Three reshuffle questions for the prime minister

Tim Durrant sets out the questions Boris Johnson should be asking as he weighs up his options for a ministerial reshuffle

The departure of senior aides from No10 has led to rumours that the prime minister is planning a ministerial reshuffle. Tim Durrant sets out the questions Boris Johnson should be asking as he weighs up his options

As Boris Johnson reshuffles his No10 after the departures of Dominic Cummings and Lee Cain, it has been rumoured that a reshuffle of his ministerial team may follow.

Johnson may want a reshuffle to reset the narrative after a difficult few months, to shore up political support or to remove ministers who have been struggling during the pandemic. The threat of a reshuffle is also a useful way to keep his cabinet in line while he steadies the ship. But it is essential that the prime minister thinks beyond the short term headlines and pressures of party management. Here are three questions Boris Johnson should consider before inviting ministers to Downing Street.

1. Does the prime minister want his ministers to gain more experience?

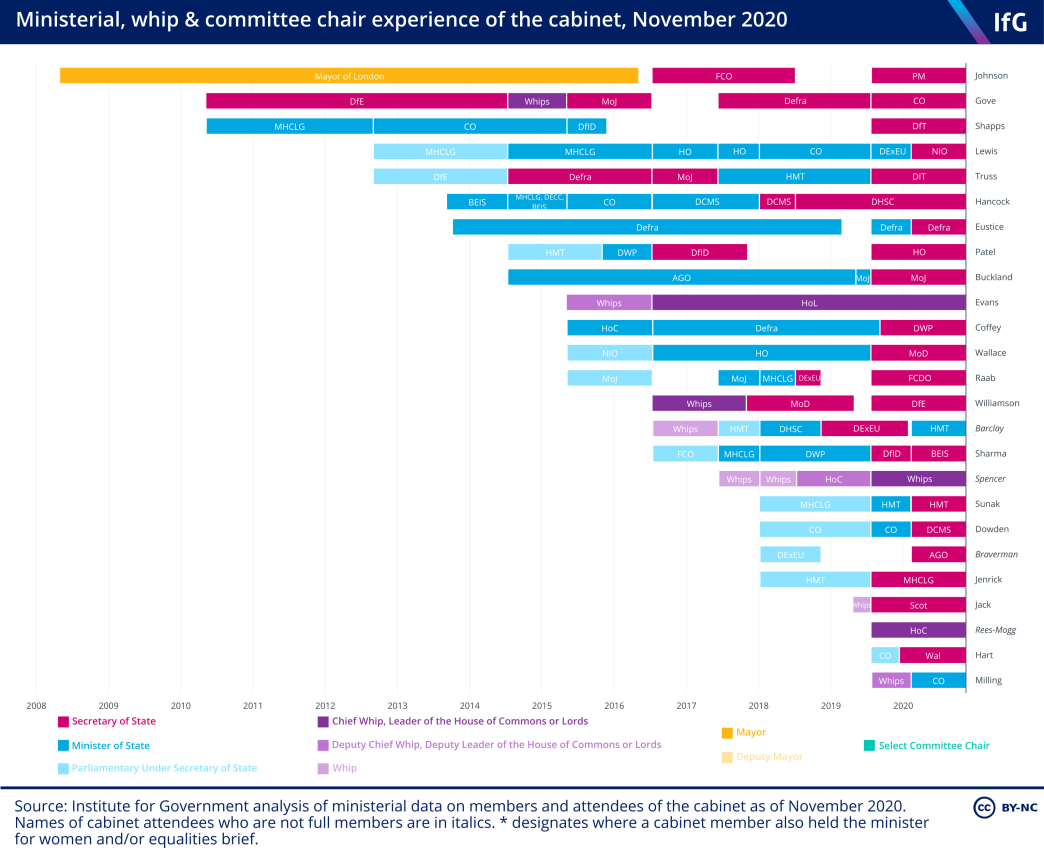

When Johnson became prime minister, he made sweeping changes to the cabinet, getting rid of most of the ministers who had been in Theresa May’s top team. This was followed by a smaller, but still dramatic, reshuffle in February, just before the pandemic really hit the UK. As a result, apart from a few notable exceptions, none of Johnson’s ministers have spent a long time in their posts. Michael Gove and Liz Truss are the longest-serving Cabinet ministers, but they have moved departments frequently.

Only Defra secretary George Eustice, health secretary Matt Hancock and Robert Buckland, the justice secretary, have served more than 18 months in a role relevant to the department they now lead. Eustice served as a junior Defra minister for over five years before becoming secretary of state, Buckland was one of the government’s senior legal advisers before becoming justice secretary and Hancock has been in post at DHSC since the summer of 2018.

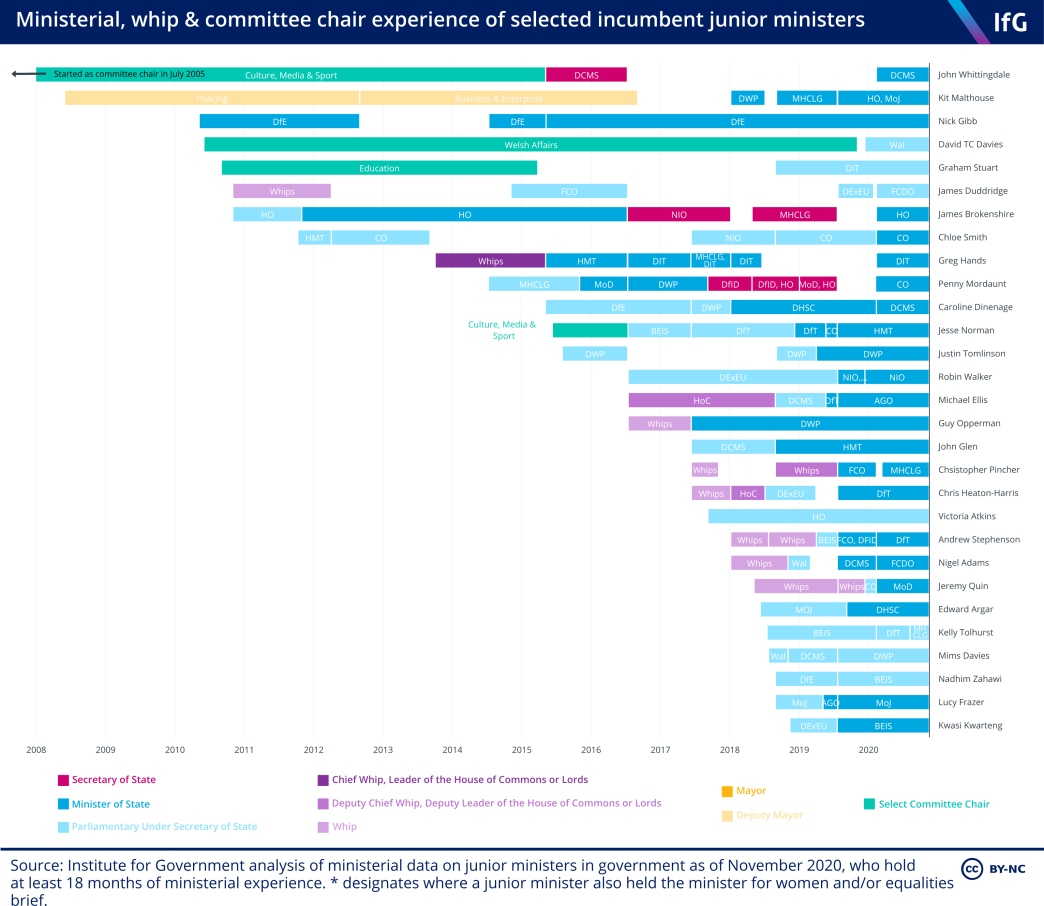

The situation is similar in the junior ranks of the government, where the majority of ministers have been in their post for under two years. Only a handful of exceptions – notably Nick Gibb, who has been at the Department for Education since 2014 – have been in their current role for longer.

IfG research shows the value of allowing ministers to remain in one post for an extended period time. Frequent job moves means minsters are unable to gain experience and see policies through, while Parliament finds it hard to hold ministers to account. Coupled with high turnover among officials this also means departments suffer constant changes in direction, undermining attempts to bring in long-term reform and creating confusion and waste. Under-performing ministers should not be kept on, and impressive junior ministers should be considered for promotion, but stability is valuable – ministers should not be moved unless there is good reason.

2. Does Boris Johnson want to have a wider range of views in the cabinet?

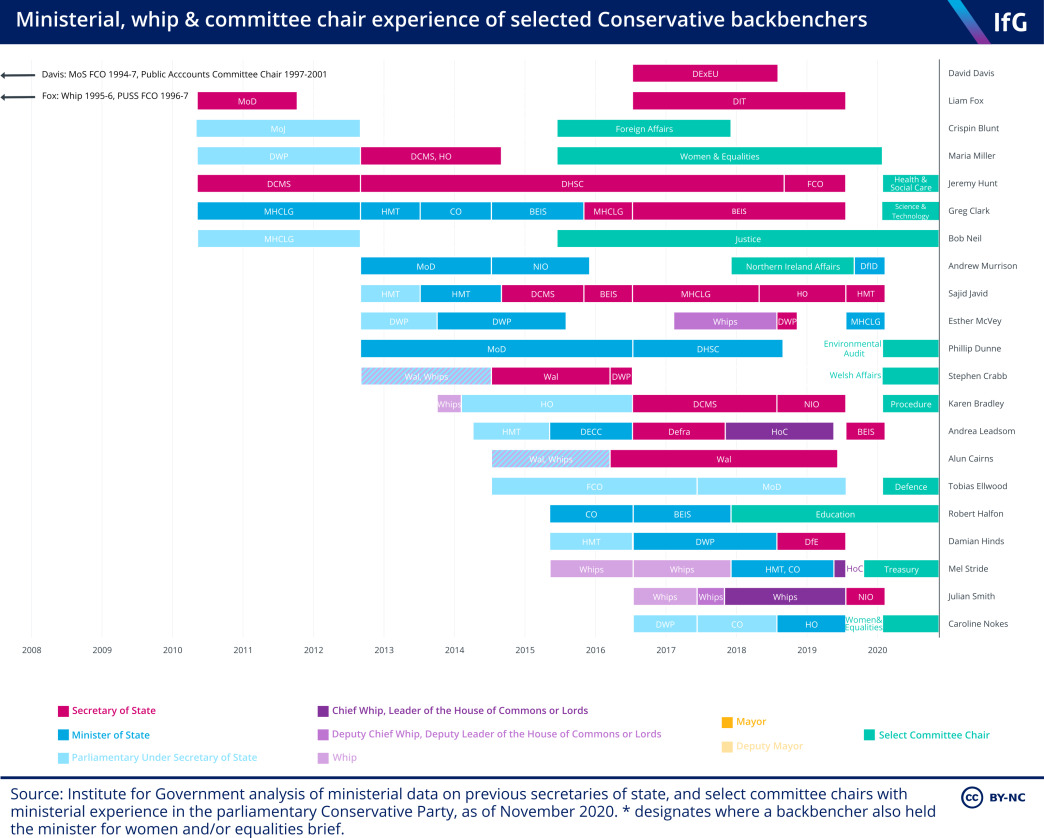

After over a decade in government, the Conservative parliamentary party has accumulated a lot of ministerial experience in its ranks, but Johnson's first Cabinet, picked in July 2019, was chosen largely on ministerial loyalty to his vision of ‘getting Brexit done’.

However, the UK has now left the EU, key Vote Leave advisers have left Downing Street and the transition period is nearly over. By selecting his team from a wider pool, and recognising talent rather than rewarding loyalty to the Brexit cause, the prime minister can bring a broader range of views into the government and around the cabinet table, helping improve the quality of decision-making.

The change of advisers in No10 may affect who wants to be a part of Johnson's ministerial team. Some ex-ministers, such as former chancellor Sajid Javid, who quit in February rather than accept the imposition of a new team of special advisers from No10, may consider returning if asked. Others may prefer to remain on select committees or as backbenchers.

3. Is the middle of a crisis the right time to reshuffle?

The government is heralding a ‘reset’ of its agenda with big announcements on climate change and defence, and a reshuffle may form part of the reset narrative. But, right now, it would also be a risk, with the UK approaching the end of the Brexit transition period and the pandemic far from over.

Despite having less experience of governing than many of their backbench peers, this is a cabinet with specific experience of being in government during the Covid-19 crisis and in preparing for the post-transition period. In a period of intense pressure, a new team would need to get up to speed on the decisions and priorities of their predecessors. Johnson must weigh up where a change might improve a department's performance in the long term, or risk short term set backs. New faces at the cabinet table may bring fresh energy, ideas and approaches into the government, but with reshuffles so often going wrong, and the prime mininster under pressure to get his premiership back on track, Johnson must be certain to get his appointments right – and make them for the right reasons.

Data analysis and visualisation by Ketaki Zodgekar

- Supporting document

- government-reshuffles.pdf (PDF, 1.11 MB)

- Topic

- Ministers

- Keywords

- Government reshuffle Cabinet

- Position

- Prime minister

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Public figures

- Boris Johnson

- Publisher

- Institute for Government