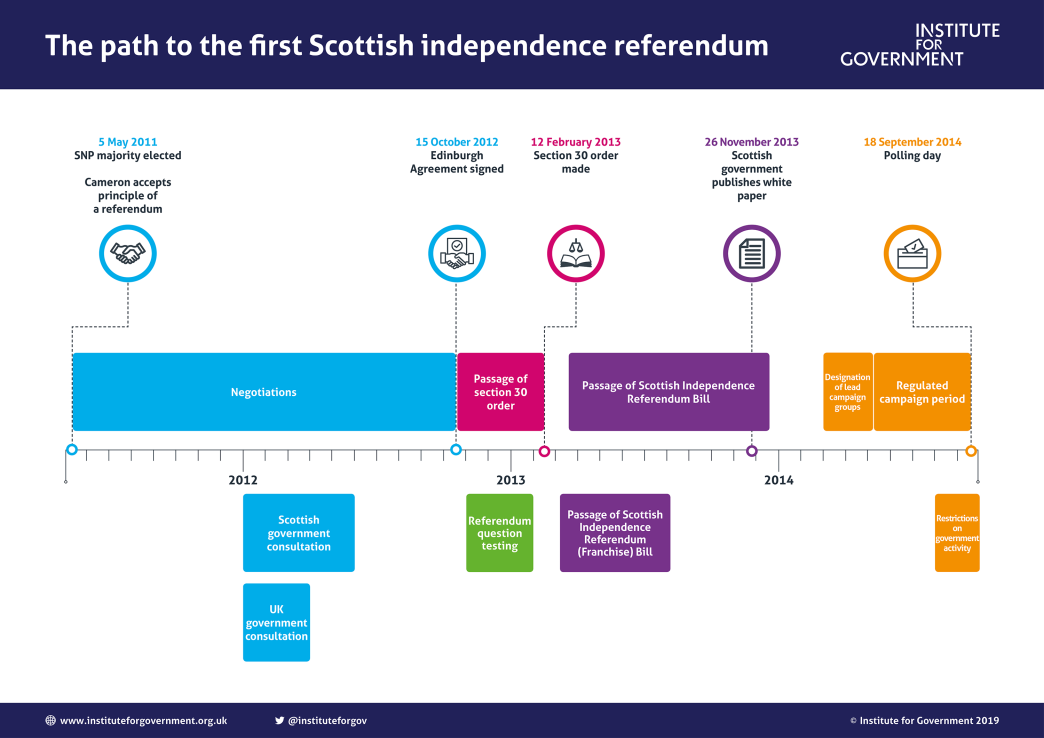

In 2014, the power to hold the first referendum was transferred to the Scottish parliament after agreement on the terms of the vote was reached between the UK and Scottish governments. 44 ‘Agreement between the United Kingdom Government and the Scottish Government on a referendum for independence for Scotland’, 15, October 2012, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/313612/scottish_referendum_agree

Following this agreement, the UK parliament passed a piece of legislation called a ‘section 30 order’ – which gave the Scottish parliament the power to legislate for the referendum. This “put beyond doubt” the legality of the vote.

Importantly, however, the power to hold a referendum was devolved on a temporary basis: the order specified that the vote must take place before 31 December 2014, following which the power expired.

What is the SNP’s plan for a second independence referendum?

In its May 2021 election manifesto, the SNP stated that it would seek to hold a referendum over the course of the parliament, but not until “the Covid crisis has passed”.

Sturgeon presented the SNP’s plans for a second independence referendum to the Scottish parliament in June 2022. She announced she had written to the prime minister requesting a section 30 order. Recognising the UK government was unlikely to agree, she also announced her intention to hold a referendum on 19 October 2022 and asked the Lord Advocate, Scotland’s highest law officer, to seek the Supreme Court’s ruling on whether it would be within devolved legislative competence. 45 Scottish government, ‘Next steps in independence referendum set out’, https://www.gov.scot/news/next-steps-in-independence-referendum-set-out

Following the court’s ruling in November 2022, Sturgeon reiterated her alternative plan of fighting the next UK general election as a “de facto referendum” on Scottish independence.

Her successor Humza Yousaf endorsed the de facto referendum strategy, saying independence would be on “page one, line one” of the next SNP manifesto. There have been divergent views of what that entails. In October 2023, delegates at the SNP conference voted in favour of an amended strategy, that if the SNP win the majority of Scottish seats at the next general election the Scottish government has a mandate to negotiate with the UK government on a referendum or independence. 46 Johnson S, ‘Humza Yousaf changes independence strategy for third time in a year’, The Telegraph, 15 October 2023, www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2023/10/15/humza-yousaf-snp-scottish-independence-strategy/ There is no indication that either the Conservatives or Labour at Westminster would engage in these negotiations.

What rules would govern how an independence referendum would be held?

If a second referendum is held, the Referendums (Scotland) Act 2020 would set the rules for holding the poll, unless otherwise agreed by the Scottish and UK governments. The Act broadly replicates the legal framework for referendums held by the UK government, as set out in the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000.

The Electoral Commission would be given a statutory role, overseeing the conduct of the poll and the regulation of referendum campaigners, including designating lead referendum campaigners and testing the “intelligibility” of the proposed referendum question.

In its referendum bill, the Scottish government proposed using the same referendum question as the 2014 vote: “Should Scotland be an independent country?” with Yes and No options on the ballot paper. 47 Scottish Government, Draft Independence Referendum Bill, 22 March 2021, www.gov.scot/publications/draft-independence-referendum-bill/pages/5; www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-independence-referendum-bill

The Referendums (Scotland) Act 2020 provides that the franchise for any future referendum (on any subject) held by the Scottish government will be the same as the franchise for Scottish parliament elections.

Following the Scottish Elections (Franchise and Representation) Act 2020, this means that anyone aged 16 or over, who is legally resident in Scotland regardless of nationality, and who is on the Scottish local government electoral register, would be entitled to vote.

The 2020 legislation also extended the right to vote to prisoners serving sentences of less than 12 months.

By contrast, the franchise for Westminster parliamentary elections is limited to British, Irish, and certain Commonwealth citizens who are aged 18 or over and living in the UK (or a British citizen who has been living abroad for less than 15 years).

When could a second referendum on Scottish independence take place?

The Scottish government planned to hold a referendum on 19 October 2023. However, this was prevented by the Supreme Court’s judgement. Any future referendum would require agreement between the UK and Scottish governments on its terms and timing.

This means the exact timeline may vary for a second referendum, but the first independence referendum took place three years and four months after the SNP won a majority for independence.

Where do other Scottish parties stand on independence?

Other than the SNP, the pro-independence parties represented in the Scottish parliament are the Scottish Greens and Alba. This means that there is pro-independence majority in the Scottish parliament.

In August 2021, the SNP and the Scottish Greens announced a cooperation agreement. This agreement included a joint commitment to securing “Scotland’s future as an independent nation in its own right.” 48 ‘Draft cooperation agreement between the Scottish Government and the Scottish Green Party Parliamentary Group’, 25 August 2021, www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-and-scottish-green-party-cooperation-agreement/. However, in April 2024 First Minister Humza Yousaf ended the agreement.

In their 2021 Scottish election manifestos, the Scottish Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat parties all reiterated their opposition to a second independence referendum.

Does the Scottish public support independence?

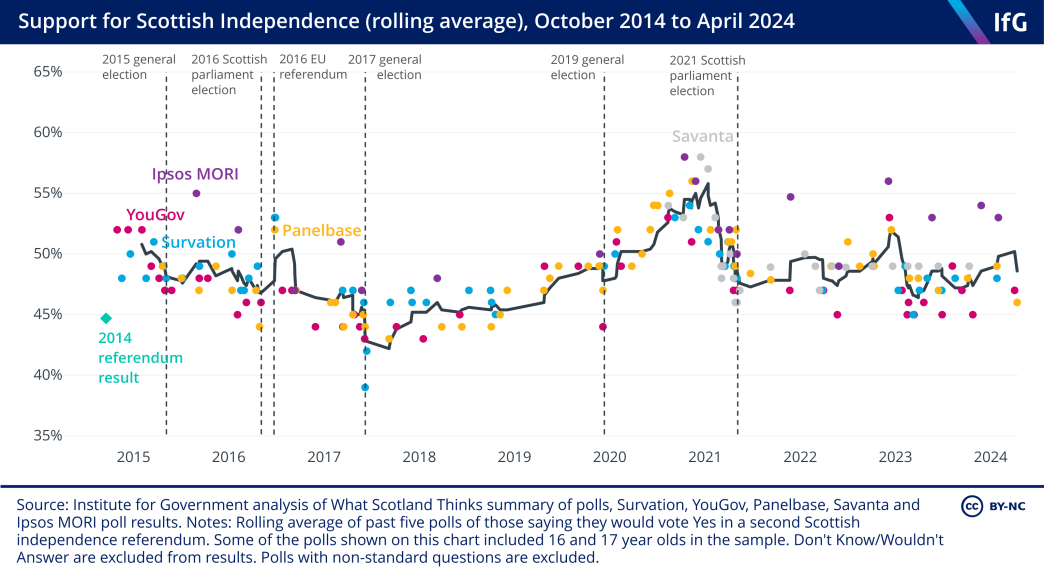

Opinion poll data shows that Scotland is almost evenly divided on the question of independence, with No narrowly ahead of Yes in most recent polls.

Support for independence has fluctuated over recent years, without either Yes or No ever establishing a decisive lead in the polls. Support for independence was at its highest in 2020 but fell back below 50% prior to the May 2021 Scottish parliament election.

Most polls have replicated the Yes/No question asked in 2014. However, some polls use a Remain/Leave question similar to the one asked in the EU referendum and these have typically shown lower support for independence.

If Scotland voted Yes to independence, what would happen next?

A Yes vote in a referendum accepted as legitimate by both sides would be followed by negotiations between the UK and Scottish governments on the terms of separation, including on how to divide the assets and liabilities of the UK state and on the future relationship between the two new countries.

The SNP plan is for an independent Scotland to re-join the EU. As the UK has already left the EU, an independent Scotland would need to apply to join under Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union after first completing its separation from the rest of the UK. Re-entry would require accession negotiations and the consent of all 27 EU member states.

An independent Scotland would also have to decide which currency to use. In May 2018, the SNP Sustainable Growth Commission recommended that an independent Scotland should continue to use Sterling (without a formal monetary union) for a “possibly extended” transition period before introducing its own currency. 51 The Sustainable Growth Commission, The Monetary Policy and Financial Regulation Framework for an Independent Scotland, May 2018, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5afc0bbbf79392ced8b73dbf/t/5b06e8a56d2a73f9e0305ad9/1527179438303/SGC+Part+C+Currency+Mon However, in 2019, SNP party conference voted to replace Sterling with a new Scottish currency “as soon as is practicable.”

Retaining the pound would minimise disruption to trade between Scotland and the rest of the UK, but Scotland would be left without control of its own monetary policy, meaning it could not set interest rates or use quantitative easing to respond to economic shocks.

As a member of the EU, Scottish trade with the rest of the UK would be governed by the same rules as apply to trade between Great Britain and the EU. This would create new barriers to trade across the Anglo-Scottish border.

An independent Scotland would also face difficult choices about spending priorities. Analysis by the Scottish government published in August 2022 found that Scotland’s notional government deficit stood at 12% of GDP in 2021/22. 52 Scottish Government, Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS), 2021-22, August 2022, https://www.gov.scot/publications/government-expenditure-revenue-scotland-gers-2021-22 That meant that public spending per person in Scotland was around £4,300 higher than tax revenue per person.

- Topic

- Devolution

- Public figures

- Nicola Sturgeon

- Publisher

- Institute for Government